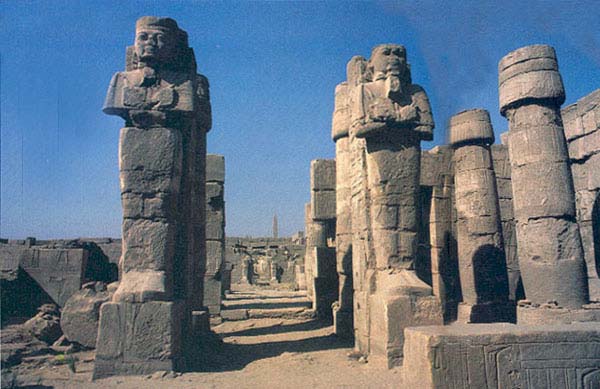

Winter of 1976–1977. I was in Luxor, in Upper Egypt, site of the ancient city of Thebes. As a member of the University of Chicago’s Epigraphic Survey, I was there studying the magnificent reliefs and recording the hieroglyphic inscriptions that almost cover the site.

In my spare time, I would work collecting whatever data I could find that might elucidate the late XIXth Dynasty (1293–1185 B.C.E.a), on which I was then writing my doctoral dissertation. It was in this connection that I found myself regularly studying a set of battle reliefs accompanied by extensive hieroglyphic inscriptions located in the famous Karnak temple.

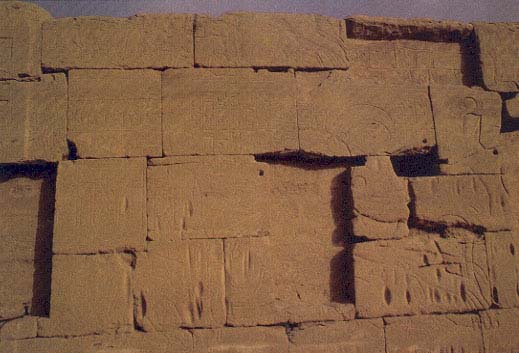

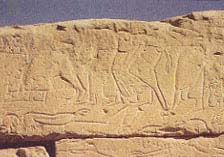

This particular scene is on the outer western wall of the Cour de la Cachette.1 The wall itself was originally about 158 feet long and 30 feet high and is composed of blocks about 50 to 63 inches long and 40 inches high. Time, unfortunately, has not been kind to the sculptors who created this monument. Except at the extreme left (north) end, the top of the wall is missing. Three scenes at the right (as one faces the wall) are no longer in place. The Romans took down the blocks forming these scenes, in order to widen the gateway to the right when they removed from Karnak the obelisk now in the Lateran Square in Rome. Sometime after the advent of Christianity, Egyptian Copts built their own structures against the wall and pulled out stones so that the holes thereby created in the wall would support sections of their buildings. Stones from the destroyed scenes of the wall are still strewn about in a field nearby. Fortunately, some of these blocks can be identified with particular locations in the wall.2

Near the left side of the wall, between two short engaged pillars that extend several inches from the wall, is a long hieroglyphic text—the text of the Peace Treaty that followed the great battle of Kadesh, on the Orontes in northern Syria in 1275 B.C.E., between Ramesses II and the Hittite army led by Muwatallis.

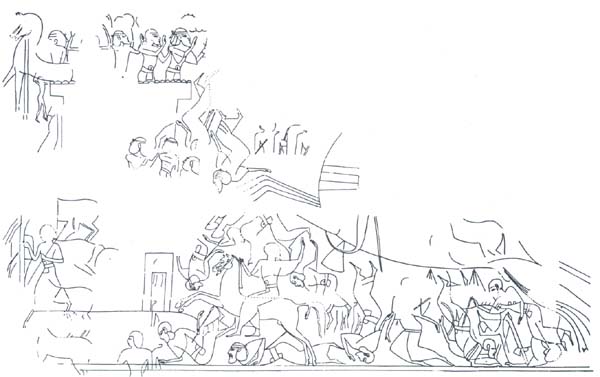

To the left of the Peace Treaty text are two battle scenes; to the right, two more. Then, farther to the right are—or were—six more scenes (two of the scenes at the far right are completely gone and must be entirely reconstructed, in part from blocks in the nearby field). The four battle scenes seem to frame the Peace Treaty, two on each side. To the right of these four battle scenes are other scenes that progress from left to right—the binding of prisoners, the collecting of prisoners, marching prisoners off to Egypt, presenting the prisoners to the god Amun, Amun presenting the sword of victory to the king (moving right to left) and finally a large-scale triumphal scene. The scenes stand in two registers, or rows, one above the other, except for the large triumphal scene at the right, which extended all the way from the top to the bottom of the wall. Each of the scenes also contains hieroglyphic inscriptions.

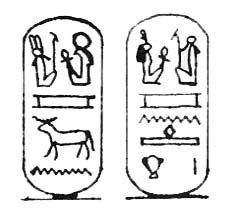

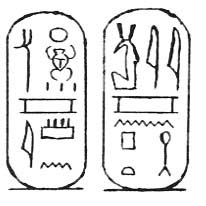

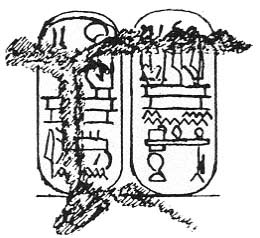

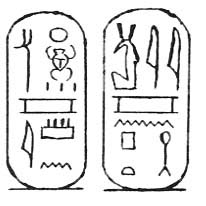

One of the things that especially interested me in the inscriptions was the cartouches—those oblong rings tied at the bottom that enclose the fourth and fifth names of the pharaoh. Both in the reliefs on the wall and on the loose blocks from these reliefs scattered about, all of the names in the cartouches had been usurped—that is, they had been partially erased and recarved with the names of a later king.

The names of the pharaoh that now appear in the cartouches belong to Sety II (1199–1193 B.C.E.). I wanted to look for the names of the earlier pharaoh under the names of Sety II. I should perhaps add that Egyptian pharaohs had five different royal names: The first four were given to him at his coronation: (1) The Horus name (so-called because it begins with a hieroglyph of the Horus falcon); (2) the Two-Ladies name (because it begins with a vulture and a cobra, both representing female goddesses); (3) the Golden-Horus name (because the Horus falcon stands on a symbol for gold); and (4) the prenomen (usually it is compounded with the name of the sun god). The fifth name is the king’s personal name given to him at birth. All five names together are called his titulary. Only the fourth and fifth names are enclosed in cartouches. And it was these I especially wanted to examine.

