050

051

It is unlikely that any archaeological work will be undertaken at Baalbek in the near future.

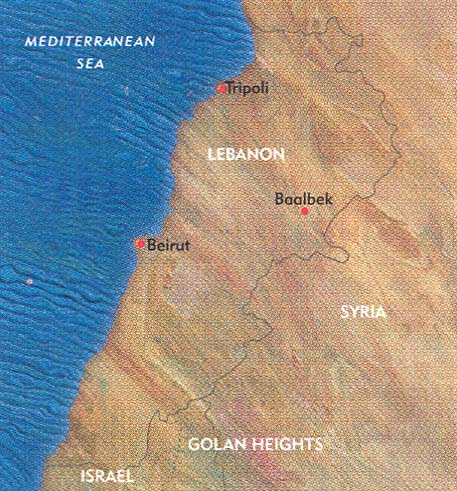

This imposing site lies about 50 miles east-northeast of Beirut (ancient Berytus), between the Lebanon and anti-Lebanon mountains in the Beqa Valley, today home to 30,000 Syrian troops that represent Syrian control of its neighbor. There is much about Baalbek that a modern archaeological excavation could tell us. Excavations have uncovered some Early Bronze Age (third millennium B.C.E.) remains as well as more substantial Middle Bronze Age (about 1700 B.C.E.) remains. But the tell has never been the subject of an extensive modern archaeological excavation. It has been surveyed, photographed, drawn, poked at and sometimes restored but never really dug, so what we know about the site is mostly what has been seen on the surface.

And the surface remains are magnificent: three of the most imposing temples to survive from the Roman period. Their significance, however, arises not from their gigantic size—there are larger temples—but from their bold and unique architecture, which combines Roman, Greek and Near Eastern elements. And what a setting—in a wide, verdant, spring-filled valley over 3,500 feet above sea level, with snow-capped mountains rising another 6,500 feet to the east and the west.

The name Baalbek is composed of two elements: “Baal,” the ancient west Semitic god whose name also means, more generically, lord or owner; and “bek,” which refers to the Beqa Valley. So Baalbek is, literally, the Lord of the Beqa Valley. In ancient times, Baalbek lay astride important trade routes. Two different ancient roads led from Baalbek to the Mediterranean coast—one to Byblos (ancient Jabil) and the 052other to Syrian Tripoli (ancient Trablous). Baalbek was also a major stop on the north-south caravan route from Homs (ancient Emesa) to Damascus in the south. Baalbek was thus a kind of hub for ancient trade between the Mediterranean coast and Syria.

Baalbek’s origins, which go back some two millennia before its floruit around the turn of the era, are shrouded in mystery. We do know, however, that it later became a holy place dominated by temples. Most of our information concerns its temples from the Roman period, after the place had been renamed Heliopolis, the City of the Sun (God), in the late fourth or third century B.C.E. (Don’t confuse this Heliopolis with the Egyptian city of the same name.)

Unlike such sites as Petra and Palmyra (ancient Tadmor), which were largely inaccessible and hidden from view only to be rediscovered by western travelers in the last two centuries, Baalbek was never “lost” in this sense. As early as the Roman period, travelers went there to marvel at its sanctuaries. In the Byzantine period (fourth to seventh centuries C.E.), a church and a basilica were built in the largest of the temple compounds, the Temple of Jupiter. After the Arab conquest in the seventh century, this temple area was transformed into a citadel, complete with mosques. By that time, the name of the site had been changed back to Baalbek after a thousand years as Heliopolis. Even in the Byzantine period, however, coins minted in the city bore the name Baalbek in Arabic letters. In the 11th and 12th centuries, the site suffered from earthquakes and floods (Baalbek lies near the headwaters of two rivers, the Litani River, known in antiquity as the Leontes River, which runs south, and the Orontes River, which runs north).

In his 12th-century Book of Travels, the Jewish wanderer Benjamin of Tudela described his visit to Baalbek,

which Solomon built for the daughter of Pharaoh. The palace is built of large stones, each stone having a length of twenty cubits and a width of twelve cubits, and there are no spaces between the stones … From the upper part of the city a great spring wells forth and flows into the middle of the city as a wide stream, and alongside thereof are mills and gardens and plantations in the midst of the city.

In 1260 the Mongols arrived in Baalbek. They destroyed the mosques and plundered the ancient remains. By the 16th century, the site was again in Arab, more specifically Mamluk, hands. Some of the finest architecture in the surviving fortress comes from this period.

