Ancient Churches in the Holy Land

027

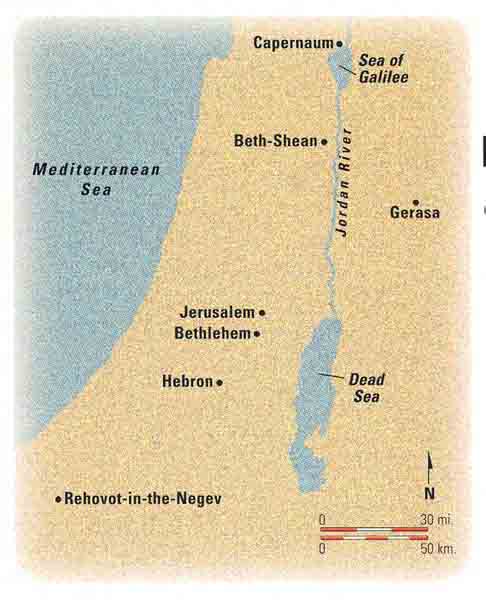

More ancient churches have been found in the Holy Land than in any area of comparable size in the world. About 330 different sites with ancient church remains have been identified in modern Israel, the West Bank and the Golan Heights east of the Sea of Galilee. At many of these sites, more than one ancient church stood. At Madaba in Transjordan (not included in our survey area), 14 turned up. In Jerusalem there were several dozen churches and chapels. In all, about 390 ancient churches at these 330 sites have been discovered.

Almost none, however, are earlier than the Byzantine period (324–640 C.E.). For our purposes, the Byzantine period in Israelinspired church begins in 324 C.E., when Constantine, the first Christian emperor, conquered the East. Two years later, his pious mother, Helena, made her pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which resulted in the discovery of Jesus’ tomb and Constantine’s initiative in building the first Byzantine churches. The Byzantine period ends in Israel with the Arab conquest of Palestine (630–640 C.E.).

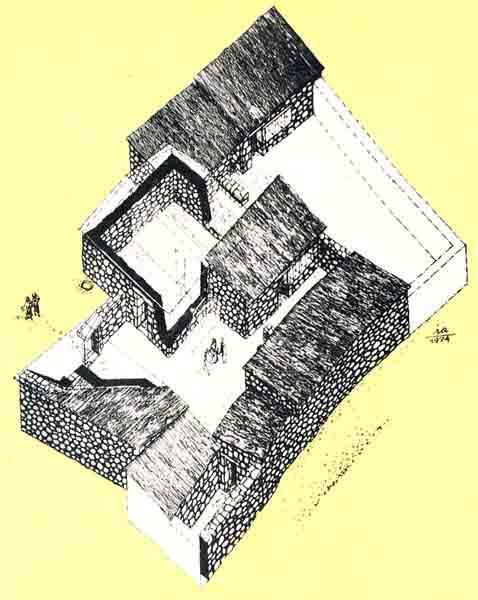

Before the Byzantine period, Christians met and worshiped in private houses. Such a building was known as a domus ecclesia (house-church). In the fifth century, 028an octagonal church, still known as St. Peter’s House, was built in Capernaum over a structure that began, according to its excavator Virgilio Corbo, in the Roman period as a private house and was later converted to a house-church where early Christian pilgrims gathered and left their graffiti on the replastered walls for 20th-century archaeologists to discover.a

But, in general, house-churches are very difficult to identify because they are indistinguishable from other domestic structures. They were not only modest in size but rather few in number.

With the accession of Constantine, Christianity throughout the Roman world underwent a dramatic change. This was especially true in Palestine, which saw one of the greatest cultural transformations in its history as Christianity triumphed over paganism.

The road to establishing Christianity in the Holy Land was long and difficult. It began in the time of Jesus and the apostles, who struggled with both the monarchy and with the pagan, Jewish and Samaritan inhabitants of the land. Once Christianity became the official religion of the empire, in about 392, however, it spread at an accelerated pace, uninterrupted until the Arab conquest.

Byzantine culture was an amalgam of Roman tradition, Hellenistic-Greek civilization and Christianity. The first two elements derived from the past and represented continuity. Christianity, however, was a revolutionary innovation. It transformed Roman society beyond recognition.

