032

033

“Unclean! Unclean!”

That cry—the cry of the leper—struck terror into the hearts of passersby in Palestine at the turn of the Common Era.

In medieval Europe that cry separated the leper from everything he or she loved and enjoyed, condemning the leper to a kind of living death.

Today, even well-educated folk grimace at the sound of the word “leprosy” and shrink at the thought of a disease associated with all that is evil and terrible.

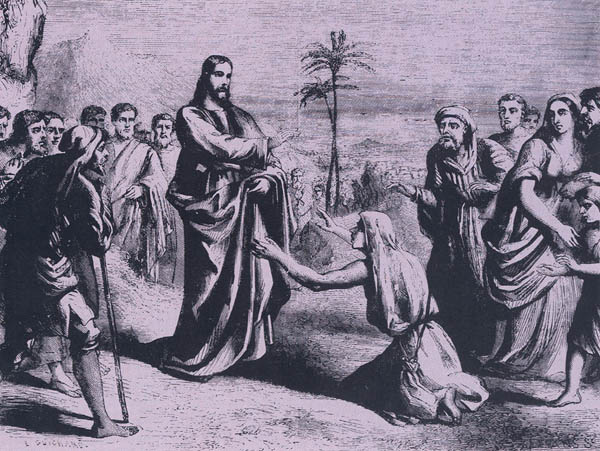

Yet, for most of us, leprosy is either very long ago or very far away. Often it has only biblical associations. We visualize Levitical priests examining people with ancient diseases, or Jesus healing people on society’s fringe—outcasts to both the medical profession and the religious establishment.

If we hear about leprosy today, it is almost certain to be in some foreign land we would be unlikely even to visit. Leprosy is a matter for missionaries and public health officials in tropical countries, if it still exists. Hasn’t it been eliminated by modern science, or at least controlled?

The answer is no!

Leprosy is one of the most widely distributed diseases in our time. It ranks among the ten most common diseases and among the top 20 in numbers of new cases. It is found in at least 140 countries.

Leprosy may cripple as many people as all other diseases put together. There are probably 12 to 15 million cases of leprosy around the world. India alone has more than 3 million.

Because leprosy carries such a terrible social stigma, many cases are hidden. Where compulsory segregation of persons with leprosy has been practiced, patients are very likely to remain secretive about their condition for as long as possible. Some countries are reluctant to acknowledge even the presence, such less the extent, of the disease because it makes their health care systems seem less than adequate, and creates a negative image for tourism, which brings in needed dollars.

In the 1960s and 1970s, articles in both scientific journals and the popular press reported that leprosy had been largely controlled with miracle drugs and public health systems and would soon be conquered. Unfortunately, this turned out not to be the case. With present increases in population and deteriorating health care systems in poor countries, the number of cases may well have increased.

We still don’t know how leprosy is transmitted. Skin contact has always been assumed, and that may be true, but current scientific suspicion centers on the upper respiratory tract (droplets diffused by sneezing, coughing, etc.). Certain foods, animals, even soil, all have been suspected. Epidemics are rare but can occur in small populations where normal immunity is lacking, for reasons yet unknown.

Successful treatment became possible in the 1940s with sulfone drug therapy. Dapsone (DDS) is now the drug of choice in treating leprosy because it is highly effective, inexpensive, readily available and relatively nontoxic. At least five other drugs are also in use, each with its advantages and 034disadvantages (cost, side effects, etc.).

The United States has a small but consistent number of cases of leprosy, probably around 6,000 at any given time. In 1988, 281 new cases were reported. Among native-born American newly diagnosed, most came from four states: Texas, Hawaii, Louisiana and California, in that order. There was at least one new case that year in 29 states; New York had eight and five were found in Illinois.

Until recently, the United States Public Health Service maintained special hospital facilities in two states and 27 outpatient clinics to treat these people, many of whom are immigrants, often poor and uneducated. The current effort is to move such medical care to the private sector.