In 1751 two English noblemen from the London-based Society of Dilettanti visited the site. Robert Wood and James Dawkins had a thirst for knowledge and a love of the ancient world. They brought with them an Italian artist named Borra. They did not excavate, but they did survey the site—very precisely. And Borra made a number of magnificent, as well as instructive, drawings of the remains. In 1757 their report was published with 46 plates of Borra’s drawings. The book was an immediate success and was soon translated into several European languages. In large part as a result of the influence of this book (and another like it on Palmyra), European nobility began to build palaces and gardens based on classical models. Late-18th-century churches and even urban complexes testify to the widespread adoption of this neo-classical style.

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, the first westerner to reach Petra (in 1812), visited Baalbek in 1810, but his diaries add little to what was already well documented.

The most talented of the artists to visit Baalbek was, of course, David Roberts, who went there in 1839. Impressive as his famous paintings were, in his diary he confesses that it was difficult to capture the glory of the site in art (see David Roberts’ painting of stone doorway).

In 1898 a visit by German Kaiser 053Wilhelm II renewed interest in the site, leading to a decision to undertake a comprehensive archaeological excavation. The Kaiser agreed to finance it. Work proceeded from 1900 to 1902.1 The two main temple complexes (dedicated to the gods Jupiter and Bacchus) had been turned into fortresses, so the Germans removed these to better expose the temples. But first the fortresses were meticulously documented and photographed. Parts of the temple complexes were then restored with great sensitivity. Areas in danger of collapse were consolidated.2

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the Lebanese government put together a comprehensive plan to excavate not only the temple complexes but also the ancient city. In 1975, however, civil war broke out in Lebanon, putting an end to the project.

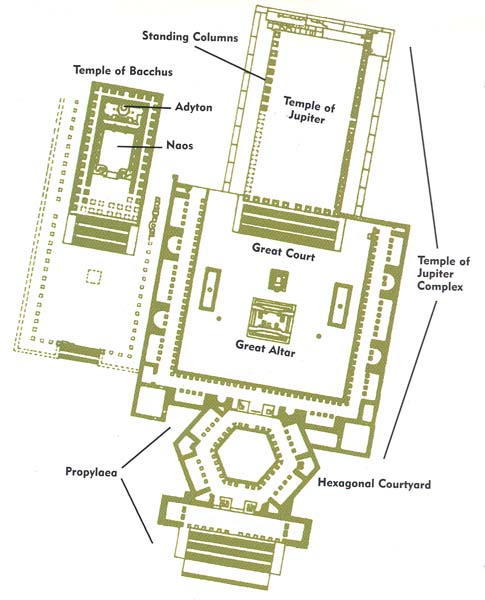

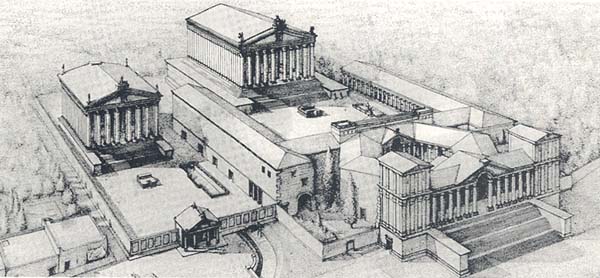

Of the three temple complexes at Baalbek, the largest is centered on the Temple of Jupiter. Adjacent to it is the second complex, the Temple of Bacchus, which is the best preserved. The third complex actually housed two temples, one to Venus and one to the Muses, but we know about the Temple to the Muses only from inscriptions; the temple itself has never been excavated.

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E., his extensive empire split into two major parts, the Ptolemies in the south and west and the Seleucids in the north and east—and they were often at each other’s throats. The beginnings of the Temple of Jupiter may go back as early as 200 B.C.E., when the Seleucids wrested control of the region of Lebanon from the Ptolemies. Excavations under the podium of the great temple revealed segments of construction dating to that time. That there was a Temple of Jupiter here in 60 C.E. is substantiated by a dedicatory inscription from the reign of the Roman emperor Nero. The emperors Trajan and Hadrian visited the temple in the first two decades of the second century C.E.

The Jupiter compound consists of four elements: First, we come to a semicircular plaza with an oval contour, enclosed by a wall lined inside with benches. In this courtyard were many pedestals that once doubtless held statues.

