035

It may or may not be the spot in the Jordan River where John the Baptist baptized Jesus, but Byzantine Christians seemed to think it was.

And it’s not on the western shore of the river, but on the eastern shore—in modern Jordan.

When it comes to locating places mentioned in the Gospels, the Byzantine Christians are often worth taking seriously. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on the supposed site of Jesus’ tomb only in the fourth century A.D., and for many years its identification was thought to be improbable, if not fanciful, because it was deep 036inside Jerusalem’s Old City walls. (In ancient times, graves were typically outside a city’s walls.) But the Byzantine identification has now been confirmed archaeologically.a

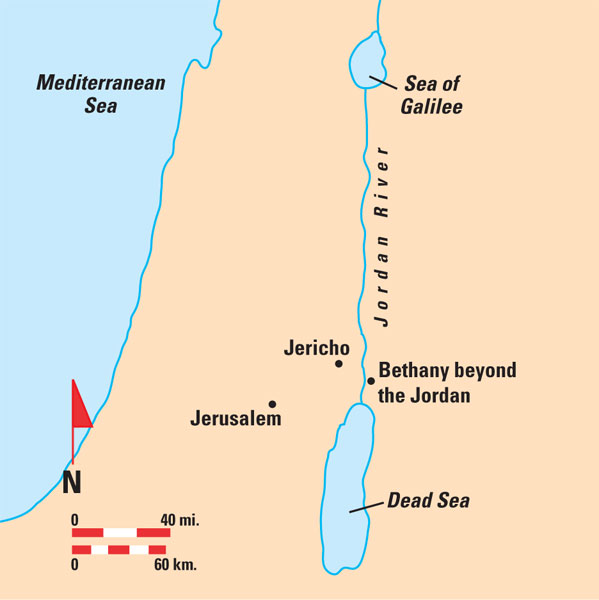

For a long time the archaeological evidence for the place of Jesus’ baptism could not be explored because it was in a Jordanian military area. Now, since the Jordan-Israel peace treaty of 1994, the Jordanians have painstakingly cleared nearby mine fields and the area is once again accessible to archaeologists, pilgrims and tourists. It is this new archaeological evidence that suggests we have indeed located the site called “Bethany beyond the Jordan” in the Gospel of John.

With its new visitor center, the site is fast becoming a major destination for Christian pilgrims from around the world. Located about 7 miles north of the Dead Sea, it is easily reachable from both Jordan and Israel. It is about a 40-minute drive from Amman and two hours by car from Jerusalem.

In the Jubilee Year 2000, Pope John Paul II visited this site during his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and it has been designated by the Catholic bishops of the Middle East as one of five pilgrimage sites in Jordan.b

In the Gospel of John, Pharisees from Jerusalem 037visit John at the place where he is baptizing. They want to know whether John thinks of himself as the Messiah or perhaps as Elijah (who will return to announce the Messiah).

John answers them, “‘I baptize with water. Among you stands one whom you do not know, the one who is coming after me; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandal.’ This took place in Bethany beyond the Jordan where John was baptizing” (John 1:26–28). (This “Bethany beyond the Jordan” should not be confused with the Bethany on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, which was the home of Mary, Martha and Lazarus.)

In a later incident, Jesus escapes from hostile Pharisees in Jerusalem and again goes “across the Jordan to the place where John at first baptized” (John 10:40). This site, too, appears to be located on the east bank of the Jordan; it is “across” the river if you are coming from Jerusalem and seems to be the same place earlier called “Bethany beyond the Jordan.”

In the first chapter of John’s gospel, in the paragraph immediately following the reference to “Bethany beyond the Jordan,” the text describes the descent of the Spirit on Jesus:

And John (the Baptist) testified, “I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it remained on him. I myself did not know him, but the one who sent me to baptize with water said to me, ‘He on whom you see the Spirit descend and remain is the one who baptizes with the holy Spirit.’ And I myself have seen and have testified that this is the Son of God.”

(John 1:32–34)

This passage represents the first—and perhaps the only—explicit Biblical reference to the manifestation of the Holy Trinity. The Baptist describes what he saw and heard when he baptized Jesus: In this description the Father speaks from Heaven, the Son is baptized and the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove.

