East Meets West

How Greek Art Influenced Monumental Pillars of India’s Emperor Ashoka

038

039

No two artistic traditions seem more unlike than those of India and Greece. The multi-headed, multi-armed figures of Indian sculpture appear to be mystical and cosmic, worlds away from the earthy verisimilitude of ancient Greek statuary.

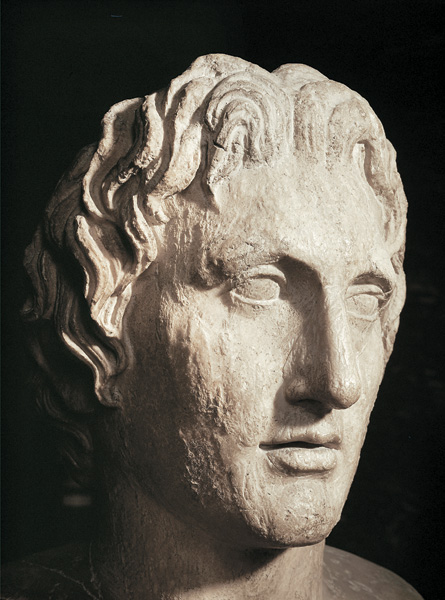

In its early years, however, Indian sculpture was in fact a product of close associations with the West. After the invasion of Alexander the Great in 327 B.C., Greek rule was briefly established in the 040northwestern part of India.a Alexander died in 323 B.C., leaving one of his generals, Seleucis Nikator, in charge of the eastern portion of his domain (the Seleucid Dynasty). In 322 B.C. a man named Chandragupta Maurya, known to the Greeks as Sandrakotos, unified the small tribal states of northern India into the Mauryan Dynasty (c. 322–185 B.C.) and forced the Seleucids out of northwest India.

Chandragupta nonetheless maintained strong relations with the Seleucids (he is even said to have married Seleucis Nikator’s daughter), forming ties that lasted three generations. It was during this period of interaction with the Hellenistic Seleucids that the first monumental stone carvings were erected on the subcontinent (in the Ganges River plain of eastern India), works of art unlike anything ever produced there.b

The large Mauryan carvings were likely inspired by Hellenistic art. The synthesis of Greek and Indian artistic styles becomes clear in the monumental sculptures created during the reign of Ashoka (c. 272–232 B.C.), the third of the Mauryan kings and perhaps the greatest ruler of ancient India.

Much of what we know about Ashoka comes from his Rock Edicts, inscriptions carved on large rocks and cliff faces throughout the subcontinent. These edicts are composed in Prakrit,c the language spoken in many of India’s towns and villages in the third century B.C., and are preserved in several different local scripts. They list the king’s policies and reforms, and attest to his humanitarianism and concern for moral behavior.

One of Ashoka’s most famous edicts describes his conversion to Buddhism following a bloody battle in which his forces conquered ancient Kalinga, in what is now the eastern coastal state of Orissa. In 257 B.C., after defeating the people of Kalinga, Ashoka carved an inscription (Rock Edict 13) on a 4-foot-high sculpture of an elephant, cut into a boulder in the town of Dhauli in northeastern Orissa. The sculpture itself is a dramatic work of art, with the curves of the elephant’s head mimicking the shape of the rock from which it was cut, making the animal appear to thrust forward from its house of stone. In the inscription, the king expresses remorse for the loss of life he caused, and he speaks of his longing for dhamma (dharma), or “righteousness”:

When he had been consecrated eight years the Beloved of the Gods, the king Piyadassi [Ashoka], conquered Kalinga. A hundred and fifty thousand 041people were deported, a hundred thousand were killed and many times that number perished. Afterwards, now that Kalinga was annexed, the Beloved of the Gods very earnestly practiced dhamma, desired dhamma and taught dhamma. On conquering Kalinga the Beloved of the Gods felt remorse, for when an independent country is conquered the slaughter, death and deportation of the people is extremely grievous to the Beloved of the Gods and weighs heavily on his mind. What is even more deplorable to the Beloved of the Gods, is that those who dwell there … suffer violence, murder and separation from their loved ones. Even those who are fortunate to have escaped and whose love is undiminished suffer from the misfortunes of their friends, acquaintances, colleagues and relatives. This participation of all men in suffering weighs heavily on the mind of the Beloved of the Gods.