Next comes the propylaea, or entrance structure. It is the largest propylaea in the classical world—and perhaps also the most complex. It consists of an outer gate, a hexagonal courtyard and an inner gate. Actually, the outer gate is an independent structure with a broad set of stairs leading up to it. A tower rises on each end of this gateway, which leads into a 100-foot-wide hexagonal courtyard that has no known parallel in antiquity. This courtyard serves as a passageway between the outer gate and the inner gate, which opens into the temple courtyard. In the center of the hexagonal courtyard is a slightly sunken plaza that was once surrounded by a colonnade. Three doorways lead into the hexagonal courtyard, and another three doorways lead away from it through the inner gate into the temple courtyard. The walls of the hexagonal courtyard were once lined with colonnaded exedrae (covered areas open on one side), in which statues were probably set. (At the end of the third century C.E., with Christianity already dominant in the area, the hexagonal courtyard was covered with a dome and converted into the Church of the Virgin.)

The temple courtyard is square, measuring nearly 350 feet on a side.3 On the far side were steps leading up to the temple. On the other three sides were colonnades, in the back of which were exedrae, some rectangular and some semicircular. The outer columns were unfluted and topped by Corinthian capitals. A second set of columns stood in the openings to the exedrae. The exedrae themselves were richly decorated; the semicircular ones were roofed with half-domes made of stone. The temple courtyard, in effect, was surrounded by columns, behind which lay symmetrically arranged rectangular and semicircular spaces.

In the center of the temple courtyard was a large altar, approached by steps. It was over 55 feet high. Oddly, a smaller altar stood behind it, closer to the temple itself. It too was approached by steps and 056was 30 feet high, so it could not be seen as one approached the temple from the inner gate. Indeed, the large altar was not only very high; it was also nearly 70 feet wide. The result is that the altar almost obscures the temple itself. The prominence and design of the altars suggest the influence of the Semitic tradition of a cultic high place in the Roman east. (During the reign of the fourth-century emperor Theodosius, the two altars were removed to make room for a Christian basilica dedicated to St. Peter.)

To the right and left of the altars were large purification pools.

The columns of the enclosing colonnade created a sense of harmony with a play of light and shadow; passages between dusky and sunny areas engendered a sense of richness. The architectural decoration included the whole Hellenistic and Roman vocabulary of forms, including reliefs and statues. In the center were the two great altars and the purification pools. In its day, this was punctuated with the tumult of visitors who overflowed the sanctuary by the thousands.

On the far side of the courtyard, a set of broad steps, matching those of the propylaea’s outer gate, led up to the temple itself, which loomed nearly 120 feet above the courtyard. The temple was built on a huge, imposing podium, which provided a level surface for construction. The podium walls were made of gigantic hewn stones, some weighing close to a thousand tons (that’s two million pounds). They were cut and moved from a quarry about two-thirds of a mile from the site.

On top of the podium was a crepis, a kind of additional stepped podium, on which the temple itself was built and by which it was approached. The risers and treads on the nine-stepped crepis were much higher and deeper than in ordinary steps, so on the entrance side additional steps were inserted into the oversized risers and treads (forming a kind of double step). The crepis was 315 feet long and 185 feet wide, not much bigger than the temple that sat upon it. The temple podium, however, was over 375 feet long and 225 feet wide.

While the podium has survived intact, very little of the temple itself remains. A row of ten gigantic Corinthian columns supported the pediment of the temple facade, nine of which survived until the earthquake of 1759. Afterward only six were left standing. These six columns still stand to their full height and bear the entablature, including architrave, frieze and cornice. The architrave contains three horizontal bands (fasciae). The frieze is decorated with consoles ornamented alternately with bulls and lions. The cornice, which caps the entablature, is decorated with a mass of geometric and zoomorphic figures.

The temple was designed as a peripteron; that is, it was surrounded by columns on all sides. The columns themselves are 65 feet tall and consist of three unfluted drums on Ionic bases topped by Corinthian capitals.

The internal space of the temple was divided into two halls: the entrance hall (pronaos) and the main hall (naos). On the far (western) side of the main hall was a staircase as wide as the breadth of the hall. The staircase led to the adyton, or inner sanctuary, which was raised above the level of the naos. The statue of Jupiter that once stood in the adyton is long gone.

The height of the temple is also impressive. The podium on which it stood is about 40 feet high. The crepis added another 6 feet. The temple itself was over 75 feet high. The total: over 120 feet. Certainly an awesome sight when viewed from the courtyard.

The entire compound, from the propylaea to the back of the temple podium, covers nearly 300,000 square feet. But a number of other classical sanctuaries are larger, including the Artemis sanctuary in Gerasa (360,000 square feet), the Jupiter sanctuary in Damascus (1,300,000 square 058feet) and the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (over 1,500,000 square feet). What distinguishes this temple complex is not so much its size but its eclectic elements—some classical Greek, some Roman, some combined, some eastern and some unique.

