A biblical atlas contains maps showing hills, valleys, cities and villages mentioned in the Bible, but how are the locations of these ancient places determined? Perhaps an even more important question: How confident can we be of the accuracy of these locations?

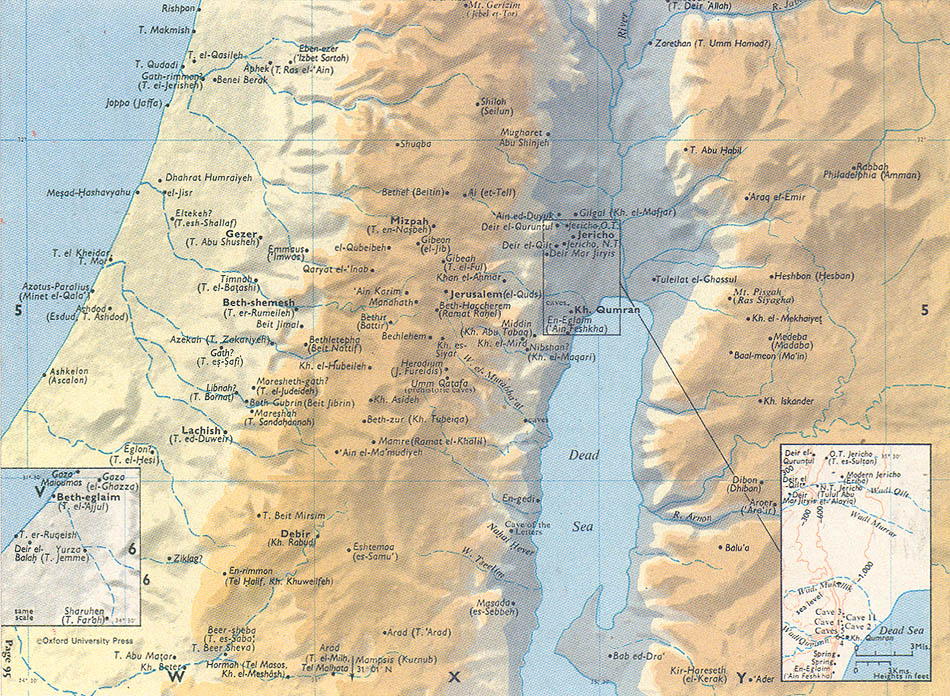

The answer will vary, of course, depending the place involved. Of some biblical locations, we can be very confident. There can be little question, for example, regarding the locations such places as the Jezreel Valley, the Jordan River, ancient Jerusalem, Hebron, Shechem and Megiddo. But other biblical locations are more problematic, especially the many cities and villages that were less prominent in biblical times.

To locate sites of ancient cities, scholars primarily use three kinds of evidence. First, there are ancient written sources, including the Bible, to be taken into account. From the literary sources we learn of the very existence of the ancient cities and their names, and we derive various historical, geographical and topological clues as to their locations. We learn of the existence of ancient Shechem and Megiddo from both the Bible and Egyptian records, for example. It is apparent from the biblical materials that Shechem was located at the foot of Mt. Ebal and Mt. Gerizim. From the Egyptian records, we know that Megiddo guarded the mouth of a pass through the Mt. Carmel ridge into the Jezreel Valley.

Modern Arabic place-names provide a second kind of evidence. Often these names preserve the memory of ancient names. Examples are modern Arabic names such as Beisan, Beitin and Tell es-Seba, which preserves the memory of the names of ancient Beth-shan, Bethel and Beer-Sheba.

The third kind of evidence is archaeological, about which we will have more to say later.

