016

Taking a short passage from the Bible and looking at it from a variety of perspectives can be very instructive. For example, from a short passage from the book of the eighth-century B.C. prophet Amos, we can learn: something about the problems of translation and why scholars sometimes emend (that is, change) the text; how a knowledge of everyday life in Bible times and of earlier pre-Israelite cultures help illuminate the text; something about the nature of the prophetic calling; and finally, a little about how to interpret the prophetic message—as one of hope rather than doom.

The short passage on which I will focus—Amos 7:1–9, 8:1–3—contains four prophetic visions (see the sidebar to this article).

What we commonly refer to as a vision is the prophet’s experience of the imminent presence of God. Sometimes, but not always, the vision constitutes the prophet’s call to prophetic activity. The visions in Amos 7 and 8 came to the prophet after he had been active for some time.

Visions that come to the prophets from time to time often occasion an influx of important ideas and powerful emotions that give new meaning and direction to an understanding of God’s intent for Israel and its people.

All four visions in Amos 7 and 8 are first person reports, a typical form of autobiographical memorabilia. They all begin the same way: “This is what Yahweh showed me”; the beginnings tie the visions together and also set them apart from surrounding material. The visions are succinct, using an economy of language. They exhibit elevated, finely polished prose.

Looking at the visions more closely, we see that there are two pairs, the first two and the last two. In the first pair Amos initiates the dialogue. In the second pair it is Yahweh who initiates the dialogue. In the first pair of visions, dangers to Israel’s future are averted by Amos’s intercession. Here we see a significant, though often overlooked, role of the prophet—as intercessor. A prophet not only speaks to the people on behalf of God; he also speaks to God on behalf of the people. In the first pair of visions, God relents.

The thrust of the second pair of visions is precisely opposite from that of the first. In visions three and four, Amos does not intercede. Not only does he not intercede, but the destruction of Israel is presented as certain.

A Vision of a Swarm of Locusts (Amos 7:1–3)

In the first vision, the farmers of Israel are threatened by a swarm of locusts Yahweh is creating. Locusts come in huge clouds that blacken the sky as though the sun were setting. They are capable of destroying all vegetation (compare Isaiah 33:4).

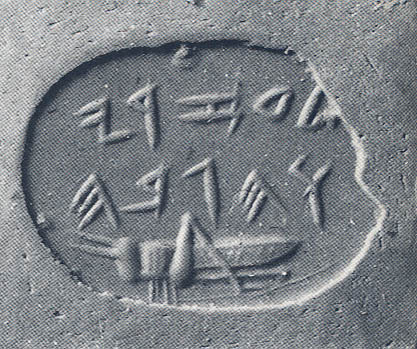

A late eighth-century B.C. seal containing a 017Hebrew inscription (the owner’s name) and an extremely well-executed locust lends immediacy to our perception of this biblical menace. Somehow we better appreciate the threat of the locust when we see such a vivid, almost contemporaneous portrayal. The Hebrew word for locust used in Amos’s vision is gby; the customary word for locust, however, is ’rbh. In only one other passage in the Bible is a variant of gby used (Nahum 3:17). This seal, however, uses another variant of gby (that is, gbh). The Picture on the seal establishes that the word gbh on the seal means locust. Apparently this was the seal owner’s family name. This may be the only instance in Hebrew epigraphy where a name is accompanied on a seal by a pictorial illustration of its meaning. The owner of the seal would certainly have been surprised if he had known that 2,700 years after he used the seal it would help confirm “locust” as the meaning of an unusual biblical word.

Most scholars believe that the last line of the first verse in this vision— “Lo, it was the late sowing after the king’s cutting.” —was a notation made in the margin of an Amos manuscript at a later date. This line emphasizes the catastrophic nature of the locust threat in this vision. In the ancient Near East two crops were grown in one season. The first paid the royal tax; the second, usually less Productive, crop was retained by the farmer. In the vision, it was the second crop that the locusts were to devour.

Amos understood the vision of the locusts devouring the crops as having a deeper meaning. It was a symbol of the destruction of the nation. Therefore, he pleaded with God not to visit this dreadful catastrophe on the people. Jacob (a synonym for Israel), the prophet tells God, is small and not able to withstand God’s judgment. In response to Amos’s intercession, Yahweh is moved to pity. The calamity that was about to befall the nation is averted.

A Vision of a Rain of Fire (Amos 7:4–6)

The second vision follows the same pattern as the first. It too concerns a great catastrophe, the means by which Yahweh would punish the nation. The subject—“rain of fire”—suggests that an experience of lightning prompted the vision.

The Hebrew phrase I have translated “he was calling for a rain of fire” is usually translated “he was calling for a judgment by fire” (see, for example, the Revised Standard Version). Literally, it means “he called to contend by fire” (see the New Jewish Publication Society translation). Actually neither the RSV nor the NJPS translation makes much sense. My translation, “rain of fire,” depends on a different word division of the text 019than the standard word division. In ancient manuscripts, the scribe often failed to provide any indication, by space or otherwise, of where one word ended and the next one began. The spaces between the words of the Bible were provided only hundreds of years after the text was written. The standard word division, as I have indicated, yields “contend by fire,” which doesn’t make sense. The standard Hebrew word division is as follows:

The threat here is that the fire will consume the “great deep.” In earlier Near Eastern mythology the “great deep” referred to the mythological monster Tiamat, goddess of the deep whom Marduk slew in the Babylonian creation epic. In Canaanite literature found at Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit, on the Syrian coast, north of Israel) we meet a minor deity with a double name —dbb

The prophet uses what was originally mythological language, but in a historicized way. In the passage in Amos, the fire will consume not only the great deep, but the land as well. The picture we get is of a great fire drying up the subterranean waters that ultimately provided the springs that irrigate the farmlands. If Yahweh rained down this fire, it would eventually dry up the fathomless waters of the deep that fed the springs and would consume the entire land.

