Deities and Dogs—Their Sacred Rites

Sidebar to: Why Were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?040

In the ancient Near East, dogs are often associated with particular deities and the powers they wield. We cannot yet be sure with which deity the dogs in the cemetery at Ashkelon were associated. There are several possibilities, in several cultural guises, often interrelated as one deity merges into another.

But in the end, a common theme emerges—deities with healing powers are often associated with dogs.

According to a Phoenician legend, the leading deity of the city of Tyre, Herakles-Melkart, was credited with the discovery of purple. Actually, however, it was his dog who discovered the product for which the Phoenicians were world-renowned—purple dye, extracted from a gland in a Murex mollusk: Herakles was strolling along the beach with his dog and with a beautiful nymph named Tyrus. His hound discovered a Murex and bit into it. The dye from the snail stained the dog’s lips a bright purple, a color the nymph greatly admired. Herakles collected enough mollusks to dye a robe purple and presented this fine gift to the nymph. This discovery was celebrated on coins from Tyre, depicting a dog sniffing a Murex snail.11

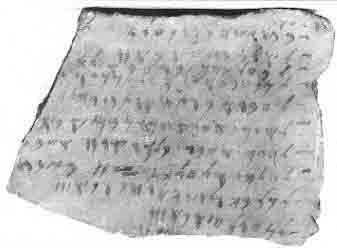

More pertinent, however, is a small (about 6 by 4 inches) mid-fifth-century B.C. limestone plaque inscribed on both sides in Phoenician; it was found in 1869 at the Phoenician port city of Kition on Cyprus.12

The Kition plaque lists personnel associated in some way with the temples of the goddess of fertility, Astarte, and a more obscure male deity, Mukol (vocalized variously as Mekal, Mukal or even Mikal). Mukol appears as part of a compound god name, Resheph-Mukol (rs

Resheph is known from Ugaritic and Aramaic inscriptions as the lord of the underworld (= Mesopotamian Nergal), lord of plague, pestilence and disease—and conversely the god of healing. William F. Albright suggested that the Phoenician god of healing par excellence, Eshmun (whose Greek equivalent was Asklepios), had a Canaanite precursor, Sulman (literally, “One of welfare”). The Canaanite underworld figure named Ras

Resheph-Mukol = Apollo-Amuklos could be the same sort of bipolar deity, embodying what seems to us (but not to them) mutually exclusive, contradictory aspects. At Ugarit, Resheph bore the title “Lord of the Arrow Resheph” (b‘l h

Apollo also has an ambivalent nature: besides being a god of healing, father of Asklepios and bearing the epithet Physician (Iatros), Apollo is also the god of plague. In the Iliad 1.43–52 an angry Apollo marches down from Mt. Olympus, carrying his silver bow, the arrows rattling in his quiver. He sends a plague upon the Achaean army by shooting a “tearing arrow” into them. “The corpse fires burned everywhere and did not stop burning.” For nine days Apollo bombarded them with arrows. As William J. Fulco and Walter Burkert so astutely pointed out, the “arrows of Apollo,” like those of Resheph (and we might add, those of Yahweh), signify pestilence.17 Conversely, Apollo’s image was capable of warding off plague. It was Canaanite Resheph-Mukal who bequeathed many attributes to the archer-god Apollo, god of healing, god of plague.

There may be a much earlier evidence of the bipolar Resheph-Mukol, or Mukal, in Late Bronze Age Beth-Shean. An Egyptian stela found there in a temple from stratum IX depicts a bearded deity who sits enthroned before two worshippers.18 The deity wears a high conical cap with two streamers down the back and two small horns protruding from the front—horns very much like those worn by Resheph, whose animal emblems included the gazelle. However, the seated deity is identified by the hieroglyphic inscription as “Mukal, the great god, lord of Beth-Shean.” From the same temple of Mukal comes one of the most superb pieces of Canaanite art, a beautifully carved basalt relief (probably an orthostat), 3 feet high, with the following scene: In the upper register a dog and a lion stand on their hindlegs engaged in battle. In the lower one, the dog is prevailing over the lion as he bites the haunches of the lion. It is tempting to link the victorious dog with the god Mukal.

It seems clear that the Greek Apollo 041inherited his darker side as god of pestilence as well as his brighter side as god of healing from Canaanite Resheph. It was this Apollo of Cypro-Phoenician lineage who bequeathed his name to the Roman city Apollonia, between Caesarea and Jaffa, which earlier had been named for Resheph, as the modern Arabic placename Arsuf still attests. Likewise, the worship of Apollo in Hellenistic Ashkelon probably bore more resemblance to that of Resheph-Mukol in Phoenician Cyprus than to the sun worship and youth cult of Apollo in Greece. One tradition has it that Herod’s grandfather served as hierodule (a temple servant) in the temple of Apollo at Ashkelon. The sacred dogs of Ashkelon, like the dogs and puppies at Kition, just might have been part of a healing cult in the tradition of Apollo-Resheph-Mukol.e

By classical times in Greece, Asklepios, the son of Apollo (= Resheph), had become more popular among the Greeks than even his father Apollo also a healing deity. The most famous shrine of Asklepios’ healing cult was at Epidaurus, where patients would come to spend the night in the dormitory (abaton) in the hope that Asklepios would appear to them in a dream vision and reveal a cure for the sleeper’s disease or illness. Or the clients might be visited during the night by surrogates of the god—sacred dogs and snakes whose “tongues” were believed to have a therapeutic effect on the clients. Professor Howard Clark Kee of Boston University provides this memorable image of the experience: “It is easy to imagine the vigil of the suppliants, lying in the total darkness of the abaton, listening for the padding feet of the priests or the sacred dogs, or the nearly noiseless slithering of the sacred snakes.”19

Among the temple personnel mentioned on the Kition plaque are builders, marshals, singers, servants, sacrificers, bakers, barbers, shepherds (who may have raised flocks for temple sacrifices), maidens (‘lmt, sometimes rendered “temple prostitutes”) and—relevant to our topic—dogs (klbm). In short, here we find dogs associated with a Phoenician temple, or temples, of Astarte and Mukol.