My work with the Epigraphic Survey had provided me with the techniques, training and experience for just such a task. The principal tool in examining usurped cartouches is the mirror. With a mirror you rake the light across the cartouche to deepen the shadows. This makes the carving stand out more sharply. It is not difficult to use this technique on a stone lying on the ground or even on one on the lower register of the reliefs. It is more difficult standing on a ladder 10 feet above the ground.

The technique employed by the usurping pharaohs—usurpation of cartouches was quite common all over ancient Egypt—was to hammer out and partly erase the original name. Then the surface was coated with plaster. But often the erased surface would first be scored to create a roughness that would better hold the plaster. Finally the new name would be incised in the plaster. Over the centuries, the concealing plaster tends to fall away, leaving visible traces of the carving beneath. In short, the very technique of usurpation often allows the traces to be unscrambled. In many cases, the traces are clearly visible.

This set of battle reliefs has dozens of usurped cartouches. But usurpation was not confined to the cartouches alone; it also appears on the full extended titulary of the pharaoh in the great triumphal scene, which originally was on the far right end of the wall.

The names of the latest versions in these cartouches and in the titulary belonged, as I said, to Sety II. Because of the statements of earlier scholars who had seen the wall, what I expected to see beneath the upper version were the names of Ramesses II. To my surprise, when I began examining these cartouches closely, I discovered they had been twice usurped. The original name had been partially erased; a second name had been incised on plaster that covered the original name; then that name on the plaster had been erased and replaced with the name of Sety II.

It gradually became clear that the name below Sety II was Amenmesse (1202–1199 B.C.E.), perhaps Sety’s half-brother. But below the name of Amenmesse was not the expected Ramesses II (1279–1212 B.C.E.), but Merenptah (1212–1202 B.C.E.)!b This, as we shall see, had extraordinary consequences.

From a close examination of the cartouches on these reliefs, on the loose blocks and in the Cour de la Cachette, I could see that Pharaoh Amenmesse had the cartouches of Merenptah hammered out and partly erased. The surface was then coated with plaster, and the usurping names incised. Next, Sety II had the cartouches of Amenmesse partially erased by scraping away the surface of the plaster; he then had his own names incised into the plaster. The original names, those of Merenptah, were carved deepest and at a uniform depth. The first usurper, Amenmesse, carved his signs a little more shallowly. Moreover, these names were cut partially in the stone and partially in the plaster, and the depth varied. Sety II’s erasure, by scraping away the name of Amenmesse, was quite thorough, leaving only scant traces of Amenmesse’s name. But Sety did not remove Merenptah’s name, which had been carved deepest. The net result is that the most visible names now to be seen are those of Merenptah beneath and those of Sety II above.3

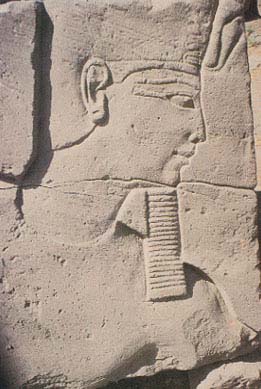

A small confirming detail is found on a stray block that clearly once fit into scene 10, which depicts the spoils of the campaign being presented by the pharaoh (now almost completely missing from the scene) to the Theban deities (also now missing). The stray block I refer to is lying in the field nearby; it bears the visage of a pharaoh. We have many depictions of Ramesses II, and some of Sety II also, but this visage does not resemble either of them. The closest parallels to this visage are found in the indisputably identified visages of Merenptah from his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, on the other side of the Nile from Thebes. Thus the evidence from the visages reinforces the epigraphic evidence.

What all this demonstrated was that the reliefs represent the military exploits of Merenptah rather than those of Ramesses II. As we will see, this makes a great difference. It will, among other things, allow us to identify the oldest pictures of Israelites ever discovered, engraved more than 3,200 years ago, at the very dawn of their emergence as a people.

Earlier scholars4 who attributed the battle reliefs to Ramesses II were misled by the Peace Treaty text between Ramesses and the Hittite king Hattusilis III that alone occupied the panel between the pilasters and was framed by the four battle scenes. Moreover, a horizontal hieroglyphic inscription that runs just under the cornice at the top of the wall proclaims that the wall was built by Ramesses II. True, the wall was built by Ramesses II, but that does not necessarily mean that all the carvings on the wall are his!

When I carefully examined the two battle scenes to the left of the Peace Treaty text, I found that they were both carved over earlier reliefs, which the later engraver had attempted to erase. The erasure was not very thorough, however, and many traces of the earlier engraving were visible. Whoever had attempted the erasure then used plaster to cover the deeper strokes in the original engraving. By a careful examination, the earlier scene can be identified. It displays a concentration of horses moving to the left with water at the bottom. This combination is well known as the subject matter of the battle of Kadesh of Ramesses II. This material extends, however, only up to the Peace Treaty text, and in any event was covered by the later battle scenes. To the right of the Peace Treaty, the Merenptah reliefs were carved onto a blank, previously uninscribed, wall surface. The erased earlier material under the scenes to the left is clear evidence that Ramesses II had started the decoration of this wall,5 but did not use the area to the right of the Peace Treaty text.

Accordingly, we can now quite securely date these four battle reliefs—two on each side of the Peace Treaty—to the reign of Merenptah.c

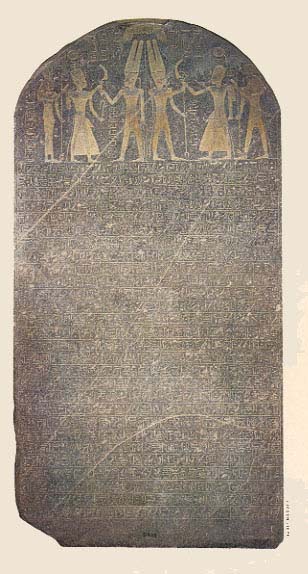

Having done this, the question naturally occurs to any Egyptologist as to whether Merenptah’s battle reliefs, as we may now call them, can in any way be related to the famous Merenptah Stele (Cairo no. 34025), one of the major stars in the Cairo Museum. The reason for the extraordinary fame of this stele—even outside the coterie of Egyptologists—is that it contains the earliest known mention of Israel; for that reason it is also known as the Israel Stele.

The Merenptah Stele was discovered by Sir Flinders Petried in 1896 in the ruins of Merenptah’s funerary temple in western Thebes. Interestingly, a fragmentary duplicate copy of the text, which contains part of the critical lines we will be discussing, was also found inside the Cour de la Cachette, beside the long inscription of Merenptah’s victory over Sea Peoples and Libyans in his fifth year, and quite near the very battle reliefs we have just dated to the reign of Merenptah.

