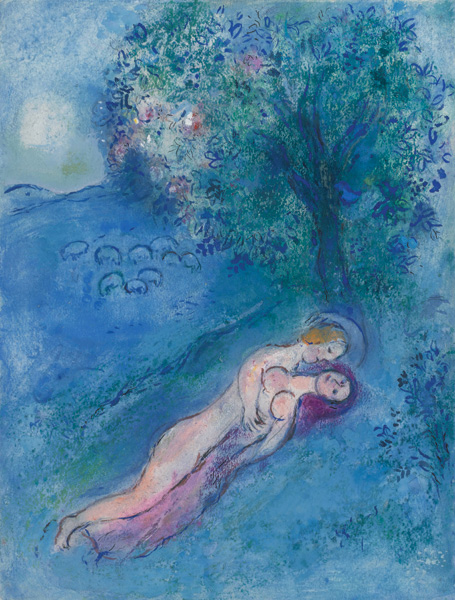

Daphnis and Chloe in the Garden of Eden

050

We often consider how Biblical religions affected one another, but less often how Biblical religions may have influenced what we sometimes call pagan cultures. Indeed, it can be said that by the time Christianity became a licit religion in the fourth century, its narrative was not entirely foreign to the pagans of the Roman Empire.

A case in point is the pagan love story of Daphnis and Chloe, influenced, at least in part, by the Biblical story of the Garden of Eden—and by the intercessory role played by Christ the Son before God the Father.

Written in about 200 A.D. by the Greco-Roman author Longus, who appears to have come from the island of Lesbos, Daphnis and Chloe is a pastoral romance that is overwhelmingly pagan. In his preface Longus dedicates the work to “Love, the Nymphs and Pan.” Other pagan deities appear or are referred to. The protagonists celebrate a Festival of Dionysius, and the god Pan saves the heroine from abduction. But as we shall see, the story also has its Biblical connotations.

Daphnis and Chloe are simple and charming country-dwelling teenagers, the former a goatherd, the latter a shepherdess. They are the adopted offspring of pastoralists who are indentured to a far off Master. They dwell in an idyllic setting and spend most of their days together, trying to decipher the meaning of their love for each other, but have no knowledge of the physical act of love. The pair gambol about, sometimes bathing in the nude, which both pleases and disquiets them. Longus notes: “For there is no remedy for love, no cure to be drunk or eaten, or chanted in spells, 051 052 053 save only kissing and embracing, and lying down naked together.”1 This the pair does, but as Longus remarks, “They had no idea of what comes next, and believed that the pleasure of love went no further than this.”2

Up to this point, the story is entirely in the tradition of the pagan pastoral, buttressed by a charming infusion of naïveté and innocence. The parallel in Biblical terms, of course, is the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden before the Fall. This would be a somewhat obvious comparison even if we knew no more about Daphnis and Chloe, but as it happens the author seeks to resolve the young couple’s dilemma via additional elements from Genesis.

Longus tells us that in the arcadian meadow where the couple often meet, “there stood an apple tree all picked with neither fruit nor leaf remaining; bare were all its boughs, yet one apple still hung ripening atop the very topmost twig, an apple large and lovely, which by itself surpassed the sweet scent of its whole clan … When Daphnis saw it, he made to go up and pluck it and took no notice of Chloe when she tried to hold him back … but Daphnis quickly clambered up the tree and succeeded in plucking the apple and bringing it down as a gift for Chloe.” She is not pleased to receive his gift, however, and he goes on to justify himself: “I am not the one to leave it there that it may fall to earth for browsing beast to trample or gliding snake to poison.”

Daphnis places the apple in Chloe’s bosom, and when he comes close she kisses him. Daphnis is not sorry that he has risked climbing to such a height, for the kiss, we are told, “was better than even a golden apple.”

Although they are somewhat inverted and even confused, all the principal elements of the Genesis story are included. There is of course the tree and the fruit in the Edenic setting. Interestingly enough, here it is the male who takes the apple and tempts the female, rather than vice versa. The serpent, too, makes an appearance, but Daphnis obtains the apple before the reptile can poison it—not quite the diabolical role the serpent plays in the Garden of Eden but ominous enough.

