Oceans cover 71 percent of the earth, and a whopping 97 percent of these waters are beyond the reach of conventional scuba divers, who can reach only about 200 feet below the surface of the sea. The vast majority of the world’s shipwrecks, therefore, cannot be excavated or even found.

Until recently, that is. Archaeologists and marine explorers have now begun to use submarines and new robotic technology to conduct archaeological explorations of the deep waters of the open sea—and they are finding ancient shipwrecks.

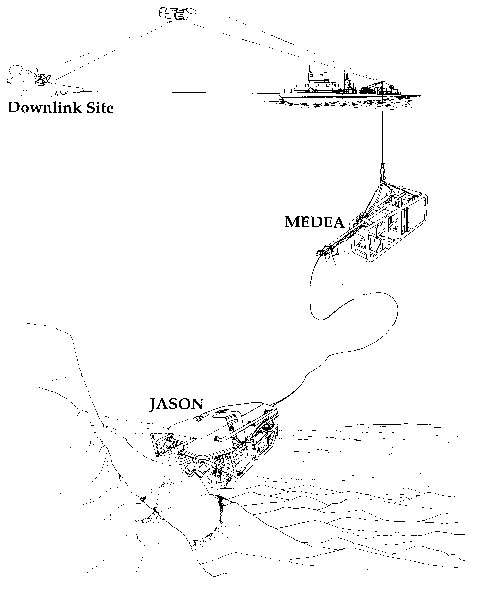

The first deepwater archaeological exploration was conducted in 1989 by archaeologist Anna Marguerite McCann and explorer Robert D. Ballard, a scientist emeritus with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and president of the Institute for Exploration in Mystic, Connecticut.1 Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named Jason,2 McCann and Ballard surveyed the deep sea west of Sicily and north of Tunisia, near a long reef called Skerki Bank that lurks just below the surface. Not far from the swirling counter-currents of the narrow Straits of Sicily, this area is extremely dangerous for navigators. Nonetheless, both ancient and modern shipwrecks found in these waters indicate that this area lay on a long-used trade route over the open sea between ancient Carthage (modern Tunis) and Rome.

At depths of about 2,600 feet, the team surveyed a late-Roman shipwreck, whose visible remains covered an area of about 40 feet by 40 feet. McCann named the ship Isis, after the Egyptian mother-fertility goddess who protected sailors and offered the promise of an afterlife.

Almost all traces of the ship’s wooden hull and any organic cargo above the protective mud of the ocean floor had long been eaten by wood-boring animals. Still, one great advantage of deepwater archaeology is that many artifacts are found unbroken at these depths—for they remain undisturbed by wind, waves or looters. After photographing the site, selected objects were recovered using Jason’s robotic arm. The ship’s chief cargo consisted of large cylindrical Tunisian amphoras—the common terracotta shipping containers of the ancient world. Most of these amphoras once contained oil, while others may have been used to ship garum—the pungent fish sauce made from the fermented guts of fish, so prized by the ancient Romans. Garum brought higher prices than oil or wine, and it was a savory, salty condiment on every Roman table. According to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder (29–79 A.D.), it also cured crocodile bites (Natural History 31.94).

Other amphoras on the Isis contained wine from southern Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. Some of the ceramic common ware used by passengers or crew is from Carthage, the Isis’s last port of call. Examples include a North African red-slip-ware lamp, blackened from its use on board, and a large table amphora with a finely grooved design on its long neck. A millstone used to grind food by hand during the voyage is made of basalt from Libya. The team also found a handmade pot, from the nearby island of Pantelleria, containing pine tar used to caulk the ship—the first example ever found of this common naval material.3

Embedded in the tar was another precious find: a copper coin dropped by an unlucky sailor. William Metcalf, now with Yale University, identified the coin as coming from the reign of Constantius II (c. 355–361 C.E.), the son of Constantine the Great. This dates the sinking of the Isis after the striking of the coin, probably the last quarter of the fourth century, when the political center of the Mediterranean had shifted to Constantinople.a

Based on the deposition of artifacts and the size of the ship’s anchors, McCann estimates that the Isis was about 40 to 50 feet long with a carrying capacity of around 30–35 tons. She could have carried several hundred amphoras. Part of her cargo may well have been wild animals from Africa, which were much in demand for entertainment in the great Colosseum in Rome. The Isis probably also carried textiles, hides, sacks of grain and other biodegradable materials that have disappeared.

The Isis was a sturdy trading ship, built to brave the open seas. Her cargo suggests that she had sailed in the eastern Mediterranean and called at ports in Italy. Where the Isis was heading on her fateful last voyage is unknown, but it seems reasonable to suppose that she was heading toward Rome. Her captain may have been the owner. In the late-Roman period, smaller privately owned merchantmen tended to replace the larger state-financed fleets that had served the empire earlier—largely because the risks were high and smaller ships had less to lose.

