Why Leah Gives Birth Before Rachel

060

The biblical stories of barren women highlight the serious problem of childlessness in the ancient world. Infertility meant no child to love, to help with daily work, to provide for you in the afterlife, or to inherit land, money, or goods. Most important, without children there would be no one to replace the current generation. For a woman not to have any children posed a problem, both for herself and her husband. Couples navigated fertility issues in a number of ways, some of which were more reliable than others: prayer, magical practices, adoption, surrogacy, and at times a second wife.

Throughout the ancient Near East, a woman’s womb was considered closed until divinely opened. Fertility was in the hands of the gods. Similarly, the Israelites believed that God was in control of the womb. Texts such as Isaiah 54:1-3 praise God for opening wombs and providing children to the once-barren woman. In the barren women narratives, God opens the woman’s womb at key moments in the story. Sarah was able to conceive only after God made the point that the promised child would come from Abraham’s loins and Sarah’s womb. Rebekah conceives after Isaac prays and beseeches God on her behalf. Hannah conceives after she makes a vow to God.

But what of Rachel? How are we to understand the timing of her first pregnancy?

Rachel desperately desires a child. She cries out to Jacob in anguish, “Give me children or I shall die” (Genesis 30:1).

In light of ancient Near Eastern beliefs about fertility, Jacob’s reply comes as no surprise. He retorts, “Am I in the place of God, who has withheld from you the fruit of the womb?” (Genesis 30:2). Rachel must continue to wait. But why? The key narrative motivation for opening Rachel’s womb is not so obvious.

An answer to this mystery can be found hiding in the strange circumstances surrounding Rachel’s marriage. In brief: Jacob fell in love with Rachel and wished to marry her. He went to her father, Laban, and asked for her hand in marriage. He agreed to work seven years for Rachel (Genesis 29:18). Laban appears to agree when he says, “It is better that I give her to you than that I should give her to any other man” (Genesis 29:19). When Jacob serves for seven years, he demands that Laban give him his wife. Laban does so, but it is his other daughter, Leah, who weds Jacob, not Rachel! Laban’s excuse is that it is the custom of the land to marry the eldest daughter before the younger daughter. Rightfully upset at this duplicitous trick, Jacob demands to be given his intended wife, Rachel. Knowing that he has Jacob on the hook, so to speak, Laban agrees—if Jacob will promise to serve him another seven years, then Rachel can be his bride after the wedding week of 061 Leah is complete (Genesis 29:21-27). Jacob agrees and marries two sisters within the span of two weeks (Genesis 29:28-30).

Biblical marriage customs reflect an ancient Near Eastern setting where specific steps must be taken to contract a marriage. Unlike today, where couples can make marriage decisions on their own, in ancient times the decision was traditionally made between men. When a couple was to be married, the groom and bride’s father would contract a marriage agreement. Most of these were oral agreements that were solemnized by an oath and the exchange of valuables or goods, such as furniture, clothing, textiles, jewelry, servants, or land. The gifts the groom agreed to bring was called a mohar in Hebrew (e.g., Genesis 34:12). The agreement and exchange of goods underscored both the economic aspect of marriage and the strengthening of social kinship bonds.

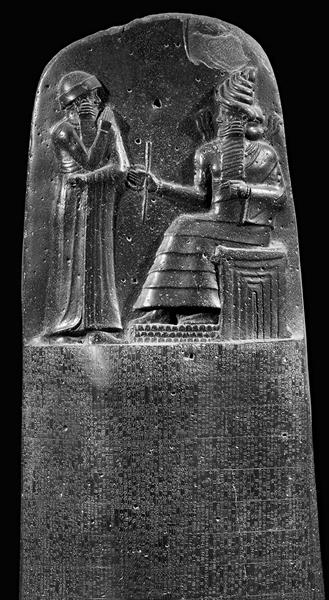

The importance of the marriage contract and the binding nature of these agreements is seen in various ancient law codes. The 20th-century B.C.E. laws of Eshnunna state: “If … he arranged for a marriage contract and libation [symbolic action] with her father and mother and took her, she is a wife; the day she is caught with [another] man she shall die; she shall not live.” The 18th-century B.C.E. laws of Hammurabi state: “If a man took a wife and did not arrange for her marriage contract, that woman is not a wife.”

Marriage agreements, whether written or oral, were very important, legally binding contracts. Both parties had to fulfill their terms of the agreement. Once the agreement was made, there was a waiting period (betrothal) to allow for the terms of the agreement to be met. For example, sometimes a girl might be betrothed for marriage when she was a child. In this case, the couple must wait until she was of marriageable age. In other cases, the groom might need some time to gather the wealth he had promised to the bride’s family.

Ancient Near Eastern marriage contracts help illuminate the marriages of Jacob, Rachel, and Leah. Looking closely at the contracts reveals the importance of the marriage events’ timing. Jacob commits to Laban that he will work seven years for the hand of Laban’s daughter. Jacob did not have any wealth to offer when he made the marriage agreement, so the marriage was delayed. Jacob’s labor was his gift. This works well for the timing of his first marriage. His marriage to his first wife (Leah) takes place when the marriage gifts have been paid. Unfortunately, Jacob does not marry the daughter he expected, and he must re-enter negotiations to marry Rachel. Jacob agrees to work another seven years. However, his marriage to Rachel takes place not seven years later, when the bride-price is paid, but seven days later! How could this be?

Some ancient Near Eastern marriage contracts stipulate that the marriage can take place before the bride-price has been paid in full. In these contracts, the bride-price is paid in installments. However, the final installment must be paid before the birth of the first child. According to Genesis 29, both Rachel and Leah live with Jacob in an intimate relationship, but only Leah bears children. Genesis 29:31 suggests God opens Leah’s womb right away because she is unloved. Rachel must wait.

It is not until Leah has seven children that God remembers Rachel, and she bears her first son (Genesis 30:20-24). Reading the story in light of the surrounding culture in which it arose provides another possible way to understand the narrative and birth of Leah and Rachel’s children. Leah has children right away because Jacob has fulfilled his marriage contract obligations. His seven years were served before they were married. However, Rachel’s son is born only after Jacob served for seven more years:

When Rachel had borne Joseph, Jacob said to Laban, “Send me away, that I may go to my own home and country. Give me my wives and my children for whom I have served you, and let me go; for you know very well the service I have given you.”

(Genesis 30:25-26)

Jacob’s request to leave coincides with the birth of Rachel’s first child. This is the key moment in Rachel’s narrative. The text subtly relays that her son, Joseph (who will grow up to save the Israelites), like Leah’s children, is born after the terms of her marriage agreement have been fulfilled. Jacob, the father of the Israelites, remains a man of his word, and Joseph is established as a legally legitimate child.

The biblical stories of barren women highlight the serious problem of childlessness in the ancient world. Infertility meant no child to love, to help with daily work, to provide for you in the afterlife, or to inherit land, money, or goods. Most important, without children there would be no one to replace the current generation. For a woman not to have any children posed a problem, both for herself and her husband. Couples navigated fertility issues in a number of ways, some of which were more reliable than others: prayer, magical practices, adoption, surrogacy, and at times a second […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.