Here, too, John first calls Jesus “the Lamb of God” (John 1:29, 35) and Jesus attracts his first disciples from among John’s followers (John 1:34–51).

It is, however, by no means universally accepted that “Bethany beyond the River” is on the east bank of the Jordan. Two of the most widely used Biblical dictionaries, the HarperCollins Bible Dictionary and the Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, tell us that the location of “Bethany beyond the Jordan” is “unknown.” And the famous Madaba map, a partially destroyed sixth-century mosaic map in a church in Madaba, Jordan,c seems to locate it west of the Jordan River. I say “seems,” not because there is any doubt as to the location west of the river, but because it is not called by the appellation “Bethany beyond the Jordan.” It is called Beth Abara, instead of Bethany. In the third century, the church father Origen, unable to locate the Bethany referred to in the first chapter of the Gospel of John, somewhat arbitrarily suggested emending the text to read “Beth Abara across the Jordan.” Beth Abara means “House of the Crossing,” possibly identifying a ford in the Jordan. A site of that name does appear in the Talmud. Following Origen, Eusebius in his Onomasticon 038(early fourth century) also refers only to this name, spelling it Bethaabara. In Jerome’s Liber Locorum (late fourth century) he calls the site Bethabara. Most of the ancient manuscripts, such as the major codices known as Vaticanus and Sinaiticus (fourth-fifth centuries), read Bethany in John 1:28. Nevertheless, Beth Abara apparently caught on and it is used in the Syriac version of the Gospels. And Beth Abara, not Bethany, appears on the Madaba map—on the west side of the Jordan. Beneath the name Beth Abara is a three-line legend in red telling us that this is the site of “The Baptism of St. John.”

Perhaps the Madaba map mosaicist, who lived east 039of the Jordan, understood “beyond” the river to mean west of the river—though for the original writer of the Gospel of John, “beyond” the Jordan clearly meant east of the Jordan River.

The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) mention Jesus’ baptism (Matthew and Mark mention that it is by John; Luke does not), but none of them indicates whether it occurred on the western or eastern shore of the Jordan (Matthew 3:13–17; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22). However, it seems likely that it would have been on the eastern shore. Jesus was coming from Galilee (again, explicit in Matthew and Mark). The normal route through the Decapolis (a group of ten Roman cities in the region) from Galilee would bypass a hostile Samaria by crossing the Jordan and proceeding south on the eastern side of the river.

Despite the Madaba map’s location of Beth Abara west of the Jordan, many other ancient authorities have the Baptist living and baptizing on the east side of the Jordan. In the early fourth century, Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, crossed the Jordan River and visited the cave where John the Baptist was said to have lived. Eusebius reports that she built a church there.

In about 530 A.D. the archdeacon Theodosius traveled to Palestine as a pilgrim and described a square-shaped church built on arched arcades and containing a marble column with an iron cross marking the spot where Jesus was baptized. The church was built on arches to allow water to pass underneath, but it succumbed to the Jordan River’s periodic floods and eventually collapsed. The site is east of the Jordan.

An early Christian tradition associated Jesus’ crossing of the Jordan with an Old Testament parallel: Just as Joshua led the Israelites across the Jordan into the Promised Land, so Jesus would cross the Jordan to lead the New Israel to salvation.1 Pilgrim tradition identifies the same site on the Jordan for both Joshua’s crossing and Jesus’ baptism. This tradition, as we will see, will help us identify the recent archaeological excavations as “Bethany beyond the Jordan.”