The stele in the Cairo Museum, which contains the complete text, stands 7.5 feet high and half that wide. It is made of black granite. Originally it was a stele of Amenhotep III, also known as Amenophis III (1386–1349 B.C.E.). By this time the reader should not be surprised that Merenptah, who demolished Amenhotep III’s funerary temple to build his own, also appropriated and reused the reverse side of the stele. The text we are concerned with is carved on the verve, or back, of Amenhotep’s stele. In the semicircular top (the lunette) of the verve is a depiction of Merenptah receiving the sword of victory from Amun (twice) with Mut in attendance at the left and Khonsu at right. Carved in Merenptah’s fifth regnal year, the text as a whole records Merenptah’s overwhelming defeat of the Libyans and their Sea Peoples allies. But Merenptah also alludes retrospectively to an earlier campaign he conducted into Canaan.

This retrospective allusion, in the last two lines of the hieroglyphic text, reads as follows (the critical portions have been italicized):

“The princes, prostrated, say ‘Shalom’;

None raises his head among the Nine Bows.

Now that Tehenu has come to ruin, Hatti is pacified.

Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe. Ashkelon has been overcome.

Gezer has been captured.

Yano‘am was made non-existent.

Israel is laid waste (and) his seed is not.

Hurru has become a widow because of Egypt.

All lands have united themselves in peace.

Anyone who was restless, he has been subdued by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ba-en-Re-mery-Amun, son of Re, Mer-en-Ptah Hotep-her-Ma‘at, granted life like Re, daily.”e

This text was long dismissed by some scholars as simply a literary allusion with little basis in fact, a kind of poetic hyperbole.6 Other scholars hesitantly granted it some historical value, especially because Merenptah took the title “Subduer of Gezer.” He would be unlikely to adopt this title, obviously intended to reflect his achievements, if it were not soundly based on fact.7

The connections we are about to make strongly buttress the conclusion that the description of Merenptah’s campaign in Canaan was actually based on solid fact.

The first thing I noticed when I began to consider whether there is any connection between the battle reliefs in the Karnak temple and the campaign in Canaan described on the Merenptah Stele was that one of the four battle scenes (the one to the bottom right of the Peace Treaty, which I number scene 1) contains a hieroglyphic identification of the site of the battle: Ashkelon. Ashkelon is also mentioned in the Merenptah Stele: “Ashkelon has been overcome”! Was the appearance of a battle at Ashkelon on the wall of the Karnak temple and a reference to a battle at Ashkelon in the Merenptah Stele merely a coincidence? I searched the other three battle scenes for identification of the sites, but there is none—or at least none has been preserved.

But this brought to my attention another “coincidence.” On the wall of the Karnak temple, Merenptah had four battle scenes carved (two on each side of the Peace Treaty); one of the battle scenes could be identified as Ashkelon. In the Merenptah Stele, four names appear to identify his victories in Canaan. One of them is identified as Ashkelon.

The other three victories mentioned in Merenptah’s Stele are Gezer, Yano‘am and Israel. Might it be possible to identify the other three battle scenes with these three designations?

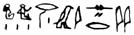

Notice that I have not referred to the four designations in the Merenptah Stele as sites, or places or even geographical locations. Although I could characterize Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am in this way, that is not true in the same sense with respect to Israel.

Moreover, this difference is emphasized in the hieroglyphic text of Merenptah’s Stele. Hieroglyphic writing consists not only of signs that have phonetic value—that is, are to be pronounced or vocalized—but it also includes other signs that have no phonetic value and are not intended to be vocalized. Their sole function is to indicate the category or kind of word to which they are attached. This kind of hieroglyphic sign is called a determinative.

The determinative used in the Merenptah Stele with the names of the three Canaanite city-states—Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am—is the familiar determinative regularly used for city-states that formed the Egyptian empire in Syria-Palestine during the New Kingdom period (1570–1070 B.C.E.). The name of Israel, however, is written on Merenptah’s Stele using a different determinative— —that is usually reserved for peoples without a fixed city-state area, or for nomadic groups.

—that is usually reserved for peoples without a fixed city-state area, or for nomadic groups.

This is especially noteworthy because Merenptah’s scribes were very careful in their use of determinatives in their other inscriptions made during year five of his reign, which describe the defeated Libyans and Sea Peoples.8

As the case for a connection between Merenptah’s battle reliefs in the Karnak temple and the victories described in Merenptah’s Stele began to look stronger, I looked for further parallels between the battle scenes, on the one hand, and the description in the stele, on the other.

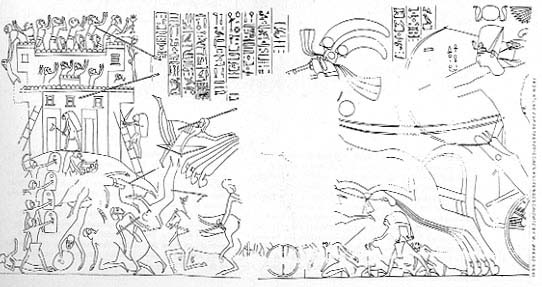

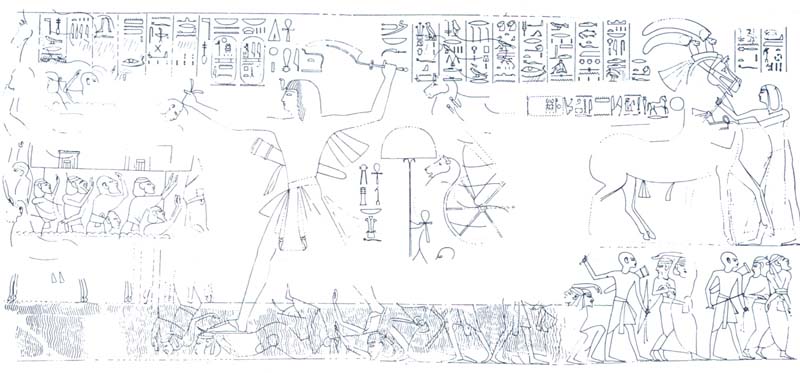

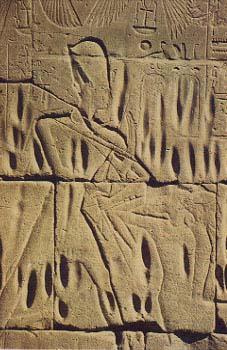

The next thing I noticed was that the relief of the battle of Ashkelon (scene 1) showed the siege of a fortified town. The pharaoh’s horse and chariot team are at the far right, with the enemy fortress at the left in a balancing position. A siege ladder can be seen resting against the town wall, which has a crenelated top. The two battle reliefs to the left of the Peace Treaty also depict sieges of fortified towns, also with crenelated tops of walls.

