“You know that the Olympic crown is olive, yet many have honored it above life,” wrote the Greek orator Dio Chrysostom (c. 40-110 C.E.).1 Indeed, the occasional philosopher or doctor may have condemned the brutality and danger of ancient athletics, but the Greek public nevertheless accepted a good deal of hazard, injury and death.2

This is particularly true of the three Greek combat events—wrestling, boxing and pancratium (a combination of boxing and wrestling that allowed such tactics as kicking and strangling). Their history at ancient Olympia is long and eventful: Wrestling entered the program in 708 B.C.E., boxing in 688 B.C.E. and pancratium in 648 B.C.E. These grueling sports reveal much about the aspirations and values of ancient Greece, about what was deemed honorable, fair and beautiful, both in the eyes of those of who competed and those who traveled to Olympia to watch.

Combat sports were designed to be as physically taxing and uncomfortable as possible. This meant no time limits, no rounds, no rest periods, no respite from the midsummer sun. According to some ancient authors, such as Cicero (106-43 B.C.E.) and Philostratus (third century C.E.), boxers could bear their opponents’ blows more readily than the unremitting heat.3 And the combat athlete might well have gone from one hard-earned and injurious victory straight into another round of competition.

Nor were there weight classes, so the ambitious but undersized athlete simply took his chances against larger competitors. In the event of a mismatch, the superior athlete was unlikely to show mercy. Some athletes were so terrifying that their opponents simply defaulted, allowing them to win akoniti (dust-free), without having to get dirty. A late-second-century C.E. athlete named Marcus Aurelius Asclepiades—who won the pancratium at many festivals, including the games held at Olympia—boasted in an inscription that he “stopped all (potential) opponents after the first round.”4 An inscription honoring the wrestler Tiberius Claudius Marcianus recounts that at one festival, “when he undressed, all his opponents begged to be dismissed from the contest.”5

The ancient Olympic world adhered to values very different from our own (or what we ideally think of as our own). In a speech given in 1908, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, said: “The purpose of these Olympiads is less to win than to take part in them,”6 a sentiment later echoed by the sportswriter Grantland Rice:

For when the One Great Scorer comes

to mark against your name,

He writes—not that you won or lost—

but how you played the Game.

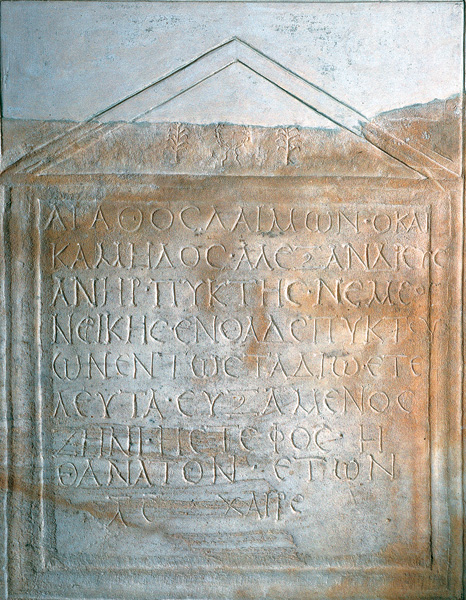

The ancient Greeks did not view their Olympics in this way. A second-century C.E. inscription found at Olympia relates the ancient Olympic spirit with quiet dignity:

Agathos Daimon, nicknamed “the Camel” from Alexandria, a victor at Nemea. He died here, boxing in the stadium, having prayed to Zeus for victory or death. Age 35. Farewell.7

The chasm between ancient and modern widens further once we look more closely at the specific combat events contested at the panhellenic games.

The Association Internationale de Boxe Amateur, whose rules govern modern Olympic boxing, has precise requirements for boxing gloves—they must weigh 10 ounces, half of that weight consisting of padding, and they must be engineered to absorb, rather than transmit, shock. Association boxers must also wear headgear, mouth guards and ear protectors during their bouts; they must also use protection for the groin and lower abdomen. According to the guidelines of the Atlantic branch of the U.S. Amateur Boxing Association, “The main objective of Olympic-style boxing’s rules and the actions and decisions of the referee is the safety and protection of boxers.” What is remarkable about ancient Olympic boxing is that the Greeks recognized a number of ways to make the sport safer—and ignored all of them.

