Against All Odds: Elie Borowski Builds His Museum

Neither inflation, nor intifada, nor the unwillingness of others to share his dream could stop this man.

046

Elie Borowski impatiently thrusts aside questions about the cost of the Jerusalem Bible Lands Museum that will open on May 10, 1992. “It is unholy to the mission to speak about money. Just say it is nes min hashamayim (a miracle from heaven). Right away, from its opening, it will be one of the great museums of the world.”

Later in our conversation he returns, on his terms, to the value of his extraordinary collection and to the cost of the magnificent museum that now houses it. Seventy-eight-year-old Borowski rumbles to a crescendo over the transatlantic phone line: “I was a failed philologist, a failed Talmudist; I failed as a rabbi and as a professor, but I did not fail as an art dealer. I made big, big, big, big money. But instead of building an empire of oil or an empire of banks or of real estate, I built an empire of mishegoss.” Borowski, born in Poland and nurtured in his early years to be a great rabbi and scholar, uses the Yiddish word that carries the notion of a crazy obsession.

The exquisite museum, nestled on the same hillside in Jerusalem as the sprawling Israel Museum, houses Elie Borowski’s obsession—a collection of more than 3,000 artifacts, gathered lovingly by him, one by one, to illustrate or to confirm events and peoples mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

While the nearby Israel Museum displays chiefly archaeological finds from Israel, Borowski’s Bible Lands Museum concentrates on the ancient peoples surrounding the land of Israel—their gods and goddesses, customs, iconography and art, and craftsmanship. From Afghanistan in the east to the Mediterranean in the west to the Caucasian mountains in the north to Nubia in the south, Borowski’s Bible Lands collection was accumulated by him while he made his fortune buying and selling art and artifacts that came onto the European market during the turmoil immediately after World War II. Still today the Bible Lands collection grows.

It required an obsession to make this museum happen—an obsession and a wife named Batya, 16 years his junior, whom Elie married in 1982. Batya brought to Elie her own consuming dream for his collection—that it be housed in Jerusalem, her first and beloved home. When they married, the Bible Lands collection was slated to become part of the holdings of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto where the Borowskis lived. But the pieces languished in storerooms of the ROM, and it became clear that nothing would happen in Toronto.

Batya negotiated with Mayor Teddy Kollek to have the collection permanently housed in Jerusalem. The city provided a beautiful site on a hillside, near the Israel Museum. The rest was up to the Borowskis.

In an interview with BAR editor Hershel Shanks in late 1984, Elie spoke angrily: “Is it not enough that I give my collection? Shouldn’t others give now? If the world is not willing to give a home to this collection, the world does not deserve it.”a

Despite Elie’s thundering challenge, the world responded with deafening silence. Very soon it became clear that either the Borowskis must raise this building or it would never happen.

To start construction, Borowski made the first of two agonizing decisions to part with a precious piece from his collection. He sold to the Minneapolis Institute of Art one of his treasures—the magnificent, larger-than-life-size marble Doryphoros, the spear bearer—the finest of five extant Roman copies of a long-lost bronze masterpiece by the fifth-century B.C.E. Greek sculptor Polykleitos. Elie 047describes the Doryphoros as the “torah” of ancient sculpture, called by art historians the “canon” because it established the Greek norm for perfect proportion and balance.

The $2.5 million, paid by the Minneapolis Institute in 1985 for the Doryphoros, had been negotiated between Borowski and the Institute five years earlier. While the Institute raised the money, the value of the Doryphoros more than doubled. Elie stood by his agreement. Today he shrugs off compliments with some bitter words about the Institute’s windfall.

But now all that is past. The Polykleitos sale marked the beginning of construction of the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem (BLMJ). For two years construction proceeded until, in 1987, a triple blow fell. Johns Hopkins University, which had pledged $7 million to enlarge the original design of the museum to house and organize a graduate study center, pulled out totally, with the expansion already substantially under construction but not finished. At the end of the year the recession struck, sending the value of the dollar plummeting in European markets and costs spiraling for European steel, windows and other major items needed for the museum. And on December 9 the intifada ignited. In the months ahead Arab laborers on the construction crews often failed to turn up for work.

“We were stranded high and dry,” Batya recalls. “Construction stood still for two years. We hired fundraisers, but the only money they raised was from Borowski.” “People found it difficult,” Batya admits, “to conceive of this museum.”

Time weighed heavily on the Borowskis. Elie was well into his seventies. Batya said, “I wanted Elie to have the pleasure of being part of what he created.” They realized the museum would never be completed unless Elie did it himself; he would have to sacrifice another piece from his collection. Elie sold a precious artifact to a Japanese collector. He won’t disclose what the piece was, for how much he sold it or to whom. “It was heartbreaking,” he repeats several times, because, unlike the magnificent Doryphoros, this artifact would have become, he says, an extremely important part of the Bible Lands Collection.

048

But the doors of the Bible Lands Museum will open on May 10, and that is more important than any single piece. Planned in 1985 to cost $3 million and to be completed in two years, the museum will open six-and-a-half years later in a structure that cost $12 million—99 percent of it from the Borowskis.