The fourth battle scene, to the right of the Peace Treaty and above the siege of Ashkelon, is, unfortunately, only about half preserved. The upper half is missing. Nevertheless, it is clear that it is a battle against an enemy without a fortified town. We can deduce this from the position of pharaoh’s horse and chariot team. Egyptian battle scenes follow a standard compositional sequence, and this scene falls into the genre type of battle scene without an enemy fortress.9 (Incidentally, the inscriptions, rather than the scenes, give the depictions their individual identity and historical context.)10

The fourth battle scene in the wall can be usefully contrasted with the relief of the siege of Ashkelon. In the latter, pharaoh’s horse and chariot on the right are balanced by a carving of the fort of Ashkelon on the left, with a siege ladder resting against the wall and two children being let down from the wall. In the fourth battle scene, by contrast, although only half of it is preserved, we see pharaoh’s horse and chariot team directly in the center of the picture. There is no balancing enemy fortress at the left, nor could there be even in the missing upper half of the scene, for there would simply be no room for it before the front hooves of pharaoh’s charging chariot team. In contrast to the other three battle scenes, this scene depicts a battle with an enemy in open country with low hills.

This battle scene matches the description of Israel in the Merenptah Stele text, where it is written  (Ysr3l), with the determinative

(Ysr3l), with the determinative  signifying a people without a city-state, as contrasted with the names for Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am, all three of which are written with the determinative

signifying a people without a city-state, as contrasted with the names for Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am, all three of which are written with the determinative  or

or  , signifying a specific city-state. The other three battle reliefs on the Karnak temple all have fortresses that are besieged by the king, the first of which is specifically identified as the town of Ashkelon. So there is a perfect match between the text of Merenptah’s Stele and Merenptah’s reliefs. Ashkelon, Gezer, Yano‘am and Israel, named in the stele, match three fortified towns and one battle in open country in the reliefs.

, signifying a specific city-state. The other three battle reliefs on the Karnak temple all have fortresses that are besieged by the king, the first of which is specifically identified as the town of Ashkelon. So there is a perfect match between the text of Merenptah’s Stele and Merenptah’s reliefs. Ashkelon, Gezer, Yano‘am and Israel, named in the stele, match three fortified towns and one battle in open country in the reliefs.

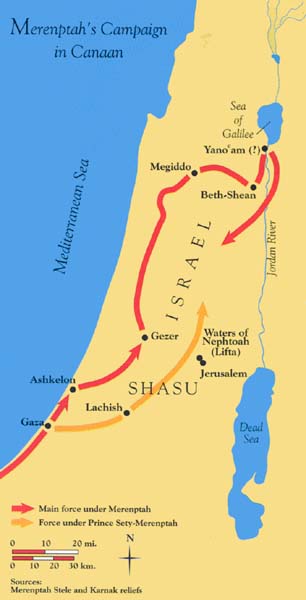

If you look at Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am on a map, you will see that they lie on a south-to-north progression from the coastal plain into the hill country, where the Israelites lived (although the site of Yano‘am is a matter of some dispute). This parallels the whole narrative sequence of Merenptah’s Karnak reliefs, for Ashkelon is shown in the first scene, two other cities in the next scenes (which I propose are Gezer and Yano‘am) and an open battle in low hills in the last scene (which I propose is Israel). This same sequence of scenes—from right to left in the bottom register, followed by left to right in the top register—is attested elsewhere in New Kingdom narrative relief.11

It seems clear that Merenptah originally had these reliefs commissioned and carved to represent and commemorate his Canaanite campaign as described retrospectively in the Merenptah Stele!

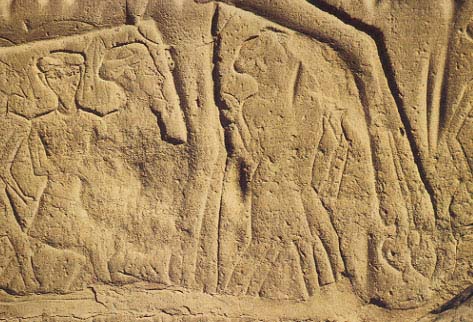

If I am correct, then the enemy men depicted in the fourth battle scene are Israelites! These depictions are by far the earliest visual portrayals of Israelites ever discovered, dating to the late 13th century B.C.E. The next time we see Israelites in a visual depiction is over 600 years later, on the wall of Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh, where reliefs depict the siege and conquest of the Israelite city of Lachish, with the defeated Israelites being executed, or led to exile in Assyria.f

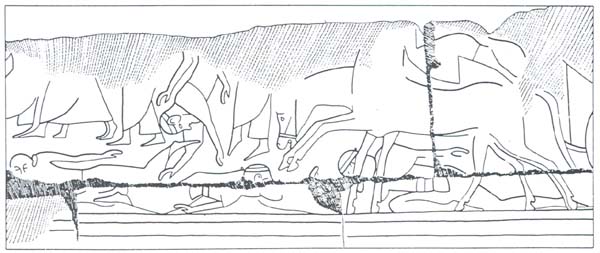

The most significant aspect of the depiction of the Israelites in the battle scene at Karnak is that they wear the same style of dress as Canaanites in the scenes of Ashkelon, Gezer and Yano‘am. The Israelites are wearing ankle-length cloaks, just like the Canaanites. In short, the Israelites are identified pictorially as Canaanites in the Merenptah reliefs and textually as Israel in the Merenptah Stele. This may well have considerable historical significance, especially because the Canaanite—and therefore the Israelite—dress is distinctly different from the dress of the people known as Shasu, often associated with Israelite origins, who are also depicted in the Merenptah reliefs on the wall of the Karnak temple, but not in the battle scenes.