Of the stigma that attaches to the leper, Norman Cousins has written:

“Today lepers are no longer burned or shot, but popular notions about leprosy have changed very little from what they were in the earliest times. Leprosy is still regarded as more of a curse than an illness; most people would still react in blind horror and superstition if informed that a leper was about to enter the room …. Throughout history, no scourge has been burdened with more superstition and dread than leprosy. To be a leper was to be a candidate for expulsion not just from a community but from human sympathy and grace. [It was] the blackest of all human diseases.”1

The formal name for leprosy today is Hansen’s Disease. In the year 1874, a Norwegian physician, Gerhard Hansen, isolated and identified the organism that causes leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae, a bacillus related to the one that causes tuberculosis.

Contrary to popular superstition, leprosy is one of the least contagious of all diseases; probably 90 percent of people are immune to the disease. With proper precautions, it is most unlikely to spread. Medical and other personnel in regular contact with Hansen’s Disease are not afraid of contracting it. Even among spouses living in close contact, the infection rate is less than 10 percent.

There are several forms of the disease. With tuberculoid leprosy, the body generally develops a significant immunological response to the disease. 035Several years of drug therapy will usually result in a cure.

With lepromatous leprosy, however, the body seems either not to recognize the threat or to be unable to mount an adequate defense. Treatment often requires at least a decade, and sometimes continues throughout the life of the patient.

Between these two extremes, there are three recognizable intermediate forms of the disease, generally called borderline. The five categories are classified by the varying levels of immunity (lepromatous = highest, tuberculoid = lowest). Each type produces a different set of symptoms. These symptoms overlap with each other, and many of them are common to other skin diseases. The variation and overlap of clinical aspects is a major factor in the extreme difficulty of diagnosing leprosy. For example, white patches often occur, but the patches may also be red or brown; sometimes they are scaly, but often not. Unfortunately neither whiteness nor scaliness are diagnostic per se.

Patches on the skin and nodules, or lumps, are the most obvious early signs of the disease. Nerve damage also may take place, although the consequences are not immediately apparent.

Patients are slow to seek help for a number of reasons: Most are unfamiliar with the disease; its onset is generally unobtrusive and relatively painless; the affected areas are mostly anesthetized by associated nerve damage.

Caucasians tend to get the most serious form, lepromatous, or multibacillary, leprosy. Three times as many males as females are known to have the disease, and children are more susceptible than adults.

The source of infection is often unknown because of the long incubation period, generally three to five years, sometimes as long as 20 years.

Without modern medical treatment the disease may be inexorable and its duration without limit. Disfigurement—especially of the face—mutilation, gradual loss of fingers and collapse of the nose are the result.

Little wonder that people react to the disease with horror. Centuries of tradition have developed elaborate social systems to isolate the leper. In the Far East, leprosy is often thought to be a punishment for sexual immorality. In India it is often seen as punishment for an offense committed in an earlier incarnation, and therefore must be patiently endured. Islamic societies also advise patient endurance—the will of Allah does not need to be explained; besides, it gives the faithful an opportunity to acquire merit through almsgiving. In sections of Africa where animistic beliefs persist, leprosy is a mystery, evidence of the spirits’ displeasure, which is beyond understanding.

While details vary, all these traditions identify leprosy with medieval ideas of punishment from the supernatural, which forms the basis for exclusion from human society.

The Bible seems to be the main culprit responsible for this attitude in Western society. People who claimed the Bible as their source of authority made the rules by which the medieval church and society condemned people with leprosy to a living death, sometimes actually performing a burial mass before sending the victim into exclusion. Today it is people who know their Bibles who tend to shudder and shrink when they hear the word “leprosy.”

Yet it would be misleading to blame the Bible for all the problems of stigmatization. Patterns of avoidance and separation exist worldwide. Leprosy has been stigmatized even in places where Levitical rules were not known, much less followed.

The word in the Hebrew Bible that we translate as “leprosy” is tsara‘ath (tsah-RAH-aht). What seems clear is that this term includes a variety of diseases, some serious, some not so serious. This is not surprising when one considers the state of medical science in biblical times. Even today, skin diseases are extremely difficult to diagnose. A physician at the United States Public Health Service outpatient clinic for leprosy in New York City commented that the average patient in the United States may visit as many as 11 physicians before a correct diagnosis is made.2

How tsara‘ath came to be translated as “leprosy” is a story in itself (see the sidebar to this article).