Although the entire empire was slowly Christianized, the imperial court accorded an especially high priority to Christianizing the Holy Land. There the Christian Messiah had been born and had died; there many of the loca sancta, or holy places, were to be found.

Byzantine architects generally continued the work of their Roman predecessors. But, instead of secular architecture, they devoted their energies and powers of invention to designing impressive, ornate churches.

The Christian church building is the creation of the early fourth century. Before that, as we have already noted, Christian communities assembled for worship in private, rather than public, buildings. The domus ecclesia comprised a large room for prayer, rituals and communal meals (agape) and other rooms for storage and services. Sometimes there was a separate baptisterium as well as a room where candidates for baptism (catechumeni) assembled. By contrast, the Byzantine churches from the fourth century on were public structures built specifically for Christian observance.

Generally Byzantine churches can be divided into two categories—the basilica and the central plan. The large majority of these churches, both early and late, are of the basilical type.

The basilica church consists of a long, rectangular central hall divided by two (or four) longitudinal rows of columns, creating a central nave and two (or four) side aisles. A wide, high doorway opened onto the nave; doorways to the aisles were generally smaller.

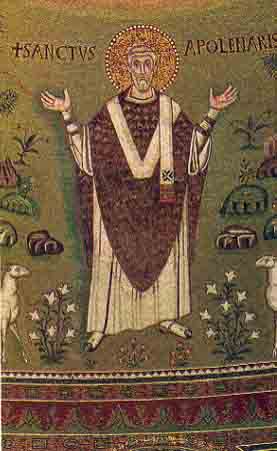

At one end of the nave, in most cases in the east (where the sun rises), was the chancel, or bimah, also called the presbytery (priests’ place). This was largely contained in an apse in the eastern wall covered with a half dome that was usually decorated with frescoes or mosaics featuring the figure of Jesus. That part of the church—the sanctuary—was restricted to the priests. From the chancel a narrow flight of stairs led up to the ambo, or pulpit for delivering sermons, which was situated within the nave, usually near one of the columns.

The roof of the basilica church was gabled, generally supported with triangular wooden trusses and surfaced on the outside with tiles. The trusses were supported by both the outer walls and the columns in the hall so that the part over the central section was considerably higher than that over the sides.

The pavements were usually laid with mosaics, although these were inferior to marble-colored stone plaques (opus sectile). The walls were, in many cases, coated with frescoes or wall mosaics.

The architectural source of the Christian basilica was the multipurpose Roman civic building of the same name, found in public places, within sacred compounds and in private palaces. ‘Fine most common type of Roman basilica was the basilica of the forum, which, after the temple, was the major public building in Roman cities. In the Roman civic basilica, 030the raised apse held a statue of a god or the emperor. It was also the place from which orators delivered speeches and magistrates adjudicated business disputes.

It was quite natural that the Christian architects at the time of Constantine adopted the Roman basilica as their religious building. The Christian church, like its predecessor, the Jewish synagogue, was intended for public use, in contrast to the pagan temple, where the worshipers were restricted to the temenos (the temple’s holy enclosure) outside. The spacious basilica thus offered a practical solution to the physical needs of the congregation. By choosing the basilica and not the temple form, the Christians also emphasized the distinction between their religious practices and those of paganism.

The architectural changes in the basilica necessary for Christian worship were few, but they had a powerful effect on the final character of the building. The Christians made the chancel and apse deeper, with the entrance to the church on the opposite wall. Thus, the colonnaded, static interior of the Roman basilica was transformed into an elongated space drawing the visitor inward. From the moment believers entered the church, their eyes and hearts were directed toward the apse and the altar.

In detail as well as in overall design, these churches reflected Christianity’s triumph. When Constantine became the patron of the Christian faith and elevated it to an official, honored status, the heads of the Church were obliged to adopt trappings befitting the imperial religion. The emperor encouraged the bishops to decorate their religious edifices to the same extent as the pagans had embellished theirs. It was a significant step in the struggle for the soul of the masses, who hesitated between the new religion and the traditional cults.

