026

The Roman poet Ovid, in Metamorphosis (10:298–518), relates a story that sensitively reflects much about one of the best-known aromatic substances in the ancient world, myrrh.

In the story, Myrrha, the beautiful daughter of the king of Cyprus, falls in love with her father. She disguises herself and proceeds to seduce him. When the king discovers what his daughter has done, he decides he must kill her. Frightened, Myrrha flees, asking the gods for protection. The gods transform her into a myrrh tree; in that way she escapes and avoids being killed. She is pregnant, however. Accordingly, nine months later, the bark of the myrrh tree cracks, giving birth to her child, who is none other than the god Adonis. Water nymphs care for the child, anointing him with Myrrha’s tears.

There is reason to believe that this myth ultimately has its roots in the ancient Near East, although its ancestor has not yet been found. In the myth, Myrrha represents myrrh, an aromatic substance that comes from South Arabia. Adonis is the Greek counterpart of the Mesopotamian god Tammuz,1 the well-known ancient Near Eastern deity of spring vegetation, who is mentioned in the Bible: In Ezekiel 8:14, the prophet has a vision in which he sees women weeping for Tammuz at the gate of the Temple.

This myth, like so many others, is subtly instructive if we read it perceptively. Myrrh, we learn, is connected with seduction, with love, with death, with divinity and is used even as medicine. Myrrh is used to seduce, to persuade in order to obtain what is otherwise forbidden. Myrrha escapes being killed by being transformed into a myrrh tree; this is, in effect, her death, which warrants the 027use of myrrh at funerals. The gods’ care of Myrrha makes myrrh a substance under divine protection, in fact divine substance. Myrrha’s son is anointed with his mother’s tears; these tears are the subtle image of the drops of the sap of the myrrh tree. The anointing of Adonis with myrrh reflects the medical use of myrrh and at the same time a religious ritual.

In its own symbolic way, the myth tells the story of myrrh, reflecting its use in connection with lovemaking, danger, mourning and death.

We can demonstrate these connections from the literature of the ancient Near East (including the Bible), as well as from archaeology. Myrrh is one of many aromatic substances sometimes grouped under the heading incense, although incense—etymologically the word is related to incendiary—strictly speaking involves burning of the aromatic substance to intensify the odor. Other aromatic substances include frankincense, aloes, cinnamon, cassia, sweet-smelling cane, storax, cress, galbanum, gum and labdanum. Simply by way of illustration, we will look at some uses of myrrh in connection with lovemaking, danger, mourning and death.

In the middle of the second millennium B.C., Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt anointed herself with stacte, a perfume made from myrrh.2 Myrrh’s ethereal odor makes it perfect for use in perfumes.

In the book of Esther (2:12), Esther anoints herself with myrrh oil for six months before being presented to the king.

The Song of Songs begins:

“Oh, give me the kisses of your mouth,

For your love is more delightful than wine

Your ointments yield a sweet fragrance.”

Then in Song of Songs 1:13:

“My beloved to me is a bag of myrrh

028

Lodged between my breasts.”

The myth of the birth of Adonis accurately reflects the use of myrrh in lovemaking.

In dangerous situations—that is, when struck by disease—myrrh was used as a medicine in both Egypt and Canaan. In the famous Amarna tablets, diplomatic correspondence inscribed in cuneiform characters on clay tablets found in Egypt, a foreign monarch asks pharaoh to send him myrrh “as a medicine.”3 If the Egyptian word ‘ntyw is indeed myrrh, as many contend, myrrh is frequently found in Egyptian medicinal recipes.4 Even today myrrh is used in many unguents, where it acts as a disinfectant and contractant.

Myrrh was also used in connection with mourning and death. In a Phoenician sarcophagus inscription from the sixth or fifth century B.C., the deceased person is said to lie in myrrh and bdellium.5 In Egypt, various aromata, undoubtedly including myrrh, were used for embalming the dead. In John 19:39–40, we are told that Jesus’ body was anointed with myrrh and aloe.

Myrrh and other aromatic substances were also widely used (and continue to be so used) in religious rituals, largely in the form of incense. Ancient Israelite rituals were no exception. The use of incense in religious rituals is obviously related to the psychological reaction of human beings to different kinds of odors. Some odors are pleasant, others are decidedly unpleasant. Myrrh and other aromatic substances have the power to transform bad odors into good odors.

Bad odors signal danger. Bad smells are associated with death and decay, putrefaction and disease. Such smells induce fear. The natural reaction is to take precaution against the evil caused by these odors.