Buddhist ideas were very much in formation during Ashoka’s time. (The historical Buddha, Siddhartha, lived from 563 to 483 B.C.) During Ashoka’s reign, a gathering of the Third Buddhist Council was held at the Mauryan capital of Pataliputra (present-day Patna). It was decided that missionaries should be dispatched across India, and beyond, to spread the teachings of the Buddha and win converts to the faith. In Rock Edict 3, Ashoka announces that officials would travel throughout the Mauryan empire every five years to instruct people “in the Law of Piety.” In Rock Edict 5, he writes that the job of promulgating Buddhism beyond India’s borders would fall to Dharma Mahamatras (“Officers of Righteousness”). According to 042the edict, “They are occupied with all denominations for the establishment of the Law of Piety and for effecting an increase in conformation to the norm of conduct, as well as for the good and happiness of the virtuous.”

This edict also states that Dharma Mahamatras were sent to the Greek world:

The conquest of piety has been achieved by the Beloved of the Gods here [in India] as well as among all the borderers, even over a distance of six hundred leagues [to where the rulers are] the Greek king named Antiochus, and four [other Greek] kings beyond the said Antiochus, namely Ptolemy, Antigonas, Magas and Alexander.

These Hellenistic kings have been identified as Antiochus II Theos of Syria (261–246 B.C.), Ptolemy Philadelphos of Egypt (285–247 B.C.), Antigonos Gonatos of Macedonia (276–239 B.C.), Magas of Cyrene (300–258 B.C.) and Alexander of Epirus (272–258 B.C.).

During their travels, Ashoka’s emissaries would have come across the great funerary and votive monuments the Greeks sculpted out of stone. They would have marveled at the lions, sphinxes and bulls carved on a scale they had never seen before, and they would have returned to India eager to describe these wonders to their king. Perhaps they even brought back works of art or sketches.

Clearly, Ashoka realized that the 043sculptural techniques used by the Greeks could be adapted to Indian statuary. In this new hybrid style, Ashoka found a perfect medium for giving expression to his new Buddhist beliefs.

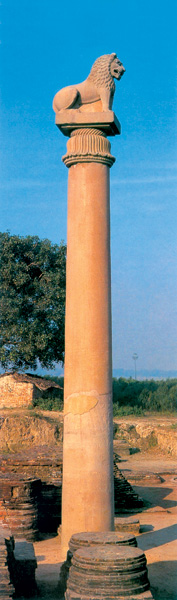

During his reign, Ashoka erected more than 40 tall stone carvings, now known as the Ashokan Pillars, mostly throughout northern India and Nepal (only fragments of about 20 have survived). Ashoka carved edicts on some of these pillars, as he did on rocks and cliff faces. Made of highly polished sandstone, the tallest of the pillars rose more than 50 feet high (such as the pillar at Lauriya Nandangarh, in Nepal), with about a third of the pillar set below ground for structural support. Each pillar was made from two monoliths, one forming the shaft and one the capital. The capital consisted of a carved animal sitting on a circular or rectangular plinth (ledge), which rested on the capital’s bell-shaped base. The two monoliths, capital and shaft, were firmly attached to one another with a large copper dowel.

Many Ashokan Pillars were set near stupas, funerary mounds symbolizing the death and enlightenment of the Buddha. Since Buddhists practiced cremation, they did not bury their dead, but they did bury relics associated with the Buddha or Buddhist saints in stupas. Placed next to stupas, Ashoka’s pillars thus served as monumental markers identifying sacred ground: They were tangible signs of an intangible presence. Eventually, the pillars themselves were worshiped as cult objects.

Ancient Greek funerary monuments frequently took the form of a pillar with a capital surmounted by an animal. Perhaps the most famous examples are the sphinx capitals from the Archaic period, among them the Naxian sphinx (560 B.C.), a 7.5-foot-tall marble sculpture that once stood atop a 33-foot-high Ionic column erected below the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Although the production of sphinx capitals began to die out in Greece toward the end of the sixth century B.C., we know from an inscription on the base of the pillar at Delphi that it was still standing in the fourth century B.C. Ashoka’s emissaries, or other Indian travelers of the Mauryan period, might well have seen this impressive sphinx, crouching on its hindquarters, with its front legs stiffly straight and its wings soaring 045into the air. Or perhaps they saw the very similar sphinx at Cyrene, in modern Libya, a place cited in Ashoka’s edicts as having been visited by his missionaries.

The oblong platform of the Naxian sphinx (not shown) bears a strong resemblance to that of an Ashokan Pillar from the village of Vaishali, in the northeastern Indian state of Bihar (the birthplace of Buddhism and the site of numerous Buddhist holy sites). Crowned by a lion, this pillar rises to a height of 60 feet and is located not far from a stupa.

