032

Archaeology is full of surprises!

For 17 years, I have been investigating what some consider the most unglamorous of sites: ancient farms. I was not looking for, nor did I expect to find, the kind of breathtaking artifacts that tourists ooh-and-aah about in museums.

My search was for the way ancient farmers lived. I wanted to understand their daily lives, the way they worked and ate and farmed, and the way they related to the cities. My search was for a terrace, a dam, a wall, perhaps a few pots or an olive press. But surely not the romance and glory associated with figural mosaics.

Until recently most archaeological research in the Near East focused on ancient cities and major urban settlements. Little attention was paid to the agricultural settlements that supported these cities. Perhaps this is because ancient cities in the Near East are usually buried in tells, stratified mounds that are quite easily recognized. On the other hand, little farming settlements, often camouflaged by the surrounding landscape, are much more difficult to identify and study.

In recent years, however, archaeologists have been emphasizing how people lived, the way their societies functioned and the relationship between different parts of society. This may be reflected 034better in settlement patterns or terrace walls and olive pits than in gold jewelry.

Intrigued by this new approach, we have been directing our research to ancient farms near Jerusalem. These agricultural settlements supplied nearby cities, especially Jerusalem, with food and raw materials.a Ein Yael (ayn-yah-ELL), in the Rephaim (ref-ah-EEM) Valley, five miles west of the Old City of Jerusalem, is one such agricultural unit that supplied Jerusalem with food and olive oil produced in its oil presses. We are currently studying the agricultural and technological development of Ein Yael in the following periods: Canaanite (from the 31st to 11th centuries B.C.), First Temple (tenth to sixth centuries B.C.), Roman (first century B.C. to third century A.D.), Byzantine (fourth to seventh centuries A.D.) and Early Arabic (seventh to 11th centuries A.D.).

I first discovered Ein Yael on a summer day in 1980 while walking in the Rephaim Valley, between the Jerusalem neighborhoods of Kiryat Hayovel on the northwest and Gilo on the south. It was about 5 p.m., and the late afternoon light raked across the hillsides, outlining the shrubs and limestone outcrops with shadows. Looking toward the south, I suddenly realized that the terraces facing me were not just random stone walls, but appeared to be built in the form of a planned farm. Inspecting more closely, I discovered the wall bordering a terraced farm. Eager to learn about this farm, I returned to the site the next day and found water channels adjacent to each terrace. The channels were part of an irrigation system, which included stone valves used to direct the water flow. Clearly, this farm had been a permanent settlement, worked year-round and prepared to respond to changing water needs and to changing availability of water. Although the channels I found were relatively recent, probably no more than 50 years old, I was confident that the system was devised much earlier.

Geologists, archaeologists and botanists were brought in, and together we began to put together the pieces in order to understand how the Ein Yael farm actually operated. The farm took its name from the Arabic name of the spring on the farm, Ein Yalu; Hebraized it became Ein Yael. Aerial photos of the Judean hills revealed a number of additional farm units in the vicinity of Ein Yael. It became apparent that throughout history many farms, similar to Ein Yael, had been inhabited and worked in the Judean hills. By studying Ein Yael in detail, we hoped to learn about life in the agricultural communities that supplied Jerusalem with its food and were closely linked to its fate.

Limited excavations were carried out at Ein Yael from 1982 to 1984. Large-scale excavations began in 1986, when the Jerusalem Municipality decided to develop it as a recreational area.b Excavation proceeded in tandem with development of the site for visitors. We wanted to show the farm unit as an archaeological laboratory and as a living museum.

Throughout its long history two natural features influenced the character of the settlement at Ein Yael. One is the perennial spring for which it is named (ein in Hebrew means “spring”). The spring issues from a hillside cave on the south side of the settlement. The other natural feature is limestone terraces, typical of the Judean hills.

During all the centuries of its occupation, irrigation was necessary for the terraced farm at Ein Yael. To utilize the flowing spring water, some sort of collection system must have existed on the site as early as the Iron II period (tenth to sixth centuries B.C.). That the technology to build water tunnels and pools was known is demonstrated by the elaborate water systems at Megiddo, Hazor and other sites from the time of the Israelite monarchy.c

During the time of King Uzziah (169–733 B.C.), agricultural units were constructed throughout the land of Israel. The phrase “vineyards in the mountains” (2 Chronicles 26:9–10) suggests terrace farming. From this period (Iron II) at Ein Yael, we found only pottery and a wall. In future excavations, we will explore this level and earlier Canaanite levels. We are confident that more remains will be found, because across the Rephaim Valley from Ein Yael are sites already dated to both the Israelite and the Canaanite periods.