Although the early Christians had been comfortable with the modest domus ecclesia and its atmosphere of intimate fraternity and humility, values in the time of Constantine changed: There was a desire to absorb the 032masses into the Christian community and to impress them by royal splendor no less than by spirituality. The interior of the church was decorated lavishly with carved columns and capitals, mosaics and wall paintings, expensive building materials, and gold chandeliers. The priests wore elaborate liturgical vestments. The shadowy interior of the building, with burning candles and incense, gave the finishing touches to an atmosphere of mystery that is characteristic of Christian worship.

In contrast, the exterior of the church, although elegant, was relatively modest. It suited the traditional Christian value of shunning wealth and ostentatious display. This marked contrast between the exterior and the interior of the structure is representative of the introspection emphasized in Christianity, which its architects sought to reflect.

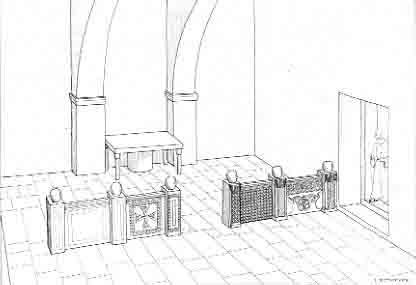

The Eucharist, the main part of the Christian liturgy, was celebrated by the priests before the altar, in the apse. The main hall was divided from the chancel by a low screen. Many of these chancel screens have survived. They were made of a series of limestone or marble panels connected by limestone or marble posts into which the panels were inserted. The panels were usually carved in low relief or in a lacework fashion.

In the main hall, the male and female congregants were probably separated, the men on one side and the women on the other.

The basilica was complemented by auxiliary rooms and wings, some of which were part of the original building and others added later: the prothesis, the chamber in which the bread and wine were prepared for the Eucharist; various chapels; the baptisterium; and the diaconicon, the storage room for ritual objects and donations from the congregation.

Other optional architectural elements included the narthex, a broad corridor built in front of the church at the facade of the main hall, and the atrium, a courtyard usually completely or partially enclosed by porticoes, which provided an appropriate introduction to the church building itself.

Many basilica churches were resplendent with holy relics, such as tombs of, or the remains of, early Christian martyrs. The tombs, whether or not of genuine martyrs, were sometimes located in underground chapels, or crypts, beneath the chancel and altar.

Other holy relics were actual objects, such as a piece of the True Cross, a stone from Golgotha or 034one from the stoning of St. Stephen the martyr. Smaller relics were placed in special reliquary boxes, deposited in the apse, beneath the altar or in one of the side rooms.

From the beginning, a special form of church evolved that was architecturally more suitable for commemorative purposes than the basilica. The commemorative church emphasized its center. It could be circular, octagonal, square or cruciform. In contrast to the basilica, the centric plan was not based on the apse at the end of the building, but rather on the geometrical center of the church, which was further accentuated by the height of its dome or by the apex of its conical roof. In this way, a kind of elaborate raised canopy was created, epitomizing the holy place below it.

These centric-plan churches were, in the main, inspired by monumental tombs (mausolea) of emperors and patricians of Rome. But they also recall other monumental Roman buildings, both secular structures (such as round chambers, roofed garden pavilions of palaces or bathhouses) and religious structures (round temples like the Pantheon in Rome).

Used in commemorative locations, a centric plan could stand alone, as in the octagonal church at St. Peter’s House in Capernaum. Or it could include, as well, the elements (including an apse) of the basilica plan, as we shall see. Not all the churches built around a single center were commemorative. There was, for example, a beautiful round church at Beth-Shean. Any classification or generalization must also take into account the significant number of buildings expressing individual talent, creative urge and the originality of the architect.

The majority of basilica churches were modest structures—simply congregational churches in which mass was held. They were to be found in every city, village and monastery. Others, however, were massive, monumental structures.

By 326 the Empress Helena had made her famous pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Her visit—to which many legends were later attached, such as the discovery of the True Cross and the building of a church on Mt. Sinai—played an important part in expediting the construction of the first churches. Constantine himself endowed and encouraged the construction of the first four churches in Palestine. These were all commemorative churches. They are the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, centering on Christ’s tomb; the church on the Mount of Olives (Eleona), built over a cave where, according to tradition, Jesus sat with his disciples; the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, centering on the spot where, according to tradition, Jesus was born; and the Mamre Church near Hebron, where Abraham hosted the angels (Genesis 18).b

This of course was only the beginning. Palestine is remarkable for the number of holy places connected to Biblical traditions and to the life of Jesus and his apostles, so it is particularly rich in commemorative churches (martyria, memoria).