A second season at Skerki Bank in 1997 brought to light seven new shipwrecks: four Roman ships, one medieval fishing vessel dating around 1000–1250 C.E., and two wooden 19th-century C.E. sailing ships.4 These wrecks were found with the aid of the U.S. Navy’s nuclear submarine NR-1, whose powerful sonar, once used to track Russian submarines during the Cold War, can spot an amphora at a distance of 3,500 feet.

This second expedition to Skerki Bank produced tremendous technological breakthroughs. Under the direction of Dana Yoerger from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the engineering team made detailed “photomosaics” of the shipwreck sites by stitching together digital images generated by an electronic still camera. In addition, the engineers made very precise bathymetric maps showing the depth of the sea floor and the wrecks’ upper surfaces. This kind of non-invasive “excavation” allows archaeologists to document broad areas of the sea floor without lifting artifacts or damaging the site.

The earliest of the Roman wrecks, designated Skerki D (for Delta), is from the first half of the first century B.C.E. Skerki D’s cargo includes at least 13 different types of amphoras from both the western and eastern Mediterranean. By far the most numerous type is the popular wine jar made by the Sestius family at Cosa, a leading Roman port on the west coast of Italy.b Some of these amphoras may be stamped “SES,” the Sestius family’s trademark. It seems likely, then, that Skerki D was loaded at Cosa before it headed south. These high-necked Sestius jars, with their long handles and solid spiked toes, would have been easily lifted onto a stevedore’s shoulder and efficiently stacked in the hold of a ship. Each held about seven gallons of wine.

A number of wine amphoras on Skerki D, visible in the photomosaic but not recovered, appear to be Greek jars with double-rolled handles from the island of Kos. Wine from Kos was famous, and these Koan jars were imitated by the Romans as they competed in the wine trade.c Some large round jars recovered from Skerki D held olive oil from the Italian Adriatic coast and from North Africa. A wide-mouthed Punic amphora visible in the photomosaic probably contained fruit sauce or pickled fish. Smaller flat-bottomed shapes may have contained beer. Other artifacts recovered include black-glazed pottery from Campania, in Italy, and kitchen ware used in feeding the crew. A bronze pan and a fine long-handled ladle decorated with duck-head finials on its handle must have been intended for an elegant Roman table. Two lead anchor stocks and one lead anchor strap that supported the anchor’s wooden flukes marked the bow at the northern end of the wreck site.

A second Roman wreck surveyed in 1997, identified as Skerki F (for Foxtrot), dates to the mid-first century C.E. It carried a very different cargo. At one end of the ship’s hold were columns and building blocks of high-quality stone, which may be granite from the quarries of Aswan, Egypt. At the other end were stacks of pottery for Roman kitchens: casserole pans, cooking pots, frying pans, sauce pans, bowls and basins. Carefully packed in the hold according to size, this pottery was intended for sale at a market it never reached.d

The amphoras on this ship came from both the eastern and western Mediterranean, including North Africa, Spain and Italy. They contained wine, oil and fish sauce. Three unique, flat-bottomed amphoras of the same form but in graduated sizes were examined by amphora expert Elizabeth Lyding Will. She associates this shape with an example from Pompeii that has a painted inscription indicating that the contents were lomentum. Pliny the Elder describes lomentum as both a blue pigment and a powder made from bean meal (loment) used as a cosmetic, detergent and medicine (Natural History 18.117; 33.89; 33.162). These jars from Skerki F are the first evidence for the export of this product. Analysis of the clay, however, indicates that they were possibly made in North Africa rather than in Pompeii.

Skerki F was the largest and heaviest of the Roman Skerki wrecks. The wreck site is about 70 feet long, suggesting that Skerki F was a medium-sized freighter, but it must have been broader and heavier in the beam to accommodate the load of building stone.

Where was Skerki F going? Considering the weight of the stone cargo, it is likely that after the ship was loaded, probably at Alexandria, it headed west along the North African coast, perhaps picking up pottery at Carthage. The finds from Skerki Bank, especially the cargo on Skerki F, indicate a flourishing trade between the eastern and western Mediterranean in the early Roman empire—a trade that made use of direct routes over open seas.5

The next archaeological expedition in the deep sea occurred in the summer of 1999 when Ballard and a team headed by Harvard archaeologist Lawrence Stager, director of the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, Israel, investigated three shipwrecks in waters close to that ancient port city. The wrecks lie in international waters between the Nile Delta, the Gaza Strip and the southern coast of Israel.

One of the wrecks proved to be from the 19th century C.E., but the other two date to the mid-eighth century B.C.E.—the only Iron Age shipwrecks found so far in the eastern Mediterranean, in either shallow or deep water. Though the two wrecks were separated by a couple of miles of sea floor, they carried cargoes packed with virtually identical amphoras, suggesting that the vessels may have been part of a single flotilla.

