Dead Sea Scrolls: A Short History

Sidebar to: 60 Years with the Dead Sea Scrolls034

In early 1947 (or late 1946) an Arab shepherd searching for a lost sheep threw a rock into a cave in the limestone cliffs on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. Instead of a bleating sheep, he heard the sound of breaking pottery. When he investigated, he found seven nearly intact ancient documents that became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

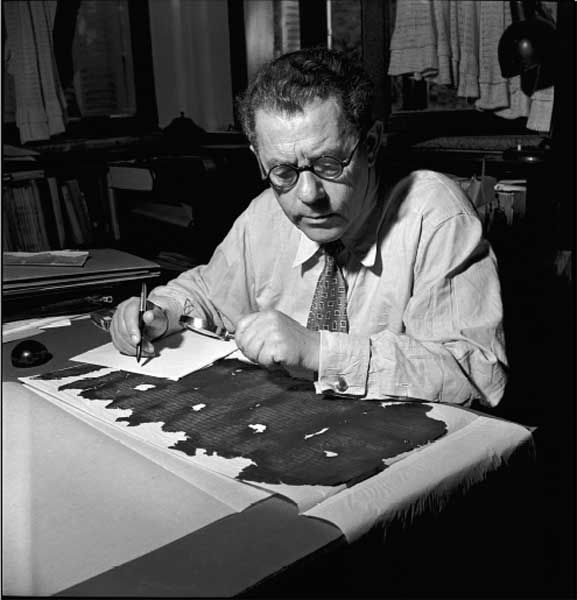

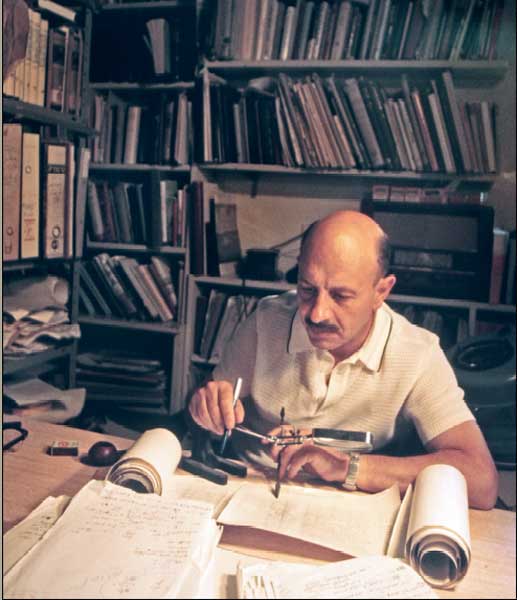

Three of the scrolls, including the Book of Isaiah, were acquired in Bethlehem by Eleazar L. Sukenik of The Hebrew University just as the United Nations voted by a two-thirds vote to partition Palestine, thus creating a Jewish state for the first time in 2,000 years. (See Past Perfect in this issue for Sukenik’s moving account.)

