Update: Finds or Fakes?

054

Digging Deeper

There is a saying in archaeology: The answer lies below. The corollary to this is: Dig deeper.

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) is indeed digging deeper. But not as an archaeologist would in an effort to find the answer to a problem. It is digging itself deeper into a hole.

The whole world wants to know whether the inscription on the James bone box—“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”—is authentic or a forgery. The IAA is doing everything it can to prevent this from being scientifically determined. Why? Because it is absolutely convinced that the inscription is a forgery—or at least part of it is a forgery (which part is unclear.)

The IAA’s first mistake was not to allow scholars and scientists freely to explore the issue and—if differences occurred—to allow differing viewpoints and insights to be openly debated. Instead, the IAA and its strongheaded director Shuka Dorfman appointed a committee to act as a judge—to make a final decision, like a court.

The IAA’s next mistake was to pretend the committee’s decision was unanimous when there were clearly differences within the committee. One committee member said he would find the inscription authentic based on his own expertise, but the analysis of the two geologists on the committee “forced” him to change his mind. That is, he was deciding the matter not on the basis of his own expertise, but on the basis of what expert geologists told him. Another member of the committee found evidence that the last two words—“brother of Jesus”—had ancient patina in the letters, showing they were authentic. Moreover, most members of the committee did not vote based on their own expertise but on the analysis of the two geologists—which has been widely criticized as “deeply flawed.”

To make matters worse, the IAA would not make the bone box (or ossuary, to use the technical term) available to other scholars and scientists to allow an open discussion.

Determined to defend its position at all costs, the IAA next had the police investigate the matter and charge the owner of the ossuary with forgery. The criminal indictment charges five men with a forgery conspiracy. But only the owner of the ossuary—an Israeli antiquities collector named Oded Golan—is charged in connection with the James ossuary. He apparently did it alone (according to the IAA).

Why is this digging deeper? Because by filing a criminal indictment, the IAA has undertaken to determine the question by the highest and most stringent level of proof. The IAA must prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the inscription—or part of it, at least—is a forgery. If there is a reasonable doubt as to whether the inscription is a forgery, the Israeli court must acquit.

On the face of it, there is clearly a reasonable doubt. André Lemaire, the Sorbonne epigrapher who initially analyzed the inscription, continues to maintain it is authentic. So does Ada Yardeni, one of Israel’s leading paleographers. Emile Puech, of the French Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem, says the inscription is clearly of one hand, contradicting the indictment’s charge that only the last two words of the inscription are forgeries. Orna Cohen of the IAA committee has said she saw ancient patina in the last two words of the inscription. Another member of the IAA committee, Ronny Reich, who said he was “forced” by the geologists’ analysis to vote that it was a forgery, has now changed his mind, telling an American audience that he now thinks the inscription is authentic (although not archaeologically important). The geologists from the Israel Geological Survey who initially found the inscription authentic from the geological viewpoint continue to maintain their position, in opposition to the IAA committee’s geologists. So does the scientist who examined the ossuary and its inscription for the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto when the ossuary was exhibited there.

If this doesn’t establish a reasonable doubt, I don’t know what would.

But an acquittal will not settle the question. That is why it is so foolish to bring a criminal indictment in the face of clear evidence raising a reasonable doubt.

If there is an acquittal based on a reasonable doubt, the world will still want to know if the inscription is a forgery. And the only way this will be established is to allow experts of all kinds to examine the ossuary. They should be encouraged, not barred. Their judgments should be elicited, not disdained.

The only answer I was able to get in defense of the IAA and its strategy on a recent visit to Jerusalem is that the IAA thinks it has irrefutable, though still secret, evidence proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the inscription—or at least part of it—is a forgery. Perhaps so. There is talk of an Egyptian jeweler whom Israeli investigators interviewed in Egypt, despite the absence of permission from the Egyptian authorities. Maybe he confessed. Maybe this will establish the case beyond a reasonable doubt. Whether he can be brought to Israel is another question. Whether his evidence was given freely may be still another question.

In any event, in the absence of conclusive evidence that the inscription—or at least part of it—is a forgery, the IAA is simply digging itself into a deeper hole, postponing the day, perhaps for years, when scholars and scientists can freely examine the inscription to determine whether it is authentic or a modern forgery. In the meantime, we must all wait.

