How can we discover—or uncover—the Israelite God in the text of the Hebrew Bible? That is the problem scholars refer to as Old Testament theology. A recent book that has created quite a stir in the academy, written by the prominent Old Testament theologian Walter Brueggemann, answers the question in a way that I believe is quite misguided. For Brueggemann, history is irrelevant to this subject. He doesn’t care what really happened; he doesn’t think it profitable to explore the real-life context in which the Israelite God was revealed. His approach is ahistorical.

To find the Israelite God, Brueggemann, of Columbia Theological Seminary, in Decatur, Georgia, would look only at what is said about God: His is an exclusively rhetorical approach. That’s why his new book, Theology of the Old Testament, has the subtitle Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy.1 “What we have in the Old Testament is speech, nothing else,” states Brueggemann. From this bold claim arises the structure of his theology. Brueggemann’s entire book is framed as a “courtroom trial,” in which “the theological substance of the Old Testament [is seen] as a series of claims asserted for Yahweh [the Israelite God].”

The issues raised are important not only to theologians but to every person who takes seriously the religious message of the Hebrew Bible.

The Old Testament world that Brueggemann presents is one of lively debate, where one side argues its point against advocates of a dissenting perspective and issues remain unsettled for lack of recourse to integrative theological principles. The consensus that existed among leading biblical theologians such as Gerhard von Rad and Ernest Wright in the 1950s and early 1960s has given way to a diversity of theological constructs.

Brueggemann insists that “the God of Old Testament theology as such lives in, with, and under the rhetorical enterprise of this text, and nowhere else and in no other way” (emphasis mine). He thus embraces a rhetorical approach that rejects concern for the historical setting of texts and denies the significance of aspects of divine reality apart from their embodiment in biblical speech.

Efforts to shed light on the historical context of biblical texts, Brueggemann says, simply prolong the futile positivistica attempt to establish the meaning of texts by recourse to “scientific” methods. Brueggemann’s solution is postmodernist:b “In principle, the hearer of this text who listens for its theological cadences refuses to go behind these witnesses. This means that theological interpretation does not go behind the witness with questions of history, wondering ‘what happened.’ What happened, so our ‘verdict’ is, is what these witnesses said happened.”

I can agree with Brueggemann that the primary witness (note his courtroom metaphor) to the God of the Hebrew Bible is found in Israel’s testimony. But I find too limiting an approach that dismisses as irrelevant the light shed on that testimony by historians, epigraphists and historians of religion. The light they bring to the testimony clarifies the grounding of biblical religion in the real world of its time.

Brueggemann disagrees. For him, again, “theological interpretation does not go behind this witness…wondering ‘what is real.’” That centuries of archaeological, epigraphic, lexicographic and historical discoveries and millennia of philosophical reflection can be dismissed that facilely is amazing! Let me explain:

Israel, in contrast to the surrounding cultures, presented her God by recounting events she claimed occurred in human history: an Exodus from enslavement under an Egyptian pharaoh; settlement in a land promised by God, which entailed armed struggle with Canaanite kings; self-rule culminating in defeat by foreign kings and loss of nationhood; and return from exile guided by visions of a more democratic government. In these historical events, which involved actual humans within well-defined, concrete settings, Israel claimed that she encountered God. Critical historical research sheds valuable light on these events, even as historiographic and philosophical reflection aid us in grasping the theological meaning of Israel’s testimony. The ancient scribes who preserved the traditions of Israel were claiming that their speech about God was not limited to a rhetorical phenomenon but stemmed from the experience of the divine presence in the stuff of actual human history.

History mattered in Israel’s account of God. So did nature, which is another reason why limiting biblical theology to Israel’s testimony in speech is an approach narrower than Israel’s. Hymnists, prophets and scribes recognized many witnesses besides Israel: “Heavenly beings” are called to “worship the Lord” (Psalm 29); the sun, moon and other celestial bodies are told to “praise the Lord” (Psalm 148); and “all the earth,” we are told, “sing[s] praises to [His] name” (Psalm 66). Since God is present everywhere (Psalm 139), the heavens inspire thoughts of God (Psalm 8), a God whose creativity is seen throughout the works of nature—in the dimensions of the earth, in the regularity of sunrise, in the pouring rain and in the calving of deer (Job 38–41).