An extraordinary Ashokan capital topped with a bull (specifically, an Indian humped, or Zebu, bull, a breed apparently known to the Greeks) stands today in the presidential palace in New Delhi, though the pillar was originally erected at a site called Rampurva in northern Bihar. The Rampurva bull resembles Greek statuary in its naturalism, particularly the realistic proportions of its anatomy, as well as the careful artistic attention paid to the animal’s genitals, sculpted so as to suggest a heightened sense of virility.

The plinth of the Rampurva bull is decorated with an anthemion motif—a floral design consisting of lotuses and palmettes. Such motifs were common in Mesopotamia centuries before the Mauryan period. As the British scholar John Boardman has pointed out, however, the manner in which the floral elements on the Rampurva bull were combined was a distinctly Greek conceit, beginning in the latter part of the seventh century B.C. The motif can be seen, for example, on the Erechtheum of the Athenian Acropolis.

Only the plinth survives from an Ashokan Pillar now at the Allahabad Fort in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. The side of the plinth is decorated with a floral design and a bead-and-reel motif—which are clearly indebted to a frieze on the late-sixth-century B.C. Siphnian Treasury building at Delphi.

The plinth of an Ashokan Pillar topped with an elephant from the town of Sankisa, in Uttar Pradesh (the town was strongly associated with the Buddha), is similar to a relief from the Polyandron cemetery in Athens, which was erected for the horsemen killed in the battles of Corinth and Charoneia in 394 B.C. The Polyandron relief features a palmette surrounded by lotuses and rosettes (in a so-called honeysuckle motif), as well as what appear to be lotus buds. The Sankisa elephant replaces the lotus buds with leaves from the sacred pipal (fig) tree, the tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, an example of Indian artists adapting a Greek model for their own particular needs.

The most common type of animal surmounting Ashokan Pillars is the lion, a symbol of royalty and strength frequently depicted in Indian art. (Some pillars feature four addorsed lions, that is, four lions positioned back-to-back.) The historical Buddha, Siddhartha, was closely associated with lions: Called the shakya-simha (“lion of the Shakya clan”), he was said to preach with the roar of the lion.

In classical Greece, too, the lion symbolized strength, and it was often placed on tomb markers (presumably to ward away evil). The lion from the Vaishali pillar, for example, resembles the fourth-century B.C. lion of Amphipolis, in Macedonia, which probably belonged to a large funerary monument dedicated to one of Alexander the Great’s generals. Indians traveling abroad to spread Ashoka’s version of Buddhism might well have been inspired by the striking Amphipolis lion, or others like it throughout the Greek world.

No Ashokan pillar is more beloved in India today than the monument erected in Sarnath (the place where the Buddha preached his first sermon), featuring four addorsed lions roaring from the top of a capital. This captivating image has become the national emblem of the Republic of India, even making it onto the rupee. The lions, representing the four cardinal directions of the compass and symbolizing the extent to which the Buddha’s teachings were to be spread, are Greek in style. But the animals on the plinth of the capital (especially the elephant and humped bull) are undeniably Indian.

Eventually, Indian artistic tradition would grow more distant from Greek models. On the Sarnath pillar, however, an enduring national symbol because of its eloquence, we can still see a fusion of East and West. We see how human creativity can span thousands of miles, how motifs can be absorbed from one tradition into another, transfigured into something glorious and new.

This article is adapted from a paper presented at “Greeks Beyond the Aegean,” a conference organized by the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA) and held at the Onassis Cultural Center in New York City on October 12, 2002. The proceedings were published by the foundation.

No two artistic traditions seem more unlike than those of India and Greece. The multi-headed, multi-armed figures of Indian sculpture appear to be mystical and cosmic, worlds away from the earthy verisimilitude of ancient Greek statuary. In its early years, however, Indian sculpture was in fact a product of close associations with the West. After the invasion of Alexander the Great in 327 B.C., Greek rule was briefly established in the 040northwestern part of India.a Alexander died in 323 B.C., leaving one of his generals, Seleucis Nikator, in charge of the eastern portion of his domain (the Seleucid […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See the following articles in Archaeology Odyssey, July/August 2001: Frank Holt, “Alexander in the East,” and Rekha Morris, “Imagining Buddha.”

Previously, Indian artists had only worked in perishable materials, according to Seleucis Nikator’s ambassador to India, Megasthenes (c. 350–290 B.C.); in a work titled Indika, Megasthenes wrote that India’s monsoon climate encouraged artists to think in terms of the temporary, rather than the permanent.