Scholars have succeeded in reconstructing from existing remains the plans of three of the four commemorative churches built in Constantine’s lifetime. The exception is the Mamre Church, the plan of which is not clear. We will look briefly at the other three.

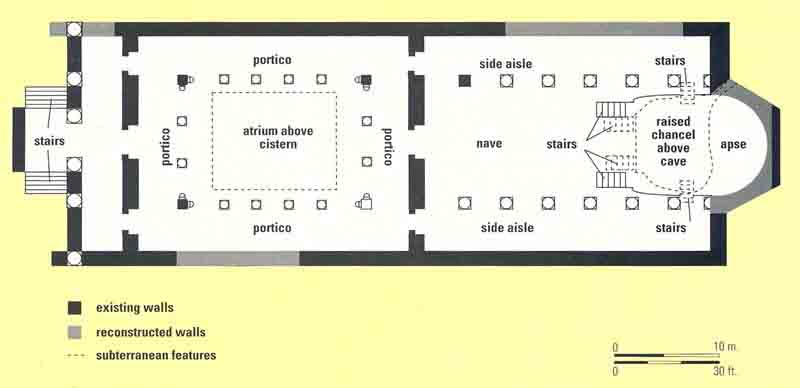

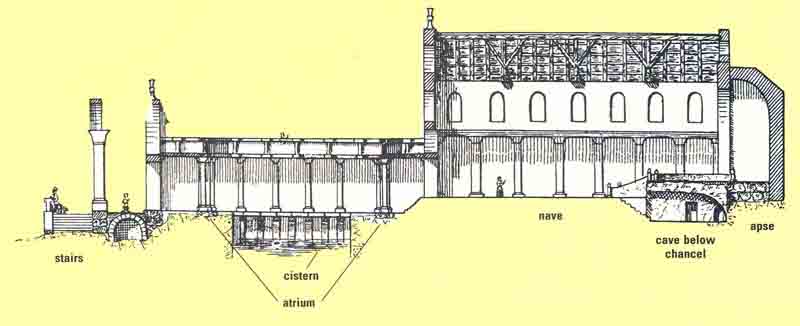

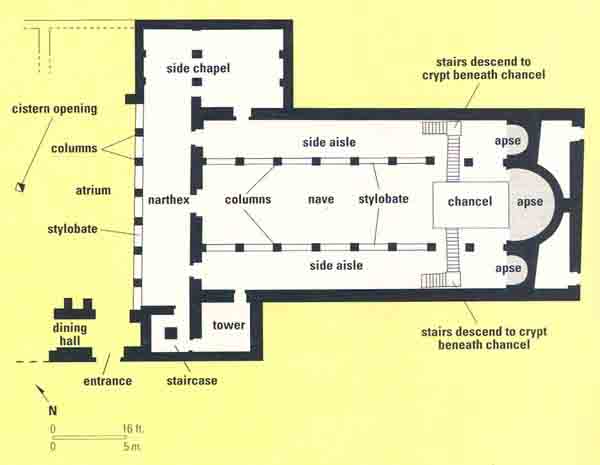

Although a memorial church, situated above a cave on the Mount of Olives facing the Temple Mount, the Eleona Church is a simple basilica. Only the foundations survived, but Louis-Hugues Vincent, the well-known French priest and Jerusalem archaeology expert from the École Biblique et Archéologique in the early days of this century, managed to reconstruct the plan of the church. True, its plan was a simple basilica, but it must have nevertheless been a magnificent structure. The nave was nearly 100 feet long. In front of the church building was a colonnaded forecourt, or atrium, another 80 feet long.

The apse of the Eleona faced east, toward the rising sun. The apse tends to be one of the most interesting parts of early church architecture. In a simple basilica, it can extend out of the back wall or it can be enclosed within the back wall. In the latter case, spaces within the building on either side of the apse would be created. In the case of the Eleona Church, the apse is on the outside.