This eclecticism may result from the fact that the complex was not built all at once; indeed, construction took place over the course of several hundred years. Parts of the compound were built as early as 200 B.C.E., while the Ptolemies still ruled Baalbek. As previously noted, we know from an inscription that Nero visited the temple in 60 C.E. By the early second century C.E., when Trajan and Hadrian visited, the large altar in the courtyard had been added. In the late second century or early third century C.E., the construction of the extensive array of entrance gates began. These were not completed until the mid-third century C.E. Finally, the oval plaza in front of the gateway complex was added.

The entire compound was oriented east-west, with the entrance on the east. Immediately to the south of this complex was the Temple of Bacchus (or Dionysus), the god of wine and the vine, as well as of fertility, who gave his name to the orgiastic bacchanalia. The attribution of this temple to Bacchus has been questioned by some,4 but it is supported by reliefs on either side of the main entrance depicting a Dionysian procession and a row of figures connected with the Dionysian cult.

Whereas very little of the Temple of Jupiter remains, the Temple of Bacchus has survived almost intact (thanks to its having been incorporated into the medieval fortress) and is now the most impressive structure at the site.

From an architectural viewpoint, the placement of the temple is perplexing. The Bacchus temple complex is actually attached to the Temple of Jupiter complex. This proximity to the larger, more imposing structure naturally had the effect of diminishing the size of the Temple of Bacchus in viewers’ eyes. The Temple of Bacchus seems much smaller than its larger neighbor, even though it is 85 percent as large.

Clearly, the Temple of Bacchus was designed and built under the influence of its larger neighbor. It is built on a podium on an east-west axis. It is also a peripteron (surrounded with columns). Even the columns are the same: composed of three drums set on an Ionic base and topped by a Corinthian capital. The entablature, too, was fashioned like that of the Jupiter temple: an architrave of three graduated horizontal bands (fasciae); a frieze decorated with vertical consoles, at the top of which are alternating bulls and lions; and a cornice copiously ornamented with geometric and floral patterns. The interior of the temple consisted of an entrance hall (pronaos) and a main hall (naos), with a staircase leading to the adyton (inner sanctuary).

The naos was especially heavily decorated. Indeed, no temple among the extant ruins of the ancient world has a naos as overflowing with decoration as the Temple of Bacchus. This rich decoration is one strong indication that the interior of the temple was open to the populace. Among both Greeks and Romans, the temple was conceived of as a house of the gods; believers did not enter the temple itself but remained in the courtyard, observing the rites conducted around the altar in front of the temple. Greeks and Romans therefore invested most of their efforts in decorating the outsides of their temples. Inside the main hall (naos) stood only a statue of the god. At times, the doors would be opened so the faithful could peer inside at the statue, bathed in the sunlight flooding through the open door. The Bacchus temple, however, differed in having the richness of its architectural ornamentation inside the main hall. The half columns attached to the wall, the niches (in some of which statues were certainly placed), the entablature above the half columns, and the front of the inner sanctuary (adyton) created an exciting richness that invited believers to enter. Two successive staircases led into the inner sanctuary of the temple. The first one extended across the entire width of the naos, with two stone balustrades dividing it into three equal parts. The second led between two pillars, connected by a Syrian gable-like structure, to the raised platform where the statue of the god stood.

The facade of the adyton was designed like a temple. The faithful, who stood in the naos facing the sanctuary, saw two strong pillars decorated with half columns—a continuation of the ornamentation of the long walls of the naos.

That the adyton was constructed like a temple, a kind of temple within a temple, strengthens the contention that the naos was meant for the faithful and was not just the abode of the god. The gathering of the faithful in the closed space of the naos imparted to the religious ritual a much more intimate dimension.

The temple complexes at Baalbek once included two other temples, one to Venus (the Greek goddess Aphrodite) and one to the Muses. The latter, as noted earlier, has never been excavated. It is known only from inscriptions. The Temple of Venus, on the other hand, is in such a superior state of preservation as to be a cause for 060wonder. Although it is only about a hundred feet from its two larger neighbors, it was not used in the Middle Age fortifications, a happy circumstance that largely explains its pristine condition.

Unlike the other two temple compounds, which are oriented east-west, this one is oriented north-south. And the temple podium is an unusual shape. Instead of being rectangular, the back is semicircular, with scallops (semicircular recesses) cut into it.

