Painstaking detail gives this small ivory carving an impressive realism—and shows how a well-regarded 13th-century B.C. Greek warrior would have looked in his boars’ tusk helmet. The carving, barely 3 inches tall, depicts a young man dressed for battle. His head is protected by the helmet, typically made of the tusks of 20 to 30 boars; an additional sheet of tusks covers the back of his neck, providing complete protection.

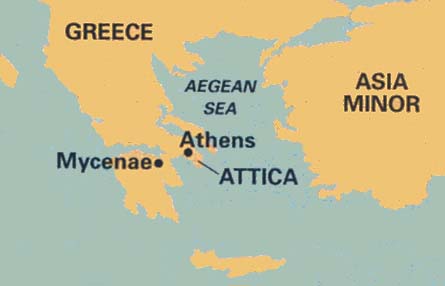

This small carving, found in a chamber tomb in Attica, Greece, was probably an inlay on a plaque: The small hole through the helmet indicates that the piece would have been attached to a wooden surface for display or to a piece of furniture as decoration.

Boars’ tusks—and the armor made from them—were highly prized by the Mycenaeans, who rose to power in the 16th century B.C. Their warlike society (Homer placed King Agamemnon, who attacked Troy, in Mycenae) brought them great wealth and power, but they were also serious hunters and skilled ivory carvers. From Mycenae, the culture spread throughout the Greek mainland and was a dominating presence for several hundred years, until civil war and invasion destroyed the kingdom at the end of the 12th century B.C.