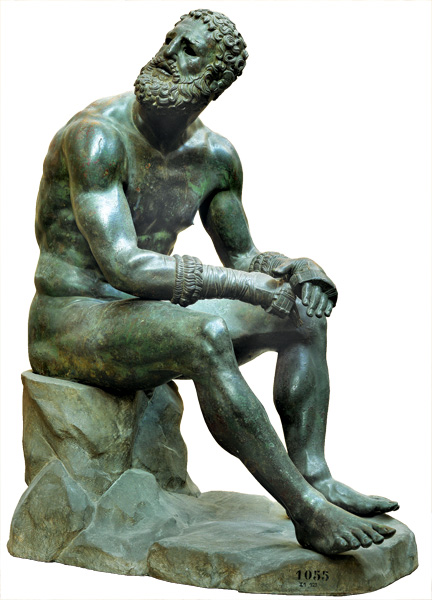

“A boxer’s victory is gained in blood,” begins an inscription dating from the first century B.C.E., praising a tough and successful boxer.8 The Greeks celebrated the hazards of boxing and the damage it caused, and their art did nothing to sanitize this damage. Boxers in vase paintings bleed from the nose; sculpted statues show broken noses and cauliflower ears. A second-century C.E. manual on the interpretation of dreams, by the Greek soothsayer Artemidorus, observes that boxing dreams ominously foretell a deformed face and loss of blood.9

Until the fourth century B.C.E., Greek boxers bound their hands with thin strips of oxhide. These “soft thongs” (himantes meilichai), as the Greeks called them, did nothing to protect boxers against concussions or facial lacerations. On the contrary, they protected the boxer’s knuckles against fracture and the wrist against sprain: In effect, they simply encouraged more vigorous and damaging blows. The “sharp thongs” (himas oxus) that replaced them—consisting of a pad of leather, 1 to 2 inches thick, tied over the boxer’s knuckles—were even more damaging. Exactly when they became standard equipment is unclear, but a vase dated 336 B.C.E. shows a highly developed form of the thongs.

In Book 8 of the Laws, Plato says that during practice sessions boxers put on padded gloves called sphairai instead of thongs.10 These padded gloves, however, were never used in competition. Needless to say, modern attempts to protect a boxer’s eyes from injury—by mandating gloves that keep the thumb from being bound together with the fist—find no parallel in antiquity; ancient texts mention boxers whose eyes had been struck out.11

The boxing rules enforced by the judges at Olympia were minimal. As in other sports, boys and men competed in separate events—though, as already noted, there were no weight divisions that protected the welterweight from the crushing blows of the heavyweight. Clinching (the act of holding onto your opponent’s body to slow a fight down) was forbidden, and we find depictions of judges using their sticks to punish such infractions. Technique mattered insofar as it led to submission or insensibility; the concept of winning by points or by judges’ decision is modern, not ancient. In the absence of a knockout (or worse), the vanquished pugilist could hold up a finger to signal submission, a moment often seen in Greek vase paintings.

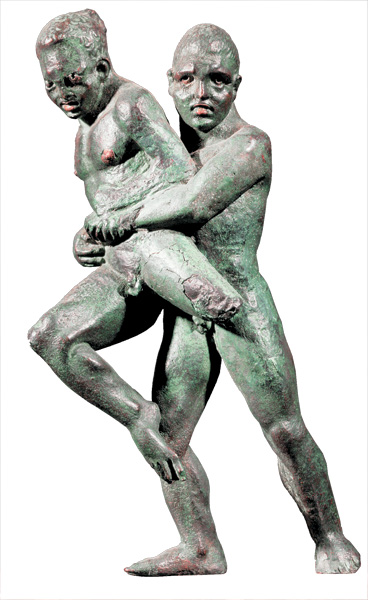

Unlike boxing and pancratium, a wrestling match typically did not end with submission or incapacitation, but rather with one competitor achieving technical mastery over his opponent. The ancients admired wrestling for the level of skill and science it required. Homer’s Odysseus is the archetypal clever wrestler who deflects and neutralizes the massive strength of a far larger man (Ajax) in Book 23 of the Iliad. A statue honoring one Aristodamus of Elis for his victory at Olympia in 388 B.C.E. is inscribed with text reading, “I did not win by virtue of the size of my body, but by my technique.”12 In the Laws, Plato praised wrestling as a form of exercise well suited for the training of Athens’s youth. Plutarch referred to the sport as “the most technical and the trickiest,” and a surviving section of a first- or second-century C.E. wrestling manual shows how well developed the drills for tactics and counter tactics were.13