The Shasu are traditional Bedouin-type foes of Egypt. In one well-known papyrus, Papyrus Anastasi 1, Shasu are reported as being found all over Canaan, but particularly in the forested and wild hill-country.12 In Merenptah’s reign, as we know from another papyrus (Papyrus Anastasi VI), Shasu were found in southern Canaan and in Sinai. This papyrus is a frontier official’s journal mentioning a peaceful migration of Shasu shepherds into the Delta for the purpose of watering their flocks.13

As they were wont to do, some others of these Shasu undoubtedly harried Merenptah’s army as it was en route to subdue the Canaanite cities and Israel. They were defeated, of course, and some were captured, as we are told in the hieroglyphic text. In the carvings, we see Shasu prisoners in some of the reliefs to the right of the battle scenes on the Karnak temple wall. In scene 5 we see enemy Shasu being bound. Scene 7 depicts a file of Shasu prisoners being marched off to Egypt before and under pharaoh in his chariot. A vertical line of text separates scene 7 from scene 8 and translates in the surviving part, “rebels who had fallen to trespassing his boundary.” In scene 8 another file of Shasu are depicted, above them a horizontal line of text reading “consisting of the Shasu whom his majesty had plundered.” Above this text, just enough of the block remains to show that here was a file of Canaanite prisoners, readily distinguishable from the Shasu by their long, ankle-length cloaks. The Shasu, by contrast, wear short kilts and distinctive turban-style headdresses.

The Shasu were not the major focus of Merenptah’s campaign in Canaan, and so they were given a secondary representation in the Karnak reliefs of the campaign, and they are not referred to at all in the Merenptah Stele.

According to some scholars, the Shasu formed the core of the people who became Israelites when they settled in the hill country of Canaan beginning in the late 13th to the 12th centuries B.C.E. The evidence from the Karnak reliefs contradicts the position taken by scholars who have tried to identify the Israelites with the Shasu.14 The Karnak temple reliefs seem to suggest that at least some of the early Israelites coalesced out of Canaanite society, albeit Canaanites who did not live in the cities but who had withdrawn to the hill country, precisely where archaeological remains as well as Biblical texts place them.g

The attribution of these battle reliefs at Karnak to Merenptah puts Merenptah’s campaign into Canaan on a firm historical footing. Moreover, the reliefs provide striking confirmation of accumulating archaeological evidence that the initial Israelite settlements were in the highlands and that they were in open, dispersed villages with no substantial fortified towns. Nonetheless the Israelites had already begun to disturb the settled towns under Egyptian suzerainty, and thus provoked a response from Merenptah. Whereas Egyptian control of the highlands was previously limited, this time Merenptah penetrated the hill country in force and there found the settlements of the Israelites. Judging by the name he recorded for them on the Merenptah Stele, they were already calling themselves Israel in about 1211 to 1209 B.C.E., the time frame of Merenptah’s Canaanite campaign. This is the first extra-Biblical use of the name Israel.

A small detail suggests that the Israelites had been attacking the settled towns. In the scene representing the battle with the Israelites, there appears a chariot with wheels with six spokes that belongs to the pharaoh’s enemy, that is, Israel! How could the early Israelites have gotten possession of chariots, once thought to be the exclusive possession of Israel’s enemies such as the Canaanites? (In Judges 4–5, for example—which records a battle involving Jabin, king of Canaan; Sisera, his general; and the Israelite prophetess Deborah, who defeated the Canaanites—the Canaanites have all the chariots.) Perhaps the Israelites got chariots like the one depicted in their battle with Merenptah by raids on Canaanite towns. However, it is also possible they got them through an alliance with some of the Canaanite towns that Merenptah attacked or that feared such an attack.

These battle reliefs not only corroborate the historicity of Merenptah’s campaign into Canaan, but they also shed some light on the precise date of that campaign. Scholars have of course considered these questions on the basis of the Merenptah Stele alone, and, as I have said, have raised some questions as to whether the campaign actually took place. The passage referring to Merenptah’s campaign in Canaan is at the very end of the text, in the poetic conclusion of the stele. That this conclusion is so carefully laid out and very precisely arranged geographically also supports the conclusion that the text indeed has a historical basis. The outer verses refer to the broader international situation involving Libya (Tehenu) and the Hittite empire (Hatti). The inner verses balance a description of Canaan and Hurru, the two major components of Egypt’s Syro-Palestinian realm.15 The text for Canaan is further broken down into the three city-states and Israel. So, the breakdown neatly delimits the area of Merenptah’s military activity—it is all within Canaan. Finally, Canaan and Hurru are poetically couched in terms of husband and wife. Such careful and neat geographical structure does not usually appear in fictional military campaigns.

The Merenptah Stele also contains a date for the inscription of the stele, the fifth year of Merenptah’s reign. Merenptah ruled between 1212 and 1202 B.C.E., so his campaign into Canaan must have occurred between 1212 and 1207 B.C.E., the latter being the date of the Merenptah Stele.

Remember that the main subject of the Merenptah Stele is the Libyan campaign and his battle with the Sea Peoples. His Canaanite campaign is mentioned in the stele only retrospectively. This Libyan campaign too must have occurred by 1207 B.C.E. This campaign is also commemorated on a wall of the Karnak temple, but only with a long text and a triumphal scene,16 and even these appear on an interior wall. War scenes generally occupied external walls of temples. The reason Merenptah’s important Libyan campaign is depicted only with a triumphal scene and even this only on an interior wall, despite the fact that the Libyan campaign was a far more momentous victory than his Canaanite campaign, is that Merenptah had already used the last exterior space of the temple for the scenes of his Canaanite campaign. This confirms that the Canaanite campaign occurred before year five of his reign. In a lengthy, technical discussion based on a change in Merenptah’s prenomen, I have excluded year one of Merenptah for this Canaanite campaign.17 In another somewhat technical paper,18 I concluded that the Canaanite campaign took place in year two, or early in year three. Briefly, no document of Merenptah dated year two or early year three demands his presence inside Egypt in that time span, so those are the narrowest limits within which the campaign may presently be dated. This corresponds to 1211–1209 B.C.E., and this therefore marks the first attested date for Israel outside the Biblical record.

To judge by his mummy, Merenptah was between 60 and 70 years old when he organized and led his Canaanite campaign and organized the defense of Egypt against the Libyans and the Sea Peoples in his fifth year.19 Professor Donald Redford, of the University of Toronto, has belittled Merenptah’s ability to lead a campaign of any importance into Canaan in his supposedly “decrepit”20 condition. This argument is nothing short of ridiculous considering that Merenptah, even after his Canaanite campaign, organized Egypt’s defense against Nubian, Libyan and Sea Peoples onslaughts in his fifth year. As to the age issue, General Douglas MacArthur was 70 years old when he led the attack on Inchon in Korea in 1950. Moreover, like MacArthur, Merenptah was a military man and a general.

It is true that Merenptah’s mummy shows us an individual who was in poor physical condition at death. Yet that was five years after the Nubian, Libyan and Sea Peoples defensive operation, and seven to eight years after the Canaanite campaign.