Death, a daily occurrence, causes fear in its own right. This fear is augmented by the fact that the dead person’s body soon begins to smell badly. The use of incense alleviates the bad odor.

The use of aromatics was probably first incorporated into religious rituals relating to death. Since incense can eliminate the odor of death, it took on a purifying quality. It purified the dead person and, in a mystic way, transformed the dead person’s state of death and steady decay into a state of preservation. Indeed, the use of incense at funerals seems ultimately to be based on the belief that the dead person somehow is alive despite the presence of all the signs of death. In my opinion, the belief in the ability of incense to reverse the decree of death is the most primal reason or its widespread use in religious ritual. (It is no accident that the earliest references to incense are found in Egyptian pyramid texts dealing with the dead pharaoh.)6

Bad smells, however, also reach the human nose at quite another level, a less dangerous, but still annoying, level: as perspiration. Humans have always exuded unpleasant odors. It was early discovered that incense as a perfume could help do away with this problem. Unlike the smell of death, the smell of perspiration is neither crucial nor immediately dangerous. Therefore, unlike death, perspiration does not call for a religious reaction in the form of a ritual. Perspiration calls for private hygiene, with various aromatic substances used for anointing or fumigating the body, according to taste. Thus, aromatic substances were used in both secular and religious contexts, with the important difference that the secular context did not require the substances to be handled by a priest in a ritually fixed fashion.

Contrary to what we might expect, incense is rarely mentioned in the Bible in connection with death, mourning or funerals. What was so common in Egypt seems to have been uncommon in Israel. 030Jacob, who died in Egypt, was embalmed (Genesis 50:2). Incense substances of various kinds may have been used in that connection. Joseph too died in Egypt and was embalmed (Genesis 50:26). But the practice of embalming never spread to Canaan or to the Israelites generally. This was probably because the Israelites did not share the elaborate Egyptian belief in afterlife.

The only reference to spices and aromata in connection with an Israelite funeral is in a relatively late composition. It appears in 2 Chronicles 16:14, where the funeral of King Asa (911–869 B.C.) of Judah is described: “They laid him on a bier that had been filled with various kinds of spices prepared by the perfumer’s art; they made a very great fire in his honor.” Whether this fire was used to burn some of the spices is difficult to tell.

In Jeremiah 34:5, the prophet prophesies in the name of the Lord and tells King Zedekiah (597–586 B.C.) of Judah: “You shall die in peace. And as spices were burned for your fathers, the former kings who were before you, so men shall burn spices for you and lament.” This seems to indicate that a ritual involving the burning of incense at royal funerals may have been customary in ancient Israel.

Among the Israelites, however, the ritual use of incense was primarily found in the Temple cult. Yet the Bible does not contain a story that explains or legitimates the use of incense in that regard. The Bible simply prescribes its use without directly telling us why or what the origins of the prescription are.

Circumstantial evidence indicates that, in the eyes of his own worshippers, the God of the Hebrews was able to smell, to use his nostrils, in contradistinction to the pagan idols, who “have mouths but do not speak, eyes but do not see; they have ears but do not hear, noses but do not smell” (Psalms 115:5–6).

To take another example in contrast to these pagan idols: When Noah built an altar after the Flood and made a burnt offering to the Lord, “the Lord smelled the pleasing odor … ” (Genesis 8:21; compare Leviticus 26:31, where the Lord tells the Israelites that if they do not walk in his ways, he “will not smell your pleasing odors”; see also Amos 5:21 in the King James Version).

Apparently, under the right conditions, the Lord simply liked pleasing odors; at least this appears to be the only mythological basis for the ritual use of incense among the Israelites.

According to the Bible, a compound aromatic ointment was used to sanctify and consecrate the wilderness tabernacle (and by implication the Temple) with all its furniture and vessels, as well as the priests themselves:

“Moreover, the Lord said to Moses, ‘Take the finest spices: of liquid myrrh five hundred shekels, and of sweet-smelling cinnamon half as much, that is, two hundred and fifty, and of aromatic cane two hundred and fifty, and of cassia five hundred, according to the shekel of the sanctuary, and of olive oil a hin’ ” (Exodus 30:22–24).

With this holy ointment, objects and persons were purified before participating in the daily worship.