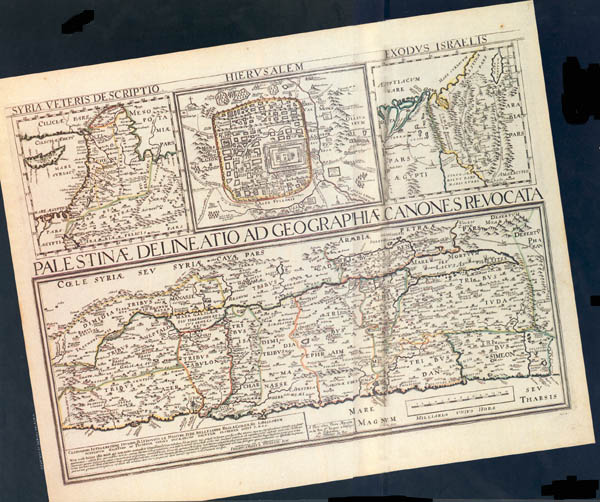

The modern study of biblical place-names may be divided into two phases. The first phase includes the early explorers of the 19th century and the beginnings of modern archaeological excavations around the turn of this century. Since archaeology was still in its infancy then, scholars depended primarily on the first two kinds evidence we’ve discussed—clues from ancient written records and Arabic place-names—in their attempts to establish the locations of biblical cities and villages.

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, who passed through Palestine in 1812 and is best known as the discoverer of Petra, was one of the first to search for connections between the ancient biblical and modern Arabic names. Edward Robinson, a professor from Union Seminary in New York, was the first modern scholar to publish a systematic study of biblical topography and place-names; Robinson often used modern Arabic names as clues to ancient sites. Based on his travels in Palestine in 1838 and again in 1852, Robinson’s study, titled Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea, is one of the classics of modern biblical research. Not only a biblical scholar, Robinson was thoroughly familiar with the other written sources available at that time pertaining to ancient Palestine; moreover, he was accompanied during his travels by a former student, Eli Smith, who was fluent in Arabic.

Limited archaeological information was available to scholars of Robinson’s generation. For example, Robinson himself was unaware that “tells” (artificial hills or mounds) contained layered remains of ancient cities. Standing on et-Tell, the prominent tell between Beitin (biblical Bethel) and Deir Dibwan (biblical Dibon), Robinson observed that et-Tell was the ideal site for ancient Ai. Yet he disqualified it as a candidate because he found no traces of surface ruins from any period:1

“We passed through Deir Dibwan without stopping …. The direction of Bethel is about N.W. by W., and the road leads up from the basin by a hollow way, between a conical hill or tell on the right, and another broader summit on the left. Twenty minutes brought us to the summit of the tell …. We had expected to find here some remains of an ancient site; but there was nothing save a cistern, and immense heaps of unwrought stones, merely thrown together in order to clear the ground for planting olive trees. The position would answer well to that of Ai; and had there been traces of ruins, I should not hesitate to so regard it.”

Et-Tell, we now know, contains the remains of a major ancient city and a later village; it is generally agreed to be the site of biblical Ai.

Gradually scholars came to recognize the significance and stratifed nature of tells. Beginning in the 1890s an ever increasing number of tells were excavated. By the 1920s, ceramic or pottery dating had been developed to the point that the main archaeological periods of the ancient ruins could be determined with reasonable confidence by dating the pottery sherds found in the various strata. Thus, the modern study of biblical place-names entered its second phase. After that, in addition to clues derived from ancient literary sources and modern Arabic names, archaeological evidence often played a crucial role in the process of site identification. George Adam Smith’s masterful study, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, first published in 1894 and last revised by Smith in 1931, presents the status of research at the transition from phase one to phase two.

Archaeological evidence is typically used in two ways in connection with the identification of biblical sites. On the one hand, a ruin that offers no sherds or occupational strata from a particular period may be disqualified as the remains of an ancient city believed to have been occupied during that period. For example, many earlier scholars believed Tell el-‘Areini to be the site of Old Gath of the Philistines. The modern Israeli settlement near the tell was named Qiryat Gat by its founders in this belief. But later, when excavations at Tell-el‘Areini produced no Philistine remains, this proposed site identification had to be abandoned. Current biblical atlases tend to identify Philistine Gath with Tell es-Safi instead.

On the other hand, close correlation between the stratigraphy of a ruin and the history of an ancient city may be regarded as confirming evidence that the ruin represents the remains of the city. Thus, the close correlation between the occupational phases of Tell el-Qedah and what is known from written sources about the history of ancient Hazor seems to confirm that Tell el-Qedah is indeed the remains of Hazor—which had been proposed on other grounds even before the site was excavated.

