Image Details

Wayne T. Pitard

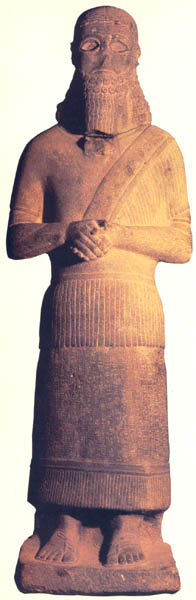

Excavated by bulldozer, as a farmer enlarged his field beside Tell Fakhariyah in northeastern Syria in 1979, this life-size statue (shown here, compare with next photo) bears an important inscription in two languages. It once stood in the temple of Hadad, the Syrian and Mesopotamian storm-god at Sikan, a city identified with Tell Fakhariyah. Sculpted from black basalt, probably in the ninth century B.C., the statue portrays Hadad-yit‘i, ruler of Gozan. The Bible mentions Gozan as a place conquered by the Assyrian king Sennacherib in the eighth century B.C. (2 Kings 19:12) and as one of the destinations where the Israelite exiles went after the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel in 721 B.C. (2 Kings 17:6, 18:11).

The bilingual inscription consists of a text in the Assyrian language, a dialect of Akkadian used by Assyrians in the second and first millennia B.C., and a translation into Aramaic, which came into common use in the Levant during the Persian period (539–331 B.C.) and was the vernacular in Palestine during the time of Jesus. The Assyrian text covers the front of the statues skirt, between the decorative fringes hanging from the waist and those hanging from the bottom of the skirt. The Aramaic translation of the Assyrian text—the oldest Aramaic text of substantial length ever found—appears on the skirt at the back of the statue.

This bilingual inscription offers possible solutions to two longstanding mysteries in the text of Genesis: the meaning of the name Eden and the apparent redundancy of “image” and ‘likeness” when God says ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Genesis 1:26).