The site of the church sits on a slope, requiring a set of steps from the outside to the forecourt and another set 037of steps up to the church itself. Inside, still another set of steps goes up to the chancel and the apse area over the cave. Actually there were two sets of steps between the nave and chancel; one to go up and other to come down. This facilitated an uninterrupted procession of worshipers and pilgrims. Masses of them must have been attracted to the cave, as they still are today.

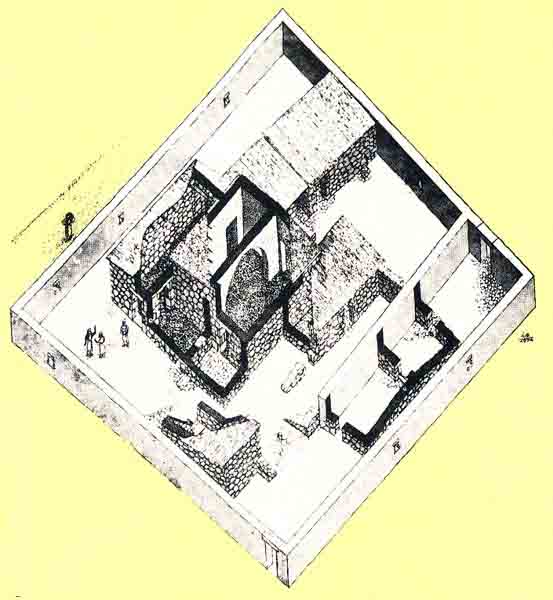

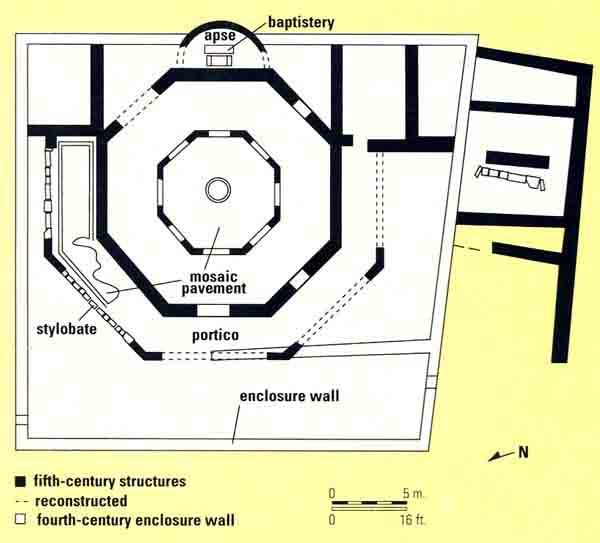

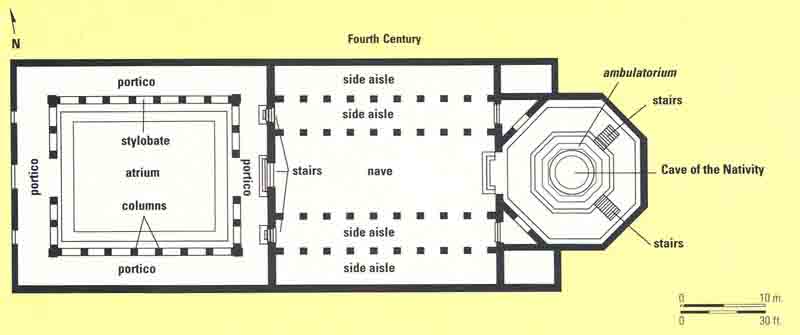

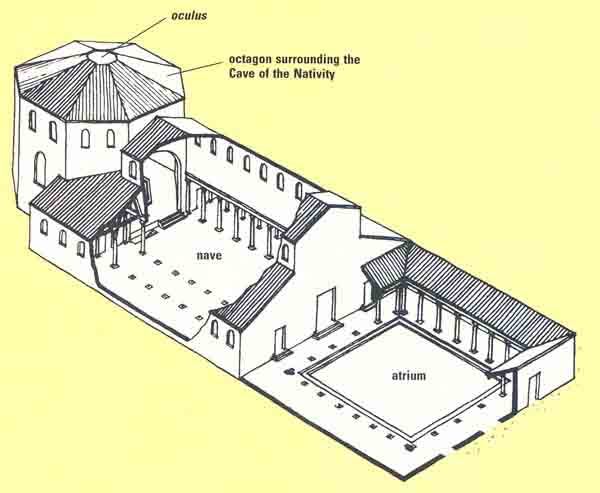

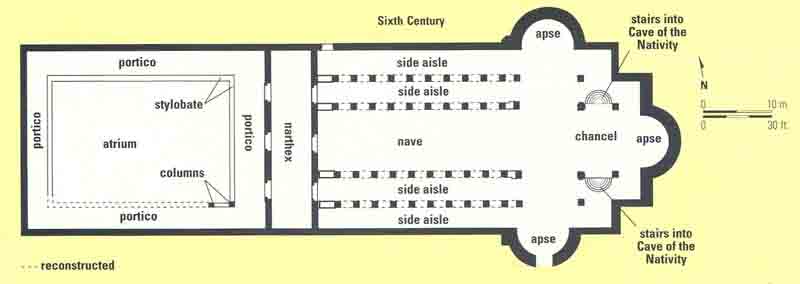

The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is also a basilica whose function is primarily commemorative. But where one would expect an apse, there is a large octagonal structure above the sacred focus of the church, the Cave of the Nativity. This Constantinian structure thus combined a centric memorial church with a basilica plan.

Each of the octagon’s eight sides is over 25 feet long. Originally, it was covered, according to the usual reconstruction, by a conical wooden roof. In the center of the floor was an opening surrounded by a balustrade that in turn was surrounded by a walkway, or ambulatorium. As they walked around the ambulatorium, the faithful could look down at the place of the nativity. An oculus (eye), an opening in the ceiling, was set in the apex of the octagonal roof in perfect alignment with the birthplace.

The main church included a hall of a typical basilica plan about 80 feet long. Two rows of columns on either side of the nave created four side aisles, in contrast to the Eleona Church, which had only one row of columns on either side and only two aisles.

The raised octagonal area in the Church of the Nativity was reached by stairs from the aisles—probably one side for ascending and the other for descending. In the atrium, in front of the church, four porticoes enclosed a square open courtyard.

The octagonal structure above the nativity cave recalls the mausoleum ordered by Emperor Diocletian for himself in Spalato in Dalmatia (today Split, former Yugoslavia). Perhaps this is a prime example of the direct influence of imperial commemorative architecture on that of the Christians.