Amos again intercedes, reminding God of Israel’s weakness and vulnerability. Again Yahweh, portrayed as displaying a sensitivity to the needs of his people and with an emotional awareness of the outcome of his actions, becomes personally involved in the lives of humanity and responds favorably: “It won’t happen.”

A Vision of Tin (Amos 7:7–9)

In traditional translations, the vision in 7:7–9 refers to a plumb line or plumb bob. The line I have rendered, “Lo, someone stood beside the 020heat holding tin in his hand” is usually translated something like this: “Behold, the Lord was standing beside a wall with a plumb line” (RSV).

The crux in the passage is the Hebrew word ’

The common translation “beside a wall built with a plumb line” is recognized by most commentators as an impossible translation. The New Jewish Publication Society translation candidly confesses that the “meaning of [the] Heb[rew] is uncertain.”

The literal meaning of the Hebrew is that the wall is made out of material represented by the word ’

What, then, is the meaning of “tin” in the vision? If we turn to the fourth vision, with which this vision is paired, we note that there also the prophet sees something. The word for what he sees reminds him of another word similar to it in sound. It is this word that conveys the meaning of the vision. So also in this third vision. The word for tin—’

Yahweh then makes clear what will happen in Israel. No longer will any of their worship centers, the “high places” situated on hills taken over from the Canaanites, or sanctuary buildings, remain in use. In addition the house of Jeroboam (Jeroboam II, c. 786–747 B.C.) will come to an end. In fact, Jeroboam’s dynasty ended about 747 B.C. with the assassination of Jeroboam’s son, 021Zechariah, after a reign of six months.

In this vision, Amos does not intercede. There appears to be no reprieve.

There is a break between the third and fourth visions. Following the third vision, with its reference to King Jeroboam, there is a prose biographical unit written no doubt by a contemporary of Amos. Its purpose is to add a historical statement regarding what happened to Amos. Its placement at this point in the text is according to what scholars call the catchword principle. That is, the word Jeroboam in Amos 7:9 occasioned the placement of 7:10–17 because of the word Jeroboam in 7:10.

A Vision of Ripe Fruit (Amos 8:1–3)

The fourth vision (Amos 8:1–3) concerns a basket of ripe fruit. The word for ripe fruit is

But the word

The word “end” has unmistakable eschatological overtones. This is prophetic, not apocalyptic, eschatology—not the final end of the world or time, but the end of Israel as a this-world, this-history event after which there will be a new this-world, this-history Israel. In apocalyptic eschatology, by contrast, the end is final, and after there is only an other-world existence.

Although the idea of a renewed Israel is not conveyed in this vision, we find it at the very heart of Amos’s prophesies, including the famous passage with which the Book of Amos ends:

11On that day,

I will restore David’s fallen Succoth;

I will block up the gaps in its wall;

Its ruins I will restore,

Rebuilding it as in former days.

12[That they may possess the rest of Edom and all the nations that once were mine—Oracle of Yahweh who does this.]

13Yet, the time will soon come

[—Oracle of Yahweh—]

When the plower will overtake the reaper,

And the vintager the sower;

When the juice of grapes will run down the mountains

And all the hills shall flow with it.

14I will restore the fortunes of my people Israel.

They will rebuild deserted cities and settle down.

They will plant vineyards and drink wine.

They will make gardens and eat the produce.

15And I will establish them upon their land.

They will never again be uprooted from their land.

[Which I have given them] Says Yahweh your God.

Amos 9:11–15 (author’s translation)

In the fourth vision, Israel’s demise is emphasized by the statement, “Never again will I pardon her,” a repeat from the third vision, which thus ties the third and fourth visions together. There follows in the fourth vision the statement, “The palace singers will wail that day.” The Hebrew literally says, “Songs will wail,” so the text is usually emended to

The fourth vision closes with a single word,

Some scholars deny that any hope is conveyed by Amos himself. I disagree. The first two visions do present a message of hope, which is repeated at the end of the book, as quoted above. Yahweh is presented as a God who listens to the voice of the prophet when forbearance and forgiveness are called for. Yahweh is a God of salvation.

Taking a short passage from the Bible and looking at it from a variety of perspectives can be very instructive. For example, from a short passage from the book of the eighth-century B.C. prophet Amos, we can learn: something about the problems of translation and why scholars sometimes emend (that is, change) the text; how a knowledge of everyday life in Bible times and of earlier pre-Israelite cultures help illuminate the text; something about the nature of the prophetic calling; and finally, a little about how to interpret the prophetic message—as one of hope rather than doom. The short […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

See Delbert R. Hillers, “Amos 7:4 and Ancient Parallels,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 26 (1964), pp. 221–225.

Benno Landsberger, “Tin and Lead: The Adventures of Two Vocables,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24 (1965), pp. 285–296.