Death in Peqi’in

053

Sometimes archaeologists come face-to-face with a site so unusual that they feel a sense of awe in its presence. That describes our experience upon entering and excavating a mortuary cave in the Galilean hills of northern Israel. Used for burials during the Chalcolithic period (c. 4500–3500 B.C.E.), this cave had been sealed for nearly 6,000 years.

054

One warm spring day in 1995, Fakhri Hasson, the local antiquities inspector in Peqi’in, received an urgent call. During construction of an access road to a new school and an adjacent youth hostel, part of the roof of a cave had collapsed, revealing what appeared to be an ancient tomb. Hasson alerted the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA); and for the next few months, under the auspices of the IAA, we conducted a salvage excavation with the assistance of the Peqi’in Local Council.

What we discovered amounts to a major breakthrough in our knowledge of the Chalcolithic period in the Levant. Among the thousands of bones in this stalagmite cave lay elaborately molded ossuaries,a anthropomorphic sculptures, elegant ceremonial bowls and an ivory figurine. The Peqi’in cache includes artworks reflecting the styles of several different subcultures in Chalcolithic Palestine once thought to have existed in relative isolation from one another.

Peqi’in lies nestled in the western fringes of the Mt. Meron massif, the highest mountain in Israel (nearly 4,000 feet above sea level). The village’s terraced houses, winding streets, abundant grapevines and olive trees are typical of Mediterranean landscapes. Its population is a microcosm of Israel itself, with Druze, Greek Orthodox and Muslim communities living alongside a tiny Jewish presence—which, as legend has it, is the oldest continuous Jewish settlement, dating back at least 2,000 years to the Roman period. Perhaps the natural beauty of this area, as well as the geologically contorted features of the cave itself, encouraged the Chalcolithic inhabitants to adopt it as a burial ground.

The cave’s original entrance is now completely indiscernible. Since the area around the cave is well populated, our first challenge was to protect the site from potential damage by intruders or curious visitors. The Peqi’in council built a metal door over the hole in the cave’s ceiling; to enter the cave, we had to pass through this door and climb down a ladder. A generator was supplied to power a mechanical lift for hoisting up the artifacts and to run the electric lights. As soon as the lights came on, we could see that the cave held a rich stock of grave goods; yet the finds inside were in total disarray, having been deliberately and violently disturbed not long after the final interments. It took weeks for us to grasp the full extent of the hoard.

Curiously, we found no evidence of the existence of this cave outside the cave itself; not a single Chalcolithic potsherd or broken vessel was found in the adjacent olive grove. It is common to find evidence of an ancient site in the surrounding area; sherds or other finds are generally scattered by animals, human beings, seismic activity or running water. Such evidence often alerts archaeologists to the existence of an ancient site in the first place. This added weight to our inference that the Peqi’in tomb had caved in thousands of years ago, completely sealing the cave.

The cave is about 50 feet long and from 15 to 23 feet wide. Much of its interior is covered by stalagmites, stalactites and other geological formations, such as “macaroni” (small petrified strands that hang from the ceiling), “elephant ears” (thin, wide, tapering outcrops of rock) and flowstone (hardened mineral 055deposits that look like solidified liquid), giving the cave an eerie, cinematic atmosphere. This geologically active environment had disturbed many of the finds, as sediments had accumulated on the artifacts, sometimes completely encasing them. But nothing was more jarring than the sight of elaborately styled ceramic ossuaries and vessels alongside hundreds of bones and skulls peering out from the destroyed burial offerings.

Entered from the east, the cave slopes downward, with the burials arranged on three terraces. We believe that an entrance corridor once led from the face of the hill to the upper terrace (the roof of which was punctured by the construction crew’s pile driver). This terrace, built up with fill material, is supported by a 5-foot-high wall that keeps the fill from crumbling down the cave. The southern half of this upper terrace was carefully paved with medium to large stones and topped with a platform of field stones. Ceramic ossuaries were once placed on this carefully tended platform—probably to hold the bones of the more eminent members of the Chalcolithic community.

Across from the platform, a niche in the north wall contained numerous, scattered, disarticulated bones (bones detached from their skeletons). There were also some 30 skulls and another collection of bones laid out in a more ordered fashion, resembling the procedure of reinterring bones in ossuaries. This niche may have been reserved for the less influential dead, whose lowly status did not merit reburial in ossuaries.