The overall plan of the Church of the Nativity facilitates the viewing of the nativity place by large groups of pilgrims. In this respect, attaching a large basilica to an octagon with a pointed top was well suited to the particular needs of the site. But this plan also had a serious drawback in that it did not allow space for regular Christian service, for the altar and for the priests. If Communion was held in the church, which is quite likely, it must have taken place under particularly uncomfortable conditions.

In the sixth century, this drawback was corrected in a reconstruction of the building under the emperor Justinian. That is what we see in the Church of Nativity today. The nave was not greatly changed, but a narthex was added at the western end of the church (cutting off part of the atrium). The most important change, however, was made at the other end of the church. The octagon was removed and in its place three apses in a cloverleaf array were erected. At that stage the difficulties that had stood in the way of celebrating the Mass were eliminated, and it was possible to install a chancel and altar in the church and to hold regular prayer services and ceremonies. The pilgrims, who were mainly interested, as they are today, in visiting the Cave of the Nativity, and not in the daily prayers of the church, entered the cave by a flight of stairs on one side and left by another flight of stairs on the other side. Thus it was possible to maintain the daily services without interference while large numbers of pilgrims were visiting the cave below the chancel.

Some scholars have tried to date the various stages in the evolution of ecclesiastic architecture, but the effort has been largely unsuccessful. Not infrequently, we find churches built in the sixth and seventh centuries C.E. according to a simpler, and what would at first glance appear to be an earlier, design.

A chronological development did occur with respect to the apse, however. From the mid-fifth century on, a new type of basilica became common in Palestine. Instead of a room on either side of the central apse, two small apses were built, creating a “triapsidal” basilica. This was not like the cloverleaf apse in the Church of the Nativity, but consisted of a large central apse with a smaller one on either side. An excellent example is to be found in the Northern Church at Rehovot-in-the-Negev.

Another common element from the fifth century onward was the addition of a narthex, a place for the not-yet-baptized members of the congregation to assemble during the Mass. The narthex also created a kind of transition at the entrance to the church from the profane outside world to the sanctified interior.