Five people named in the Hebrew Bible had tsara‘ath: Moses; Miriam; the commander of the Syrian army (Na’aman); the servant of the prophet Elisha (Gehazi); and Uzziah, king of Judah. But was it leprosy?

Moses’ case is brief. When Moses asks God what will happen if the Israelites refuse to rally at his call, God gives him some signs. The first is a rod that turns into a snake and then back to a rod. The second involves his hand, which becomes tsara‘ath and then is instantly healed:

“The Lord said to him, ‘Put your hand inside your cloak,’ He put his hands was tsara‘ath, like snow. Then God said, ‘Put your hand back into your cloak’—so he put his hand back into his cloak, and when he took it out, it was restored like the rest of his body—”(Exodus 4:6–7, slightly adapted form NRSV).

Was this leprosy? The miraculous is clearly evident. The snowlike appearance of course suggests 036whiteness. More of this later.

Moses’ sister, Miriam, is struck with tsara‘ath when she objects to Moses’ marriage to a Cushite woman (that is, a black woman). God punishes her in a poetically appropriate manner: Since she objects to Moses’ black wife, He will make Miriam white. The text uses the same phrase as in the case of Moses: Miriam became “tsara‘ath, like snow” (Numbers: 12:10). Moses intercedes with God to heal her. She is excluded from the camp for seven days. In seven days, she is healed—quite quickly! Again, divine will accounts for the disease. Again, the sole stated symptom is whiteness. The cure is unusually quick—seven days. Was it leprosy?

Na’aman, a commander of the Syrian army, we are told, had tsara‘ath (2 Kings 5:1), but it does not seem to have affected his career; he retained his command and his prestige at court. Elisha the prophet gives him this advice:

“Go, wash in the Jordan seven times, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean” (2 Kings 5:10).

After some hesitation, Na’aman takes the prophet’s advice, and he is cured. No symptoms are given here, and the cure seems simple (but miraculous). It is difficult to tell whether or not this is a case of true leprosy.

Elisha’s servant Gehazi secretly asks and receives a fee from Na’aman for Elisha’s medical services. This enrages Elisha:

“The tsara‘ath of Na’aman shall cling to you and to your descendants forever” (2 Kings 5:27).

Gehazi departs, in the now familiar formula, “tsara‘ath, like snow” (2 Kings 5:27). If one of Gehazi’s symptoms was white skin, presumably that was also true of Na’aman. But does whiteness indicate leprosy? Unlike Na’aman, Gehazi’s descendants presumably will also contract the disease.

The last case of tsara‘ath in the Hebrew Bible involves Uzziah, king of Judah (790–739 B.C.). According to 2 Kings 15:5:

“The Lord struck the king, so that he was a m‘tsora [a sufferer of tsara‘ath] ….”

The story of Uzziah’s reign is repeated in 2 Chronicles. Here We learn the cause of Uzziah’s disease: He had attempted to exercise the functions of the priests in the Temple. When the priests objected, Uzziah became angry. Then, suddenly, while the priests looked at him,

“[H]e got tsara‘ath in his forehead! They hurried him out, and he himself hurried to get out, because the Lord had struck him. King Uzziah was tsara‘ath to the day of his death, and being tsara‘ath lived in a separate house, for he was excluded from the house of the Lord” (2 Chronicles 26:20–21).

Here we have a disease that indeed lasts for a long time, although it appears very suddenly. Moreover, the forehead is one of the most common areas for leprosy nodules to appear. This may well be a case of true leprosy.

In Gehazi’s case, as we have noted, the disease attacked not only Gehazi but his descendants. This is also true in the case of Joab. Joab, commander of 037King David’s army, killed Abner, commander of King Saul’s army, in a revenge attack. As punishment, Joab and his descendants would have tsara‘ath (2 Samuel 3:29).

There is an interesting reference to four unnamed people with tsara‘ath in 2 Kings 7. Samaria is under siege, but because of their disease the four have been excluded from the city. The Lord causes the besiegers to flee and the four diseased men discover this. They are thus able to report the good news to their countrymen.