On the slope below this terrace, smaller walls were built to create mini-terraces for ossuaries and burial jars. At the lower end is a poorly constructed retaining wall about 2 feet high, separating this middle terrace from the lowest level. About 25 feet below the level of the modern road, the lowest (and largest) of the three terraces was constructed upon fill material up to a height of about 5.5 feet, creating a level surface over the uneven cave floor.

In a loft-like area just above and to the south of this lowest terrace is another burial space. Since we worked our way down from the highest to the lowest terraces, meticulously cataloguing hundreds of basketfuls of finds, the discovery of this chamber came after we had already been excavating the cave for a month. And what a surprise it was! The room could only be entered by climbing up a slick, wet, collapsed surface and then crawling through a narrow crevasse—so narrow that a burial jar barely passed through the opening. This burial space has been severely affected by geological activity; nearly all the finds had melded with the flowstone, becoming part and parcel of the natural environment. The only way to remove the artifacts was to cut through the stone. So we left the 056chamber intact, unwilling to destroy its contents by excavating them.

By probing the fill material of the three terraces, we discovered that the cave had been used as a dwelling during the centuries prior to the burial phase. Beneath the fill were stone floors and ceramic vessels dating to the Early Chalcolithic period (late sixth and early fifth millennia B.C.E.). The adaptation of this cave from a domestic dwelling to a burial ground was part of an important development that occurred in the latter part of the Chalcolithic period: the appearance of organized mortuary centers. No such centers have been found dating to earlier periods, but in the late fifth and early fourth millennia B.C.E. the phenomenon became common—for example, along the Levantine coast and in the Negev Desert.b This development of elaborate, centralized burial grounds was almost certainly accompanied by new beliefs about death and the afterlife.

In Chalcolithic graves, the deceased was interred with various kinds of burial offerings: cultic items (such as offering bowls), luxury goods, everyday objects (pottery used by the deceased) or objects no longer fit for everyday use (broken tools). These burial goods were probably believed to facilitate the deceased’s entry into the netherworld.

In the Peqi’in cave, we found numerous ossuaries. This is the only known use of secondary ossuary burials so far north of the central coastal plain, the region with which this practice is most commonly associated.

These rectangular, ceramic ossuaries have either a flat base or four or six legs (though one of the ossuaries has eight legs). Some of the ossuaries have separate gable-shaped lids, originally modeled with the box as a single unit and then separated from it with a string when the clay was as hard as leather. By using this string-cut method, Chalcolithic artisans produced lids that fit only specific ossuaries—making it easier for modern archaeologists to match up these lids with their corresponding boxes. Usually small horizontal handles were molded onto each box and its matching lid so that they could be tied together.

What is unusual about these ossuaries is their decoration. The narrow facades of some Chalcolithic ossuaries from the coastal plain are decorated with exaggerated ceramic noses. Although these large noses appear on some of the Peqi’in ossuaries, we also found ossuaries with other anthropomorphic and zoomorphic features: Eyes, hair, beards, noses, ears, mouths and even hands—sometimes supplicating—ornament their facades. Here, also, are some of the earliest examples in ancient Near Eastern art of nostrils and open mouths. These depictions of the human breathing organs may signify the spirit of the deceased.

Molded onto the facades of other ossuaries were female breasts. Are these to be understood as fertility symbols? Or do they simply identify the deceased who was reinterred in the ossuary as female? One ossuary even has a portrayal of two seemingly smiling faces, what we have called the “twins.” Does this ornament indicate that two people were simultaneously reinterred in the same ossuary? We did indeed find ossuaries that contained the bones of more than one individual, though in each case the ossuary lacked its identifying lid.

A surprising burial practice was marked by the 057appearance of skulls placed in finely styled and intricately decorated bowls on trumpet-shaped bases (see photo of trumpet-shaped base). These seem to have been placed beside the ossuary containing the rest of the person’s bones. This personal, individualized attention to the deceased is echoed in what are probably our most unusual finds: carefully modeled, ceramic sculptures of full-featured human heads. The heads were found detached from their original vessels. One may surmise that such treatment was reserved for individuals with high status in the community.