The doors will open into a space created to emphasize continuities and connections among the cultures of the ancient Near East. The exhibition space, all on one level, is divided by low walls so that the eye can travel forward and backward in time as one follows what exhibit designer Clifford LaFontaine calls “a continuous trek.” Unlike so many of the other great museums in the world where he has designed exhibits, LaFontaine says that the BLMJ is not meant to show how distinct and unique a piece may be—how Assyrian, how Egyptian, how Babylonian—but rather to show the ways that piece is linked in time and space to other cultures in the region and to the Bible.

Cases will have relevant quotations from the Bible, but these are not intended to imply that the objects come from the exact time of the Bible, or that they mention Biblical characters or Bible stories. In fact, for many of the artifacts displayed the date or provenance can never be known with certainty. They are uprooted pieces, discovered by people whose intention was to sell, not to scientifically study and record. Dating and locating is accomplished by putting together all the clues: information gathered from the seller, analysis of iconography, craft techniques and epigraphy and comparison with similar artifacts. By this means artifacts are assigned a time and place.

Like a complicated musical score, subthemes interweave the museum’s main themes of chronology, geography and the Bible. Recurrent subthemes relate to technological inventions and their development: metalworking, pottery, toolmaking, preliterate and literate communication, the invention of writing. Other subthemes relate to warfare, temple architecture, local and provincial gods, economics and culture.

For the first time, Elie Borowski says with pride, artifacts bearing the names of all the gods in the pantheons of Egypt, Sumer and Babylonia will be displayed in one place. Other artifacts contain the most complete collection of names that the Bible uses to speak of the Hebrew God, including El, Elohim, Adonai (the pronunciation of the tetragrammaton, yod hay vov hay) and Tsur (meaning literally, in Hebrew, the Rock).

One exceptional exhibit will be a clay tablet recounting the daily ritual of a Babylonian temple from the 15th until the 24th month of Shvat, called Shabatu in the Babylonian calendar. Dating from the time of Abraham, this tablet comes from the city of Larsa, under whose dominion was Ur of the Chaldees, Abraham’s birthplace. It describes the observance of the 15th of Shabatu, corresponding to Tu b’shvat,b the Jewish festival of the New Year for planting trees, and thus sheds light on the pivotal importance of Tu b’shvat in ancient days. This is the exact date mentioned in the Mishnah, the 049early third-century codification of Jewish oral law, almost 2,000 years later. The 15th of the lunar month is the day of the full moon on which most Jewish holidays occur. The Babylonian system of demarcating years and months was adopted by the Jews during their Babylonian exile. The Biblical evidence demonstrates the day started at sunset in Israel and the BLMJ tablet proves that the Babylonian day also started at sunset and ended at sunset the next day.

When the museum opens, its chief curator, Dr. Joan Goodnick Westenholz, plans to make it a study center for students and teachers from Israel and abroad. Public symposia, traveling exhibits, teaching videos and interactive computers for visitors to ask and learn, relationships with overseas institutions—all are part of the BLMJ’s future.

Who will shoulder the operating expenses of the BLMJ? Almost single-handedly the Borowskis built and furnished it. But to operate the museum Benjamin Abileah, former consul general of Israel in Toronto and now director of the BLMJ, expects to rely on income from admissions, corporate sponsorship, membership, donations, endowment he hopes to raise and the gift shop and cafeteria. Elie Borowski adds two more sources of support: “God’s will and Elie’s brain” and a passionate determination that the Bible Lands Museum will flourish in lasting memory of his family, who perished in the Holocaust.

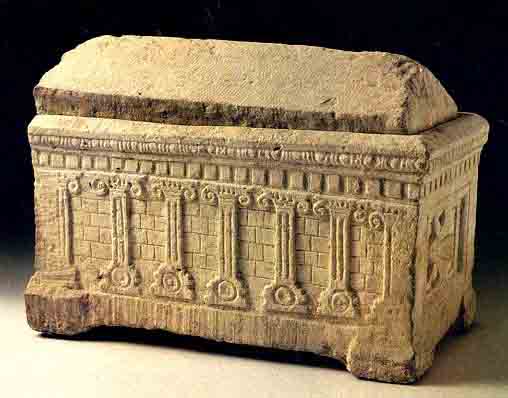

Inthis article, we present a gallery of artifacts from the Bible Lands Museum collection. Were Elie Borowski to stand at your side, he would explain these pieces with his special fervor and encyclopedic knowledge of the art and cultures of the ancient Near East. He would point out their beauty, their significance for understanding the Bible and the uniqueness of each piece he carefully selected—some more than 40 years ago—and held until the day it could be seen by the world in its own magnificent museum.

The Borowskis invite everyone who will be in Jerusalem May 10–13 to attend the events of the opening of the BLMJ. For information about registration, gala dinners and tours write: Bible Lands Museum, Fox Tours, 27 Route 46 West, Suite D-107, Fairfield NJ 07006, Attn. Drora Katz or phone toll free: 1–800-257–1706.

Elie Borowski impatiently thrusts aside questions about the cost of the Jerusalem Bible Lands Museum that will open on May 10, 1992. “It is unholy to the mission to speak about money. Just say it is nes min hashamayim (a miracle from heaven). Right away, from its opening, it will be one of the great museums of the world.” Later in our conversation he returns, on his terms, to the value of his extraordinary collection and to the cost of the magnificent museum that now houses it. Seventy-eight-year-old Borowski rumbles to a crescendo over the transatlantic phone line: “I […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Elie Borowski Seeks a Home for His Collection,” BAR 11:02, and “Treasures from the Lands of the Bible,” BAR 11:02.