The Bible further relates that a special gold-plated altar was fashioned to burn incense in the Temple (Exodus 30:1–5). Incense was to be burnt on it every morning and every evening (Exodus 30:7–8). This daily, or regular, incense offering is called tamid in Hebrew. What was the purpose of the tamid? Since 031the Bible does not tell us, we have to guess. The principal idea may have been to purify the room for the presence of the Lord. The room was thus consecrated to the divine presence; purification and consecration go hand in hand. Another reason for this burning may have been to induce the divine presence to remain. In Egyptian mythology, the gods left their temples at night and had to be called back in the morning. Incense rituals were often used in Egypt to attract the gods, to induce them to return. Since the Israelite God did not leave his Temple at night, perhaps incense was used to induce him to remain there.

The incense altar described in Exodus had horns at the corners (Exodus 30:2). Small altars, with and without horns at the four corners, have been found at various sites in Israel—at Megiddo, Mizpah, Shechem, Gezer, Arad and Hazor. They range in date from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.) to the Persian period (late sixth-fifth centuries B.C.). These altars are made of stone, while the biblical incense altar was made of wood covered with gold. Otherwise, in size and outer appearance, they resemble the incense altar described in the Bible. On the other hand, from the archaeological evidence alone, it is difficult to identify these altars purely as incense altars. Other offerings, such as grain, may have been burnt on them.

Incense was also used in connection with other offerings. For example, frankincense was added to certain meal offerings (Leviticus 2:1–3, 2:14–16, 6:14–18 [verses 7–11 in Hebrew]). In the Temple, frankincense was also sprinkled over the shewbread placed on the table before the Lord (Leviticus 24:5–9).

The part of the meal offering that is burnt on the altar of burnt offerings with the frankincense is called an ‘azkarah, as is the frankincense of the shewbread. The word ‘azkarah may provide the clue to the purpose of burning incense in these cases. The word is probably derived from the root ZKR, which means, among other things, “to call upon the name of a deity” (compare the Akkadian zakaru). In other words, burning incense produced a soothing odor, pleasing to the deity, thus attracting and appeasing the deity at one and the same time.

For the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), Leviticus 16 prescribes a special ritual that expiates the sins of everyone—Aaron, the high priest; his family; and, finally, the community of Israel. It is on this day alone that the high priest stands before the ark. Among other things, the ritual prescribes that the high priest put some glowing coals into a

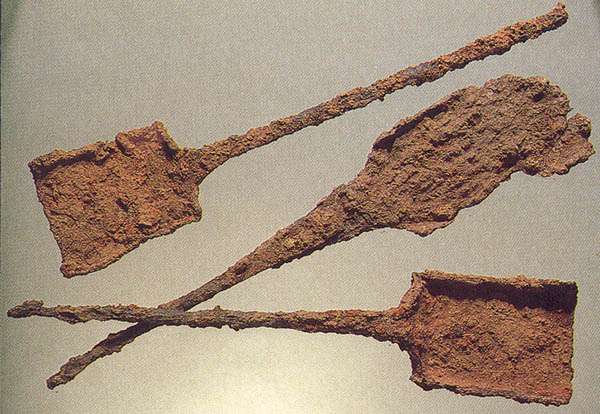

Incidentally, this ritual for the Day of Atonement is the only instance in the entire Bible in which a shovel or firepan is prescribed as a censer to hold the burning coals that ignite the incense. An obscure story in Leviticus 10:1–3 records the death of Nadab and Abihu, the two sons of the high priest Aaron. Each of the sons “took his

This latter possibility is suggested by way of an analogy to another well-known incident involving censers—the Korah rebellion against the authority of Moses and Aaron (Numbers 16; in Hebrew, Numbers 16–17). The Korahites rebelled because, according to them, “all the congregation was holy,” not just Moses and the priests of Aaron. Moses told the rebels to prepare 250 firepans (

The bronze firepans of these Korahites were then hammered into plates to cover the altar, to serve as a sign to the Israelites— “to be a reminder to the people of Israel, so that no one who is not a priest, who is not of the descendants of Aaron, should draw near to burn incense before the Lord” (Numbers 16:40; in Hebrew, Numbers 17:5).

The very next day other Israelites took up the Korahites’ cry, as a result of which the Lord brought a plague upon the people. Moses, wanting to protect the people from the plague, instructed Aaron to take his

These incidents make it clear that the burning of incense was a priestly prerogative. After the Korah rebellion, incense burning comes under the exclusive control of the Aaronite priesthood. When this actually occurred, we cannot tell, but the story is clearly intended to validate this priestly prerogative. This incident also exhibits the apotropaic, or evil-averting, qualities of incense. Incense may also be seen as having purifying characteristics—it atones for sin.

That the burning of incense in the Temple is a priestly prerogative is confirmed in the story of King Uzziah recorded in 2 Chronicles 26:16–21. Uzziah entered the Temple to burn incense to the Lord, but was stopped by the priests. Uzziah grew angry at them for stopping him and immediately broke out with leprosy, 033from which he suffered for the rest of his life.