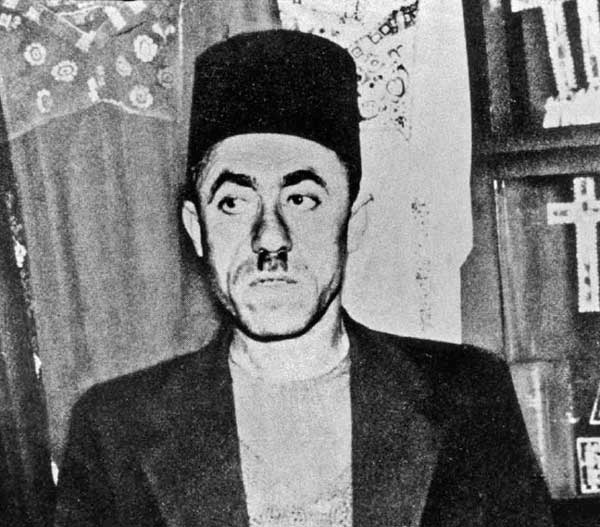

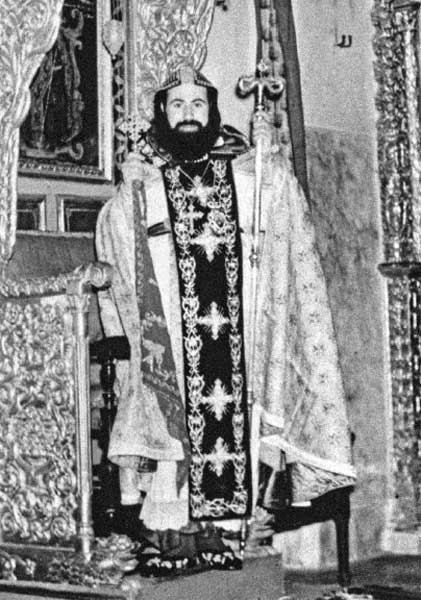

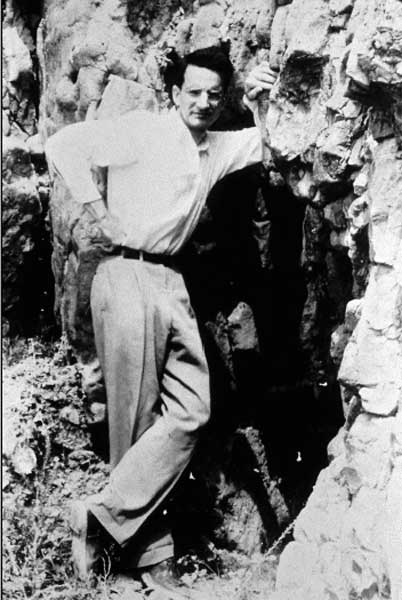

The other four scrolls were acquired by the Metropolitan Samuel, the Jerusalem leader of a Syrian sect of Christians. When he was unable to sell them in Jerusalem, he took them to the United States, where they were displayed in the Library of Congress. Still unable to sell them, he placed a classified ad in The Wall Street Journal offering them for sale. Through fronts, they were purchased for Israel by war hero and archaeologist Yigael Yadin, Sukenik’s son.

A special museum, The Shrine of the Book, was built in Jerusalem to house the scrolls.

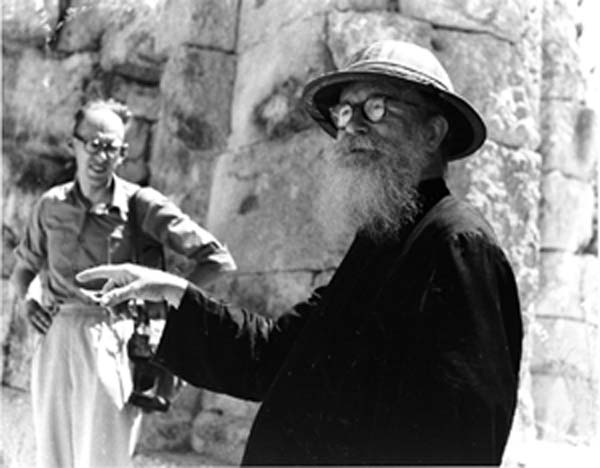

Père Roland de Vaux of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem, together with G. Lankester Harding, the British-appointed head of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, 035mounted an archaeological excavation early on at Khirbet Qumran, near the cave where the scrolls had been found (by that time, the Bedouin had also found a second cave). Since then, a debate has raged among scholars as to the relationship of the Qumran ruins to the scrolls. The majority of scholars believe Qumran was the monastery-like settlement of a Jewish sect known as Essenes, to whom the scrolls belonged. Other suggestions range from a caravanserai to a pottery factory.

Ultimately a total of 11 caves were found (mostly by the Bedouin) containing ancient manuscripts. Scholars date the scrolls between about 250 B.C.E. and about 68 C.E., when Roman legionaries overran the Judean Desert on their way to destroying Jerusalem and the Temple (which they did in 70 C.E.).

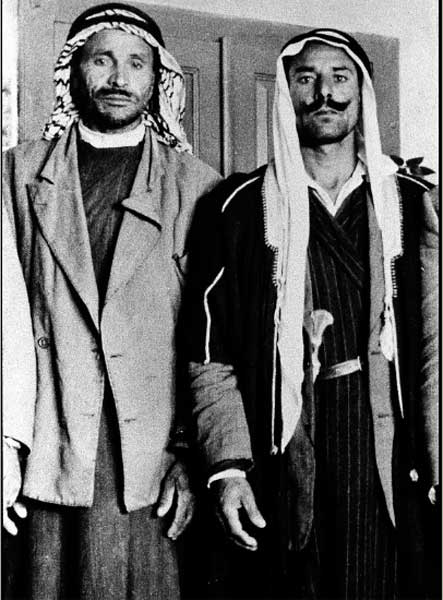

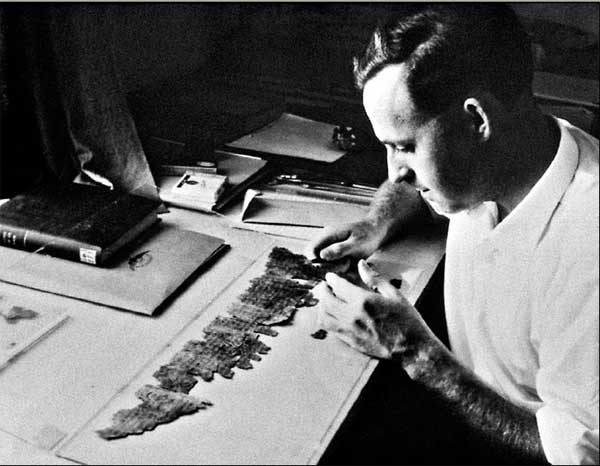

The most famous, or infamous, of the caves is Cave 4, found by the Bedouin practically under the noses of the archaeologists digging at the adjacent ruins. Cave 4 contained more than 500 different manuscripts, but all in tatters. About 80 percent of them had been looted by the Bedouin before the 036archaeologists discovered the cave. The archaeologists retrieved the remaining 20 percent, but they were forced to buy the other 80 percent, chiefly through an Arab middleman known as Kando (see James Charlesworth’s story in a forthcoming issue of BAR).