The spring at Ein Yael was certainly used in the Roman and Byzantine periods. We discovered pipes from these times buried beneath modern channels that lead from the upper terraces to the lower ones.

In front of the cave from which the spring flows, a beit mayan, or springhouse, was constructed in the Roman period and, with a few changes, has continued in use until the present time. Plastered channels inside stone galleries conducted the water from the springhouse to a collection pool. The water then flowed, via an open, plastered channel, into a large reservoir, and from there to irrigation channels leading to the 036agricultural terraces of the farm. Recently, this reservoir was repaired so that visitors to the site may see that Ein Yael was once a place of abundant water.

Limestone outcrops mark the Judean hillsides outside Jerusalem with patterns suggesting contour lines on a topographical map. At many times in Ein Yael’s history, stone walls were built on the outer edges of these terraces. Earth was brought to fill the area within the stone retaining walls. When leveled, the soil provided a plot for cultivation and for construction of buildings.

At the Ein Yael farm we count eight terraces. The uppermost level revealed evidence from all the periods of Ein Yael’s occupation: a portion of a wall from the First Temple period (seventh to sixth centuries B.C.), dated by its association with Iron Age pottery and with a stamp seal impression inscribed with a personal name; pottery dating to the Hellenistic (fourth to first centuries B.C.) and Second Temple (first century A.D.) periods, without any accompanying traces of buildings; remains of walls from a monastery or a church, a piece of a marble capital with a cross carved on it and an oil lamp bearing the image of Jesus on the cross—all dated to the Byzantine occupation of Ein Yael. Above these earlier structures, we discovered the remains of a farmhouse constructed in the seventh century A.D. (Early Arabic period).

But what we never expected to uncover at our farm was an exquisite Roman villa, cascading over several terraces. Although, so far, only a small portion of it has been excavated, it is quite possible that the villa covered an area of more than 32,000 square feet.

To enlarge the buildable surface area of the uppermost terrace, the Romans cut into the cliff face. On the bedrock of this terrace we found remains that include a corridor, a triclinium (formal dining room) and a third room, all embellished with elegant mosaic floors.1

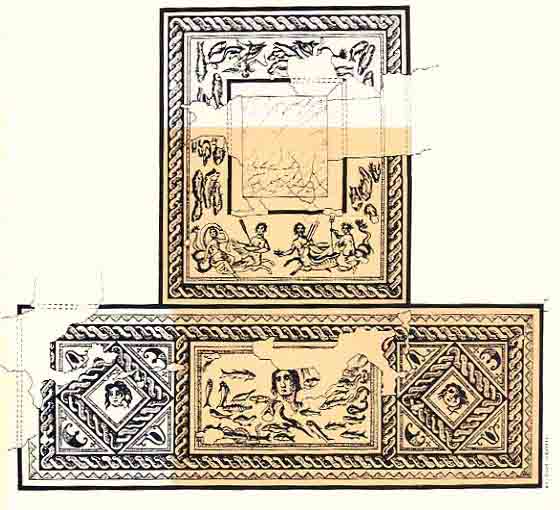

Along the length of the corridor, a long, narrow mosaic strip, consisting of several panels, depicts a familiar Roman theme: pastoral and agricultural cycles. Male busts personify each of the four seasons. In the corners of each panel, four birds surround each season. Each season’s special attributes appear in distinctive headgear: Winter wears a dark hooded mantle; spring is crowned with pink and yellow flowers and green leaves; autumn appears dressed in an orange and yellow toga with his head decorated by yellow and pink fruit with spiky green leaves; atop summer’s head perches a yellow, rolled-brim straw hat.

Winter and spring are next to one another as are summer and autumn. The two pairs are separated by a rectangular panel that contains a scene showing the weaving of wreaths or garlands. A satyrd sits on a rock with a basket of red flowers at his feet. He faces an 037otherwise bare tree on which is tied a brown ribbon with red flowers. Another figure, carrying a basket on his shoulders, approaches the satyr from behind. A Greek inscription on the lower edge of the panel has not yet been deciphered. The first three or four letters of the inscription are missing, and several letters in the center have been disturbed or repaired in antiquity. The only part that can be read with certainty is the last word—kaleh (good).