This second use of archaeological evidence in the process of site identification is essentially the converse of the first: If we do not find surface pottery or occupational debris at a site from the periods during which an ancient city in question would have been occupied according to the written sources, this naturally is seen as negative evidence against a proposed site identification. If we do find close correlation between the archaeological periods represented at the site and the history of the city as indicated by the written sources, this may be taken as confirming evidence for the site identification.

William F. Albright, the late dean of biblical archaeologists, used both of these principles to identify Tell Beit Mirsim, which he excavated between 1926 and 1932, as the site of the biblical city Debir (also called Kiriath-sepher and Kiriath-sennah in Joshua 15:15 and 49, respectively). His conclusion also illustrates that these principles must be used cautiously.

Debir is named in Joshua 10:38–39 among the Canaanite cities conquered by Joshua. Further on in the same book, Debir is mentioned in the brief account of Caleb’s dealings with his daughter Achsaha and in a list of Judean cities.b These references quite clearly suggest that Debir was located somewhere in the hill country south of Hebron. Accordingly, earlier scholars settled on ed-Daheriye, an obviously old village site in the hill country south of Hebron, as the most likely location for Debir. But Albright was convinced that the Israelite conquest of Canaan occurred near the end of the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.) and that Debir must have been a city of some significance when the Israelites conquered it. Failing to find any Late Bronze Age sherds at ed-Daheriye, he rejected its identification as Debir. When no other prominent site in the hill country south of Hebron yielded Late Bronze remains, Albright proposed Tell Beit Mirsim in the Shephelah southwest of Hebron as the most likely site of biblical Debir

Obviously Tell Beit Mirsim did not quite fit the location requirements of Joshua 15, but it was in the general vicinity. Moreover, the results of Albright’s excavations at Tell Beit Mirsim seemed to confirm his theory—at least as he interpreted these results. As Albright himself expressed it:2

“The most decisive argument for the identification is now derived from the archaeological history of our mound, which shows a most perfect parallelism” with the documentary history of Kiriath-sepher (Debir).”

Thus, Tell Beit Mirsim came to be widely recognized among biblical scholars as the ruin of biblical Debir; and this is presupposed in a whole generation of Bible atlases, such as The Westminster Historical Atlas to the Bible, first published in 1946 and still in print.

But it turns out that Albright was wrong in this instance, despite the logic of his reasoning. In the late 1960s, Moshe Kochavi of Tel Aviv University excavated a site called Khirbet Rabud, deep in the hill country south by southwest of Hebron, where he uncovered a clear Late Bronze Age stratum. Thus, following Albright’s own line of reasoning, Khirbet Rabud emerges as a more likely candidate for Debir than Tell Beit Mirsim. The location is right, and it has Late Bronze Age remains as well.

However, the important point is not that Albright apparently was wrong, but that there are serious limitations to archaeological evidence when used in accordance with the two principles described above. There is an obvious danger in using negative evidence—the absence of crucial sherds or occupational strata—since even the most thoroughly conducted archaeological surveys and excavations produce only samplings of data. Crucial sherds or occupational strata sometimes will be missed by accident. We know now that there is at least one prominent site in the hill country south of Hebron that does have a Late Bronze stratum (Tell Rabud). It simply had escaped Albright’s attention.

A basic problem with the second principle—correlation between the stratigraphy of a ruin and the history of an ancient city as confirming evidence for a site identification—is that such correlation may be accidental. Generally these correlations are rather loose, and of course two or more sites in the same general vicinity can have similar occupational patterns.

A more serious and overriding problem with both of the principles, however, is that archaeological evidence often is susceptible to a fairly wide range of interpretation, and our knowledge of the individual histories of most biblical cities is very sketchy; this combination invites circular reasoning. For example, already fairly convinced that Tell Beit Mirsim was Debir, Albright depended heavily on the archaeological evidence seemed from Tell Beit Mirsim in his interpretation of the occasional biblical passages pertaining to Debir. Correspondingly, he was inclined to interpret the artifactual evidence from Tell Beit Mirsim in light of the biblical passages. Thus, it is not entirely surprising that, in the end, he found the archaeological evidence to be in “most perfect parallelism” with “the documentary history.”