If the defendant is acquitted of forging the ossuary inscription, the IAA will finally have to answer for this flawed strategy.

For a more detailed analysis of the indictment, see “Weak Case”.

055

Is the New Royal Moabite Inscription a Forgery?

A few years ago an inscription on stone purportedly by a Moabite monarch appeared on the antiquities market in Israel. It was purchased by American collectors Michael and Judy Steinhardt, reportedly for $350,000. They then lent it on a long-term basis to the Israel Museum, which at the end of last year admitted that an inscribed ivory pomegranate in its collection, for which it had paid $550,000, was a forgery.a Neither the American collectors nor the museum has any idea where the inscribed Moabite inscription came from. In the jargon of the trade, it is unprovenanced. Is the inscription authentic or is it a modern forgery on an ancient stone?

A scholarly analysis of this royal Moabite inscription was published in Israel Museum Studies in Archaeology (volume 2, 2003) by Professor Shmuel Ahituv of Ben-Gurion University. Whether the inscription is authentic or a modern forgery was neither considered nor discussed in the publication. According to a report of Duke University professor Eric Meyers, 30 to 40 percent of the inscriptions in the Israel Museum are estimated to be forgeries.

Under the rules of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), this inscription could not be published in any ASOR journal nor presented at its meetings because it came from the antiquities market; the rule is based on the belief that the inscription’s publication or presentation would encourage looting. Under the ASOR rules an unprovenanced object is to be ignored for scholarly purposes. Neither could this royal Moabite inscription be displayed in the British Museum, which under the tutelage of Lord Colin Renfrew, will no longer acquire or display artifacts from the market.

This situation reflects the deep divide in the scholarly world as to what to do with objects that come to light via the antiquities market. In Israel it is a kind of schizophrenia: Some, like the Israel Antiquities Authority, would like to make it illegal to trade in antiquities. Others, as reflected in their willingness to publish inscriptions from the antiquities market, take a different view.

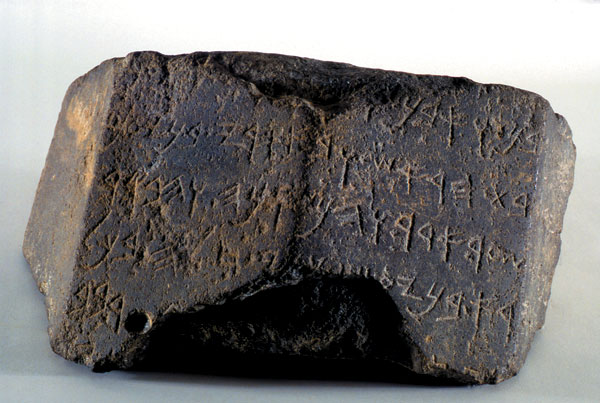

The new royal Moabite inscription is inscribed on an eight-sided column drum made of black basalt. It had apparently been reused in a wall, as shown by mortar on the bottom and the fact that the upper portion of the drum was reworked to fit into the wall. Only five of the facets of the octagonal drum have survived, and only three of these are complete. A complete facet is about 5.5 inches wide. The drum itself weighs almost 50 pounds. The seven-line inscription is on three facets, except for one letter on a partial fourth.

Palaeography (the study of ancient scripts) identifies the inscription as Moabite; some of the letters are shaped like typical Moabite letters. It is royal because, in typical ancient fashion, the “I” of the inscription boasts of what he built. He also brags about his exploits in a war with the Ammonites, whose kingdom bordered ancient Moab. He took many “Ammonite captives” and weakened them in “every [way].”

On paleographic grounds, Professor Ahituv dates the inscription to the 056mid-eighth century B.C.E. or perhaps a little later.

The complete inscription, in Professor Ahituv’s translation, is in the box at page 55.

According to principles of extreme skepticism recently proposed by American paleographers Andrew Vaughn of Gustavus Adolphus College and Christopher Rollston of Emanuel College of Religion, the new royal Moabite inscription has all the hallmarks of a recent forgery. First, it violates the TGtBT rule (To Good to Be True) championed by Professor Vaughn.