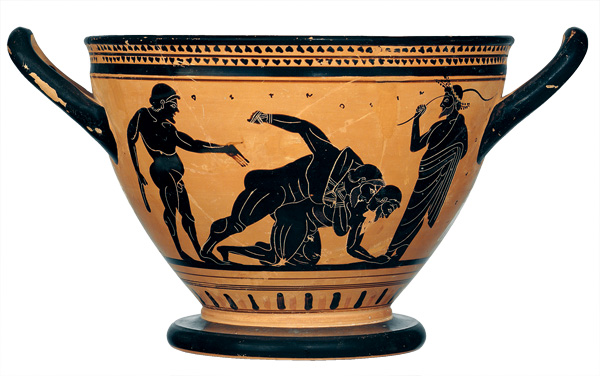

To gain a fall, the Greek wrestler had to take his opponent down, making the man’s back or shoulders touch the ground or stretching him out prone. Three falls were necessary to win a contest. Not every fall was clear. Greek literature sometimes refers to disputes over whether a fall occurred.14 The tactics depicted in Greek art suggest that very forceful holds and throws were common. Vase paintings and sculpture show headlocks and hip throws, shoulder throws and body lifts, including the reverse body lift that the formidable Russian wrestler Aleksander Karelin has used with such devastating effect in recent Olympiads. If a fall did not result from a wrestler’s being thrown on his back, action would continue on the ground. Joints could be forced against their normal range of movement, and sculptures show a variety of arm bars and shoulder locks that would be illegal in modern Olympic wrestling.

The struggle was likely to be bitter and intense, however sophisticated the tactics. Greek sources are quite clear that choking an opponent into submission, though apparently uncommon, could result in a legitimate fall.15 The great British historian of ancient sport E.N. Gardiner (1864-1930) may have written that “Wrestling, at all events in the early days before it was corrupted by professionalism, was free from all suggestions of that brutality which has often brought discredit on one of the noblest of sports,”16 but the evidence proves otherwise. A recently discovered inscription from Olympia records a judges’ decree passed in the late sixth century B.C.E. forbidding wrestlers to break each other’s fingers and empowering the judges to flog athletes who disobeyed the rule.17 Nevertheless, Leontiskos of Messene won the Olympic crown in wrestling in both 456 and 452 B.C.E. by using this tactic.18

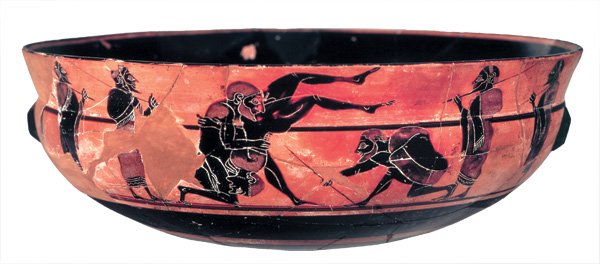

Aside from biting or gouging into the soft parts of an opponent, all means of unarmed combat were legal in pancratium. A Greek synonym for pancratium, pammachon (total fight), describes the sport well. In fact, pancratium differed from modern “extreme fighting” largely by virtue of its having been a central, rather than marginal, part of the athletic world of its day. Exhibiting the power and extension of the legs, kicking was an essential part of pancratium, almost to the point of being an emblem of the sport. Driving the knee into an opponent’s genitals was a particularly effective tactic. Pancratiasts also punched and applied strangle holds and locks on their opponents’ limbs and joints, all with the purpose of forcing their rivals to concede the contest. One famous pancratiast, Sostratos of Sikyon, won 12 crowns at Nemea and Corinth, two at Delphi and three at Olympia (in 364, 360 and 356 B.C.E.) by using Leontiskos of Messene’s trick of bending back an opponent’s fingers. Sostratos used the tactic so effectively that many potential opponents forfeited their matches rather than meet him in the stadium.19

In his Anacharsis, the second-century B.C.E. writer Lucian imagined a typical pancratium bout:

These folk standing up, who also have been coated with dust, punch and kick at each other in their attacks. And now this poor wretch looks like he is going to spit out even his teeth—his mouth is so full of blood and sand, having just taken a blow on the jaw.20

Typically, pancratiasts fought bare-fisted, leaving the hands free for wrestling and strangling holds, but at least two vase paintings show that sometimes they preferred the lacerative potential of the thong.

