The Judahite King Hezekiah was facing a harrowing crisis in 701 BC. The full wrath of Sennacherib’s Assyrian army was poised to attack Judah. Knowing that he had only months to prepare, Hezekiah undertook major operations to defend his tiny kingdom from the most powerful force the ancient world had ever known. In Jerusalem, according to both the Bible and archaeology, he built a massive defensive wall and cut a water tunnel to redirect the waters of the Gihon Spring inside the city (2 Chronicles 32:1–7; Isaiah 22:8–11). As BAR readers know, the former is identified with the so-called “Broad Wall” uncovered in Jerusalem in the 1970s, while the latter is the celebrated Hezekiah’s Tunnel that can still be visited today.a

Assyrian sources further illustrate the events in vivid detail. In his own annals, Sennacherib says, “As for Hezekiah, the Judahite, I besieged 46 of his fortified walled cities and surrounded smaller towns … He himself, I locked up within Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage.” The famous Lachish reliefs, which once adorned Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh, show this siege in progress, including the wheeled battering rams, slingers, and archers who were involved in this violent campaign.

With the Assyrian invasion in full swing, we learn of another player in the dramatic events of 701 BC. The Bible claims that Sennacherib heard that “Tirhaqah, king of Cush, … has set out to fight against [him]” (Isaiah 37:9; see also 2 Kings 19:9). Sennacherib’s annals confirm this claim, though they do not mention the Cushite leader by name, simply noting, “the kings of Egypt, (and) the bowmen, chariot corps and cavalry of the kings of Cush assembled a countless force” that came to the aid of Judah and neighboring kingdoms that were under Assyrian threat.

But who was this Cushite king, known in Egyptian sources as Taharqa, who came to Judah’s defense during its hour of greatest need? We’ll return shortly to this intriguing figure and the important role he played in the international maelstrom of the late eighth century. But first we examine the fabled land of Cush—also called Nubia in later periods—and its rise to prominence in the first millennium BC.

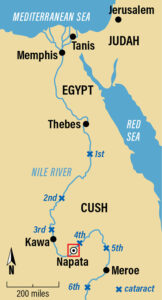

Cush is first attested in Egyptian texts from the early 20th century BC, during Egypt’s 12th Dynasty. The name referred to the area south of Egypt, in the regions of the second, third, and eventually fourth Nile cataracts. This area, found in modern-day northern Sudan, was rich in gold, a precious commodity coveted by the Egyptians. Between 2000 and 1750 BC, Egyptian pharaohs colonized and exploited the region, building numerous forts to administer and protect Egypt’s vital interests. During the Second Intermediate Period (1700–1525 BC), which included Hyksos rule over northern Egypt, Egypt’s grip on Cush eased, but the pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty immediately reconquered the area in the late 16th century.

To rule over this strategic region, the pharaoh appointed a senior officer titled “the king’s son of Cush,” often rendered by Egyptologists as “the viceroy of Cush.” Egypt’s domination of Cush endured throughout the New Kingdom (1550–1100 BC), during which magnificent temples were constructed in Nubia, including the iconic rock-cut temples of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Abu Simbel. Shortly after 1100, the New Kingdom crumbled, and Egypt was divided between kings ruling from Tanis in the north and other rulers who controlled southern Egypt from Thebes.

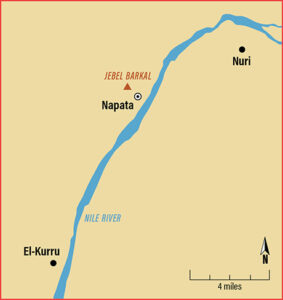

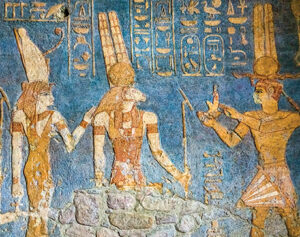

Thus, Cush was liberated from Egyptian hegemony, but not from the influence of Egyptian culture. For the next thousand years, Cushite royalty were buried in pyramids, wrote inscriptions in Egyptian hieroglyphs, and followed Egyptian canons of art and architecture. The patron god of Thebes, Amun-Re, was the principal deity of the Cushites. In fact, the mountain of Jebel Barkal, located at the Cushite capital and cultic center of Napata in northern Sudan, was thought to be the dwelling place of Amun-Re. Several temples to Amun-Re line the southern side of the mountain, including a large sanctuary first built during the reign of Thutmose IV (1400–1390 BC) that was continually renovated and expanded by later kings.

