Visualizing First Temple Jerusalem

052

Visitors to Jerusalem understandably are often confused by the jumbled and disconnected layers of the past that exist side by side with the teeming modern city. Jerusalem at the time of the First Temple—the Jerusalem of the Bible, the Jerusalem of Solomon, the Jerusalem whose Temple was destroyed in 586 B.C. and whose residents were carried off to captivity in Babylon—this Jerusalem exists only in fragments today. These fragments, excavated in recent years,1 may be seen in various places but to appreciate them requires help. Now these excavated remains may be viewed in relation to each other thanks to a scale model on display in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.

Aided by a team of archaeologists, architects, guides and the designer, I was in charge of planning the First Temple period model.2 We started by reviewing three other models that depict Jerusalem during later eras. One, built by Professor Michael Avi-Yonah, is of Jerusalem at the time of Herod the Great, before the Temple’s destruction by the Romans in 70 A.D. Based on literary and archaeological evidence, this model, on view at the Holy Land Hotel, reconstructs the city as it looked 2,000 years ago. A second model, prepared by a resident, Stephan Illes, for the 1873 world fair in Vienna and now on display in the Citadel, shows Jerusalem exactly as Illes saw it in the 19th century.3 Anyone who wishes to appreciate present-day Jerusalem, as well as plans for its future, can examine another model, displayed at the Municipality Building, that lays out what city planners and architects project for Jerusalem in the coming decades. None of these, however, helped us plan a model for a time when Jerusalem was so poor in both literary and archaeological remains.

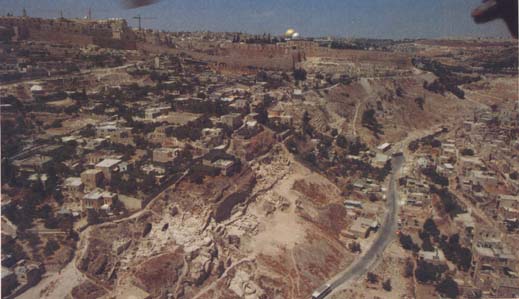

Based on very meager evidence, we built a 15-by-21-foot model. It sits, appropriately, in a hall located between the Broad Wall and the Israelite Tower, two prominent remnants of the First Temple period uncovered during the post-1967 Jewish Quarter excavations. Built to a horizontal scale of 1:250, the model depicts the topography and archaeological remains of Jerusalem during the last 130 years of the First Temple period—from the reign of Hezekiah at the end of the eighth century B.C. to the Babylonian destruction in 586 B.C. Geographically, the area encompasses about 1,000 dunams (250 acres), from the summit of the Mount of Olives on the east, the Turkish wall of the Old City on the west, the 053Damascus Gate area on the north, and the junction of the Hinnom and Kidron Valleys on the south.

Our first task was to reconstruct the city’s original topography. The centuries have taken their toll on the contours of Jerusalem. Debris has filled ancient valleys and construction has leveled hills. The best source of information remains a map prepared in 1912 by August Kümmel, a Leipzig schoolteacher who, ironically, never set foot in Jerusalem. Instead, Kümmel collected every measurement on the bedrock of the city, published and unpublished reports of scientific and other excavations that took place up to his time. He extrapolated this topography to create bedrock under the Old City and its environs. Kümmel’s map has yet to be updated, though the new model incorporates measurements taken during more recent excavations, especially those in the Jewish Quarter. To emphasize the city’s topography, the model’s vertical scale is a somewhat exaggerated 1:200, compared to a scale of 1:250 horizontally.

By showing the bedrock of ancient Jerusalem, the model emphasizes the dramatically changed topography of today. Many of the valleys in and around Jerusalem have been filled with as much as 50 feet of debris. The Transversal Valley, which descended 054from the present-day Jaffa Gate area to the Temple Mount, and the much smaller valley that ran from Jerusalem’s western hill (now occupied by the Jewish Quarter), northwards to the Transversal Valley, have both been completely filled and are not evident in the topography of present-day Jerusalem. The long valley that separates Jerusalem’s eastern and western hills, referred to in the Bible as simply “The Valley” and known in Second Temple times as the Tyropoeon Valley is much shallower today. Even the valleys of Kidron and Hinnom, which flank Jerusalem to the east, west and south, though still wide, have risen considerably. The Gihon Spring in the Kidron Valley, which once gushed from its hill flush with the valley floor, is now reached by descending 30 steps. The valley floor there is now 40 feet higher than it used to be.