Gouging and biting were punished as foul play, and one vase painting shows a trainer vigorously flogging two pancratiasts for digging into each other’s faces. Greek authors, including the physician Galen (c. 129-199 C.E.), observed that quite a lot of gouging and biting did take place nonetheless—which is not entirely surprising in a contest that permitted, and rewarded, snapping an opponent’s fingers and kicking his genitals.

It is hard to say how often contests turned lethal. Greek texts seem quite clear that boxing was regarded as more injurious and dangerous than pancratium. But pancratium’s hazards were very real, as is best evidenced by the extraordinary story of one Arrhichion.

Arrhichion of Phigalia had twice won the pancratium event at Olympia. In 564 B.C.E., his third attempt to win an Olympic crown, he advanced to the finals. During the final bout, Arrhichion was standing up when his opponent, whose name is not recorded, jumped on his back, clamped a leg scissors around his waist and strangled him with a forearm against his throat. Realizing that he was suffocating, Arrhichion chose to exit Olympia in a blaze of glory. Catching his opponent’s right ankle in the crook of his right knee, he clamped his opponent’s left leg to his own body with his left arm, thus preventing his opponent from releasing the hold. As he lost consciousness, Arrhichion fell toward the left while straightening his right leg against his opponent’s ankle, wrenching it from its socket. His opponent, in agony, threw his hand in the air, signaling concession, not realizing, as he fell, that Arrhichion’s corpse lay beneath him.

Just who participated in these grueling and often injurious ancient contests? The evidence is clear: everyone from blue bloods to men of modest means.21 Diagoras of Rhodes, who boasted of both royal and mythical lineage (he claimed to be descended from Herakles), won in boxing at the 464 B.C.E. Olympics. His three sons all won Olympic events in boxing or pancratium, and his two grandsons won Olympic crowns in boxing.22 In the first or second century C.E., Tiberius Claudius Rufus of Smyrna battled an opponent in the finals of the pancratium at Olympia until darkness and the bravery of the performers convinced the judges to award both men the Olympic crown; the inscription honoring Tiberius Claudius Rufus notes that he was a personal acquaintance of the Roman emperor, implying the significant wealth and prestige of his family.23

Aristotle, on the other hand, tells of a fishmonger who won the boxing crown at Olympia (unfortunately, he provides no further details),24 and the snobbish fifth-century B.C.E. Athenian general Alcibiades competed only in chariot racing, explaining that the other contests were populated by men of humble birth.25 Indeed, one manifestation of the Greeks’ democratic brilliance is that at ancient Olympia, competitors—rich or poor, aristocrats or tradesmen—were simply athletes; stripped naked for competition, they sought to prove they were the best in the Greek world. Although the incentive of valuable prizes or money (which the victors received at all ancient games, including those at Olympia) might have been powerful, especially for those of slender means, it does not explain why wealthy aristocrats eagerly joined in contests of this nature.

The lure for all Greeks was kleos (fame), the perfect antidote to the grim, disembodied obscurity of death. The Homeric poems, which were for the Greeks what the Bible became for later Western society, are permeated with the deeds of heroes, for which they are rewarded with kleos. Hector, the eldest son of King Priam and the Trojans’ greatest warrior, speaks for all when he says that his heart did not know how to shrink back in battle, since the time “when [he] learned to be brave and always to fight in the front ranks of the Trojans, guarding [his] father’s honor and [his] own also” (Iliad 22.458-59).

In time, however, phalanx warfare, with its highly organized ranks and files, eliminated the need for one-on-one combat, which figured centrally in the battles of an earlier age (as, perhaps, preserved in Homer). Greek city-states thus came to view their wartime victories as the achievements of the entire people, not of a heroic general, however brilliant or valorous he might have been.26

Only in combat sports could the Greek man prove his mettle in fighting one-on-one. (Indeed, nowhere else in Greek civic life was aggression both tolerated and encouraged. We know from surviving court speeches that the Athenians severely punished even casual acts of assault and battery with sanctions including the death penalty.)27 By placing combat sports in the context of warfare, we can understand the baffling paradoxes of what the Greeks considered fair play. Just as on the battlefield, no handicap was awarded to smaller or weaker opponents. There were no weight classes in the combat sports to prevent a stronger man from brutalizing a weaker or less-experienced fighter. Athletes in the combat sports could not avoid thirst, discomfort or the heat of the sun, and warfare allowed for no periods of rest. The great athletic festivals, then, were a surrogate for the world of heroic combat that had vanished from Greek reality but was alive in the Homeric poems.