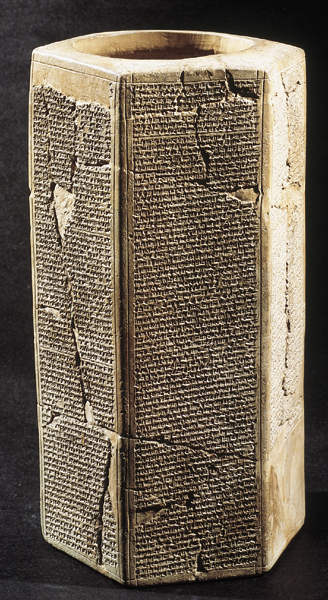

Israel described God by producing an account of her epic history and embellishing it with references to the testimony given by witnesses scattered throughout the universe. What does this say about the biblical theological method? First, it should imply something about research into biblical history. Mythologists and Gnostics are indifferent to historical background. Heirs to biblical faith, by contrast, should be keenly interested in discovering everything they can about the events in which spiritual ancestors discerned God’s presence. The sociology of slaves in New Kingdom Egypt, settlement patterns in Palestine in the period of the Judges (Iron Age I in archaeological terms), Sennacherib’s account of his campaign in Judah, Cyrus’s description of his restoration of peoples earlier subjugated by the Babylonians—all of these contribute to understanding biblical narratives, speeches and hymns.

To denounce research into the historical setting of biblical texts as outmoded positivism is to beat a dead horse. No critical biblical scholars today are so naive as to deny the inevitability of the subjective element in interpretation. For this reason they are deliberate in their efforts to restrain presuppositions, bias and other forms of subjectivity in the honest attempt to hear ancient testimony and weigh the clues left from the past. Indeed, it is the express purpose of graduate programs in biblical studies to equip students with tools designed for that purpose, such as expertise in ancient languages, a grasp of archaeological methodology and an understanding of historiographic and hermeneutical theories. In the last analysis, such tools become effective when participants in scholarly debate recognize that every historical reconstruction invites criticism and revision, even as it contributes to a cumulative tradition of understanding the biblical texts.

I agree with Brueggemann that the confessional testimony of Israel is the starting point of biblical theology, but I disagree with his exclusive focus on the rhetoric of the Bible. Great value lies in ancillary disciplines designed to inform us about the contexts within which Israel’s testimony took shape. Epigraphic, archaeological, historical, social scientific and comparative studies serve to add clarity, depth and precision to our understanding of that testimony.

Theologically, Brueggemann’s exclusively rhetorical focus leads him to a flawed understanding of Israel’s God. Indeed, his description of God could reinforce the unfortunate tendency so deeply rooted in Christendom of contrasting an Old Testament God of wrath with a New Testament God of love.

For Brueggemann, Israel’s God Yahweh has two sides. On the one hand, this God creates, fulfills promises, delivers and sustains—Yahweh is a God Israel can trust. But alas, Yahweh has another side, characterized by what Brueggemann calls his “self-regard.” This self-regard undermines the people’s trust in him. In Brueggemann’s words, “All of these [positive] qualities of Yahweh are pervaded by a hovering danger in which Yahweh’s self-regard finally will not be limited, even by the reality of Israel. One never knows whether Yahweh will turn out to be a loose cannon.” To illustrate the uncertainty that this creates for the Israelites, Brueggemann compares this “hovering danger” to the brooding music in the modern film classic The Godfather: “One has the sense that a violent potential is always present where Yahweh is.”

For Brueggemann, these contradictions are embedded “in the very character of Yahweh.” How, then, is one to relate these contradictory sides of God—on the one hand, the God of steadfast love who honors covenantal promises and, on the other, a God described by Brueggemann as a God of “wild capriciousness,” exercising “sovereignty without principled loyalty,” a God whose “self-regard is massive, savage, and seemingly insatiable,” “an unprincipled bully”? What does one do after one has come to the theological conclusion that “there is a profound, unresolved ambiguity in Yahweh’s life”?