To this topographical base we added to the model a re-creation of every significant archaeological discovery from the First Temple period, the bulk of them located on the eastern slope of the eastern hill, known as the City of David. They fall into four major categories: fortification walls, water supply systems, homes and public buildings.

Two portions of the wall that protected the ancient city were found by separate teams, the first in the 1960s led by Kathleen Kenyon on behalf of the British School of Archaeology and the second in the late 1970s and early 1980s headed by Yigal Shiloh of the Hebrew University. The wall was built in the eighth century B.C. adjacent to an even older, 19th-century B.C. Canaanite wall and was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. The model reproduces the wall sections recovered in both excavations, as well as a dirt path that ran outside of it. Also marked are lines representing the continuation of the wall around the western and northern portions of the city. These lines are only conjectures, however, because no sections of the wall have yet been discovered in those areas.

The walls in the model reflect the same diversity of stone and masonry found in the walls actually excavated. For emphasis, they are on a slightly larger scale than the rest of the model. The walls are in their proper places and reconstructed to match the highest point found in the excavations. The model does not attempt to reconstruct them to their original heights, which in most cases is not known.

A second important feature of our model is the ancient city’s water supply system. Jerusalem became a city because of the proximity of the Gihon Spring, the only constantly flowing spring in the vicinity. Three water systems from First Temple Jerusalem have been discovered and are represented on the model: Warren’s Shaft, Hezekiah’s Tunnel and the Siloam Channel. Warren’s Shaft, named after the 19th-century British archaeologist and surveyor who explored it, is a series of steeply sloping underground tunnels and a deep vertical shaft that permitted residents to safely reach the water of the Gihon Spring from above without going outside the city wall.

Hezekiah’s Tunnel was cut in 701 B.C. to prepare for an expected siege of Jerusalem by the Assyrian King Sennacherib. The S-shaped tunnel enlarged a natural fissure in the rock under the City of David and diverted water from the Gihon Spring to a pool near the southwestern corner of the city. This system is mentioned several times in the Bible, including 2 Chronicles 32:30, “It was Hezekiah who stopped up the spring of water of Upper Gihon, leading it downward west to the City of David.”

The Siloam Channel was a partially built, partially rock-cut channel that carried surplus water from the Gihon Spring along the eastern slope of the City of David to a reservoir at the southern tip of the city. There it supplied the gardens and orchards of the Kidron Valley, including the King’s Garden. It was apparently designed and constructed by King Solomon.

Both Warren’s Shaft and Hezekiah’s Tunnel are prominent features on the new model. Portions of the eastern slope of the City of David lift up or drop down to reveal the underground water systems; small, flickering lightbulbs create the effect of running water. The Siloam Channel, on the other hand, appears as a blue line.

Sections of private homes have also been excavated and can be found on the model. In about Hezekiah’s time, several houses were built outside the city wall, a very early sign of urban sprawl, as well as an indication that there must have been relatively long stretches of peace which made residents feel secure enough to forgo the protection of the city wall.

The most complete house excavated to date was within the city. It is known as the House of Ahiel because it contained a pottery sherd with the name Ahiel scratched on it. This is a four-room house, the typical Israelite residence of the First Temple period. Characteristically, it has three rooms set around a central courtyard and two rows of square monolithic pillars that supported a roof. A large re-creation of this house is on display in a room adjoining the city model.

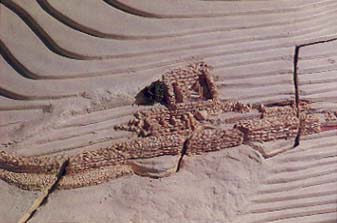

The House of Ahiel and its neighbors were built into an earlier structure called the stepped-stone structure. It is a monumental, sloping, stone-built structure that dates to the tenth century B.C. Its intended purpose is not clear. It may be the substructure of an important citadel. Or it may have been a retaining wall to create a level platform on which some massive public building stood. Only the sloping structure remains today, and it is carefully reproduced on the model.

Unfortunately, we know little about public buildings within the City of David, perhaps because they were built on the as-yet-unexcavated summit and not on the well-studied eastern slope. One happy exception is a large and well-constructed building called, because of the material used, the Ashlar House. Its features—an 055expansive 40-by-43-foot dimension and six pillars supporting a ceiling above the central room—are on the model.