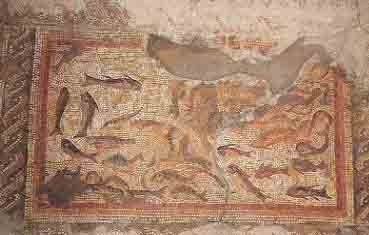

From the corridor, a doorway leads to the triclinium. Immediately within the entrance to this 14- by 16-foot formal dining room, a rectangular mosaic panel bears the face of the sea goddess Tethys, surrounded by fish and flanked by square panels with Medusae heads.

Diamond-shaped fresco panels decorated with flowers cover the walls of the triclinium. One small section of the fresco contains representations of two faces. We also discovered a number of pieces of fallen stucco, or fine plaster, decorated with faces, flowers and geometrical designs.

The elaborately adorned triclinium opened into another, smaller room also containing a mosaic. In this mosaic’s center is a medallion with a poorly preserved face. Four birds surround the medallion, one in each corner, separated by a lion, a lioness, a panther and a missing piece. The mosaic originally contained four theatrical masks; only two remain.

Searching for another mosaic floor in the villa, we excavated an area south of the western room. We discovered fragments of fresco adhering to three walls of this room, but we failed to find an intact mosaic floor. However, numerous stone tessarae scattered about in this area indicated that there had been a mosaic floor here that was destroyed in antiquity—by whom is not clear.

Preliminary soundings on the upper-terrace, west of the Roman villa, revealed the extensive ruins of a large building that may have been a Byzantine church. The possibility that this church commemorated Philip’s baptism of the eunuch, related in Acts 8, is discussed in “Did Philip Baptize the Eunuch at Ein Yael?” in this issue.

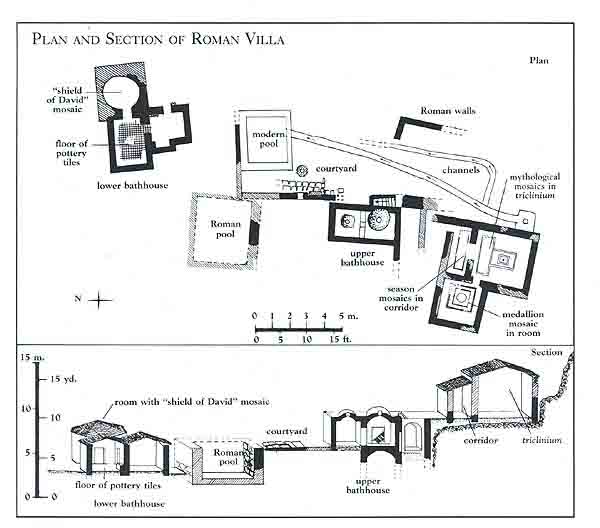

Descending from the uppermost terrace to the one below, we encountered an 8-foot-wide arch. Built of smooth-faced ashlars (rectangular, worked stone blocks), the arch may have served as an entrance to a working area to the east, not yet excavated. Next to the arched doorway on the same terrace level, two rooms of a 038Roman bathhouse still stand, complete from ceiling to floor (see plan and section). The roofs of these rooms and the top of the entry arch are at the same level as the floor of the triclinium on the terrace above.

The first room of the bathhouse, with a domed roof, contained pottery pipes within its walls. This was probably the warm room (tepidarium). In the second room, the barrel-vaulted roof was still intact, and under the floor of this room, we found the brick support arches of the hypocaust, or open area through which air could flow, heated by a nearby wood-burning furnace (preforium). The former entrance from outside to the second room of the bathhouse had been sealed in a later alteration.

In Roman times a public bath served as a place for entertainment and socializing. The classic Roman bath would have had three rooms—a cold room (frigidarium), a warm room (tepidarium) and a steam room (caldarium). Air heated by the furnace entered the hypocaust beneath 040the floor (suspensura), then flowed through pottery pipes into the bath above. At Ein Yael the bathhouses were for family use and are built on a much smaller scale than classic Roman public baths, but with many of the same features.