In addition, the inscription displays several other features that, under the recent rules of extreme skepticism, would arouse heightened suspicion. One is the absence of the Moabite king’s name. This is a common feature of inscriptions recently found to be forgeries. For example, in the Israel Museum’s inscribed ivory pomegranate, at first thought to be the only relic from Solomon’s Temple, the name of the Israelite deity Yahweh is missing; only the final “h” is there, requiring scholars to reconstruct the name Yahweh. The final “h” leaves open the possibility that the destroyed name was Asherah, a pagan deity whose name ends in the same letter.

A similar situation prevails in the now-famous Jehoash (or Yehoash) inscription.b The name of this Judahite king is not in the inscription. The first line of the inscription has been destroyed, leaving scholars to infer the name of the king from the rest of the inscription.

Another suspicious thing about the new Moabite inscription: In ancient inscriptions from this period, when there is not enough room for an entire word at the end of a line, it is customary for the engraver to start the word and then continue it at the beginning of the next line. Here, however, as Ahituv himself noted, “Not one word of the entire inscription is broken, running over to the following line. Instead, all lines end with a complete word.” Did a forger not know the ancient custom of simply continuing a word on the following line? Was this a forger’s fatal mistake regarding this inscription?

Many of the recently identified alleged forgeries—the James ossuary inscription, the ivory pomegranate inscription, the Jehoash inscription, etc.—are inscribed on genuinely old objects. So is this royal Moabite inscription.

Another inscription of a Moabite king is the famous Mesha Stele (also called the Moabite stone), found in the 19th century by Bedouin.c Professor Ahituv uses the Mesha Stele to help him interpret almost every aspect of this object—from the original height of the column of which the drum was a part (“I presume that the original height of the column was ca. 1.50 m, not unlike the Mesha Stele”) to the content (“Royal inscriptions generally open with the names of the king, his father and his title, as in the Mesha monuments from Dibon and al-Karak”) to linguistics (“… compare [a feminine marker to] the Mesha Stele (line 2)”) to proposed reconstructions (“… following the Mesha Stele, lines 30–31”). And of course Moabite paleography, largely from the Mesha Stele, enables Professor Ahituv to identify the inscription as Moabite. Should all of this alert us to a possible forgery? Is the new inscription just too close to the Mesha Stele? Scholarly readers will recall that soon after the Mesha Stele was discovered a number of imitative forgeries appeared on the market.

Is it time to call in Tel Aviv University petrologist Yuval Goren, who has unmasked all the recent alleged forgeries in Israel—the James ossuary inscription mentioning Jesus, the ivory pomegranate inscription, the Jehoash inscription, etc.—creating what one prominent American paleographer has called “a forgery hysteria” in Israel?

055

Translation

1. [and] I built

2. [and I took] many captives. And I built [the citadel of the royal-house].

3. [And I bui]lt Beth-hora’sh. And with the captives of the Ammonites.

4. [I built for the] reservoir a mighty/strong gate, and the small cattle and the cattle

5. [I carried] there. And the Ammonites saw that they were weakened in every

6. (Only partial letters remain on the sixth and seventh lines).

056

Defending the Study of Unprovenanced Artifacts

An Interview with Othmar Keel

Professor Othmar Keel is a Biblical scholar and a historian of religion recently retired from Fribourg University, Switzerland. Among his many current projects is the creation of a Swiss museum on the Bible and the Orient. “Switzerland is a small country,” he told BAR, “and we have over 900 museums. But not a single one is devoted to the Bible and the ancient Near East. It is a shame we don’t have such a museum.”

Professor Keel is widely known and admired in the scholarly world as the author of Symbolism of the Biblical World (Zurich, 1972; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), which, he reminded us, is still in print after its original publication 057more than 30 years ago and has recently been translated into Spanish. A more recent pictorial collection (with Christoph Uehlinger), Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998), is a magisterial work well on its way to becoming a classic.

BAR: I noticed in your studies that you rely at times on unprovenanced objects that have come from the antiquities market. In light of the forgery accusations that are now being made in Israel, would you continue to do that?