The model also represents the towers and other structures uncovered on the Ophel (the topographic saddle that links the City of David with the sacred and royal precincts on the Temple Mount), including the discoveries described by Eilat Mazar in “Royal Gateway to Ancient Jerusalem Uncovered,” in this issue. To our regret, we know very little in archaeological terms of the Temple Mount itself at the time of the First Temple. Consequently, our model has only a plexiglass box to represent the maximum dimensions of the Temple as calculated by Yigael Yadin. We show no representation whatever of the royal palace because it has still not been precisely located.

An important array of First Temple structures appears on the western hill, in what is now the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. Two substantial segments of fortifications were discovered in this area. One is known as the Broad Wall—it is 23 feet thick—dated to the end of the eighth century B.C., the days of King Hezekiah. More than 200 feet of this wall have been cleared. This wall, like Hezekiah’s Tunnel under the City of David, was part of the scheme to provide Jerusalem with better means to withstand Sennacherib’s siege. It was the first city wall ever built on the western hill of Jerusalem, which was hitherto an unfortified suburb. The other structure on the western hill is a very well built tower, preserved to the surprising height of some 25 feet. It was built about 100 years after the Broad Wall and was standing at the time of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. Five Babylonian arrow heads discovered at the foot of the tower dramatize the fierce battle, although we have no evidence that the city was broken into by the Babylonians here.

Both wall and tower have revolutionized our view about the extent of Jerusalem from the eighth century B.C. to the Babylonian destruction of the city. This wall and tower, alongside the many fragmentary walls found on bedrock all over the Jewish Quarter, prove that the western hill was densely built up and fortified during the last 100 years of the First Temple period. Indeed it is now thought that this was the elusive Mishneh (or second quarter) referred to in the Bible (2 Kings 22:14). The Israelite Tower now stands three floors below the surface of the present-day street, in the basement of a house next to the model. It has thus lost much of its original effect. On the model the tower resumes its original splendor and its role as part of the fortification system of Jerusalem. We followed the guidance of Professor Nahman Avigad of the Hebrew University, director of excavations in the Jewish Quarter. He suggested that the tower was not an isolated element but part of a gateway; we completed a gate structure with a two-dimensional line on the surface of the model. The position, relationship and function of both the Broad Wall and the Israelite Tower—difficult to grasp in the area because of so much modern construction—are made clear on the model.

Although thousands of people lived here in First Temple times, we were unable to put even one complete house on this area of the model. This is because in the course of the intensive building that took place here during the Second Temple period, when the western hill became the residential quarter for Jerusalem’s upper classes, almost all signs of earlier inhabitation were destroyed. We did, however, place red dots on the model to indicate the remains of First Temple-period walls and pottery sherds.

No model of ancient Jerusalem could be complete without indicating tombs and quarries. We marked tombs on the model with black dots. A re-creation of one typical tomb is on view in a room next to the model. Yellow film shows the location of the quarries from which the limestone came that gives the city its unique look.

This new model of Jerusalem in First Temple times will help make the ancient city accessible to all who love her.

The model is located at the corner of Shonei Halachot and Plugat HaKotel streets in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. The model may be viewed only with a guided tour. Tours are conducted at 12:00, 12:30, 4:00, and 4:30 on Sunday through Thursday. Groups of 25 or more can arrange tours between 9:00 and 5:00 on the same days. For information call 02-286-288.

Visitors to Jerusalem understandably are often confused by the jumbled and disconnected layers of the past that exist side by side with the teeming modern city. Jerusalem at the time of the First Temple—the Jerusalem of the Bible, the Jerusalem of Solomon, the Jerusalem whose Temple was destroyed in 586 B.C. and whose residents were carried off to captivity in Babylon—this Jerusalem exists only in fragments today. These fragments, excavated in recent years,1 may be seen in various places but to appreciate them requires help. Now these excavated remains may be viewed in relation to each other thanks to […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

BAR articles describing First Temple Jerusalem include

The model was commissioned by the Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi Centre, the youth wing of the educational organization Yad Ben-Zvi, with support provided through the Jerusalem Foundation from the Sarah and Aaron Garfunkel Fund of the PEF Israel Endowment Funds. The designer was Yehuda Levi-Aldena who was aided by his wife Shirley.

See Helen Davis, “Jerusalem Model Rediscovered,” BAR 13:01.