To make sense of these contradictions, Brueggemann proposes a historical division: Yahweh acts in stages, giving vent first to one side of his character and then the other.

But does the Hebrew Bible support this division of God and the consequent assignment of phases of Israel’s history to one side or the other? I think not. Would it not be sounder to attempt to understand the nature of the relationship between God’s wrath and his mercy? Take, for example, a passage from Second Isaiahc in which God speaks to the Babylonians who have destroyed Jerusalem (in 586 B.C.) and led the Israelites into exile:

I was angry with my people,

I rejected my heritage;

I gave them into your hand;

You showed them no mercy.

On the aged you made your yoke

exceedingly heavy.Isaiah 47:6

Brueggemann explains this passage: “There is nothing in this handover to the empire except Yahweh’s passionate, perhaps out-of-control self-regard.” For Brueggemann, this is stage one. When God ultimately shows mercy, this is stage two. This is the rationale behind what Brueggemann describes as the “profound unresolve” in Yahweh.

Should not the biblical theologian rather ask how the author of Isaiah 47:6 saw the relation between God’s wrath and mercy? “Who gave up Jacob to the spoiler, and Israel to the robbers? Was it not the Lord, against whom we have sinned, in whose ways they would not walk, and whose law they would not obey?” (Isaiah 42:24). These words come from the same prophet who heard God announce, “Comfort, O comfort my people…Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her that she has served her term, that her penalty is paid, that she has received from the Lord’s hand double for all her sins” (Isaiah 40:1–2).

Brueggemann understands—or misunderstands—the prophet as explaining the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and the end of the Davidic dynasty by attributing these misfortunes to the fact that “God’s savage self-regard overwhelmed him, and he forgot his covenant promises to Israel.” To the contrary. Second Isaiah, consistent with the pre-Exilic prophets, is interpreting Israel’s history strictly within the terms of God’s covenant, a covenant with reciprocal commitments and obligations. Second Isaiah understands the calamity of 586 B.C. as the consequence of Israel’s flagrant and repeated refusal to uphold her side of the covenant. God’s wrath is not an expression of indulgent self-assertion but of a righteous resolve to prevent humanity’s slide into the chaos of amorality (Isaiah 45:18).

When the prophet speaks of “the heat of [God’s] anger” (Isaiah 42:25), this, too, is an expression of God’s righteousness. When the prophet juxtaposes images of God as mighty warrior and gentle shepherd (Isaiah 40:10–11), he is not describing conflicting, but complementary, sides of God. The same can be said of the blessings and curses in the Book of Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 27–28), Amos’s announcement of judgment against Jeroboam II (Amos 7:10–11), and Jeremiah’s and Ezekiel’s attacks on Temple and palace officials (Jeremiah 22:11–30; Ezekiel 8:5–18). In order to remain faithful to the covenant, God acts in various ways that befit various situations.

Brueggemann offers ample evidence that biblical texts do not present one harmonious picture of God. But rather than see these diverse portraits as proof of a deity of “profound unresolve,” it would seem reasonable to locate each depiction within its specific setting and then seek to understand tensions and paradoxes in terms of the Bible itself (for example, in terms of the covenant) rather than in terms of modern psychological categories like “excessive self-regard.”

Yahweh is the Holy One of Israel. To God, the Holy One of Israel, is owed a kind of fear and obedience to which no other being is entitled. When humans offer pride or sin, instead, it is in the very nature of Yahweh to respond by removing the offense. Holiness and defilement cannot coexist. Moreover, for God to respond to pride and sin with punishment is necessary for maintaining the moral order God has ordained and is a precondition for the planned restoration of shalom, that is, peacefulness and wholeness. The alternative is a lapse into amorality, that is, chaos. In the effort to express God’s holiness as vividly as possible, biblical authors draw on a vast repertory of metaphors and images taken from both indigenous traditions and foreign sources, most of which reflect a worldview that is quite alien to modern thought.

