Ancient WMDs

Torches & Poisons & Bees—Weapons of Mass Destruction in the Ancient World

026

027

Most people assume that biological and chemical weapons are recent inventions, that only our advanced knowledge of science and weapons systems has allowed us to make use of toxins, pathogens and incendiary chemicals. Many historians have assumed, moreover, that the rules of engagement in ancient warfare—predicated on honor, valor and skill—would have banned the use of poisons and other underhanded weapons. In fact, ancient warrior cultures used such weapons more extensively than has been realized, and their attitudes toward unconventional warfare were complex and ambivalent.

In antiquity, nature was weaponized in an amazing number of ways. One could create toxic projectiles, con-taminate wells, poison food supplies, drive infected animals into enemy territory, maneuver armies into camping in malar-ial marshes, create noxious clouds of smoke to choke and blind one’s foe, drug adversaries into unconsciousness, spread plague by sticking victims with needles or boobytrapping temple treasures with contagion, catapult red-hot sand and heated metal shrapnel, fill a ship with combustible fuel and let the wind drive it toward the enemy fleet, hurl hives filled with furious hornets, train elephants to serve as living tanks, use squealing pigs 028set afire to repel an enemy’s war elephants, set rank-smelling camels against cavalry horses, pour burning petroleum on attackers, or toss naphtha grenades. All these tactics, and more, are reported in the ancient literature of Greece, Rome and India.

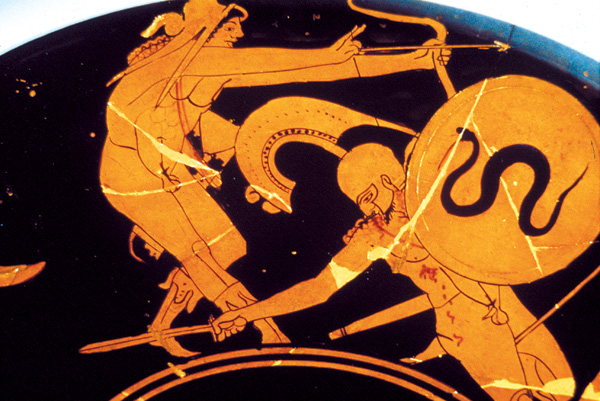

The Scythians, nomads from the Eurasian steppes, were dreaded for their use of poisoned arrows. In the Tristia, the Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C.-17 A.D.) wrote that “to make wounds twice as deadly, these men dip in viper’s venom every arrow-tip.” The Scythians also took the putrefied carcasses of venomous vipers and mixed them with human blood and dung, then left the mixture to rot over several months. A mere nick from an arrow dipped in this lethal concoction (called scythicon) could result in death or an ever-festering wound. Because the Scythians’ poison was well known, they possessed an immense psychological advantage over an enemy, and their scythicon surely deterred more than a few attacks.

The ancient Indians also created poisons from deadly snakes. According to the Roman historian Aelian (170–235 A.D.), one of the most feared toxins derived from the so-called “Purple Snake from the hottest part of India.” This snake—which may have been the rare viper Azemiops feae, the only tropical Asian snake that fits Aelian’s description of a short, dark, purplish reptile with a pure white head—was suspended upside down over a pot that collected dripping venom. The venom 029congealed into a thick amber gum. When the snake died, another pot was used to collect the watery serum flowing from the rotting body; this liquid jelled into a thick black substance. The amber venom caused violent convulsions. Aelian reports that the “victim’s brain dissolved and dripped out his nose and he died a horrible death.” The black sludge caused a slow death from tissue destruction and puss-oozing wounds.

Another South Asian snake, the deadly Russell’s viper, was probably responsible for the severity of the casualties suffered by Alexander the Great’s army when he attacked the city of Harmatelia (in modern Pakistan) in about 326 B.C. Many of those who were only slightly wounded in battle suffered numbness, stabbing pain, convulsions and gangrene—culminating in a horrible death. The Hindu doctors accompanying Alexander recognized the symptoms and realized that the Harmatelians had coated their arrows and swords with snake venom.