Uzziah was carrying a censer called a

Ritual use of incense was widespread in Egypt and Mesopotamia, both in the home and at religious centers. In Israel, however, ritual use of incense was limited to the official worship in the Temple in Jerusalem. Just as Israel limited the use of incense in this way, it also limited the tools used in connection with the use of incense, to the exclusion of the

Because of these uses of incense throughout the ancient Near East, aromatics were a highly valued and important item of commerce and international trade. In Genesis 37:25 we read that Joseph’s brothers meet an Ishmaelite caravan carrying three kinds of aromata from Gilead to Egypt. The aromata the caravan carries—tragacanth gum, storax and labdanum—all come from Syria-Palestine. The Egyptians could use all the incense they could obtain.

A special compound of incense that included frankincense was used in the Jerusalem Temple (Exodus 30:34–38). Frankincense comes from South Arabia. Recent excavations in Jerusalem discovered two potsherds with South Arabian inscriptions dating to the seventh to sixth centuries B.C.7 They were probably brought here by South Arabian traders, who may have carried frankincense and myrrh with them.

What appear to be small incense altars have been found in Israel as well as in Egypt, South Arabia and Mesopotamia. Similarities among them reflect cultural connections. Small cuboid altars uncovered at Lachish, Gezer and elsewhere, dating from the seventh century B.C. to Hellenistic times ultimately seem to drive from South Arabia, where similar specimens have been found with the names of aromata inscribed on them.8 Unfortunately the archeological data do not tell us who used these little burners or for what purpose.9 The same is true of other kinds of censers dating from the third millennium on. The population of the ancient land of Israel was mixed, and there were many different cults and religions. A vessel found in an Israelite stratum may have been used by a non-Israelite and vice versa.

Finally, the value of incense is reflected in the nativity story in Matthew. The three wise men from the East present the holy child with “treasures,” among which are frankincense and myrrh (Matthew 2:11).

The Bible is not a handbook of rituals. It does not provide us with all the details involved in the rituals where incense plays a part. It has not preserved a funeral ritual at all; it has not preserved a complete Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) ritual. There are many more details we would like to know.

Nor does the Bible tell us why incense was used. We are left to guess—based on the general cultural setting and the general Near Eastern background.

The archaeological—that is, nontextual—material concerning incense and incense-burning in the land of Israel gives us a rather confused picture. For instance, we learn that incense was burned in censers and on altars in temples dating to the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.) and Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.), when Canaanite city-states flourished. Later, in Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.), the burning of incense, especially in censers but also on altars, increased in private houses. This was at a time when national states like Israel, Edom and Moab were established.10

Our textual evidence—that is, the Bible—is not a history book any more than it is a handbook of rituals. It does not simply mirror historical reality. Instead, it tries to form historical reality according to the ideals of the Jerusalem priesthood, which produced the Bible as we know it. The priests tried to limit the ritual burning of incense to the Jerusalem Temple and tried to limit the types of incense altars and burners that could be used legitimately in Israelite worship. All this must be deduced from the biblical evidence. But, in the end, taking all the evidence together, we get a reasonably clear picture.

The Roman poet Ovid, in Metamorphosis (10:298–518), relates a story that sensitively reflects much about one of the best-known aromatic substances in the ancient world, myrrh. In the story, Myrrha, the beautiful daughter of the king of Cyprus, falls in love with her father. She disguises herself and proceeds to seduce him. When the king discovers what his daughter has done, he decides he must kill her. Frightened, Myrrha flees, asking the gods for protection. The gods transform her into a myrrh tree; in that way she escapes and avoids being killed. She is pregnant, however. Accordingly, nine months […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “BAR Interview: Avraham Biran—Twenty Years of Digging at Tel Dan,” BAR 13:04.

Endnotes

As for the connection between Adonis and Tammuz, see W.W.G. Baudissin, Adonis und Esmun (Leipzig: J.C. Henrichs, 1911) pp. 352–371.

See Raymond O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1969). The texts date from the Vth and VIth Dynasties, the second half of the third millennium B.C. See Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1964), p. 87.

Yigal Shiloh, “South Arabian Inscriptions from the City of David, Jerusalem,” Palestinian Exploration Quarterly (PEQ) 119 (1987), pp. 9–18.

See M.D. Fowler, “Excavated Incense Burners: A Case For Identifying a Site as Sacred?” PEQ 117 (1985), pp. 25–29.