We can deduce that Longus acquired his knowledge of Genesis at some remove and in somewhat garbled fashion. Whether he obtained this at first or second hand, it tends to demonstrate that the stories of the Jews and the early Christians were becoming part of the general cultural inventory of the time.

What immediately ensues draws us further into Biblical analogy. The narrator moves the action to an adjacent garden of great beauty. This idyllic garden, encompassed by a narrow wall of dry stones, is called by Longus, appropriately enough, “Paradise.” The hallowed nature of this paradisical garden is also connoted by the presence of a temple and altar of Dionysius within, a clear example of the commingling of pagan and Judeo-Christian motifs.

The garden is filled with flowers and fruit trees. Longus describes it as “a place of rare beauty and fit to grace the palace of an Emperor.” In fact, it belongs to the absent Master of the place. Word arrives that the Master will arrive to inspect the garden, of which he is very fond, in three days’ time. With help from Daphnis, Daphnis’s foster father, Lamon, who is the garden’s caretaker, strives to ensure that the state of the garden will please the Master.

A cowherd named Lampis now enters the story. He is a disappointed suitor of Chloe, who out of jealousy and spite decides to do all he can to spoil the garden and rob it of its beauty. Waiting for night, he climbs over the wall, uproots the plants and flowers, and tramples on the rest. Then, serpent-like, “he crept away.” Upon discovery of the ruined garden the next morning, there was weeping and great fear of the Master’s reaction. Daphnis and Chloe “tremble and try to hide from his face,” thus echoing the Genesis story which recounts that after eating the apple in the Garden of Eden, “Adam and Eve hid themselves from the presence of the Lord,” their Master (Genesis 3:8).

This is Paradise Lost. Chloe fears that the Master will punish Daphnis for his seeming neglect of the garden by hanging him. There is no way to restore Paradise in time for the Master’s arrival, save by some miraculous intervention. At this point a Christological element enters the story. It is discovered that the Master has a son, named Astylus, who will arrive before the father. When Lamon, Daphnis’s foster father, confesses to Astylus that the garden is a ruin, the latter promises to intercede with the Master on Lamon’s behalf.

The analogy to the intercessory role played by Christ the Son before God the Father is striking. In Christian theology, in the Fall of Adam and Eve, not only the first couple but all mankind have lost Paradise (“In Adam’s fall, we fell all”). The only way to regain Paradise, reserved for the afterlife, is through the intercession of Christ 062 the Son and by the grace of God the Father. These Christological parallels are so glaring that one is astonished that they have not been noted before, either by the monks who preserved the manuscripts or the humanists and scholars who commented on them.

Daphnis and Chloe ultimately consummate their union, but not before experiencing a few minor adventures that are mostly bereft of any further Biblical connotation. Pagan references now abound.

However it is possible to infer one last set of Biblical allusions. Recall that Chloe worried that the Master would hang Daphnis if he was displeased with the state of the garden. Why such a draconian penalty, when a mere reprimand, or at worst a lashing, would do? This can perhaps be explained by a sudden twist in the plot, when it is discovered that the Master is the real father of Daphnis.

We are thus reminded of God the Father’s willingness to sacrifice his son who is hung on a cross, of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac (Genesis 22) and, to a lesser degree, of David’s loss of his beloved son Absalom, who is killed while hanging by his hair from a tree (2 Samuel 18:9–19:1). The stories of Isaac and Absalom are viewed by the Church as precursors and prototypes for Christ’s later sacrifice on the cross. Longus has only partly absorbed and therefore conflated elements of these stories, without fully parsing them. In sum and perhaps without fully realizing it, he is alluding to the belief that it is the sacrifice of the Son, hung on a cross, and the resurrection three days later, that affords the true and deserving Christian a pathway back to Paradise, which Adam and Eve had previously forfeited.

We often consider how Biblical religions affected one another, but less often how Biblical religions may have influenced what we sometimes call pagan cultures. Indeed, it can be said that by the time Christianity became a licit religion in the fourth century, its narrative was not entirely foreign to the pagans of the Roman Empire. A case in point is the pagan love story of Daphnis and Chloe, influenced, at least in part, by the Biblical story of the Garden of Eden—and by the intercessory role played by Christ the Son before God the Father. Written in about 200 […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username