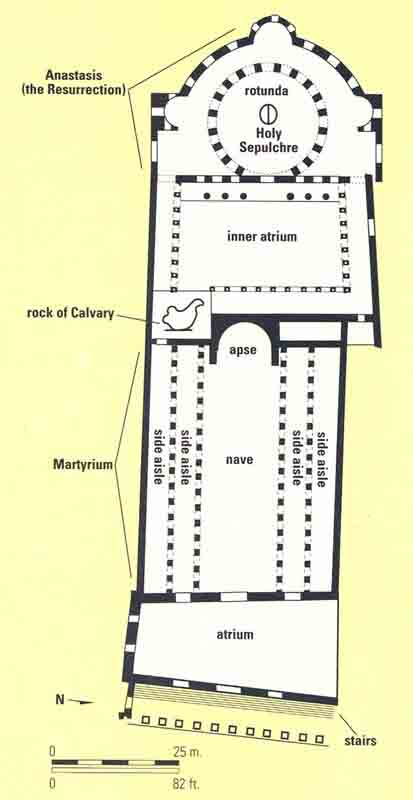

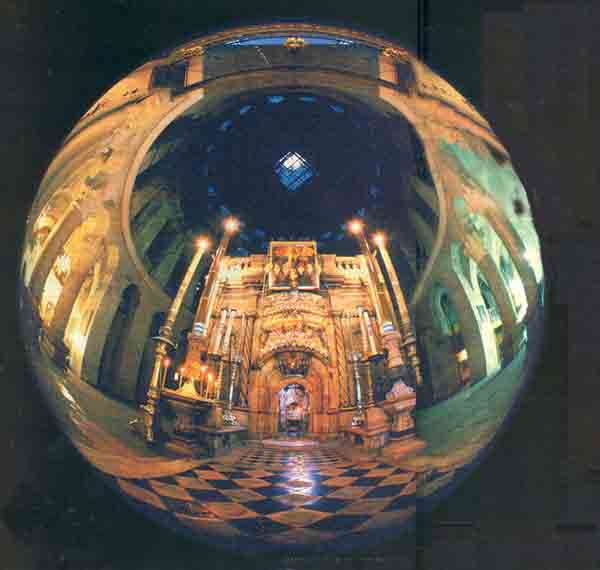

The most important church in Palestine was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. BAR readers are already familiar with the evolution and reconstruction of this magnificent structure, 039including the changes in the Crusader period that fundamentally altered the building.c The earlier compound was entered, as shown on the famous sixth-century Madaba map, from the Cardo Maximus, the main thoroughfare of the city. Steps led to an atrium, from which a basilica church was entered. According to Charles Couasnon, O.P., the French architect who studied the building in the 1960s, the civic basilica of Roman Jerusalem had been previously located here, and part of the foundations of the Roman basilica were used for the Christian building; unlike a pagan temple, the Roman civic basilica was not considered impure. Some of those foundations were unearthed in excavations in parts of the church. The apse of the Constantinian basilica was found beneath the floor of today’s Greek Catholikon.

Behind the basilica, to the west, was another courtyard, a kind of inner atrium, in front of the tomb. The Holy Sepulchre itself rose beyond the inner atrium, to the west. In the early stage, the tomb stood like a monument carved in the rock within an open courtyard. Later in the fourth century, this tomb was surrounded by a rotunda, a round colonnaded building with a wooden domed roof, which served to ornament the tomb like a gigantic canopy. The rotunda was about 115 feet in diameter. Parts of the original wall of the rotunda stand to this day, rising to a height of about 35 feet, and serve as the foundation for the walls of the present rotunda around the tomb. This part of the church compound was called the Anastasis (meaning “the resurrection”). The difference between the rotunda, with its single focus, built for commemorative purposes over the holy tomb, and the basilica, which was used for worship, is clear both in the plan of the building and in its use.

Most of the Byzantine churches discovered in Israel are small, modest structures compared to the Constantinian churches. The former served rural or urban congregations or monasteries. Even the smallest villages had a church, and middle-sized towns had a number of them.