Another common type of ossuary was fired without cutting off the lid. These ossuaries contain an opening, generally at the back, so that bones could be placed inside the box. Their facades, too, are decorated with anthropomorphic or zoomorphic features, occasionally portraying fantastic creatures. On one large ossuary, the Chalcolithic sculptor created a frightful, threatening figure with a full face, upper torso, arms and hands; the hands rest menacingly on the figure’s hips, above the ossuary’s opening. This powerful, grisly figure may represent the authority of the person whose bones found their final resting place in this ossuary. A matching anthropomorphic stand, with features similar to those of the ossuary figure, was probably also associated with this influential person.

With a little more detective work, these ossuaries may provide another important piece of information. We have found no evidence of a Chalcolithic period settlement in the Peqi’in region. So where were the ossuaries manufactured? We do know that they were placed on reed mats during manufacture, since impressions from the mats were left on the bottoms of the ossuaries. From these impressions, it may eventually be possible to identify how the mats were woven and what material was used; in this manner, we hope to trace the mats’, and thus the ossuaries’, center of manufacture.

Not all secondary burials were in ossuaries. Our Chalcolithic morticians also used large jars, many with 060pierced handles for carrying them and smaller handles for attaching a cover. Like the ossuaries, the burial jars were often elaborately ornamented with molded female breasts or painted faces—suggesting that they were used in some ritualistic capacity.

One type of jar found in a number of variations in the Peqi’in cave, made of a dark clay mixed with basalt, is related to contemporaneous jars from the Golan Heights, known for basaltic ceramic ware from the Chalcolithic period. Until the discovery of this cave, only random finds linked the Chalcolithic subculture in the Golan region with other Chalcolithic communities.

The cave also yielded an additional type of burial vessel: high, elegantly molded bowls resting on trumpet-shaped bases with fenestrations (windows cut into the base). These vessels are often decorated with a variety of red painted patterns, reminiscent of Chalcolithic pottery from the northern coastal plain—another indication of the far-flung connections among the Levant’s Chalcolithic peoples. A number of these bowls are ornamented with molded representations of human features. The sheer quantity of these bowls—only ossuaries were more numerous—and their special styling suggest that they served an important purpose in the mortuary practices of the local population. Since they resemble incense stands from much later periods, these fenestrated bowls have traditionally been associated with incense burning, but no conclusive evidence has been found to support this interpretation.c Our excavation suggests another possibility: that skulls may have been placed in these vessels to mark the reinterment of a particularly distinguished individual.

Also scattered about the cave were burial offerings—many of them, like the burial jars and the ossuaries, suggesting a connection with other Chalcolithic sites. We found more than 20 round, coarsely worked flint disks; the disks were all perforated at the center. Although we don’t know how they were used or what they signify, similar disks have also been found at Chalcolithic sites (domestic, not mortuary) in the Golan Heights and the Jordan Valley.

Among the burial offerings were objects made of bronze, such as axes, possibly used for ceremonial purposes, and standards for wooden staffs. The standards are ornamented pipe-like bronze units similar 061to finds from the Cave of the Treasure in the Judean Desert. These were almost certainly considered luxury items during this very early period of bronze smelting and manufacture—especially considering that the Bronze Age was not to begin for another half millennium or so. This is the earliest evidence of bronze working north of the Yarkon basin in the present-day area of Tel Aviv, more than 60 miles to the south of Peqi’in.

We also found stone, violin-shaped figurines, believed to represent the female torso. These exquisite carvings connect Peqi’in with contemporaneous Chalcolithic cultures in the Negev region, where similar violin-shaped figurines have been found. They have been uncovered in especially large quantities in the temple at Gilat, in southern Israel. However, the Peqi’in carvings differ from their relatives in that they were discovered in a burial context; also, one of the Peqi’in figurines was sculpted with breasts on its front, emphasizing the female aspect of its symbolism.

When it dawned on us that we were excavating finds that seemed to tie together several dispersed Chalcolithic subcultures, we immediately thought of the Chalcolithic site at Beer-Sheva, known for its ivory carving. And then, miraculously, a small ivory figurine was salvaged from among assorted smashed vessels. Only the head of this finely carved statuette was found; the body still lies buried in the calcified rubble.

Long before we began excavating the Peqi’in necropolis, the site had been severely disturbed. Some of the damage had been caused by the modern collapse of the ceiling and by the effects of geologic activity, groundwater and subterranean animals.