An impressive stairway consisting of three groups of stairs led up to the entrance facade of the temple. The naos, in conformity with the podium on which it sits, is round except for the entrance side. Round temples were unusual in the classical period (fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E.) but became more common in the Hellenistic period (323–31 B.C.E.). What makes this temple unique, however, is the combination of a straight entrance facade with otherwise rounded walls. In the center of the naos are the remains of a base obviously intended for a statue of the goddess.

But was this temple in fact dedicated to Venus? The only evidence is the shell-like relief decoration, which is reminiscent of her birth from the foam of the sea (the Greek word afros, from which the name of the Greek love goddess Aphrodite is derived, means “foam”). But this is a very tenuous clue, because shell-like ornamentation appears in connection with statues of figures other than Venus. On the outside of the rounded part of the temple wall, for example, are five niches with roofs consisting of half domes; these half domes also contain shell-like decoration. Statues of figures other than Venus were placed in these niches, so it is questionable whether the shell-like decoration here can be used to identify the temple as dedicated to Venus. Nevertheless, Venus is not a bad guess. Jupiter, Mercury and Venus formed a trio known as the Heliopolitan triad. Since there was a temple to Jupiter and a temple to Mercury (the latter on a hill in the southern part of the city; see endnote 4), it seems logical to identify this temple with Venus. Moreover, it is not difficult to see a certain feminine aspect in the design of this temple—it is both small and delicate, especially compared with its two larger neighbors. One even gets the impression that the architect wanted to have some fun with the various parts of the structure, to leave his special stamp on its more routine components. The temple seems in perfect equipoise, balancing 061forces that draw it down toward the earth against forces that lift it up to the heavens. It is difficult to determine the exact secret of its charm.

The temples of Baalbek had considerable influence in late antiquity. This influence is easily seen in numerous sanctuaries throughout Syria and Provincia Arabia. The Baalbek temples, neither Roman nor Greek, are Near Eastern creations that derived inspiration from many traditions, including, obviously, the classical world. All three temples have classical forms; nevertheless, they also have a local eastern character, manifested principally in an eclectic, bold and free use of various stylistic elements and the absence of any consideration of the classical scale of values regarding the interrelationships of a structure’s various components.

The construction methods, too, are local and traditional. The use of huge hewn stones for building was already anachronistic in the Roman world of the first centuries of the Common Era. At a time when large bathhouses were being constructed with cement casting throughout the empire, the builders at Baalbek preferred the use of gigantic hewn stones. Incidentally, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and the Jupiter sanctuary in Damascus were also built with huge stones.

The Baalbek temples are also different in another way—in the marvelous balance between outside and inside. This reflects a very significant change in values. In the Greek and Roman world, the temple was the residence of the god; the community of believers was not allowed inside. Thus the most elaborate designs in Greek and Roman temples are found on the outside, especially the facade. This is not the case with the temples of Baalbek. The broad, convenient staircases at the front of the temples made it easy to ascend; the faithful could enter the large halls overflowing with statues and watch the ritual ceremonies performed in the adyton. At Baalbek, believers felt a proximity to the god: They stood together with the deity under the same roof.

The temples of Baalbek are thus not only magnificent architectural creations. They represent new cultic rituals and, with that, a new way of relating to the divine.

This article was translated by Asher Goldstein.

It is unlikely that any archaeological work will be undertaken at Baalbek in the near future. This imposing site lies about 50 miles east-northeast of Beirut (ancient Berytus), between the Lebanon and anti-Lebanon mountains in the Beqa Valley, today home to 30,000 Syrian troops that represent Syrian control of its neighbor. There is much about Baalbek that a modern archaeological excavation could tell us. Excavations have uncovered some Early Bronze Age (third millennium B.C.E.) remains as well as more substantial Middle Bronze Age (about 1700 B.C.E.) remains. But the tell has never been the subject of an extensive […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

In 1917 two archaeologists, Theodor Wiegand and Karl Wulzinger, carried out additional investigations and published an impressive three-volume work that appear between 1921 and 1925. Archaeological activity of a more limited scope took place between the two world wars, when Lebanon was under French control. The Frenchmen Pierre Coupel and Pierre Anus, along with the Lebanese Haroutune Kalayan, were in charge of these preservation and reconstruction activities, especially at the Bacchus and Venus temples.

It has been suggested that this temple was dedicated to Mercury. I believe the temple to Mercury was located elsewhere, however. In the southern part of the city is a hill named Sheikh Abdallah, on which were seen the remains of a large temple a hundred years ago. Numismatic and epigraphic finds testify to the fact that the Temple of Mercury stood on this spot.