052

One of the Sea Peoples mentioned in late-second-millennium B.C. Egyptian texts (as well as others) is called the Shardana. Like the Philistines, the Shardana settled in the Levant during a time of great instability, when numerous powerful Bronze Age civilizations were collapsing.a

But where did they come from?

Scholars have long recognized the similarity in the names “Shardana” and “Sardinia.” Were the Shardana, then, displaced Sardinians who made their way to the Levantine coast? Although this is an intriguing possibility, there simply has been no evidence to support the claim—until our excavations at el-Ahwat in north-central Israel.

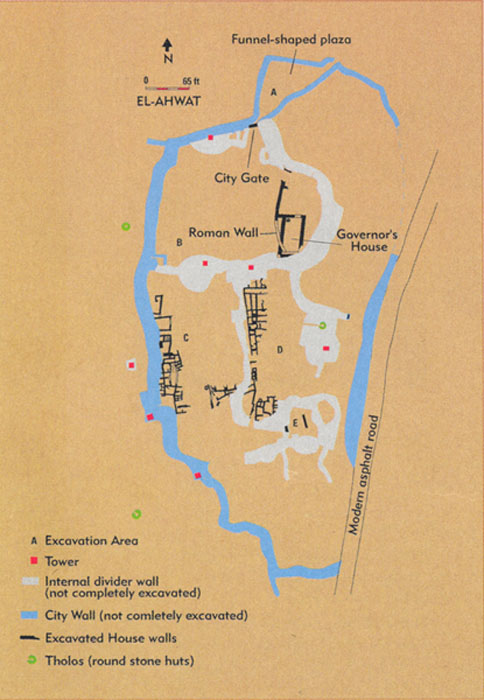

In 1992, soon after beginning excavations, we made some perplexing discoveries. We uncovered a 2,000-foot-long perimeter wall consisting of about 200,000 cubic feet of stone. Building this wall required an extraordinary investment of time and energy, yet the 8-acre settlement enclosed by the wall had only been inhabited a short time, from about 1220 B.C. to 1170 B.C. The wall was also different from other Canaanite walls: It tended to meander, changing directions for no apparent reason; and the northern road into the city descended as it approached the city gate, whereas all other walled cities in the region required visitors to mount a ramp to gain entrance.

We also unearthed a surprising number of small high-quality artifacts from the ruins of a 75- by 36-foot structure dubbed the Governor’s House. These included several 13th-century B.C. Egyptian scarabs, one inscribed with the name of Ramesses III (1182–1151 B.C.); a black stone seal carved with an image of a soldier on one side and a horse on the other; a bronze head (of a goddess?); carnelian beads; gold and silver jewelry; and an exquisite ivory ibex head (shown above). It seems that a high-ranking person lived in this house before el-Ahwat was abandoned.

We found no imported Mycenaean or Cypriot pottery or Canaanite painted vessels at the site, which is extremely unusual for a late-second-millennium B.C. Levantine settlement. Nor did the houses at el-Ahwat—labyrinthine structures with unusual built-in storage spaces—follow the plans of Israelite hill-country houses or Canaanite domestic architecture.

Perhaps our most perplexing find was a series of well-built stone corridors about 3 feet wide and up to 6 feet high. Some of these corridors led from houses into the city’s circuit wall, while others led into round stone structures with corbeled (or false dome) roofs. These round structures, reminiscent of Greek tholos tombs, were about 10 feet in diameter and 6 feet high.

In 1995 Haifa University historian Michael Heltzer pointed out that the structures uncovered at el-Ahwat (above) resemble huge stone structures called corridor nuraghi, built in Sardinia (below) during the early second millennium B.C. (We now know that corridors constructed in combination with false domes, like those at el-Ahwat, are found only on Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands east of Spain.)

The builders of el-Ahwat, it appears, were familiar with Sardinia’s Bronze Age Nuragic culture. Here, then, we may have the Shardana described in Egyptian texts.

The Shardana were fierce 053mercenaries. In Egyptian reliefs, they are depicted wearing distinctive horned helmets (similar examples have been found on Crete and Sardinia); they are sometimes shown fighting alongside pharaoh’s warriors and sometimes shown fighting against them.

As the evidence of the Amarna letters shows, the earliest bands of migrants probably left Sardinia around the 14th century B.C., stopping and settling at Crete, Egypt and the northern Levant before arriving at el-Ahwat. Possibly el-Ahwat was an Egyptian fort, built and staffed by Shardana soldiers but administered by an Egyptian governor, thus accounting for the luxurious objects in the Governor’s House. Or perhaps el-Ahwat was a Shardana colony under Egypt’s sway—one of many such settlements in the area.

I would like to suggest that el-Ahwat (an Arabic name meaning “the walls”) was actually the biblical city of Harosheth-ha-goiim, the military base of Sisera, who was a general under the Canaanite king Jabin (see Judges 4–5)b Sisera’s troops were ambushed by an army of Israelites called to battle by the female judge Deborah. The fighting took place in the narrow mouth of the Aruna Pass, which winds through the Carmel mountain range towards the Jezreel Valley, about 15 miles northeast of el-Ahwat. Since the hilly terrain made it difficult for Sisera’s chariots to maneuver, the Israelites decimated his army. As Sisera retreated to Harosheth-ha-goiim, many of his soldiers were slaughtered and he himself was killed.

Sisera could well have headed a coalition of Shardana living at the military base of Harosheth-ha-goiim/el-Ahwat. The name “Sisera” may derive from the Sardinian place-name “Sassari.” (A tablet found in Kammos, a Nuragic settlement on Crete, was inscribed with the name “Seisara,” which is almost identical to “Sisera.”) Moreover, the biblical reference to Sisera’s “nine hundred chariots of iron” (Judges 4:3) provides another link in the Sardinia-Shardana-Sisera chain of evidence: According to the Bible, the Philistines, another of the Sea Peoples, controlled all iron manufacture in the region.

Perhaps the rout of the Shardana forces led to the abandonment of their short-lived settlement at Harosheth-ha-goiim/el-Ahwat. The mercenaries may then have withdrawn to other Shardana settlements along the Mediterranean coast before eventually assimilating into Canaanite culture.