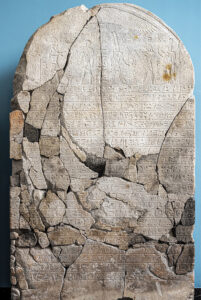

Around 800 BC, a Cushite royal dynasty emerged in Napata, beginning a long period of Nubian power and kingship that Egyptologists define as the Napatan period (c. 800–300 BC). The progenitor of this dynasty was King Alara, about whom little is known. His successor, King Kashta, was buried under a small pyramid at El-Kurru, the dynasty’s ancestral necropolis, located about 10 miles south of Jebel Barkal. It is Kashta’s son Piankhy, however, who is credited with bringing the Cushites to prominence. A stela discovered at Jebel Barkal recounts his military exploits in the north where, one by one, the petty kings of Lower Egypt capitulated to his Nubian army. In around 727, Piankhy took control of Memphis, the traditional capital of Egypt, which then became the seat of Cushite rule under Egypt’s 25th Dynasty.

With the Cushites firmly ensconced in Memphis, their kings rightfully became the pharaohs of Egypt. In a sense, these Nubian kings ruled two kingdoms: Cush, based at Napata, and Egypt, based at Memphis. This double kingship is reflected in Cushite royal iconography, in which Napatan kings wear crowns with a double cobra (uraeus). In 664, however, the Assyrians drove the Cushite rulers out of Egypt, returning the Cushite kingdom to its original borders in Nubia and effectively bringing the 25th Dynasty to an end.

With this context in mind, we now turn to what we know of Taharqa’s life and achievements. Taharqa was a younger son of the great king Piankhy. He ruled for more than a quarter century (690–664 BC) and was a prolific builder. In Nubia, he built Egyptian-style temples with pylons and pillared halls at Jebel Barkal and Kawa. One of his most stunning temples was devoted to the goddess Mut, the consort of Amun-Re. It was carved into the sandstone walls of Jebel Barkal and beautifully painted. Similarly, at the temple of Karnak in Thebes, Taharqa built a sanctuary beside the sacred lake as well as other smaller chapels, although his most prominent structure was a colonnade that now stands between the temple’s first and second pylons.

In addition, Taharqa abandoned the ancestral necropolis at El-Kurru for Nuri, a site on the other side of the Nile about 5 miles upstream from Jebel Barkal. There, he built the largest pyramid in Nubia (see “In the Shadow of the Pyramid”). Currently standing nearly 70 feet tall, the pyramid may have originally soared to a height of more than 165 feet. Nuri remained the royal burial ground until the end of the Napatan period in the late fourth century BC. Nearly two dozen pyramids from this time survive, and scholars estimate that as many as 80 may have once filled the necropolis.

Historians agree that Taharqa, the greatest of the Napatan kings, ruled from 690 to 664 BC. So how do we explain his presence in Judah in support of Hezekiah in 701 BC, more than a decade before his coronation? Scholars have long puzzled over this question, with some arguing the biblical references to Tirhaqah are anachronistic, since Egyptian chronology places another Nubian pharaoh, Shebitku, on the throne at that time.1 But common sense and the evidence from historical and textual sources suggest otherwise.

