Image Details

Photos by Erich Lessing

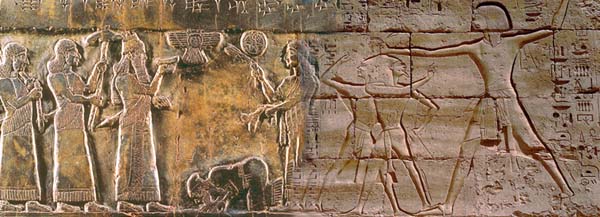

Squeezed between the expansionist empires of Assyria and Babylon to the north and Egypt to the south, the inhabitants of ancient Israel and Judah often suffered disastrous invasions at the hands of their neighbors. Fortunately for modern historians, those who triumphed liked to preserve their victories in stone. For example, in a relief commemorating his Palestinian campaign near the end of his reign, Pharaoh Shoshenq I (945–924 B.C.) is poised to strike down his puny Semitic adversaries, whom he grasps by their hair. The Black Obelisk of Assyrian conqueror Shalmaneser III (859–824 B.C.) shows another scene of triumph, in which he accepts tribute from a prostrate King Jehu of Israel (the two photos have been merged electronically). Extra-Biblical artifacts such as these can enhance and corroborate the Biblical account in many ways, writes author Kenneth Kitchen. When considered in light of the various calendrical methods used by the neighbors of ancient Israel and Judah, these three streams of evidence—the Biblical account and the Egyptian and Mesopotamian records—help establish the dates of Biblical events, including the reigns of such rulers as Solomon.