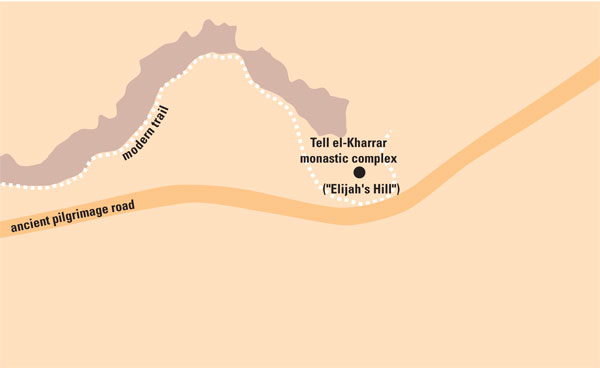

Another Old Testament parallel involves the prophet Elijah and his disciple and successor Elisha. Elisha insists on accompanying his teacher as Elijah goes from place to place, finally reaching the Jordan River. All know that the end of Elijah’s life is near. When they get to 041the Jordan, Elijah rolls up his mantle and strikes the water, which miraculously divides so that the two men cross on dry land. On the other side of the Jordan, a fiery horse-drawn chariot sweeps Elijah up to heaven in a whirlwind (2 Kings 2:4–14). The anonymous Pilgrim of Bordeaux (writing in 333) locates our site as the place where Elijah ascended to heaven. Ever since the Byzantine period, the main mound at the site we will explore here has been called Elijah’s Hill (Tell Mar Elias in Arabic).

The site now proposed as “Bethany beyond the Jordan” has been of archaeological interest since 1899 when Father Federlin, of Jerusalem, first investigated the site. He described a multi-church complex, including a church built on arches reminiscent of the arched church that Theodosius saw in 530 A.D.

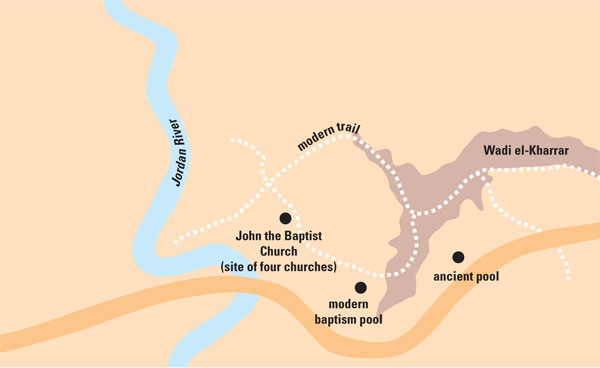

The site, today called the Baptism Archaeological Park, runs along a 1.5-mile-long wadi, the Wadi el-Kharrar. This perennial stream and riverbed runs from Tell el-Kharrar in the east to the Jordan River in the west. From 1996 to 2002 the area was excavated by Mohammad Waheeb of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities. On the tell, Waheeb’s team explored a Byzantine monastery as well as early-Roman-era remains. Adjacent to the Jordan River, Waheeb’s team has excavated a large multichurch complex from the Byzantine era. In between are several smaller Byzantine chapels, monks’ hermitages, caves, hermit cells, ceramic pipelines, large plastered pools and at least two caravanserai for pilgrims stopping here on their way to Mount Nebo, from which Moses viewed the Promised Land.

At the monastery complex on the tell, the Jordanian archaeologists unearthed not only architecture but also coins, pottery, stone vessels, inscriptions and other artifacts showing that the site was occupied from the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods (second century B.C. to second century A.D.) through the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods (fifth to eighth century A.D.), and 042again in the late Ottoman period (18th to 19th century).

The strongest evidence for a settlement from the time of Jesus comes from remains of distinctive heavy stone jars known from many Jewish communities from the first century B.C. until 70 A.D. These resemble the six stone water jars mentioned in the story of Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana (John 2:5–6).

Father Michele Piccirillo, of the Franciscan Archaeological Institute of Jerusalem and Mt. Nebo and one of the scholars who rediscovered the site in 1995, believes that these jars indicate a settled population at the site in Jesus’ time. A highly respected archaeologist, Piccirillo identifies the site as “Bethany beyond the Jordan.”

There were at least four churches in the monastery, as well as a sophisticated water conveyance and storage system, three pools and a surrounding wall designed mainly to prevent erosion of the tell rather than to offer protection.

The partly preserved mosaic floor of the main church includes a five-line Greek inscription near the altar area that reads: “By the help of the grace of Christ our God the whole monastery was constructed in the time of Rhotorios, the most God-beloved presbyter and abbot. May God the savior give him mercy.”

