Image Details

Erich Lessing

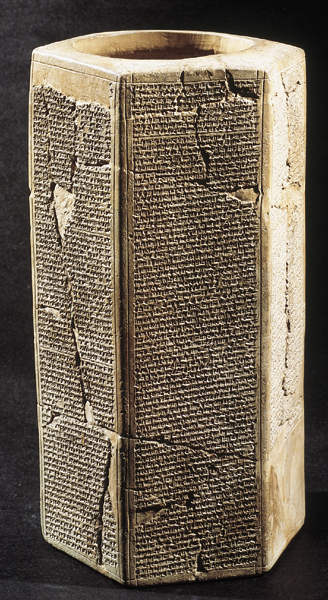

An Assyrian time capsule. The annals of King Sennacherib (704–681 B.C.E.) are impressed into this 15-inch-tall hexagonal prism. The cuneiform inscription was originally buried beneath the foundations of a royal building in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, in modern Iraq. Near the end of the text, Sennacherib writes: “When this palace grows old and falls into ruins, may some future prince repair its ruined parts! May he take notice of this inscription in which my name is recorded! May he anoint it with oil, pour out a libation over it and return it to its place!”

Sennacherib’s annals provide an independent (although not identical) account of the Assyrian campaigns in Judah during the reign of the Judahite king Hezekiah (727–686 B.C.E.): “Forty-six of [Hezekiah’s] strong walled towns and innumerable smaller villages I besieged and conquered As for Hezekiah, the awful splendor of my lordship overwhelmed him.”

In the biblical account, there is another player: God. First, we are told that God has instructed the Assyrians “to come up against [Judah], and destroy it” (2 Kings 18:25). Later, God apparently reconsiders, reassuring Hezekiah: “Do not be afraid I myself will put a spirit in him [Sennacherib], so that he shall return to his own land; I will cause him to fall by the sword in his own land” (2 Kings 19:6–7). The Israelites understood God as integral to their history, which is why author Paul Hanson suggests that examining their history is necessary for comprehending their God.