Does Brueggemann capture the biblical meaning of divine holiness with his terms “excessive self-regard,” “wild capriciousness” and “loose cannon”? While fitting the behavior of many Olympian gods and Mesopotamian deities such as Enki and Ninmah, I believe these terms miss the central point in Israel’s development of her concept of God, namely, the moral universe of which that God is author and guardian (see, for example, Hosea 4:1–3). While the repertoire of motifs utilized by biblical authors to describe God is drawn from a wide religious spectrum, such motifs are transformed by the specific environment of Israelite religion.

As with Isaiah, so with Ezekiel. Israel, Ezekiel claims, has flagrantly and repeatedly repudiated God’s commands. The situation is such that God’s holy presence is forced to leave the Temple. “The end is upon you,” Yahweh explains. “I will judge you according to your ways, I will punish you for all your abominations…Then you shall know that I am the Lord” (Ezekiel 7:3–4). For a Benjamin Spock-tutored generation, this is harsh discipline. But does it contradict God’s righteous compassion? No. In biblical thought this is its appropriate expression. Without judgment leading to repentance, God’s promise in Ezekiel 36:33 would have been impossible: “I will cleanse you from all your iniquities, I will cause the towns to be inhabited, and the waste places shall be rebuilt.” The unity of moral purpose intrinsic to Yahweh’s nature is stressed by Ezekiel by concluding this promise of restoration in the same manner as he had concluded the above-cited announcement of judgment, namely with a recognition formula: “Then the nations that are left all around you shall know that I, the Lord, have rebuilt the ruined places” (Ezekiel 36:36).

Does Ezekiel’s juxtaposition of judgment and mercy support Brueggemann’s portrait of a God with excessive self-regard and wild capriciousness? Or is it a statement of divine sovereignty that secures and maintains a moral universe through judgment and mercy, which are understood not dualistically but dialectically, so as to avoid both the reduction of the mystery of the Other and the attribution of arbitrariness and self-contradiction to God? The Book of Ezekiel develops a consistent moral understanding of God: “As I live, says the Lord God, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live; turn back, turn back from your evil ways; for why will you die, O house of Israel?” As for those who attribute divine arbitrariness to God, the divine rebuttal is emphatic: “Yet your people say, ‘The way of the Lord is not just,’ when it is their own way that is not just” (Ezekiel 33:17).

What is true of Isaiah and Ezekiel is true of other biblical writers. When the canon is viewed as a whole—as it ultimately should be by the biblical theologian—it becomes clear that conflicting portraits of God are not simply juxtaposed but are drawn toward a centering moral purpose that no biblical theology should ignore.

I spoke of the importance of avoiding the reduction of the mystery of the Other. With his two stages of a conflicted God, Brueggemann falls into this pit by limiting his theological discussion to the God embodied in the rhetoric of the texts. If the texts portray conflicting views of God, God’s intrinsic nature (his very character) is conflicted. But according to Israel’s own witness, God cannot be confined to human constructions, whether material or verbal. “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” Solomon asks. “Even heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built!” (1 Kings 8:27).

Instead of viewing the speech forms of the Bible as the rhetoric of an ahistorical metaphorical courtroom in which the pros and cons regarding God’s character are presented, we should interpret texts within their concrete settings in the life of Israel. Then we shall see that the conflicting views of God can be traced to the struggling efforts of finite humans to understand the Infinite in their midst.

When, in Haggai 1, God commands Israel to build a house for him and then, in Isaiah 66, rebukes such efforts as forgetting that heaven is God’s throne and earth his footstool, God is not schizophrenic; rather, two groups in Israel are giving expression to two different understandings of God’s will, understandings clearly rooted in their own social and religious location in their community.

The first step in interpretation entails questions about the settings of the text in the social and religious history of Israel. Granted, the process of criticism is ongoing. And no doubt, blunders will be made in reconstructing such settings. But this should not diminish our effort to understand biblical texts within Israel’s historical existence lest a new form of idolatry arise—one that identifies the real God with human constructions.

(This article has been adapted from a longer exposition in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion 67:2 [June 1999].)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Developed in the 18th century, positivism limits sources for acquiring knowledge to data accessible through empirical observation and experimentation.

Postmodernism refutes the claim that reality can be determined by scientific methods and insists that knowledge is the creation of interpreting communities or individuals.