Note also the extent to which Albright’s identification of Tell Beit Mirsim as biblical Debir was dependent on his views concerning the nature and date of the Israelite occupation of Canaan—namely, his view that there was a military conquest that proceeded essentially as described in the Book of Joshua, and that this conquest occurred near the end of the Late Bronze Age. Scholars trained in the various techniques of literary analysis and applying their criteria to the biblical materials have long contended that the account of the conquest in the Book of Joshua is a composite and somewhat artificial construct. If so, then any specific date assigned to “the conquest” may be misleading, and the presence or absence of Late Bronze Age remains at Tell Beit Mirsim, Khirbet Rabud, or any other site may be irrelevant for locating Debir.

Not only must archaeological evidence be used cautiously in the process of site identification, but the same is true of the ancient literary sources, including the Bible. Literary analysis reveals that many biblical texts are stratified, with superimposed layers of tradition, not unlike a tell. Accordingly, each text must be carefully analyzed and evaluated with regard to its composition and transmission history before it can be utilized appropriately for purposes of site identification—in the same way that a tell must be excavated and its layers disentangled before its contents can be utilized appropriately.

This point can be illustrated with the case of Numbers 21:21–30 as it relates to the location of biblical Heshbon. This passage recounts how the Israelites, after the Exodus from Egypt and before entering and conquering Canaan from the east, defeated King Sihon of Heshbon. It seems reasonable to identify biblical Heshbon with present-day Tell Hesban in the Transjordan, since Tell Hesban is located at the right place for the biblical references and the modern name seems to preserve a memory of the ancient one. Excavations at Tell Hesban, however, have produced remains of a reasonably impressive Iron Age city—but nothing from the Late Bronze Age.

The absence of Late Bronze Age remains at Tell Hesban poses somewhat of a dilemma for those who take the biblical account of the conquest essentially at face value and date the conquest in the Late Bronze Age. They have proposed that Sihon’s Heshbon may have been at some other site nearby—perhaps Tell Jalul, approximately ten kilometers away, which does have surface pottery from the Late Bronze Age—and that the name Heshbon was transferred later to Tell Hesban.

But scholars who have taken seriously the results of literary critical studies of Numbers 21:21–30 over the past century were not at all surprised with the archaeological findings at Tell Hesban. While literary critics have not always agreed on the details, they have almost unanimously concluded that (a) the narrative portion of Numbers 21:21–30 belongs to a very late, largely editorial stratum of the Pentateuch, and (b) the poem quoted in verses 27–30 belonged originally to some context other than an early Israelite conquest of a Transjordanian kingdom. In other words, literary analysis of the passage had already raised serious doubts regarding its reliability for historical reconstruction. The archaeological excavations at Tell Hesban simply confirmed these doubts.

It is true that literary analysis requires some degree of subjective judgment. And admittedly it is disconcerting when different literary critics working with the same text reach different conclusions, as often happens. But I am not at all convinced that analyzing an ancient text with the methods of source, form, historical and traditional criticism is any more or less subjective than excavating a fifteen-foot square on a tell. Both tasks involve carefully worked out procedures designed to insure objectivity; yet both require judgmental decisions at almost every step of the way. Were it possible for different archaeological teams to re-excavate the same section of a tell again and again over the period of a century, and if the director did not always have the final word in the excavation reports, I suspect that the pattern of general agreement would be about the same as it has been with literary critical research and the Bible over the past century.

True, names do sometimes shift from one site to another over time—this is the main difficulty with relying on modern Arabic place-names for purposes of site identification. A careful study of the name-shift phenomenon is very much needed and possibly would provide principles that would enable us to determine in what circumstances the phenomenon normally occurs.