All of the personnel mentioned in the Kition plaque, including dogs, receive particular payments for services rendered.

The word “dogs” appears in the same line of this inscription with a much-disputed term, grm. According to one scholar, A. Van den Branden, the dogs were actually humans who served as male prostitutes, or sodomites, in the temple rituals. This is the service for which they were paid. The grm, according to Van den Branden, were “lambs” or “adolescent prostitutes” in the cult. Later he modified his interpretation and suggested that these two groups of temple prostitutes received their names—“dogs” and “lambs”—from the animal masks and costumes they wore.20 The masked humans symbolized an earlier era when bestiality, involving real dogs and lambs, was performed in the cult.

Van den Branden based his (mis)understanding of the text on the Kition plaque largely on a common but equally questionable interpretation of a Biblical text, Deuteronomy 23:18:

“You shall not bring the hire of a harlot, or the wages of a dog into the house of the Lord your god in payment for any vow; for both of these are an abomination to the Lord your God.”

Van den Branden’s argument is based in large part on this passage from Deuteronomy, in which most Biblical commentators contend that “wages of a dog” is parallel to “hire of a harlot”; a harlot (zonah) being a female prostitute, dog (klb) must, therefore, be a male prostitute.

I do not see the necessity, however, of assuming that “dog” in this passage is the male counterpart of a female prostitute. It is not sodomy or pederasty that is the abomination in the context of this passage; rather it is the “bad” money accruing from the services of a harlot or a dog. To use that kind of money to pay for a vow in the Jerusalem Temple would be an abomination to the Israelite deity Yahweh.

Professor Brian Peckham of the University of Toronto, an expert on the Phoenicians, has written a superb analysis of the Kition plaque in which he too discards connotations of sodomy and pederasty that some scholars have imputed to the terms klbm (dogs) and grm in the Kition plaque. He has also decisively dated the Kition plaque to about 450 B.C., precisely in our period. On the other hand, Peckham agrees with Van den Branden that the dogs (klbm) and grm were humans masked as animals, who participated in some kind of temple rituals. The people with klbm masks were masquerading as dogs; those with grm masks, as lions. The latter identification is based on the Hebrew gr (plural, grm) which means lions or, more precisely, lion cubs, since Hebrew grm usually refers to lion whelps in the Bible.”21

I prefer, however, to take a very literal interpretation of klb (dog; plural klbm) in both Deuteronomy 23:18 and in the Kition plaque. In both texts the authors are referring not to humans acting like dogs in cult dramas but to actual dogs that performed services in the sacred precincts of the Phoenicians. Moreover, grm (singular gr) in the Bible can refer not only to lion whelps but also to the young of any animal, such as the jackal in Lamentations 4:3; on this basis the grm in the Kition plaque refers to the antecedent “dogs” and should be translated “puppies.”

In the Kition plaque dogs and puppies (or better, their attendants) were thus paid a sum for services rendered, probably in the temples of Mukol or Resheph-Mukol. Thus, this plaque provides an important contemporaneous and complementary document for interpreting the hundreds of dog and puppy burials at Ashkelon.

Although I reiterate that we have thus 042far not found an actual temple or any other kind of architecture that can be associated with the dog burials at Ashkelon, I believe there was either a temple or a sacred precinct associated with the cemetery. We may yet find it.

The concentration of dog burials in a cemetery, the type of interment in unlined pits and the mortality profile of the dogs in the Ashkelon cemetery also resemble dog burials in Mesopotamia associated with the goddess of healing, Gula/Ninisina. Her healing cult flourished at several centers during the second and first millennia B.C.

Recently a temple dedicated to the goddess of healing was partially excavated at Nippur, in modern Iraq. A votive figurine of a man clutching his throat has been interpreted by the excavator, Professor MacGuire Gibson of the University of Chicago, as signifying the ailment of which the suppliant either hoped to be or was healed.22 In cuneiform texts the temple of this goddess of healing (Gula) is sometimes referred to as the “Dog House” (é-ur-gi-ra), and her emblem is the dog.23

At Isin, another site in Mesopotamia, about 20 miles south of Nippur, numerous votive plaques and figurines depicting dogs were found in another temple of the healing goddess Gula. But even more revealing for our purposes were the 33 dog burials found in the ramp leading up to the temple. They, like the Ashkelon dogs, were buried in shallow pit graves, the carcass then being covered with soil. Although the sample of dogs excavated at Isin is quite small in comparison with Ashkelon, nevertheless, the mortality profile of the two dog populations is similar: At Isin, puppies comprised nearly half (15 of 33) of the dog burials; the rest were adults and subadults. Like the dogs at Ashkelon, there were no signs that the Isin dogs had died of anything other than natural causes. Again like the dogs of Ashkelon, the Isin dogs were given careful burials regardless of age at death.24 At Isin, however, the dog burials are clearly related to the temple of Gula, the goddess of healing. They were once the dogs of Gula, the goddess of healing. They roamed about the sacred precincts and participated in the healing rituals. The dogs buried at Ashkelon probably did the same thing.