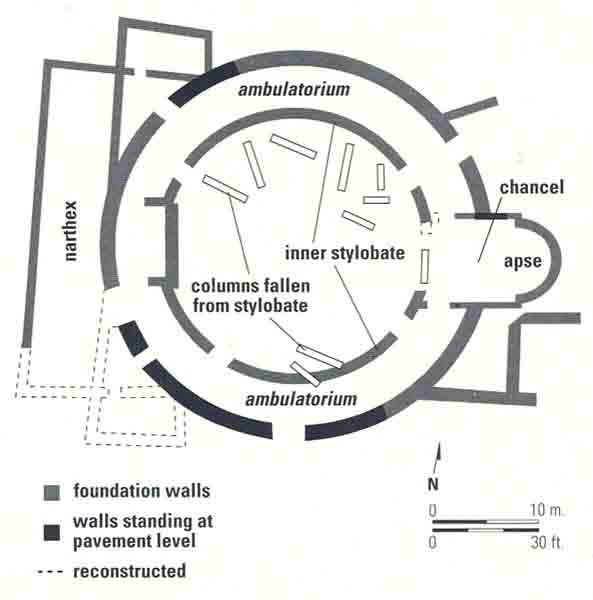

Among the many centric-plan memorial churches in Palestine was a circular one on the summit of the Mount of Olives known as the Church of the Ascension, enclosing the rock from which Jesus is supposed to have ascended to heaven.

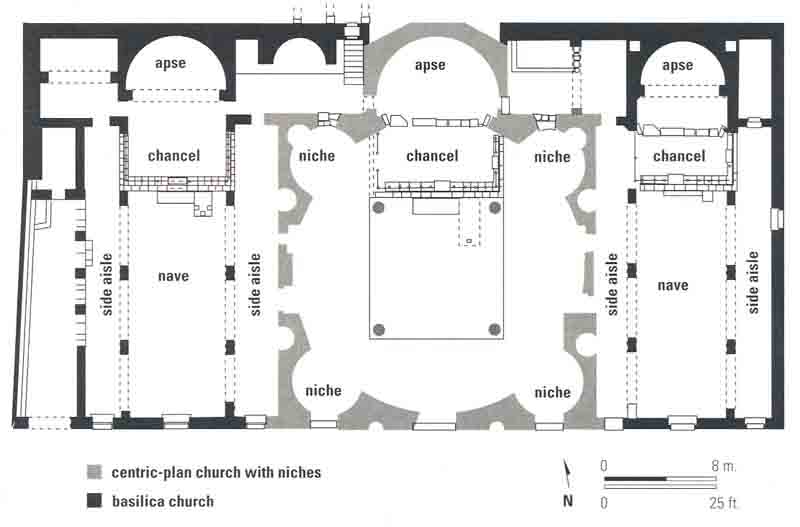

In addition, a number of nonmemorial churches took unusual shapes. The circular church at Beth-Shean has already been mentioned. We can end this brief survey with the church complex of John the Baptist, a sixth-century structure at Gerasa. There an interior circular structure with niches is flanked on either side by basilica chapels.

After the Arab conquest in the seventh century, few significant church structures were built until the Crusaders’ building initiative in the 12th century, which brought in its wake another flowering of church construction, but far different from the Byzantine churches. That, however, must be the subject of another article.

(This article has been adapted from the first chapter of Ancient Churches Revealed, ed. Yoram Tsafrir [Israel Exploration Society and Biblical Archaeology Society, 1993].)

More ancient churches have been found in the Holy Land than in any area of comparable size in the world. About 330 different sites with ancient church remains have been identified in modern Israel, the West Bank and the Golan Heights east of the Sea of Galilee. At many of these sites, more than one ancient church stood. At Madaba in Transjordan (not included in our survey area), 14 turned up. In Jerusalem there were several dozen churches and chapels. In all, about 390 ancient churches at these 330 sites have been discovered. Almost none, however, are earlier than […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See James F. Strange and Hershel Shanks, “Has the House Where Jesus Stayed in Capernaum Been Found?” BAR 08:06.

Here the angels announced to Abraham and Sarah the birth of their son Isaac, in Christian tradition this was a prefiguration of the annunciation to Mary by the angels (Luke 1:26–38).

See Dan Bahat, “Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial Place of Jesus?” BAR 12:03.