My own impression is that name-shift occurs mainly in two kinds of circumstances. First, the actual settlement area of a site might move in time, and with it the name. For example, when socio-political changes during the Hellenistic and early Roman periods allowed people to forego the safety of walled tells, younger settlements emerged in the immediate vicinities of the old ruins but often kept the old names. Thus, Herodian or so-called New Testament Jericho was essentially a continuation of the ancient city of Jericho and kept the name, but it was located at a slightly different spot than the old tell. Today the name Jericho is preserved in the name of the modern Arab town—er-Riha, but this site is not exactly identical with either the ancient tell of Jericho (now called Tell es-Sultan) or the site of New Testament Jericho (now called Tulul Abu el-Alayiq). A similar situation exists with Beth-shan where the actual ruins of the ancient city (called Tell el-Husn) are located on the outskirts of the modern settlement of Beth Shean, which preserves the ancient name.

Second, the name-shift phenomenon has occurred when an ancient place name is revived artificially and given to a new settlement, as has happened quite often in modern Israel. Thus, modern Arad was named intentionally after biblical Arad, which is to be identified with Tell Arad, about six miles away from the modern city. Qiryat Gat was named, as I mentioned earlier, in the mistaken belief that Tell el-Areini was the ruin of Philistine Gath. Obviously, such artificially revived names cannot be regarded as primary evidence for establishing the actual sites of biblical cities, and in fact can be misleading.

Is it possible then that King Sihon did rule from a Late Bronze Age city named Heshbon (possibly represented now by Tell Jalul) and that the name Heshbon shifted at the beginning of the Iron Age to the site of present-day Hesban? I doubt it—particularly in view of the fact that Tell Jalul is some six miles away from Tell Hesban and seems itself to have continued occupation during the Iron Age. Neither of the normal name-shift circumstances described above would seem to apply. In fact, the whole theory of name-shift with respect to Heshbon sounds to me too much like an effort to preserve the historicity of Numbers 21 in spite of both literary-critical and archaeological evidence, which suggests otherwise.3

I have concentrated here on the three kinds of evidence available for locating the sites of ancient cities—ancient written sources, modern place-names, archaeology—and observed that all three must be used carefully and cautiously. Archaeology represents at best only samplings of silent evidence. The ancient written sources, given the complexities of the process by which they were compiled and handed down through the ages, can be misleading on matters of historical geography. Place-names are known to have moved around in time.

Unfortunately, other factors that have little to do with evidence also enter into the process of site identification and the production of biblical maps. One such factor is the phenomenon whereby a questionable site identification can be transformed gradually into “accepted scholarly opinion,” simply by being repeated often enough in print. Consider for example, the recently proposed identification of Izbet Sartah as biblical Ebenezer. The suggestion was originally made the excavator of Izbet Sartah, Moshe Kochavi.4

“Identification of Izbet Sartah as an Israelite of the settlement period and the period of Judges is not open to question. Its general nature as a small, unfortified settlement, situated on a barren hillside opposite Philistine Aphek, the four-room house, typically Israelite in its layout, and the characteristic silos ‘collared-rim’ pithoi found in the excavations all support this conclusion.

“As the nearest neighbor of Aphek, lying on the road leading up to Shiloh, the site is ideally located as the mustering center of Eben-ezer for the Israelite forces who went forth to battle the Philistine armies assembling at Aphek (1 Samuel 4). The founders were very likely Ephraimite families who pushed westwards to the edge of the hill country and settled the site in the 12th century BCE, not daring to move down into the Yarkon basin through fear of the Canaanites and later the Philistines, who were in control of the plains.”

A detailed examination of the case for identifying Izbet Sartah with Ebenezer would reveal that this identification is far more doubtful than one might conclude from a casual reading of the two paragraphs quoted above.5 The so-called “collar-rimmed” jars and “four-room houses” were indeed typical features of early Iron Age Palestine in general, but not just of the Israelites; so the presence of these jars at Izbet Sartah does not necessarily make it an Israelite village. Moreover, there is reason to question whether Ebenezer was in fact a village where people lived. The one other biblical passage that mentions Ebenezer (1 Samuel 7:12: “Samuel took a stone and set it up between Mizpah and Shen, and named it Ebenezer”) suggests otherwise, and furthermore seems to place Ebenezer deeper in the hill country than Izbet Sartah. The locations of the various biblical Apheks (there are several) is also a disputed question, along with the question of which Aphek is intended in 1 Samuel 7, and on and on.