After Merenptah’s death, in 1202 B.C.E., competing branches of the royal family engaged in a bitter struggle for the throne. All the usurpation of cartouches and titularies in the reliefs is symptomatic of the struggle for the throne between different branches of the descendants of Ramesses II. This usurpation occurred not only in the reliefs we have been discussing, but also elsewhere in the Cour de la Cachette and in the entire temple of Karnak.21

Nevertheless, Egypt’s control over Canaan, apparently solidified by Merenptah’s campaign, seems, if anything, to have tightened rather than slackened between Merenptah’s time and the reign of Ramesses III (1182–1151 B.C.E.) of the XXth Dynasty. Under Ramesses III, tax collection was instituted and substantial administrative centers were built at a number of locations.22

In addition, artifacts bearing the names of Merenptah or his successors in the XIXth Dynasty have been discovered in numerous excavations of Canaanite sites, providing further testimony of undisputed Egyptian control strengthened by Merenptah’s campaign. Gezer23 and possibly Lachish24 have yielded objects naming Merengtah. At Gezer, a destruction level dated to Late Bronze II B (1300–1200 B.C.E.) probably is the work of Merenptah’s campaign.25 Sety II’s name is attested at Tell el-Fara (South),26 at Tell Beit Mirsim27 and possibly at Tel Masos.28 The names of other Egyptian rulers from this time are attested at Acco,29 Beth Shemesh30 and Deir ‘Alla (Jordan).31

In addition, a papyrus (Papyrus Anastasi III) dated to Merenptah’s third year32 shows the Egyptians in possession of strategic places in the highlands of Canaan very shortly after the Canaanite campaign.

All of this suggests the following scenario: By this campaign, Merenptah reaffirmed Egyptian dominion over the Canaanite coastal towns and northern Canaan. His Transjordanian vassals, previously conquered by Ramesses II,33 did not invite attack and so probably remained loyal. The chief trouble was found to be in the hill country west of the Jordan, where the Israelites had been settling in considerable numbers.34 Very probably enboldened by the long period of quiet and absence of military activity that marked the last phase of Ramesses II’s reign, some of these Israelites, now coalescing into a group identifying itself as Israel, attempted to penetrate into the lowlands held by Canaanite vassals of pharaoh.35 Some of these vassals may have thrown their lot in with the Israelites, even enabling the Israelites to get some chariots. Pharaoh Merengrah, however, was not willing to let Canaan slip away, so that after he had dealt with the rebelling vassals on the coast and inland, he turned to the hill country and dealt a heavy blow to the Israelites.

The defeat must have been quite heavy to emerging Israel, for the Israelites could not take advantage of the struggle between Merenptah’s successors. Ramesses III then imposed a tight Egyptian hold on Canaan, which was not broken until Sea Peoples (including Philistines) settling in Canaan weakened the Egyptian hold sufficiently for the Israelites to begin to overcome the Canaanite strongholds. But this occurred only in the 12th century B.C.E., after the death of Ramesses III (1151 B.C.E.). Merenptah thus delayed Israel’s emergence onto the lowland areas for at least a generation.

One final note: There may be a garbled reference to Merenptah’s Canaanite campaign in the Bible itself. Joshua 15–19 records the allotment of the land to the various tribes. In Joshua 15:9, the border of Judah near Jerusalem is drawn from a hilltop at the northern end of the Valley of Rephaim to “the spring of the waters of Nephtoah” and then goes on to the cities of Ephraim. In Joshua 18:15, the southern boundary of Benjamin is drawn west from Kiriath-jearim “to the spring of the waters of Nephtoah.” These Hebrew passages probably refer to a well, or spring, at Lifta near Jerusalem.

It is possible that Nephtoah in both of these Biblical references is actually a garbled version of Merenptah’s name. Papyrus Anastasi III, which I mentioned above, dates from Merenptah’s third year and describes the Egyptians as possessing strategic places in the highlands of Canaan; it also tells of the arrival of a military commander at Sile, coming from “the Wells of Merenptah-hotphima‘e which are in the hills.”36

The spring referred to in Joshua 15 and 19 is probably the same place: The Egyptian papyrus indicates there was a place in the highlands of Canaan that included the name Merenptah. Is the spring of Nephtoah, as referred to in Joshua, the same as the Well of Merenptah in the Egyptian papyrus? Remember, Merenptah is written in consonants, as is the Hebrew text. In the equivalent in Latin letters, Merenptah would be spelled MRNPTH; Nephtoah would be spelled N(PH)TH. The signs P and PH are identical in Hebrew. So the only difference in the two names is that the MR seemingly has dropped out of the Hebrew.37 In the Hebrew Biblical text, “spring of the waters” is redundant. “Waters” in the Hebrew text is MY, but if this was originally MR, it would supply the missing letters of Merenptah’s name and the Hebrew text would no longer be redundant; it would read simply the “Spring of Merenptah.” Indeed, such naming of geographical features for the currently ruling pharaoh was a common practice in Ramesside Egypt.

If MY Nephtoah is indeed a garbled form of Merenptah, then we have further corroborating evidence from the Bible regarding the presence of Israelites in Canaan during Merenptah’s reign.

Thus, in the last decade of the 13th century B.C.E., some of the Israelites in the highlands were already using the name Israel to designate their premonarchic tribal confederacy. This usage is its earliest occurrence and appears again only in the Song of Deborah (Judges 5), which scholars now date some three-quarters of a century after Merenptah.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

B.C.E. (Before the Common Era) and C.E. (Common Era) are the scholarly alternate designations corresponding to B.C. and A.D.

This name is often written “Merneptah.” The hieroglyphic signs do not indicate vowels, so either vocalization is possible. The name means Beloved of Ptah. The sign for “of” is the hieroglyphic equivalent of n. I believe it much more likely that it was read en, rather than ne.

See Kenneth Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant (see endnote 5) pp. 215, 220 and fig. 70. In a recent article, Donald B. Redford (“The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stele” [see endnote 141, pp. 188–200) tried to return to the older viewpoint by claiming that the usurped cartouches on this wall were unreadable, and that the pharaoh’s chariot team names are the same as those used by Ramesses II. Both of these arguments and others he poses are based on inadequate study of the reliefs and Ramesside sources in general, and on a serious underestimate of epigraphic work; moreover, the usurpation sequence on this wall in some cartouches is unambiguous (for example, in scene 2). See further, my response to Redford, in Yurco “Once Again, Merenptah’s Battle Reliefs at Karnak,” IEJ, forthcoming.