In three of the cases already discussed, leprosy is associated with snow. This is usually taken to mean that the skin turns white. Some scholars argue this proves that these cases of tsara‘ath cannot possibly be leprosy because true leprosy does not turn the skin white. On the other hand, numerous photos in medical texts on leprosy show cases with white patches on the skin. Webster’s unabridged dictionary uses “white scaly scabs” as a description of contemporary leprosy. Collier’s Encyclopedia describes the leper as having “white scaly flat lesions.” Moreover, it may not be so much the white color as the flakiness, or scales, that is referred to in the biblical phrase “like snow.” This distinction is obscured in English translation because the Hebrew is often translated “as white as snow” instead of the more literal—and accurate—“like snow.”

Whiteness is thus a dubious symptom. Scholars who contend that none of these cases can be true leprosy point to other factors. For example, the disease is contagious to the point of exclusion from the community, while true leprosy is only slightly contagious. They also point to the absence of any reference to loss of sensation, wasting away of fingers and toes, or blindness. If these were cases of true leprosy, they argue, we would expect to find references to these dreaded symptoms.3

Of all the specific cases of tsara‘ath reported in the Bible, Uzziah’s seems the most likely to have been leprosy. But a good case can also be made that Miriam too had leprosy:

When Aaron asks Moses to intercede with God to cure Miriam’s tsara‘ath, he begs Moses, “Do not let her be as one dead, of whom the flesh is half consumed” (Numbers 12:12). This certainly sounds like the description of genuine leprosy. And the appearance of the disease on the hands and forehead, as occurs in the cases of Moses and Uzziah, is typical of genuine leprosy. So is the occurrence of it in families, as in the cases of Gehazi and Joab.

Of the 55 uses of tsara‘ath and its derivatives, usually translated into English with some form of the word “leprosy” (leper, leprous), more than half occur in chapters 13 and 14 of the Book of Leviticus. These two lengthy chapters read like an ancient dermatologist’s textbook. Chapter 13 describes the variety of symptoms that can be diagnosed as tsara‘ath. If anything makes it clear that tsara‘ath describes much more than the disease we know as leprosy, this chapter does. Yet the translations persist in using various verbal forms of leprous, leprosy and leper for tsara‘ath, often with footnote explaining the problem. For example, the Jewish Publication Society appends the following footnote to Leviticus 13:3: “A term for several skin diseases; precise meaning uncertain.” Yet elsewhere in this same chapter (for example, Leviticus 13:47) the JPS translators, obviously uncomfortable with this usage of tsara‘ath, translate it “eruptive affection.”

In the Hebrew Bible, the examination of the diseased person is performed by a priest who determines whether the individual (1) can continue in community life, (2) must be excluded from the community as an outcast or (3) is a questionable case requiring temporary isolation and further examination. Symptoms to be evaluated include swelling, eruption and skin spots, all of which may be preliminary indicators of tsara‘ath (Leviticus 13:2). Other conditions that might develop into tsara‘ath include boils (Leviticus 13:18), burns (Leviticus 13:24), itches and scalp conditions. Baldness per se is not an indicator (Leviticus 13:40–41). Hair coloration within the affected part of the skin is important. If normally dark hair has turned white (Leviticus 13:3–4, 10–11, 25), or even yellow, when associated with head or beard (Leviticus 13:30), it is cause for concern and further examination. The depth of the infection or spot can also be critical; tsara‘ath is suspected if “the disease appears to be deeper than the skin” (Leviticus 13:3 and related passages). Another factor is whether there is an opening in the skin; “raw flesh” in the affected area is a positive indicator (Leviticus 13:10, 14–16). Redness or whiteness of the skin is also important (13:18, 24).

Upon reexamination, after seven or fourteen days in questionable cases, the key factor is whether the affected area has spread (Leviticus 13:5–8, 22, 27, etc.).

The technical vocabulary in this chapter is often difficult, and the rules sometimes seem contradictory. For example, whiteness of skin is a bad indicator in Leviticus 13:10, but it is a good indicator in Leviticus 13:4.