OK: Yes, I will surely continue. Of course one has to be careful, particularly with high-priced items. But with ordinary material, I think it’s no problem. I don’t think we can write a history of the ancient Near East without relying on unprovenanced material. Of course the main material is professionally excavated. But it happens again and again: Important material turns up without a known provenance. There are some very famous examples. What would we do without the [Egyptian] Execration texts with respect to the Levant in the first half of second millennium [B.C.]? What would we do without the Amarna tablets? What would we do without the Qumran [Dead Sea] Scrolls? They’re all from the market.

I deal mainly with seals. Ten times as many seals come from the market as come from legal excavations. Look at the corpus of Hebrew seals published in 1997 by Nahman Avigad and my good friend Benjamin Sass [Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals]. About 10 percent are from legal excavations. The rest are from the market. Sass has quite a strict attitude against things that come from the market, but when he had the chance to publish the complete Avigad seal corpus, suddenly he found himself dealing with a lot of unprovenanced material.

BAR: How do you account for the fact that there are ten times as many unprovenanced items in the corpus as those that have been found in legal excavations?

OK: Why? It is like this: A poor fellow finds on his plot of land a little cemetery. He digs only on his own land. It’s not that someone just goes and digs. You find it on your own land. That’s why these people have the feeling that it belongs to them—because they found it on their land. They dug it. Of course they dig much faster than archaeologists because they don’t care about stratigraphy and other important evidence that doesn’t mean money for them; they are looking for pots or seals or figurines. When they find it, they bring it on the market. There are many more of these people than there are archaeologists excavating.

Sometimes it is just found on the surface. I’ve met many people who go searching on the surface next to a tell, looking for material washed down by the rain, sometimes next to a kibbutz, for example. Some kibbutizim even have a little museum of their finds and they often have quite interesting collections. If you look for surface finds systematically, you can find quite a lot of material.

BAR: What about the people who go out at night with shovels and loot illegally on other people’s land?

OK: I don’t think that this happens very often, because, you know, everywhere in the world people care about their own land and they are not willing to let just any people work on their land. Even among the Bedouin, I don’t think that there is a lot of looting by people coming from somewhere. Yes, sometimes people are employed to go out and find something. I have heard that happens. It is, of course, highly immoral. These people should be prosecuted and brought to court. It is completely illegal.

Of course it’s also illegal when people dig on their own land. They should hand over to the government what they find, but these people are in such a miserable economic situation, you can hardly convince them to do it unless the state is willing to pay them for it.

BAR: What you say seems to conflict with the policy of ASOR (American Schools of Oriental Research). ASOR will not allow an unprovenanced object to be published in its journal or to be the subject of a paper at its meetings.

OK: Yes, surely my view conflicts with ASOR’s policy. I think this policy is a particular kind of American Puritanism. It is a kind of Puritan attitude. Many, many Biblical texts can be understood better in the context of the time they were written when you look at pictorial evidence—and much of this comes from the market.

BAR: What about the forgery problem?

OK: Nowadays people are more skeptical than before, but you must bring arguments to support your skepticism. Of course you can start with the view that everything coming from the market is a forgery and that one has to prove that it is genuine. Or you can look at it as if it is genuine and that you have to prove that it is a forgery. It depends almost on where you start from—belief or skepticism. You can distrust everything and everybody. But I don’t consider this a justified scholarly attitude. You find this attitude in people with very little experience. They mistrust everything that they don’t know about. A true scholarly attitude compares and brings arguments to bear.

BAR: If you were to publish a revised edition of your book, what would you do with the inscription on the ivory pomegranate in the Israel Museum that has just been declared a forgery?

OK: I would say that the inscription on the pomegranate is at the moment a matter of scholarly debate as to whether it’s genuine or not.

BAR: You would still refer to it?

OK: I think so. This kind of primitive distrust toward everything is not scholarly at all.

BAR: Field archaeologists who are opposed to unprovenanced finds often have no need for this material. That’s different from you.

OK: Yes, of course. They are satisfied with what they find in their own excavations. This is natural and understandable: The most important thing for them is what they find. I don’t blame them, but I can’t share their attitude. As a historian of religion and I try to take into account all the material available. These people who are so opposed to the market, their attitude doesn’t relate to reality.

