Emulating Augustus

The Fascist-Era Excavation of the Emperor’s Peace Altar in Rome

038

040

The exquisite Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) stands on a busy Roman thoroughfare near the Tiber River. Carved on the walls enclosing the altar is an elegant relief showing, among other things, a procession led by the emperor Augustus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.). Who would have guessed that this unassuming monument would become the center of scholarly and ideological controversies?

Built between 13 and 9 B.C., the Ara Pacis was dedicated to Augustus by a senatorial decree, commemorating his return to Rome after three years’ residence in Gaul (Augustus spent much of his reign in the provinces). The monument stood on the ancient Via Flaminia (today the Via del Corso), in the area known as the Campus Martius (Field of Mars), and would have been seen by people entering the capital from the north. It is mentioned in the Res Gestae, the list of accomplishments achieved during Augustus’s reign, and representations of the altar appear on coins from the first century A.D.

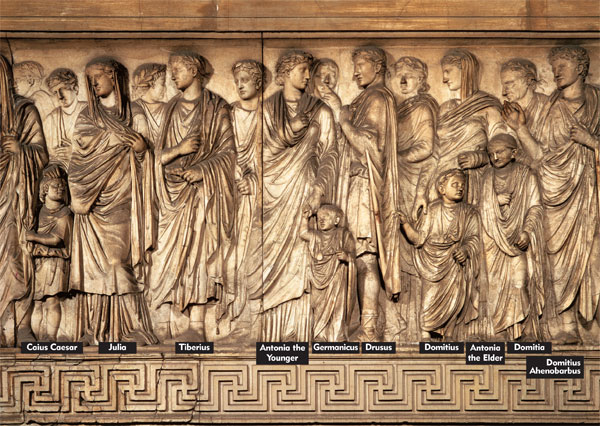

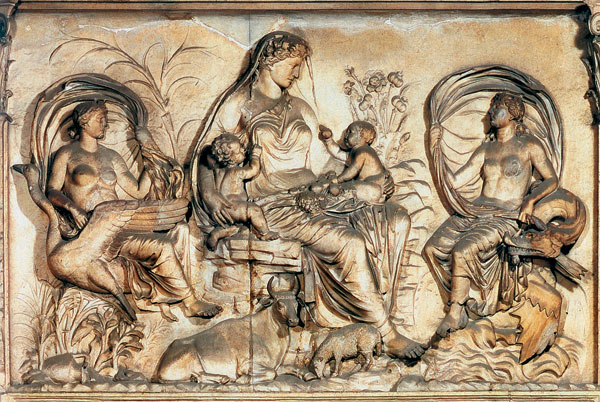

The Ara Pacis monument consisted of 041a U-shaped altar at the center of a nearly square podium (about 36 feet to a side) enclosed by four walls. A doorway in the west wall, facing the Campus Martius, was approached by a staircase with nine steps; the east wall also had a doorway, but no staircase. The exterior surfaces of two of the four walls were carved with scenes of an idealized procession of the imperial family. The other two exterior walls were carved with scenes from the history of Rome as recounted in myth. The interior walls were decorated much more sparsely: The lower portion of all four walls was carved with simple slats, rather like a picket fence; the upper portion of the walls was covered with hanging garlands, bovine-skulls and sacrificial bowls, indicating the sacrificial purpose of the monument.

Fragments of the Ara Pacis were discovered in 1568 during the renovation of the medieval Palazzo Fiano, though no one then could identify the monument. (Indeed, ancient remains often turned up during the construction and renovation of palaces in Renaissance Rome. If one was lucky, the purchase of a certain property would come with a collection of ancient sculpture just beneath the soil.) Over the following three centuries, fragments of the Ara Pacis’s relief sculpture, especially the processional frieze and the mythological panels, made their way into various collections, including the Villa Medici in Rome, the Medici collection in Florence (now the Uffizi), the papal collection in the Vatican and the Louvre in Paris. Although collectors and curators did not know that the fragments were from the Augustan monument, they immediately recognized the high quality of the carving, which prompted one collector to refer to 044the reliefs as “Greek marbles.”

The fragments dispersed among European museums were identified as belonging to the Ara Pacis in 1879 by Friedrich von Duhn, a University of Heidelberg professor who based his identification on evidence from ancient texts and coins. In 1902 Eugen Petersen, then director of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, proposed the first theoretical reconstruction of the monument, after taking photographs of the various parts of the monument and piecing the photographs together into a coherent whole. Petersen’s reconstruction sparked further interest in the plan of the monument.