Both rooms of the Ein Yael bathhouse exhibited evidence of later occupation during the Byzantine and Early Arabic periods. Alteration of floors and walls stood out clearly from the original Roman ashlar masonry. Openings in the center of the two domes were probably later “improvements” when the rooms were reused for other purposes. In the first room, we uncovered an oven, dating to the Arabic period, located 3 feet above the level of the Roman floor. The oven and dome openings suggest that these rooms may have become cooking areas.

Outside the bathhouse, on the same terrace level, we uncovered a courtyard paved with ashlars. Built into this stone pavement was an olive press. Nearby, a hole in the floor appeared to be a vat for the extracted oil. Two more vats were also found. Leading into one of them, a pair of dolphins, carved in marble, formed a channel. According to the date of the pottery on the floor, this work area for processing olive oil was used during the Early Arabic period.

At the northern end of the paved courtyard, the terrace dropped off to a lower terrace where we exposed another bathhouse, even more elaborate than the upper one. This bathing installation comprised three rooms, two rectangular in shape and one circular. The Roman walls of these rooms are preserved to a height of 6.5 feet. To date, in the rectangular northern room, we have excavated part of the hypocaust, the heating system of the bathhouse. The floor of this room is paved with pottery tiles. In the southern room, only partially excavated, rectangular pottery pipes were found embedded in the plaster on the walls, probably to circulate hot air from the hypocaust.

In the last week of the 1988 season, we uncovered the mosaic floor of the circular room of the bathhouse, a floor encircled by a triple-twisted rope pattern, familiar to us from the mosaics in the living area of the villa. However, to our surprise a double-twisted rope in the center forms a hexagram, the familiar six-pointed star, or shield, of David (in Hebrew, magen David).

Painted frescoes decorate the walls of this circular room, preserved to a height of 5 feet. A brightly painted panel—marbleized in red on cream and bordered with alternating black, cream and green bands—embellishes the center of the east wall, directly opposite the room’s entrance.

The remains of the paintings on the walls are not panels, but combinations of geometric lines and swirls. Another section, framed in black lines, seems to contain representations of fruit—perhaps pomegranates—on a cream-colored background.

Not far from the lower bathhouse, on the same level, we uncovered one wall of an open pool. Dating to the Roman period, the pool was probably used as a collection pool, similar to the large pool described above.

The Roman villa at Ein Yael was built at approximately the end of the second century A.D., and remained in use until the middle of the third century. Evidence for the time of its use is of various kinds: pottery, oil lamps, the style of the mosaics, stamped roof tiles and the recent find of a coin.

Throughout the villa, many roof tiles were found, some of them bearing the stamp of the Roman Tenth Legion. Stationed in Jerusalem between the first and third centuries A.D., the Tenth Legion was deployed in building and engineering projects.2 It seems that the tiles in the villa at Ein Yael were either bought from the legion’s supply, or that the villa itself was built by the army. The late Professor Michael Avi-Yonah of Hebrew University excavated a Roman tile factory on the northwestern side of Jerusalem, in the area where the Hilton Hotel and the Binyanei Haomah Convention Center today stand. The location of this factory, close to the city center, indicates the presence of Roman building activity in the area.

In the 1986 excavation season at Ein Yael, a coin emerged from the villa bearing the name of Alexander Severus, the procurator of Judea. Minted in Caesarea between 222 and 235 A.D., the coin was no longer in circulation by 240 A.D.,3 indicating that the villa was in use at least until the middle of the third century A.D.

Why the villa went out of use is unclear. It may be that it was ultimately destroyed by an earthquake. We found boulders resting on the mosaics and in various other places at the site, but we found no evidence for 042other forms of destruction. The physical evidence and the villa’s location, built into the limestone cliff face, make the earthquake hypothesis the most plausible explanation for why this handsome villa was abandoned.