First, as the late Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen pointed out, the biblical authors clearly wrote their account of Sennacherib’s invasion at least a decade into Taharqa’s reign, since they also reference Sennacherib’s assassination in 680 BC (2 Kings 19:37; Isaiah 37:38). Thus, even though Taharqa was the Egyptian pharaoh when they were writing, the authors were presumably well aware he was not yet pharaoh in 701. By way of analogy, when one says that Queen Elizabeth II was born in 1926, they are not claiming she was also queen at that time, only that she eventually became queen. The biblical references to Taharqa are therefore proleptic, not anachronistic.2

Second, we know the Cushites practiced a type of collateral succession, in which the king was succeeded first by his brother, then by his eldest son, and finally by his younger son. King Piankhy died in 716, meaning Taharqa must have been born at least a few years earlier, making him about 20 years old in 701. His uncle Shabaka assumed the throne in 716, followed next by Piankhy’s eldest son, Shebitku, in 702. Thus, during the reigns of Shabaka and Shebitku, Taharqa was a crown prince, only ascending to the throne upon Shebitku’s death in 690. This may explain why the biblical writers identify him as king of Cush rather than pharaoh.

Third, several of Taharqa’s own royal stelae, discovered at the temple of Kawa, confirm this situation. These stelae, erected sometime after Taharqa ascended the throne, telescope a number of episodes from earlier in his career, including when he served as crown prince under his older brother, King Shebitku. For example, the text on Stela IV, dated to Taharqa’s sixth year (685 BC), tells us that he was summoned from Napata to Memphis by his elder brother, “his majesty King Shebitku,” and that he had with him “his majesty’s army.” The intent of this troop movement under Taharqa’s leadership (in service to his elder brother) apparently was for taking military action against Assyria in 701 BC. Similarly, in Stela V, Taharqa recalls that this event happened when he was 20 years old (which proves he was not a child in 701 BC, as some have argued). Taken together, these stelae confirm Taharqa’s critical role in Shebitku’s northern campaign against Assyria, even though he was still crown prince at the time.

Finally, it is notable that in the Hebrew Bible, Tirhaqah is only called “king of Cush” (melek kush) and not “pharaoh.” Other Egyptian rulers from the eighth to sixth centuries BC are identified in the Bible as pharaohs, particularly Necho (2 Kings 23:33–34; Jeremiah 46:2) and Apries (Hophra, in Jeremiah 44:30). The absence of any reference to Tirhaqah as “pharaoh” again suggests the biblical writers understood that in 701 BC Taharqa was simply a Cushite prince who perhaps ruled Cush on behalf of Pharaoh Shebitku in Memphis and thus was called “king of Cush.”

The timing of Taharqa’s campaign against Sennacherib might have been motivated by Egypt’s desire to take preemptive action to thwart any further Assyrian advance on Egypt. Pharaoh Shebitku clearly understood that if Judah and Philistia were conquered, Egypt would be the next domino to fall. The evidence suggests that Taharqa, while still a 20-year-old prince of Nubia, led a Cushite-Egyptian force to Judah on behalf of his brother, King Shebitku.

The full impact of the battle between the Cushite-Egyptian and Assyrian armies is uncertain. While Sennacherib’s annals claim to have defeated Taharqa’s army and taken prisoners, neither the Bible nor Cushite inscriptions offer any information about the outcome. There is no doubt, however, that Hezekiah benefited from this military engagement, as it certainly distracted the Assyrian war machine from its siege of Jerusalem and may have contributed to Judah’s ultimate survival.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. See Nitzva Rosovsky, “A Thousand Years of History in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter,” BAR, May/June 1992; and Dan Gill, “How They Met: Geology Solves Long-Standing Mystery of Hezekiah’s Tunnelers,” BAR, July/August 1994.

Endnotes

1. M.F. Laming Macadam, who discovered and originally published the Kawa stelae, maintained that Taharqa was only eight years old in 701 BC. See The Temples of Kawa, I. The Inscriptions (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1949), p. xii.

2. Kenneth A. Kitchen, “The Kawa Stelae of Taharqa,” in K. Lawson Younger, ed., Context of Scripture IV (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 18–19.