But I am less concerned here to explore the problems with the Izbet Sartah/Ebenezer identification than to trace the route whereby Kochavi’s suggestion, never examined any further than in the two paragraphs quoted above, has, simply by being mentioned often enough, achieved the status of “scholarly opinion” and is now finding its way onto biblical maps.

In a follow-up article in Biblical Archaeology Review, Kochavi repeated his suggestion regarding the identification of Ebenezer somewhat more strongly:6

“Certainty is usually beyond the grasp of archaeologists—as it is here—but the available evidence does indicate that it is probably Israelite Ebenezer. And we have no alternative candidate which has anything like this support.”

Then in his commentary on Samuel in the Anchor Bible, Kyle McCarter went even further:7

“The location (of Ebenezer) is unknown. One might assume that it ought to be in the vicinity of Aphek, and indeed an outpost of Aphek, modern Izbet Sartah, is now often cited as a leading candidate.”

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor’s guidebook, The Holy Land, seems to have been the first to present the Izbet Sartah/Ebenezer identification as an established fact without qualification. In the entry, under “Izbet Sartah” one reads:8

“Life at Eben-ezer (the biblical name of the site) must have been rather precarious; the Philistines were only 3 km. away and the two nearest Israelite forts were deeper in the hills. Nonetheless, the oval settlement, with houses ranged against the wall, seems to have prospered ….”

Finally, completing the process, Ebenezer is equated now with Izbet Sartah in the new third edition of the Oxford Bible Atlas, also without qualification.9

This is an interesting phenomenon indeed. A proposed site identification, which is problematic to say the least and which has not yet been explored in any comprehensive fashion, nevertheless is finding its way into Bible study aids, including a highly respected Bible atlas.

How reliable then are our current biblical maps? Historical maps, including those that seek to depict Palestine during biblical times, are by their very nature radical oversimplifications of various kinds of primary and hypothetical information. Such oversimplification is necessary for visual presentation. There is an understandable inclination on the part of cartographers to include as many place-names as possible on these maps and, thus, a corresponding inclination to give questionable site identifications the benefit of the doubt. At the same time, space limitations on maps render it difficult to convey varying degrees of exactness and certainty. Inevitably, therefore, biblical maps imply that we know more than we actually do.

Yet it does not follow that our biblical maps and atlases are useless or entirely misleading. On the contrary, they, like commentaries and other Bible study aids, represent the accumulated results of many years of scholarly investigation. The important thing to keep in mind is that these maps represent scholarly opinion. They are the results of biblical and archaeological research, rather than primary evidence of what they assert.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Edward Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine and in the Adjacent Regions (London: Crocker and Brewster, 1874), p. 449.

William F. Albright, The Archeology of Palestine, and the Bible (Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1935), p. 79.

Actually Heshbon/Tell Hesban represents somewhat of a pattern for the “conquest cities.” Also in the cases of Jericho/Tell es-Sultan, Arad/Tell Arad, Ai/et-Tell and Yarmuth/Tell el-Yarmuk—excavations at what appear to be the most likely candidate sites for cities supposedly conquered by Joshua produced little or no Late Bronze Age remains. For a detailed discussion of this matter, see J. Maxwell Miller, “Archaeology and the Israelite Conquest of Canaan: Some Methodological Observations,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 109 (1977), pp. 87–93; and “Israelite Occupation of Canaan,” in J. H. Hayes and Miller, Israelite and Judean History (London: SCM Press, 1977), pp. 213–284.

Moshe Kochavi, “An Ostracon of the Period of the Judges from Izbet Sartah,” Tel Aviv 4 (1977), pp. 1–13.

For a more detailed examination, see Miller, “Site Identification: A Problem Area in Contemporary Biblical Scholarship,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palastina Vereins 99 (1983), pp. 119–129.

Kochavi and Aaron Demsky, “An Israelite Village from the Days of the Judges,” BAR 04:03

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land: An Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1980), p. 210.