Or consider this passage, which seems to contradict so much of the rest of the chapter:

“If the tsara‘ath breaks out in the skin, so that the tsara‘ath covers all the skin of the diseased 038person from head to foot, so far as the priest can see, then the priest shall make an examination, and if the leprosy has covered all his body, he shall pronounce him clean of the disease; it has all turned white, and he is clean” (Leviticus 13:12–13).

In the Revised Standard Version, tsara‘ath is translated “leprosy” in this passage. But, in the New Revised Standard Version, the translators were so troubled at using leprosy here that they translated tsara‘ath as “disease.”

Once diagnosed as tsara‘ath, the individual is subject to a harsh set of rules:

“The tsara‘ath sufferer who has the disease shall wear torn clothes and let the hair of his head hang loose, and he shall cover his upper lip and cry, ‘Unclean, unclean.’ He shall remain unclean as long as he has the disease; he is unclean; he shall dwell alone in a habitation outside the camp” (Leviticus 13:45–46).

The ancients were obviously fearful of contagion. The clothes of the person affected with tsara‘ath were examined, whether linen, wool or animal hide, to see if the clothing had been contaminated (Leviticus 13:47–59). Even a house could contract tsara‘ath.

“If the disease is in the walls of the house with greenish or reddish spots, and if it appears to be deeper than the surface, the priest shall go outside to the door of the house and shut up the house seven days. The priest shall come again on the seventh day and make an inspection; if the disease has spread in the walls of the house, the priest shall command that the stones in which the disease appears be taken out and thrown into an unclean place outside the city. He shall have the inside of the house scraped thoroughly, and the plaster that is scraped off shall be dumped in an unclean place outside the city. They shall take other stones and put them in the place of those stones, and take other plaster and plaster the house.

“If the disease breaks out again in the house, after he has taken out the stones and scraped the house and plastered it, the priest shall go and make inspection; if the disease has spread in the house, it is a spreading tsara‘ath in the house; it is unclean. He shall have the house torn down, its stones and timber and all the plaster of the house, and taken outside the city to an unclean place” (Leviticus 14:37–45).

Chapter 14 of Leviticus deals largely with removing the ritual contamination of someone who has had tsara‘ath. For example, someone who has had tsara‘ath is required to take two clean birds and sacrifice one over fresh water in an earthen vessel (perhaps done by an assistant to the priest). Then the priest dips the live bird in the blood of the sacrifice and sprinkles the blood (into which cedarwood, crimson yarn and hyssop had also been dipped) over the person with tsara‘ath (Leviticus 14:2–9). Various other offerings could remove the ritual contamination. Special provisions are made for the poor who could not afford some of the more expensive rituals detailed in this chapter (Leviticus 14:21–32).

Tsara‘ath is obviously a broad category that included conditions ranging from psoriasis to ringworm and maybe even dandruff. It may well have included leprosy—it probably did. Tsara‘ath was a generic term for many skin conditions used at a time when medical diagnosis was very limited and terminology was very general. Most modern diseases are not named in the Bible, not even those that we know existed at the time.

The cases of tsara‘ath specified in the biblical narratives that we recounted earlier could be leprosy, but none can be definitively diagnosed as such. The miraculous cures are simply that, not diagnostic elements.

Tsara‘ath is consistently associated with impiety in the Bible, and in the stories where its origin is described, it is regarded as a divine punishment. At some point the concern for public health and prevention of the spread of infection, which seems to have been the primary concern of the Levitical regulations, combined with the fear of divine visitation and curses so strongly portrayed in the narrative sections. These two considerations mutually reinforced each other and made the stigma of leprosy so strong that it led to the horrors inflicted in the name of Scripture upon lepers in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Even today, leprosy is very difficult to diagnose in its early stages. It is frequently associated with other skin conditions by competent physicians, so we should not be surprised that the Israelites confused it with other skin conditions, or that the Levitical diagnosis was less than precise.

In the New Testament, there are 13 occurrences of lepra and lepros in six accounts about Jesus.

Jesus cleanses a leper, at his request, by touching him (Mark 1:40–42; Matthew 8:2–3; Luke 5:12–13). Touching a leper was, of course, quite against all accepted customs.