Another church in the monastery complex is built around a cave containing natural spring water—probably the same cave that Byzantine pilgrims called “the cave of John the Baptist.” The cave was transformed into the apse of a church in the Byzantine period; a wall with a door was built in front of the cave to form a chancel screen separating the main hall of the church (the nave) from the altar in the apse. Still visible are the square bases of the stone arches that supported the roof of the church nave.

An intriguing feature discovered during excavation of this cave-church is a manmade water channel that started 043at the front of the cave with spring water and traveled about 20 feet before spilling into the south bank of the Wadi el-Kharrar. The channel measures 10 inches wide and 6 inches deep, and is still covered in places with stone slabs. The water channel was cut into the marl beneath the floor of the church and lined with a lime plaster that is distinctively Byzantine in style and color. This channel may have carried away spring water used for baptisms inside the church or possibly the spring water that flowed naturally from the cave.

Beneath the mosaic floor of this church, buried in a small pit covered with a limestone capstone, was the skull of a man about 20 years old. As a result of a rare natural condition, the shape of a cross forms where the plates at the back of the skull converge. Waheeb suggests this may be why the skull was thought to be significant and why it merited a special burial place. He adds that the skull may have belonged to the priest Rhotorios, who founded the monastery.

An aqueduct from more distant springs brought water to three plastered rectangular pools within the monastery walls. Scholars are divided over whether these were baptism pools or water storage tanks. A wide staircase across the entire eastern side of the southern pool may be a telltale sign that it was a baptism facility. Smaller staircases provided access into the two other pools—perhaps further evidence of their use in baptism rituals. Storage tanks did not need wide staircases that take up so much space.

Turning from the tell to the shore of the Jordan, Waheeb’s team searched for the remains of the Church of St. John the Baptist built by St. Helena in the early fourth century and seen by the pilgrim Theodosius in about 530 A.D. The remains they discovered conform exactly to what the Byzantine texts described—a church built on arches, east of the river. The arches collapsed centuries ago and the stones now lie on the ground. There are in fact three churches at this site, superimposed on one another. Tradition has it that the church stands on the spot where Jesus left his clothes during his baptism.

In 1998, Waheeb discovered a fourth church near the shore—actually a chapel measuring just 13 by 20 feet—east of the three superimposed churches. A corridor-like structure with a marble staircase descends some 100 feetfrom the east side of the church of St. John the Baptist. The staircase includes 22 steps made of black marble. Its bottom has not yet been reached, though the lowest level excavated so far is already below the level of the water of the Jordan River. The small chapel is located just above what would be the end of the staircase. Pottery sherds found in the staircase excavation and the construction techniques both suggest a sixth-century date for the stairs. The walls of the staircase are inscribed with several crosses. That the steps descend lower than the level of the Jordan River suggests that the staircase was designed for pilgrims descending into the waters of the Jordan River for baptism.

This hypothesis may seem to be contradicted by the fact that today the river is about 300 feet from the stairs. In antiquity, however, the stairs may have led directly into the river. The Jordan is known to have changed its course many times in antiquity, due to heavy seasonal flooding in winter and spring. These floods no longer occur because the water is trapped by dams in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel. Today the Jordan is merely a trickle, but from Jesus’ time until the mid-20th century it annually expanded to nearly a mile wide.

The archaeologists have not yet found a sign at the site reading “Bethany beyond the Jordan,” but from all the evidence, both ancient and modern, it does appear that it has now been located.

It may or may not be the spot in the Jordan River where John the Baptist baptized Jesus, but Byzantine Christians seemed to think it was. And it’s not on the western shore of the river, but on the eastern shore—in modern Jordan. When it comes to locating places mentioned in the Gospels, the Byzantine Christians are often worth taking seriously. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on the supposed site of Jesus’ tomb only in the fourth century A.D., and for many years its identification was thought to be improbable, if not fanciful, because it was […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Dan Bahat, “Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?” BAR 12:03.

The other four are Mount Nebo; Mukawir (Machaerus), the Herodian palace where tradition says John the Baptist was imprisoned and beheaded; Tell Mar Elias, a site associated with the prophet Elijah’s birth; and the Sanctuary of our Lord of the Mountain in Anjara.

On the Madaba map, see “Jerusalem as Mosaic,” BAR 24:02.