Not until the Romans imposed direct rule over Judea could there be a Roman villa on the outskirts of Jerusalem. The transfer of rule from native appointees to direct Roman proprietorship began after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D., and was completed after the Roman emperor Hadrian suppressed the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 A.D.), led by Bar-Kokhba. The destruction of Bar-Kokhba’s fortress at Betar, three miles west of Ein Yael, marked the end of the Second Revolt. It is possible that the section of Roman road we found, which passes directly by Ein Yael, was built by Hadrian to aid his efforts to conquer Betar. This section is part of a roadway connecting Jerusalem to the coast via Eleutheropolis (Beit Gubrin), southwest of Jerusalem. The existence of this Roman road may have been one of the factors in the choice of the Ein Yael term as the site upon which to build a Roman agricultural unit. The produce from the farms and villages in the area, including Ein Yael, would have supplied Jerusalem and the Roman Legion quartered there.

Hadrian, after quelling the revolt led by Bar-Kokhba, expelled the Jews from Judea, and propelled forward the process of Romanization of Palestine. This Romanization included the creation of Aelia Capitolina, the new Roman Jerusalem that bore no trace of its Jewish past, and a vigorous program of building roads, camps and settlements over the Jewish ruins of Judea. The Romans brought irrigation systems and Roman technology to Judea in order to stimulate agricultural development of the area.

Following expulsion of the Jews from the land, Hadrian expropriated Jewish properties and transferred title to his officers and government officials. The landlords used slaves or tenant-farmers to work their land. The landlord, whether he lived on the site or only occasionally visited, required a home that was appropriate to his status. Thus began the construction of extravagant villas on rural, agricultural properties outside of cities and fortresses, a practice known across the far-flung Roman world in England, Europe and North Africa, as well as in Judea.

In the Jerusalem area, in addition to Ein Yael and in close proximity to it, we have two further indications of Roman expansion into the countryside. In Yohanan Aharoni’s description of his excavations of Ramat Rachel, he observes that “A handsome building (strata II–III) was uncovered … in the center is a hypostyle, i.e. a courtyard with pillars running around it. The courtyard was paved with large stone slabs. … ”4 A bathhouse was found nearby, and both buildings belong to the second to third centuries A.D. In Manahat, approximately one mile north of Ein Yael, a tomb of Roman soldiers from the beginning of the third century was found. Both these finds, contemporaneous with the villa at Ein Yael, emphasize the Roman presence in the rural area of Jerusalem during the second and third centuries A.D.

Our excavations at Ein Yael and in the Rephaim Valley demonstrate the importance of Jerusalem’s rural areas during various periods of history. In the Canaanite era, the sparse population was scattered over an extended area. The Israelite period saw the beginning of terrace construction on the natural limestone outcrops and the initiation of planned family farms. When the Romans arrived, agricultural technology improved as wine and olive installations were added. Later, the Byzantines and Arabs continued to utilize the Roman installations. Although many terraces went out of use over the centuries, some of these ancient terraces continue to be maintained and cultivated even today.

Jewish sovereignty over the land of Israel ended with the Roman victory over Bar-Kokhba. Although Jewish settlement in the land never ceased during the intervening centuries, it was not until 1948 that an independent state of Israel, created by the United Nations, was reborn. Its flag bears the six-pointed star, now the preeminent symbol of Judaism and of Israel. This same star, discovered on the Ein Yael mosaic floor, was simply a common Roman decorative motif. The victorious Romans could never have believed that, almost 2,000 years later, their great empire would have vanished, and that the small, vanquished Jewish state would he reestablished in its land.

This article was written in cooperation with Sara Aurant. The original article was edited by Esther Weinstein.

Ein Yael Needs Contributions

Although the beautiful mosaics in the Roman villa have been restored and are now back in place at the site, $50,000 is needed for laboratory research and publication. Money is also needed for new educational workshops—between $5,000 and $6,000 for each workshop. You may earmark your contribution or designate it for the general preservation and excavation fund. Even small amounts can add up to something that helps us. Send contributions to: Gershon Edelstein, c/o Israel Antiquities Authority, P.O. Box 586, Jerusalem 91911, Israel.

Archaeology is full of surprises!

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Gershon Edelstein and Shimon Gibson, “Ancient Jerusalem’s Rural Food Basket,” BAR 08:04; Gibson and Edelstein, “Investigating Jerusalem’s Rural Landscape,” Levant 17 (1985).

Support for our work was provided by the Jerusalem Foundation, the Jewish National Fund and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

See Dan Cole, “How Water Tunnels Worked,” BAR 06:02.

A satyr, in Greek mythology, is a woodland deity usually represented as part human and part goat. He is known for his riotous and lascivious character.