Jesus also eats dinner in the home of Simon the leper in the village of Bethany (Mark 14:3; Matthew 26:6). The eminent Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin has suggested that Bethany was an 039entire village set apart for lepers. According to Yadin:

“[L]epers must have been confined in a separate place east of the city. We know from the Midrash that at this time it was thought leprosy was carried by the wind. The prevailing wind in Jerusalem is westerly—from west to east. Therefore, the rabbis prohibited walking east of a leper. According to the Temple Scroll [one of the Dead Sea Scrolls], lepers were placed in a colony east of the city to avoid the westerly wind’s carrying the disease into the city. In my view, Bethany (east of Jerusalem on the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives) was a village of lepers.”a

When John the Baptist was in prison, he sent his disciples to inquire of Jesus whether He was the “one who is to come.” Jesus replies:

“Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up, and the poor have good news preached to them. And blessed is he who takes no offense in me” (Matthew 11:4–6; see also Luke 7:22–23).

Note that the sick are to be healed, but leprosy is to be cleansed. The latter problem is not just a medical one; it is also a ritual religious problem. The latter condition eliminates one from participation in the religious and social life of the community; one is excommunicated.

This point may be subtly emphasized in another passage (Luke 17:11–19): The lepers approach Jesus at a village entrance, asking for mercy. Jesus tells them to show themselves to the priests. They do—and they are “cleansed”! “Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back” and thanked Jesus. Because he was a foreigner—a Samaritan—the rules of ritual cleanliness perhaps did not apply to this person. That is perhaps why he was “healed,” as opposed to “cleansed.” But he was with a group of lepers, so apparently outcast. This is the only place in the New Testament where leprosy is spoken of as having been healed rather than cleansed.

By New Testament times, the Greeks already had a term for true leprosy—elephantiasis Graecorum. The New Testament probably uses lepra because the writers read the Scriptures in the Septuagint, which used lepra for tsara‘ath. That some of the lepers referred to in the New Testament had leprosy is possible, but again it is uncertain because no clinical descriptions are given.

In the Byzantine period, xenodochia (ZEN-oh-DOH-kee-uh) were formed to care for the unfortunate, the strangers, the poor and the sick, including lepers. Joseph Zias of Israel’s Antiquities Authority has found skeletal evidence of leprosy at Byzantine 062monasteries in the Judean desert.4 Perhaps these monasteries were leper asylums.

Medieval Europe regarded leprosy as a major medical and religious problem. Laws were often passed to control the actions of those infected, generally aiming to isolate them. How strictly the laws were enforced is not known.

Medieval Christians responded to leprosy in two very different ways. Some saw leprosy as a special opportunity or Christian charity and service. Lazar houses, or lazarettos, appeared by the dozens through the British Isles and on the continent. (Leprosy was regarded as the disease of Lazarus in Jesus’ parable in Luke 16:19–31) People with other diseases were also housed in these institutions. Caring for lepers had strong religious appeal, based on the example of Jesus; some Christians became saints through their work with lepers.

Most people however, responded with some of the most in inhumane actions ever perpetrated in the name of God. Persons presumed to be infected (diagnosis was uncertain at best) were declared to be unclean and outcast, forced to carry bells and clappers to warn off anyone approaching, sometimes having to attend their own funeral mass where they were declared dead before being officially excluded from social and religious participation.

The tradition of this stigma has sometimes corrupted the modern understanding of Scripture. When we view biblical accounts through medieval lenses, we misunderstand those stories and carry over that medieval stigma to persons with leprosy today. Those infected with Hansen’s Disease are not lepers (victims, objects of divine punishment, to be outcast and rejected); they have merely contracted a disease we call leprosy, caused by a bacillus similar to the one that causes tuberculosis. In no way do they constitute a threat, medically or socially. They simply need medical care and human understanding, as do all who suffer from disease.

Thanks to A. Dean McKenzie for photo research help.

“Unclean! Unclean!”

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

F.C. Lendurm, “The Name ‘Leprosy,” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1:6 (1952), pp. 1001–1004.