But human beings were the real villains. Few artifacts remained in their original state. Pieces of smashed ossuaries were strewn throughout the cave. Ossuaries were overturned and their contents dumped onto the cave floor. This violent, deliberate vandalism was not a case of modern antiquities robbing, however; the cave was sealed off during the Chalcolithic period, soon after the final burials were laid to rest. For thousands of years, until a bulldozer accidentally knocked in part of the ceiling, no one could enter the cave. Thus the destruction occurred at a time when the cave was still familiar to the local Chalcolithic population.

Who did it, and why? Were the pillagers of this cave looking for treasure—perhaps for highly valued metal objects (we found very few metal tools and ornaments, given the large number of burials). Or were these ancient vandals rivals of the Peqi’in group, determined to plunder and desecrate their enemy’s sacred burial site?

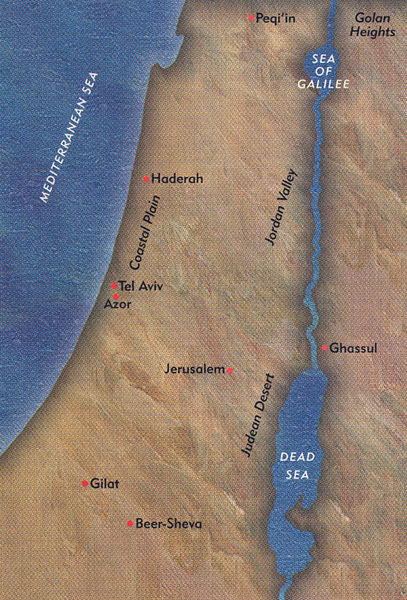

Thus not only the contents of the cave, but even the manner of its destruction, suggest that it was a very important site in its day. The Peqi’in cave is like the hub of a wheel, with its spokes radiating in all directions: east to the Golan Heights and the Jordan Valley, south to the Judean and Negev deserts, west to the coastal plain, and north to Chalcolithic sites on the coast of modern Lebanon. It seems that the deceased who were reinterred in the Peqi’in cave were brought from several geographically dispersed population centers that flourished during this period. Clearly, great efforts were made to transport the bones of the dead to this revered site.

Given the lavishness of many of the cave’s burial vessels and offerings, we would also suggest that this site was reserved largely for esteemed members of a structured and hierarchical society.

Let us take one step further: Is it unreasonable to suggest that this mortuary center may have been administered by a priestly class? Certainly the elaborate burial offerings indicate the existence of a somewhat organized cult, and priests are often important components of hierarchical societies. Someone, or some group, must have built and maintained the cave’s terraces and organized its reinterments; after all, such a confined space would quickly have become overcrowded with ossuaries and jars. How much of a stretch would it then be to imagine some ritual ceremony accompanying the reinterments? Glowing torches, the shadows of fantastically styled burial jars shimmering on the walls, ossuaries passing from hand to hand deep into the inner reaches of the cave—the bones of the dead, the chants of the living.

The excavation was supervised by the authors with the participation of the IAA Northern Region staff. Our thanks to Amir Drori, IAA Director General, who provided the means, financial and otherwise, for the site’s excavation. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Peqi’in Local Council, headed by Nasrallah Heir. All the finds were removed to IAA laboratories, headed by Pnina Shor, for treatment and restoration. The ceramic items were restored under the supervision of Michal Ben-Gal, chief restorer of the IAA.

Sometimes archaeologists come face-to-face with a site so unusual that they feel a sense of awe in its presence. That describes our experience upon entering and excavating a mortuary cave in the Galilean hills of northern Israel. Used for burials during the Chalcolithic period (c. 4500–3500 B.C.E.), this cave had been sealed for nearly 6,000 years. 054 One warm spring day in 1995, Fakhri Hasson, the local antiquities inspector in Peqi’in, received an urgent call. During construction of an access road to a new school and an adjacent youth hostel, part of the roof of a cave had collapsed, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Ossuaries were used for secondary burials. In primary burials, the deceased was simply placed in a permanent grave. In secondary burials, the bones of a corpse were reinterred a year or so after the primary burial. Usually this involved placing the bones in a rectangular box, made of stone or clay, about 2 feet long (the length of the longest bones in the body).

See Claire Epstein, “Before History: The Golan’s Chalcolithic Heritage,” BAR 21:06.