058

New Book Blasts Handling of Antiquities Case

A French investigative reporter has just published a book regarding the inquiry into the James ossuary inscription and other inscriptions alleged to be forgeries by the Israel Antiquities Authority.1 The IAA inquiry has led to a criminal indictment against a leading Israeli collector, a leading Israeli antiquities dealer, a leading Israeli antiquities restorer and two others. Here are excerpts from the book, translated from the French:

“From the beginning of the inquiry, the rumors and allegations coming from Amir Ganor [head of the Israel Antiquities Authority fraud squad], Uzi Dahari [deputy director of the IAA], Yoni Pagis [head of the Israeli police investigation] and Yuval Goren [the Tel Aviv University petrologist who claims his scientific analyses establish that the artifacts in question are forgeries] and all others controlled by the IAA made me, in retrospect, doubt their statements were well-founded. The [report of their] inquiries told a number of lies and half-truths. They also falsified certain facts.”

“This raises questions about the independence of the IAA experts regarding the ossuary.”

“After a two-year inquiry, from the number of dead-end trails, rumors and insinuations, it seems clear that this new affair is a pretext to destroy the Israeli antiquities market as a way of preventing archaeological looting.”

“[As] a consequence, academics who study antiquities from the market suffer opprobrium in the academy, which will discourage young epigraphers and archaeologists from publishing unprovenanced artifacts.”

Why I Think the Prosecution’s Case Is Weak

People who know that many years ago I practiced law and even worked for the U.S. Department of Justice sometimes ask me what I think of Israel’s criminal case charging Oded Golan with forging the James ossuary inscription.

My answer is: Weak. Here’s why:

There are many uncertainties in this case, as in every case. But of one thing, I am sure: If Oded Golan, the owner of the ossuary, is guilty, he had many accomplices. In short, it has to be a conspiracy.

Someone must have sold him the ossuary authentically inscribed, as the indictment admits, “James, the son of Joseph.” Someone must have told him that the Aramaic Ya’acov (Jacob) is translated James as applied to New Testament figures (although it is translated Jacob in English translations of the Hebrew Bible). Someone must have had the idea to add “brother of Jesus” to the inscription that was already there. This spells a scholar who knew the New Testament. It would also take someone who knows Aramaic very well, because there is a rare, difficult Aramaic locution for “brother.” You also need someone who is an expert in paleography—who knows the shape of each of the Aramaic letters in 62 A.D., when James was martyred. And you need someone to do the actual engraving that the expert paleographer identifies for him; the engraver, too, must be an expert because if he makes a mistake, he can’t just start over; if he makes a mistake, he will destroy a very valuable ossuary already inscribed “James, son of Joseph.”

There are probably some specialties I have left out. But this is enough. This has to be a conspiracy of at least a half-dozen people.

From the prosecutor’s viewpoint this is great: The distinguished American judge Learned Hand called conspiracy “the darling of the prosecutor’s nursery.” The larger the conspiracy the more difficult it is to hold together. Somebody’s going to break. Somebody’s going to rat, especially when the prosecutor offers leniency to the first guy to squeal and threatens a great big sentence in the pokey if he’s the second or third guy to spill the beans; then, a prosecutor emphasizes, it will be too late.

059

This is elementary prosecutorial technique. Every prosecutor knows this.

Yet the Israeli prosecutor apparently doesn’t know anyone in the conspiracy—except Oded Golan. The prosecutor tried to break Golan, to get a confession, but was unsuccessful: Golan was shackled in front of his parents and taken in chains to the police station for questioning. He was team-interrogated for 30 hours. Finally, he was arrested, imprisoned (and, he says, threatened) with rapists and murderers for four days—then released without charges. The important point is not only that the prosecutor failed to get a confession, but he can’t even identify any of the co-conspirators who must be there if Golan is guilty.

I know the police haven’t identified any co-conspirators because in the count of the indictment alleging forgery of the last part of the ossuary inscription, Oded Golan is the only one named. There’s no one else from which to try to get a confession. If there were, he would be named in the indictment. In other counts, several defendants are named—but not in connection with the ossuary. Why is Golan the only one named in that count? The best guess is that the prosecution has been unable to find anyone else in the conspiracy.

Why hasn’t the prosecutor been able to identify even one of the co-conspirators? After all, this is Israel. These are people who are able to stop about 80 percent of the terrorists who try to come into the country and blow up innocent people. They know how conspiracies work and they know how to penetrate them. These guys know just about everything—if it’s there.