In 1903 Italian archaeologist Antonio Pasqui resumed excavations at the Palazzo Fiano, where he found fragments of the section of the monument with the portrait of Augustus. Because of the delicate nature of the excavations, Pasqui had to leave a large section of the processional frieze beneath the palace, but he took care to document the find and record the monument’s general dimensions.

The most ambitious excavation at the site came in 1937 and 1938, on the direct request of Mussolini. Under the direction of Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Moretti, excavators were able to remove all remaining pieces of the processional frieze, as well as the decorative elements. Moretti’s goal was to document the precise dimensions of the Ara Pacis so that it could be reconstructed for the Mostra Augustea della Romanitá, an exhibition celebrating the 2,000th anniversary of the birth of Augustus.

Moretti and his team, however, were soon confronted with a number of obstacles, both political and practical. The Italian government had retrieved some, but not all, of the fragments of the Ara Pacis. Problems arose in obtaining a piece belonging to the Vatican (the piece was not officially given to the Italian government until 1954) and a piece in the Louvre, which has never been returned to Rome. Although the French government was willing to repatriate the fragment to Italy, Mussolini declined the offer by saying, “Had I accepted the fragment of the Ara Pacis, the whole French press would have said 045that I would be satisfied with a few stones instead of Tunisia or Corsica.”

The excavations also posed engineering problems, which afforded the Fascist party an opportunity to display their modern engineering savvy. Contemporaneous publications—especially Capitolium, the official state cultural publication—were full of articles lauding Mussolini and the Fascist party for using modern technology and taking bold action to excavate ancient monuments. An October 1938 article in Capitolium praises the engineer Giovanni Rodio’s solution for excavating the Ara Pacis—a solution involving liquid concrete, an enormous steel sawhorse and carbon dioxide.

The section of the Palazzo Fiano resting on the Ara Pacis was heavy and poorly supported. Its walls were cracking from pressure and would have crumbled if the altar had simply been removed. Rodio injected the walls with liquid concrete, brick by brick, until the structure was adequately reinforced.

Then Rodio discovered that the subsoil was full of water, making it impossible to construct a new supporting substructure. So the engineers built a giant concrete and steel sawhorse, which could support the weight of the Palazzo Fiano’s walls. Piers were built to support the sawhorse, with hydraulic jacks between the shafts to allow for adjustment. Also, steel girders were used to reinforce the piers.

With the building supported, the engineers now had to remove the water 047flooding the area. They lay down pipes in a trench along the perimeter of the excavation site, and then pumped carbon dioxide through the pipes, creating a cooling effect that froze the watery earth (similar to the freezing of an indoor hockey rink). The whole operation was a success and all the remaining decorative elements were removed. To this day, only the tufa footings and a few travertine pavement stones from the base remain below the palace.

Rodio’s engineering miracle meant that the Ara Pacis was excavated, reconstructed (largely based on Eugen Petersen’s plan) and put on display in conjunction with the Mostra Augustea della Romanitá. This 1938–1939 exhibition included models, photos and plaster casts of sculpture and architecture, as well as artifacts from the Roman Empire. The celebration was considered an academic success and Mussolini’s most important cultural achievement. In the inaugural speech, the exhibition’s general director, Giulio Giglioli, announced that Romanitá (or Romanness) was the “origin of all” and that Mussolini was the sole protector of this sacred inheritance.

For practical and ideological reasons, the Ara Pacis was placed in a new building next to the Mausoleum of Augustus, in an area commonly known as the Piazzale Augusto Imperatore. This area also included new Fascist office buildings, and thus brought together, in a dramatically symbolic gesture, both Augustan and Fascist monuments.

The exquisite Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) stands on a busy Roman thoroughfare near the Tiber River. Carved on the walls enclosing the altar is an elegant relief showing, among other things, a procession led by the emperor Augustus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.). Who would have guessed that this unassuming monument would become the center of scholarly and ideological controversies? Built between 13 and 9 B.C., the Ara Pacis was dedicated to Augustus by a senatorial decree, commemorating his return to Rome after three years’ residence in Gaul (Augustus spent much of his reign in the provinces). […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username