See Joseph A. Callaway, “Sir Flinders Petrie: Father of Palestinian Archaeology,” BAR 06:06.

The poetical versification is my own, with the advice of Dr. Edward F. Wente of the University of Chicago.

See Hershel Shanks, “Destruction of Judean Fortress Portrayed in Dramatic Eighth-Century B.C. Pictures,” BAR 10:02.

Endnotes

The reliefs I will be discussing are located on the transverse northsouth axis of the Karnak temple on the outer western face of the court between the Hypostyle Hali and the Seventh Pylon, known as the Cour de la Cachette.

Francoise Le Saout, “Reconstitution des Murs de la Cour de la Cachette,” Cahiers de Karnak 7 (1978–1981), pp. 228–232, and pl. IV on p. 262.

Adapted from Frank J. Yurco “Merenptah’s Canaanite Campaign,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt (JARCE) 23 (1986), p. 197 (fig. 10).

Another important element in the earlier attribution of all the reliefs on this wall to Ramesses II is the presence of a Prince Kha-em-Wast in one of the later battle reliefs to the left of the Peace Treaty text (scene 2)—for Ramesses II had a very famous son of that name. However, the Prince Kha-em-Wast shown in this scene is not the well-known son of Ramesses II, but a like-named son of Merenptah. Formerly Kenneth A. Kitchen took the Kha-em-Wast of these reliefs to be a son of Ramesses II (“Some New Light on the Asiatic Wars of Ramesses II,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 50 [1964], p. 68, n. 9, and Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical [Oxford: Blackwell, 1973-present] [hereafter KRI], vol. 2, p. 165, notes 4a-b); but since hearing my paper in Toronto in November 1977, he has accepted my position that Kha-em-Wast is indeed a son of Merenptah (see Kitchen: KRI, vol. 4, p. 82, no. 49 n. B, and Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses I [Mississauga, Ont., Can.: Benben Publ, 1982], pp. 215–216 and fig. 17 on p. 220). Additional evidence supports this identification: in scene 2, Prince Kha-em-Wast is a military personage, while Ramesses IIs’ like-named son was high priest of Ptah for much of his career. Further as shown by Eugene Cruz-Uribe (“On the Wife of Merenptah,” Göttinger Miszellen 24 [1977], pp. 24–25), Merenptah’s chief queen, Isis-nofret II, was a daughter of the high priest of Ptah, Kha-em-Wast I, and a granddaughter of Ramesses II. In the Ramesside royal family, it was very common practice to name grandchildren after their grandparents, and this is precisely what Merenptah seems to have done in the case of Kha-em-Wast II.

For example, E.A. Wallis Budge, A History of Egypt (New York: Oxford Univ., Henry Frowde, 1902), vol. 5, pp. 103–108; John A. Wilson, The Burden of Egypt (Chicago Univ. of Chicago Press, 1951), pp. 254–255, Wilson, “Hymn of Victory of Mer-ne-Ptah (The ‘Israel Stele’),” in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET) with supplement, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 3rd ed., 1969), pp. 376–378, esp. p. 376; Pierre Montet, Lives of the Pharaohs (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968) pp. 198–200; and Montet, Egypt and the Bible, transl. Leslie R. Keylock (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968), pp. 25–26.

Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, p. I, line 9 w‘f K3d3r. Scholars supporting the historicity of the texts include W.F. Flinders Petrie, A History of Egypt (London: Methuen, 1905), vol. 3, p. 114; Eduard Meyer, Geschichte der Altertums (Stuttgart and Berlin: J.G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, 1928), vol. 2, pp. 577–578; James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1912), pp. 465–466, and Sir Alan H. Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1961) p. 273.

For a similar scene in complete form, see Herbert Ricke, George R. Hughes and Edward F. Wente, The Beit el-Wali Temple of Ramesses I, Oriental Institute Nubian Expedition, vol. I (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1967), pls. 7–8.

See Alexander Badawy, A History of Egyptian Architecture: The Empire (the New Kingdom) (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1968), pp. 448–474 for a discussion of fortress types found in Egyptian reliefs and their patterning on actual buildings.

G.A. Gaballa, Narrative in Egyptian Art (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1976), pp. 100–104; applicable to battle reliefs and prisoner collecting scenes. But for Prince Kha-em-Wast II in scene 2, Kitchen would already have identified these battle reliefs with the texts on the Cairo stela no. 34025 and its fragmentary duplicate from Karnak, as he clearly had noted the usurped cartouches while collecting the texts of the scenes for his monumental KRI publications (“Some New Light on the Asiatic Wars,” p. 48, n. 1, and p. 68, n. 9).

Wilson, “An Egyptian Letter,” ANET, pp. 475–479; from the place names within the text, it dates to the reign of Ramesses II. The Shasu are described on pp. 477–478.

Papyrus Anastasi VI. See Ricardo A. Caminos, Late Egyptian Miscellanies (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1954), p. 293; Wilson, “The Report of a Frontier Official,” ANET, p. 259.

For example, Raphael Giveon, Les Bédouins Shosou des documents egyptiens Documenta et Monumenta Orientis Antiqui, vol. 18 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1971), pp. 267–271, Manfred Weippert, “Canaan, Conquest and Settlement of,” in Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible Supplement (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1976), p. 129; Wieppert, “The Israelite ‘Conquest’ and the Evidence from Transjordan,” in Symposia Celebrating the Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the American Schools of Oriental Research (1900–1975), ed. Frank Moore Cross, (Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1979), pp. 32–34; Donald Redford, “The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stele,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) 36 (1986), pp. 199–200; Redford’s assumption that the Shasu in the Merenptah reliefs are the Israelites because Israel is not named elsewhere in the reliefs ignores the battle relief in scene 4, where the top is lost. His glib assertion that all the other names on the reliefs (except the Shasu) are also found on the Israel stele overlooks the plain evidence from the walls—only Ashkelon, in scene 4, is named; the fortresses in scenes 2 and 3 are unnamed, Yurco, “Merenptah’s Palestinian Campaign,” pp. 196 and 199–201; Kitchen, KRI, vol. 2, p. 165, lines 4–7. This position, again taken by Israel Finkelstein, “Searching for Israelite Origins,” BAR 14:05, uncritically following Redford, and without reference to either my paper (“Merenptah’s Palestinian Campaign”) or to that of Lawrence Stager, “Merenptah, Israel and Sea Peoples: New Light on an Old Relief,” Eretz Israel 18 (1985), pp. 56–64. From Papyrus Anastasi I (Wilson, “An Egyptian Letter,” ANET, p. 476), where the Shasu are described as uttering Semitic phrases as they furtively watch an Egyptian divisional camp, one may conclude that like other Canaanites the Shasu were Semitic peoples; it is not impossible that they were related to the Israelites, but Merenptah’s reliefs, particularly scene 4 of the battle reliefs, make it quite clear that the Shasu were not Israelites.