Snakes also figured in a second-century B.C. naval battle between Eumenes of Pergamum (on the Aegean coast of Anatolia) and the great Carthaginian commander Hannibal. According to the Roman historian Cornelius Nepos (110–24 B.C.) and the military strategist Frontinus (who died in 103 030A.D.), Hannibal found his troops outnumbered, so he sent his sailors ashore to capture great quantities of venomous snakes. The sailors stuffed the serpents into earthenware jars, then catapulted the vessels onto Eumenes’s ships. When the pottery began smashing around them, Eumenes’s men laughed derisively. But as soon as they realized that their decks were seething with snakes, they frantically tried to avoid the reptiles. Eumenes’s navy was overcome, and it may have been this incident that led him to make the famous statement that no honorable commander should seek victory by using methods he would not want turned against himself.

The Romans encountered several cultures that used plant poisons and snake venoms on their projectiles. The poet-politician Silius Italicus (c. 26–102 A.D.) reported in the Punica that the Nubians of upper Egypt and Sudan dipped their javelins in noxious plant juices, and that the Nasamonians of north Africa “were skilled at disarming serpents of their fell poison.” The geographer Strabo (c. 60 B.C.-21 A.D.), in his Geography, described an Ethiopian tribe that smeared snake venom on its spears. Strabo also claimed that the arrows of the Soanes, who inhabited the Caucasus, delivered a poison so virulent that just the reek of a shower of missiles could fell a warrior.a

And then there was yew, the tall, dark, dense and highly toxic evergreen tree, often seen in cemeteries, that has symbolized death since antiquity. According to the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23–79 A.D.), to nap or picnic under a yew tree could spell doom. Yews contain a strong 031alkaloid poison, which causes sudden death by suppressing the heartbeat. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder writes that in Spain, which the Romans conquered in the second century B.C., souvenir flasks were carved from yew wood and sold to Roman tourists, many of whom died after drinking from them. Could this have been a sly form of biological sabotage?

The Romans themselves resorted to using poisons in order to destroy their enemies. The Roman general Aquillius, for example, fought a drawn-out and expensive war in the second century B.C. to quell revolts by several cities in Asia Minor; these cities were led by Aristonicus of Pergamum. In 131 B.C. Aquillius finally achieved victory by poisoning the rebelling cities’ water supplies.b The second-century A.D. Roman historian Florus railed against Aquillus for shamefully utilizing poison, which violated the Roman ideal of honorable war (Florus’s treatise on Roman history and war is titled the Abridgement of All the Wars Over 700 Years).

Of course, Florus conveniently forgot that in Rome’s own foundation epic, Virgil’s Aeneid (which tells of the founding of Rome by the Trojan prince Aeneas), one of the founding fathers, Amycus, is described as an expert in “steeping metal with poison.”

048

Even Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) turned to poison. In about 75 B.C., he was kidnapped by Cilician pirates who were infesting the Aegean (the Cilicians were based on the coast of modern Syria). To escape, according to the military historian Polyaenus, Caesar poisoned his captors’ wine with mandrake.

Despite this experience with underhanded warfare, the Romans were totally unprepared for the chemical weapons used by the fortified cities between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. For the Romans, petroleum was a mysterious, rare substance, used for religious rituals and magic tricks. But since about 900 B.C., the people of ancient Mesopotamia had found myriad uses—including military ones—for the sticky, extremely flammable oil and volatile naphtha that seeped from the sand.

The devastating new chemical weapons were deployed against an imperial army led by Licinius Lucullus from 74 to 66 B.C. According to Pliny, the defenders of Samosata, a fortified city on the Euphrates, gathered a “flammable mud that exudes from nearby pools. Once it is ignited, it is impossible to quench 050with water.” From the city walls, Pliny wrote, the Samosatans poured the burning mud on the Romans and their siege engines. The historian Dio Cassius (c. 164–229 A.D.) reported that at Hatra, a desert stronghold between the Tigris and Euphrates, a remarkable burning substance enveloped the Roman army in searing flames. According to Dio Cassius, the Mesopotamian “barbarians have an extraordinary chemical that burns up whatever it touches and cannot be extinguished with any liquid.”

Lucullus had a hard time of it. During his campaigns in the Black Sea region, he had to contend with the hornets and wild bears that were released into his siege tunnels. And in Armenia his forces came under relentless fire from the local nomads, who not only steeped their arrows in snake venom but also designed diabolical arrowheads with hinged points that broke off in a victim’s flesh when the arrows were pulled out.

Lucullus was recalled to Rome in 67 B.C., and Pompey (106–48 B.C.) assumed command. In about 65 B.C. Pompey’s troops fell victim to yet another innovative biological weapon during their campaign in the Black Sea region. According to Strabo, the Heptakometes of Colchis placed wild honeycombs dripping with toxic honey (made from poisonous rhododendron nectar) along the route of the advancing Romans. The soldiers stopped to enjoy the treat, only to succumb to the honey’s neurotoxins; reeling and babbling, they collapsed, unable to move or defend themselves. In this way, the Heptakometes easily wiped out about 1,000 of Pompey’s men.