Another weakness in the case is that it is by no means clear that any part of the ossuary inscription is forged. After all, if you’re going to prove a conspiracy to forge an ancient inscription, you have to prove, first of all, that it is forged. But here, you have some pretty distinguished paleographers who say that this inscription is authentic, people like André Lemaire of the Sorbonne and Ada Yardeni, generally considered Israel’s second-most-distinguished paleographer. You have Emile Puech, a Dead Sea Scroll scholar and expert paleographer, who is sure that just one person inscribed this inscription. If so, it is impossible for the first part to be authentic while the last part is a forgery by a second hand, as the indictment charges.

On the other side, no experienced paleographer has concluded on paleographic grounds that any part of the inscription is a forgery.

Yes, Tel Aviv University petrologist Yuval Goren and his colleague Avner Ayalon of the Israel Geological Survey say their scientific tests prove the inscription is a forgery. But those tests apply to the whole inscription, so they must be wrong if, as the indictment admits, the first part of the inscription is authentic.

But it’s worse than that. Even if Goren’s view is admissible (which it probably isn’t because it conflicts with the indictment’s admission that the first part of the inscription is authentic), it is a widely opposed view. No other scientist has stood up to support Goren’s analysis of the ossuary inscription. And he is opposed by two other geologists from the Israel Geological Survey: Amnon Rosenfeld and Shimon Ilani. Goren is also opposed by Edward Keall of the Royal Ontario Museum, who examined the ossuary when it was exhibited there. All these people not only have examined the ossuary, but they have reflected on Goren’s reasoning and found it thoroughly unconvincing. They continue to maintain the inscription is authentic. James A. Harrell, of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones In Antiquity, also finds Goren’s work deeply flawed.

So the most you can say is that there is a difference of opinion among scientists. This is hardly enough to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the end of the inscription is a forgery.

And this is only a quick review of the evidence. There is other exonerating evidence that is likely further to undermine the prosecution’s case.

Another reason I have little confidence in the prosecutor’s case: The indictment appears to reflect sloppy lawyering, which says to me that the prosecution may not have done its homework. For example, in the opening general section of the indictment the prosecution alleges that an inscribed ivory pomegranate is a forgery. Yet nowhere in any of the 18 counts is this pomegranate again mentioned. No defendant is charged with forging the inscription on the pomegranate. Evidence that the pomegranate is forged would be inadmissible at the trial. Why is that allegation in the indictment? Was there once a draft with a count relating to the forged pomegranate inscription?

Under Israeli law, the prosecution must give the defendants all of the statements it has from witnesses it intends to rely on at trial. This indictment lists 124 witnesses! Any prosecution that needs 124 witnesses to make its case has got to be weak. But that’s not all. Many of the witnesses listed are, so far as is known, witnesses for the defense. Remember that the defendants have all these statements so they know what the prosecution’s evidence will be. By listing defense witnesses as its own, the prosecution will not be permitted to cross-examine them at trial, a major impediment to any attempt to counter the defense’s evidence.

Moreover, the list of witnesses includes people who say they have never been questioned by the prosecution and know nothing about the case—further evidence, if true, of sloppy lawyering.

Perhaps there’s some evidence we don’t know about, but on the basis of the evidence that has surfaced to date, the prosecution has a very weak case. In my judgment, it may even fall apart before trial.

Caution: I’ve been wrong before.

Trial Delayed

The forgery trial of antiquities collector Oded Golan and four others opened on May 17 but was adjourned until September 4. Defense attorneys said that investigators had provided some of their material only days before. Follow the story on the “Update” section at www.bib-arch.org.

Digging Deeper

There is a saying in archaeology: The answer lies below. The corollary to this is: Dig deeper.

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) is indeed digging deeper. But not as an archaeologist would in an effort to find the answer to a problem. It is digging itself deeper into a hole.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

David Noel Freedman, “Don’t Rush to Judgment,” BAR, March/April 2004.

The Biblical text also mentions a city called Adamah (’DMH) (Genesis 10:19) ruled by King Shinab (Genesis 14:2, 8). It appears to be located in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. It is possible that this is the same place as the city of Adam. Adamah has apparently survived in the Arabic place-name Damiah. A bridge across the Jordan is still known as the Damiyeh Bridge.