In Merenptah’s reign, Gaza, capital of Canaan, was called Gdt (Gaza) and not Pa-Canaan, as in some other reigns. See Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Onomastica, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press 1977), vol. I, p. 191, no. 624; and Caminos, Late Egyptian Miscellanies, pp. 108–110 (Papyrus Anastasi III, verso 6, 1 and 6, 6).

6 Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, pp. 2–12; and Kitchen and Gaballa, “Ramesside Varia II,” Zeitschrift für Agyptische Sprache 96 (1969), pp. 23, 25, 27, and table 8, also, Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, pp. 23–24.

Under Merenptah, the Sea Peoples attacked from the west, and did not settle in Canaan. See Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant, p. 215; see also Itamar Singer, “The Beginning of Philistine Settlement in Canaan and the Northern Boundary of Philistia,” Tel Aviv 12 (1985) pp. 111–114.

See Yurco, “Amenmesse: Six Statues at Karnak,” pp. 15–31; and Cardon, “An Egypt-Royal Head of the Nineteenth Dynasty in the Metropolitan Museum,” pp. 5–14.

Eliezer D. Oren, “‘Governors’ Residences’ in Canann under the New Kingdom: A Case Study of Egyptian Administration,” Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities (JSSEA) 14, no. 2 (March, 1984), pp. 37–56.

Ivory sundial, see Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, p. 24, no. 7B; R.A.S. MacAlister, The Excavation at Gezer (London: John Murray, 1912), vol. I, p. 15 and vol. 2, p. 331, fig. 456 (described as a pectoral). First identified as a sundial by E.J. Pilcher, “Portable Sundial from Gezer,” Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement (1923), pp. 8589. See also Singer, “An Egyptian ‘Governor’s Residency’ at Gezer,” Tel Aviv 13 (1986), pp. 26–31.

Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, p. 37, no. 17 (bowl), dated year 4, king unnamed. Merenptah has been proposed as the pharaoh under whom this bowl was inscribed partly based upon another similar bowl dated year 10 (or higher?), Mordechai Gilula “An Inscription in Egyptian Hieratic from Lachish,” Tel Aviv 3 (1916), pp. 107–108, also Redford “Egypt & Asia in the New Kingdom: Some Historical Notes,” JSSEA 10, no. I (December, 1978), pp. 66–67. This dating, however, has been challenged by Orly Goldwasser (“The Lachish Hieratic Bowl Once Again,” Tel Aviv 9 [1982] pp. 137–138), who would read the texts in a different order and date them to Ramesses III. As the bowl’s texts concern tax collection Ramesses III seems the probable date. Regardless of this problem with the dating of the bowls, Lachish remained firmly in Egyptian control at least into Ramesses III’s reign; see also David Ussishkin, “Lachish—Key to the Israelite Conquest of Canaan,” BAR 13:01.

Stager, “Merenptah, Israel, and Sea Peoples,” p. 62, n. 2, William G. Dever et al., “Gezer II: Report of the 1967–70 Seasons in Fields I and II,” Annual of the Hebrew Union College Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), p. 52 and n. 26. See also, Singer, “An Egyptian ‘Governor’s Residency’ at Gezer,” pp. 26.

Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, p. 242, no. 1, inscribed jar fragments, see Eann MacDonald, J. L. Starkey and G.L. Harding, Beth Pelet II, British School of Archaeology, vol. 52 (London: British School of Archaeology and Bernard Quaritch, 1932), pp. 28–29, and pls. 61, no. 3, and 64, no. 74.

Trude Dothan, The Philistines and Their Material Culture (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1982), p. 43 and n. 109.

Scarab: Giveon, “A Monogram Scarab from Tel Masos,” Tel Aviv I (1974), pp. 75–76; another from Tel Taanach, now in the Dayan Collection, p. 76 and n. 3; also Giveon, “The Impact of Egypt on Canaan,” Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, vol. 20 (Freiburg: Universitats Verlag, 1978), pp. 107–109, and fig. 58b.

Scarab: Kitchen KRI, vol. 4, p. 341 no. 1 Alan Rowe, Catalogue of Scarabs, Scaraboids, and Amulets in the Palestine Archaeological Museum (Cairo: Institut francais d’archeologie orientale, 1936), p. 164, no. 690, and pl. 18.

Kitchen, KRI, vol. 4, p. 341 no. I, and p. 351, no. 17 (faience vessel naming Tawosret, misident;fied as Ramesses II), in H.J. Franken “The Excavations at Deir ‘Alla in Jordan,” Vetus Testamentum (VT) 11 (1961), p. 385, and pls. 4–5. Correctly read as Tawosret by Jean Yoyotte, “Un Souvenir du ‘Pharaon’ Taousert en Jordanie,” VT 12 (1962), pp. 464–469.

Papyrus Anastasi III, verso 6, 4 to 6, 6. Caminos, Late Epyptian Miscellanies, p. 108; and Wilson, “Journal of a Frontier Official,” ANET, p. 258 and n. 6.

Stager, “Merenptah, Israel and Sea Peoples,” pp. 60–62; Stager, “The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research 260 (1985), pp. 1–24.

Yohanan Aharoni, The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography (Philadelphia, Westminster, 2nd ed., 1979) pp. 183–184, 195 and 218–220. Contra Aharoni, the Israelites did not conquer Lachish at the end of the XIXth Dynasty, see note 24 above.

Caminos, Late Egyptian Miscellanies, p. 108, and Wilson, “Journal of a Frontier Official,” ANET p. 258 and n. 6.

and

and  of Amenmesse’s nomen can be seen in the extant cartouche, the former just above the

of Amenmesse’s nomen can be seen in the extant cartouche, the former just above the  of Sety II’s nomen, and the latter to the left of the

of Sety II’s nomen, and the latter to the left of the  of Merenptah’s nomen.

of Merenptah’s nomen. from the upper portion of his nomen. From Merenptah’s prenomen, the legs of the

from the upper portion of his nomen. From Merenptah’s prenomen, the legs of the  clearly remain below the

clearly remain below the  from Sety II’s prenomen.

from Sety II’s prenomen.