In 198–199 A.D. the Romans tried yet again to subdue Mesopotamia, with the emperor Septimius Severus twice attempting to storm Hatra. The first time, Hatra’s defenders poured naphtha on the Roman soldiers and their siege engines; the second time, they lobbed scorpion bombs—terracotta pots filled with scorpions and other stinging insects—at the invaders. The powerful Romans, the siege masters of the ancient world, failed to breach Hatra’s walls.c The fortress remained independent until 241 A.D., when the Sasanids of Iran reduced it to ruins.

Weapons using lethal poisons, volatile chemicals, windborne smoke, unquenchable flames, virulent pathogens, toxic creatures and unpredictable animals posed dangers not just to the victims but to the perpetrators themselves. Biological and chemical weapons have always been difficult to control, and the potential for blowback and friendly fire is considerable. Besides the practical problems, such tactics could also bring moral censure; in warrior cultures that valued bravery and military prowess, using secret biological weapons was often viewed as cowardly ambush.

Given these tensions about what was acceptable and unacceptable in war, what kinds of situations justified the use of biological and chemical weapons? Self-defense was a common rationale in antiquity, and that excuse is still used to justify biological and chemical armaments. Besieged cities could turn to bio-weapons as a last resort against powerful invaders. Biological measures could also be justified against adversaries regarded as “uncivilized” barbarians. Quelling rebellions and waging holy wars also encouraged the indiscriminate use of such weapons against entire populations. When one’s forces were outnumbered, when trying to break a stalemate or siege, or when fighting troops superior in courage, skill, bravery or technology, biological strategies were a real advantage. Of course, there were ruthless commanders who had no qualms about using any strategy or weapon at hand to win victory, regardless of motive or circumstance.

The evidence from antiquity shatters the notion of a time innocent of underhanded warfare. Perhaps we can take some solace in the fact that doubts about the propriety of biological and chemical weapons arose as soon as the first archer dipped his 051arrow in poison.

Myth, too, offers a glimmer of hope. The first biological weapons known from the pages of Western literature are the arrows that Hercules dipped in the venomous blood of the hundred-headed Hydra. The Greek archer Philoctetes inherited Hercules’s quiver of poisoned arrows and took the weapons with him to the Trojan War. But he accidentally dropped one of the arrows on his foot, resulting in a grievous, festering wound. Only after ten years of torture and pain did he finally arrive in Troy, where, upon being cured by the Greek doctor Machaon, he began cutting down Trojans with his poisoned arrows.

After the war, however, Philoctetes did not pass his weapons on, as Hercules had done to him. He knew their dire effects all too well. So, he dedicated his bow and arrows to a temple of Apollo, the god of healing—a fitting and symbolic end.

Most people assume that biological and chemical weapons are recent inventions, that only our advanced knowledge of science and weapons systems has allowed us to make use of toxins, pathogens and incendiary chemicals. Many historians have assumed, moreover, that the rules of engagement in ancient warfare—predicated on honor, valor and skill—would have banned the use of poisons and other underhanded weapons. In fact, ancient warrior cultures used such weapons more extensively than has been realized, and their attitudes toward unconventional warfare were complex and ambivalent. In antiquity, nature was weaponized in an amazing number of ways. One could […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Other popular arrow poisons included aconite, or monkshood, a widespread toxic plant that paralyzes the nervous system, and hemlock (the poison that Socrates was condemned to drink), supposedly favored by archers around the Black Sea.

The Romans were not the first to poison an enemy’s water supply, and they certainly weren’t the last. The earliest recorded instance occurred in 590 B.C., during the First Sacred War in Greece, when an alliance of city-states waged a holy war against the city of Kirrha (near Delphi) for offenses against the god Apollo. The alliance laid siege to the city, then poured poisonous hellebore (Christmas rose) into the stream that supplied the Kirrhans’ drinking water. After the war, the Greek alliance regretted the ignoble strategy and vowed among themselves never again to interfere with one another’s water sources. The rule would be broken countless times.

For more on ancient siege warfare, see Paul Bentley Kern, “Under Siege! How the Ancients Waged War,” Archaeology Odyssey, January/February 2004.