To win in competition was to strive for the heroic, to enjoy unending kleos. As the Greek poet Pindar (c. 522-440 B.C.E.) wrote, “He who braves the contest’s struggle with success wins the fairest sense of inner peace for the remainder of his days.”28 The modern world will rightly depart—and depart sharply—from the ancient world’s disregard for the safety of its competitors. Nevertheless, look this summer on the faces of those in Athens who brave a contest’s struggle and then prevail: Their hard-earned joy is one of the continuities between ancient and modern times.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

See Michael B. Poliakoff, Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), pp. 89-91.

See Inscriptiones Graecae 14.1102; Luigi Moretti, Iscrizioni agonistiche greche. Studi pubblicati dall’ Istituto Italiano per la Storia Antica 12 (Rome: Angelo Signorelli, 1953), no. 79; and Poliakoff, Combat Sports, p. 106.

G. Kaibel, Epigrammata Graeca (Berlin, 1878), p. 942; and Moretti, Inscrizioni agonistiche greche, no. 55.

Plato similarly recommended that soldiers engage in military exercises with weapons equipped with protective buttons on their tips. See Plato, Laws 830a-831a; see also Plutarch, Praecepta rei publicae gerendae 32 (Moralia 825e), with further discussion in Poliakoff, Combat Sports, p. 73.

Denys Page, Epigrammata Graeca, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975, LII, 283 ff; also see Joachim Ebert, Griechische Epigramme auf Sieger an gymnischen und hippischen Agonen. Abhandlungen der Saechsichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig, philologisch-historische Klasse 63.2 (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1972), no. 34.

Plato, Laws, 796b; Plutarch, Quaestiones conviviales 2.4 (Moralia 638d). For a translation of the wrestling manual, see Poliakoff, Combat Sports, pp. 52-53.

For further information on disputes over scoring a fall, see Ambrose, Commentary on Psalm 36.51, in Patrologia Latina 14.1038-39; see also Aristophanes, Knights, pp. 571-73.

Peter Siewert, “The Olympic Rules,” in Proceedings of an International Symposium on the Olympic Games, William Clulson and Helmut Kyrieleis, eds. (Athens, 1992), pp. 111-17.

Sostratos the pankratiast is known from Pausanias 6.4.1-2 and a surviving inscription: Moretti Iscrizioni agonistiche greche, no. 25; see also Ebert, Griechische Epigramme, no. 39.

See H.W. Pleket, “Games, Prizes, and Ideology,” Stadion 1 (1976), pp. 49-89; and David C. Young, The Olympic Myth of Amateur Greek Athletics (Chicago: Ares, 1984).

The story of Diagoras and his family was often told in antiquity. See in particular Pausanias 6.7.1-7 and 4.24.1-3; Pindar praised Diagoras in a victory ode, Olympian 7, and Cicero tells the story, in Tusculan Disputations 1.46.111, of a spectator who saw Diagoras carried on the shoulders of his sons who had triumphed in boxing and pancratium on the same day at Olympia; the spectator remarked, “Die, Diagoras, for you cannot go up into heaven”—in other words, there is nothing greater that any mortal man could ever have.

Tiberius Claudius Rufus’s victory is commemorated on a surviving inscription, Inscriften von Olympia 54/55. For further discussion, see Reinhold Merkelbach, Zeitschrift fur Papyrologie und Epigraphik 15 (1974), pp. 99-104; and Walter Ameling, Epigraphica Anatolica 6 (1985), p. 30.

Note how the Athenians forbade the successful generals of the Persian wars to erect monuments to themselves; see Aeschines, Against Ktesiphon, pp. 183-186, with discussion in M. Detienne, “La Phalange,” in J.-P. Vernant, ed., Problemes de la guerre en Grece ancienne (Paris, 1968), pp. 127-28; also see Poliakoff, Combat Sports, 112 ff.