Archaeology for the Young of All Ages

An archaeology series for kids teaches adults as well

002

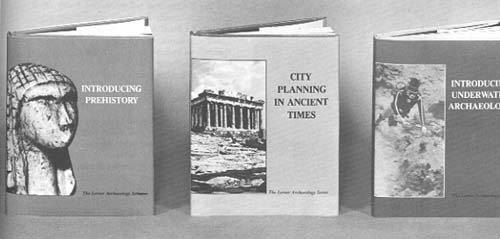

The Lerner Archaeological Series is written for readers twelve and above, but like many well written books for youngsters, this series can be enjoyable and informative to adults as well.

Individual volumes are about 85 pages long and cover a single subject area, like coins, scrolls, jewelry, mosaics, pottery, pre-history, underwater archaeology, and weapons and warfare of ancient times. An introductory volume entitled Search for the Past by the late Professor Michael Avi-Yonah, takes the young reader to a typical archaeological expedition, explaining how the site was selected, how the expedition was organized and how the site is excavated. Avi-Yonah describes the grid system of digging, the careful record keeping, the registration of finds by physical location in the stratum where each was found; he discusses absolute and relative dating and how archaeologists use coins, pottery, inscriptions, and architectural features for dating purposes. He also describes important centers of civilization in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The volume concludes with a historical review of archaeological research, beginning with the great pioneers like Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy; Arthur Evans, the explorer of Knossos; and William Flinders Petrie, who found that pottery could be used to date archaeological strata.

These informative volumes often tell how things were done, as well as when and why. For example, in Coins of the Ancient World, Yaakov Meshorer, Curator of Numismatics at the Israel Museum, explains how a warm piece of metal was held by tongs and pressed between two dies to stamp out the earliest coins (6th century B.C.) found in Israel. In Underwater Archaeology the authors describe the ingenious technology developed to explore the oceans’ floors—aqualungs, submarines, and a hydrodynamic cradle which tows the archaeologist along the sandy sea bottom while he looks for signs of buried ancient remains.

Introducing Prehistory by Avraham Ronen, tells how the scant physical remains of prehistoric people can reveal how they lived despite the complete absence of written records. Their stone tools are often so distinctive that a prehistoric group can be identified by the form of these tools. The charred wood from their fireplaces is analyzed for radioactive carbon to determine when a site was occupied.

Arthur Siegel in City Planning in Ancient Times examines the earliest examples of city planning in Greece, the Roman Empire, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. City planning began almost as soon as men settled into permanent communities; without planning, cities could be and sometimes were a tangle of twisting streets filled with people and filth. Regardless of their differences, ancient cities commonly had meeting places, markets, theaters, and temples. Archaeologists find these features in city after ancient city.

In Pottery in Ancient Times, Rivka Gonen, curator of the Jerusalem City Museum, discusses how pottery is made, the decorations and finishes that can be applied to it, and how archaeologists use pottery to determine who inhabited an ancient site and when. Ancient sites are cluttered with broken pieces of pottery although most of the other implements made from wood, leather, cloth, and bone, have long since disintegrated. Fortunately for today’s archaeologists, ancient man ate, drank, cooked, and stored almost everything in clay vessels—from cooking oil to cosmetics and drugs.

003

A beautiful example of Mycenean IIIA pottery illustrates a type of pottery which has special significance in Israel and elsewhere in the Near East. This pottery was found in the ruins of El Amarna, an Egyptian city built by Pharaoh Akhnaten in 1379 B.C. as his capitol. El Amarna lasted only seventeen years, so that wherever this distinctive pottery is found in Israel, Cyprus, Syria, and Greece the strata associated with it can be dated to this narrow time frame.

A helpful addition to Gonen’s volume are charts showing various types of Egyptian and Holy Land Pottery. By using these charts the reader can observe the gradual development of pottery shapes.

Rivka Gonen is also the author of Weapons and Warfare in Ancient Times. This book traces the development from prehistory to Roman times of military tactics and military equipment like swords, spears, artillery, and body armor. Swords were not popular with early warriors, mainly because ancient metals were too soft to be used for making long thin blades. By the Roman period, however, metal working had developed to the point that swords became hard and effective. A lightweight Roman sword named the “gladius” was so well-made that when used with a striking motion, it could split open an enemy’s armor, and when thrust, its pointed tip would penetrate almost any target. This popular saber gave its name to “gladiators”—men who fought public battles for sport.

As techniques of fighting and warfare developed, adversaries could fight from far away, rather than man to man. David’s sling was an early long-range weapon, 004one which we know only from the Bible and from some Egyptian and Mesopotamian wall paintings. No archaeologist has ever found the perishable wood and leather of an ancient sling.

Archaeologists have found many examples of ancient jewelry. Renate Rosenthal describes the Jewelry of the Ancient World in a splendidly illustrated volume. The most extraordinary pieces of ancient jewelry are usually found in tombs. In ancient times, the dead were often buried with their most treasured possessions.

Mosaics, like jewelry, are especially beautiful discoveries, colorful relief from the tan, buff, and beige pottery repertoire which is the daily fare of archaeology. The late Michael Avi-Yonah in his volume The Art of Mosaics introduces us to the techniques of mosaic making, and the history of wall and pavement mosaics in the Mediterranean world. In the 4th century A.D., Jewish authorities began to allow the use of representational mosaics in synagogues. At Beth Alpha, at the foot of Mt. Gilboa, a modern Jewish plow inadvertently uncovered a piece of mosaic floor, which on excavation turned out to contain one of the most-well-preserved synagogue mosaics ever discovered. The Beth Alpha mosaic depicts, in strong but primitive style, Abraham about to sacrifice his son Isaac when the hand of God reaching out from heaven, telling him to “lay not thy hand on the lad” (Genesis 22:12).

Dr. Avi-Yonah is also the author of Ancient Scrolls which describes the development of writing. Ancient writing is found on stone, clay, papyrus, copper and lead, and on parchment made from animal skins. The oldest examples of writing come from Mesopotamia and Egypt. The most famous ancient writings are probably the Dead Sea Scrolls. These scrolls, from about the first century B.C. to the first century A.D., were hidden in clay urns and preserved in caves along the shores of the Dead Sea until their accidental discovery about 30 years ago. Part of every book of the Bible has been found in these scrolls except the book of Esther. The non-Biblical scrolls provide the scholar with examples of linguistic usage from the days of Jesus.

After the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, other nearby caves were systematically explored. In one of them, a remote and inaccessible cave, archaeologists found 2nd century A.D. letters from the Jewish general Bar Kokhba who led the second Jewish revolt against the Romans. Apparently this cave was a hiding place for Bar Kokhba’s forces. This cave also contained documents belonging to a woman named Babata, who probably fled to this cave to find refuge from the advancing Romans. From these records we learn about her life and the customs and laws of the times.

Each volume in the Lerner series contains eight pages of color pictures, often strikingly beautiful as in the illustration of the panel of Tutankhamon’s tomb or the photograph of a gold Byzantine medallion. On almost all other pages there are black and white photographs illustrating the text.

At the end of each volume is a glossary of technical terms, although jargon is generally avoided in the well-written text.

Each volume in the series costs $6.95 and may be purchased separately. The publisher is Lerner Publications Co.; 241 First Avenue North; Minneapolis, Minnesota, 55401.

The Lerner Archaeological Series is written for readers twelve and above, but like many well written books for youngsters, this series can be enjoyable and informative to adults as well.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username