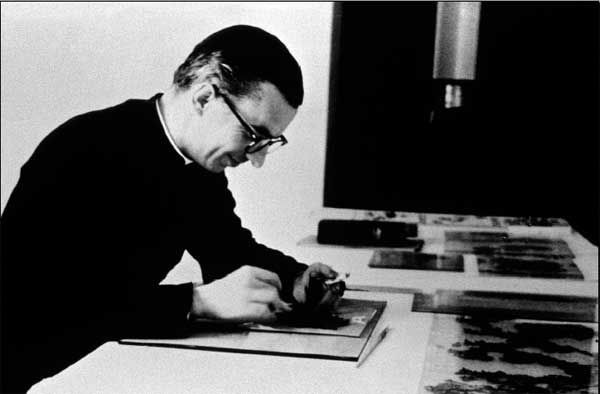

The publication of the Cave 4 fragments was assigned under Jordanian auspices to eight scholars. Over the years the publications of this team gradually dwindled to a trickle and finally disappeared. In the meantime, the unpublished texts were unavailable to the public or to other scholars.

In 1977, Oxford don Geza Vermes declared that the failure to publish these scrolls and make them publicly available was threatening to become “the academic scandal par excellence of the 20th century” (see Geza Vermes’s story in a forthcoming issue of BAR).

In the late 1980s, BAR took up the call, publicly demanding the release of the scrolls so that all scholars could study them. After the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel gained control of the scrolls in Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum (formerly the Palestine Archaeological Museum), but the Israelis did not change the situation. The scrolls remained under the control of the small, non-Jewish, practically nonfunctioning scroll-publication team.

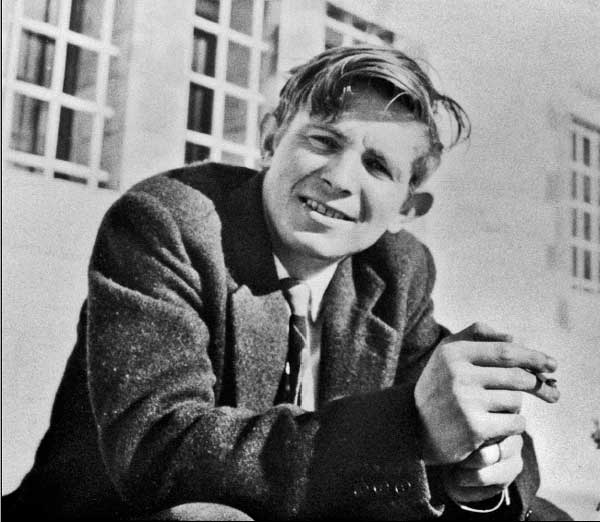

The then-editor-in-chief of the scroll team was Harvard’s John Strugnell, whose personal emotional problems, including alcoholism, were affecting his work (see Sidnie White Crawford’s story in the article “Dead Sea Scrolls: How They Changed Life”). After Strugnell gave a grossly anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist interview to an Israeli journalist 037(see Frank Moore Cross’s interview in this issue’s article, “Dead Sea Scrolls: How They Changed Life”), Israel finally replaced him with Professor Emanuel Tov of The Hebrew University (see his “Taking the Helm” in “Dead Sea Scrolls: How They Changed Life”). At first he, too, refused to release the scrolls, although, as Strugnell had also done toward the end of his editorship, Tov appointed additional scholars to the publication team, including Israelis.

The first break in the release of the scrolls came when the Biblical Archaeology Society published some unpublished texts that had been reconstructed with the aid of a computer, based on a private concordance of the Cave 4 fragments (see Martin Abegg’s story in “Dead Sea Scrolls: How They Changed Life”).

Then the Biblical Archaeology Society published a two-volume work of photographs of the unpublished scrolls, obtained in a still-mysterious way by Professor Robert Eisenman of California State University. Even now Eisenman declines to divulge how he obtained the photographs, although it was always clear they were genuine.

Finally, director William Moffett of the Huntington Library in California decided to release images of the unpublished scrolls on a microfilm strip that had been deposited in the library as a security measure in case the originals were lost. The Huntington’s decision to release its copy of the unpublished scrolls was announced at the top of the Sunday edition of The New York Times on September 21, 1991. Although Israel first considered suing the library (and the Biblical Archaeology Society), saner minds eventually prevailed, and the scrolls were declared open and available to all.

The scrolls have had an enormous effect on scholarship, principally in three areas: (1) the origins of early Christian thought; (2) the development of the Hebrew Bible; and (3) the history of Judaism and its varied religious beliefs during the period from about 250 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.

For more on these topics, download the e-book The Dead Sea Scrolls and Why They Matter from our Web site, www.biblicalarchaeology.org/DeadSeaScrolls.