About 50 feet long and 25 feet wide, these ships were tubbier than most ancient Mediterranean merchantmen, which typically had a length-to-width ratio of 3:1. Stager estimates that each ship was packed with 300 to 400 amphoras; analysis of the jars’ clay by petrographer Daniel Master indicates that they were made in the central region of modern Lebanon, the heartland of ancient Phoenicia. Many of the amphoras raised from the wrecks were lined with pitch, a means of preserving wine—as in modern retsina. Stager suggests that each ship probably carried about 10 tons of wine.

Both wrecks were equipped with anchors made from dressed stone perforated with a single rope hole. Israeli maritime archaeologist Avner Raban has noted that these are similar to anchors found at the Phoenician colony of Kition on the island of Cyprus. Two-handled cooking pots used to prepare food for the crew were also found on both wrecks. From the stern of one of the ships, an incense burner and ceramic wine decanter with a typically Phoenician mushroom-shaped lip were recovered. Possibly the ship’s crew burned incense and poured libations of wine to appease the gods who controlled the winds and seas that eventually sunk the vessels.

Ballard is now exploring the Black Sea, with archaeologists Fredrik Hiebert and Cheryl Ward. Four new shipwrecks from the Byzantine period have been discovered, three of which were packed with carrot-shaped amphoras typical of north-central Turkey. We are not sure of the jars’ contents, as no amphoras were actually raised from the wrecks. The fourth wreck is unique. It was discovered in the Black Sea’s deepest layer, which lacks oxygen, meaning that the wood-boring animals that eat ships’ timbers cannot live there. The result is a shipwreck that still has its decking intact and its mast standing. We cannot use a ROV to peer into the hold of this ship because its superstructure, eaten away in all other shipwrecks, is still in place!

Investigators are able to document the surface finds of deepwater shipwrecks with great accuracy. Archaeologists then select artifacts to be lifted to the surface for study and conservation. Recently, sonar sub-bottom profiling has been added to the ROV’s tool kit to provide images below the uppermost remains of the wreck. However, we still lack the technology to excavate below a wreck’s uppermost layer.

Judging by excavated shallow-water shipwrecks, such as the one at Uluburun,e and ancient ship manifests, we would expect to find a wide variety of manufactured and raw materials packed in the holds of these deepwater wrecks: copper, tin, lead and iron; glass ingots or cullet (broken or scrap glass suitable for remelting); unworked ivory and precious woods; and ceramic vessels.

Organic and perishable products were also widely distributed by seafarers in antiquity. Linens from Egypt, purple-dyed wool from Phoenicia and silks from China and India were highly sought-after commodities. Herbs, spices, nuts and dried fish were shipped throughout the Mediterranean, as were live animals (depicted on the above mosaic) for food or sport. Moving staples across the deep blue sea became necessary as the capitals of empires—particularly Rome itself—became too large to keep their populace from starving without importing grain and other foods from far-flung colonies.

Emperors and wealthy Romans also coveted art treasures from Greek sanctuaries. The great hope of all marine archaeologists is to discover great statues from antiquity, such as the bronze Greek heroes found in the sea off Riace in southern Italy.6 Since bronzes were often melted down, few ancient examples survive—and most of those the bronzes that we do have come from the sea.

New tools and techniques are currently being designed at Woods Hole to begin excavating beneath the surface levels of deepwater shipwrecks. We shall soon know with certainty what now is only educated guesswork—and, inevitably, surprises await.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

How long ancient coins stayed in use is a matter of debate, but those least in value, like this copper coin, would probably not linger for long. This date matches nicely with the typological dates of the pottery vessels from the wreck, the lamp, and the four late-Roman iron anchors found on the deck of the Isis.

Petrological analysis of two of these wine amphoras by David F. Williams of the University of Southampton identified the clay with an amphora kiln in Albinia, near the port of Cosa, the earliest Roman port known so far.

For more on the Sestius family and Koan wine, see Elizabeth Lyding Will, “The Roman Amphora: Learning from Storage Jars,” AO 03:01.

John P. Oleson’s study of this material indicates that it comes from North Africa as well as Italy; see Robert D. Ballard, Anna Marguerite McCann et al., “The discovery of ancient history in the deep sea using advanced deep submergence technology,” Deep-Sea Research I, vol. 47, no. 9 (2000), pp. 1612–1614.

See Cemal Pulak, “Shipwreck! Recovering 3,000-Year-Old Cargo,” AO 02:04.

Endnotes

McCann is mainly responsible for the material on Skerki Bank and Brody for the material on the Ashkelon and Black Sea wrecks. Artifacts from both the Skerki Bank and Ashkelon are now on exhibit at the Institute for Exploration at the Mystic Aquarium, in Mystic, Connecticut.

Jason has lent its name to the Jason Projects, which are dedicated to educating children in science and deepwater archaeology. The investigation at Skerki Bank in 1989 was the first Jason Project. Conceived and directed by Robert Ballard, it included the first interactive television directly from the sea floor.

The pine tar was analyzed by Curt W. Beck, Amber Research Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Vassar College.

The 1997 archaeology-conservation team headed by McCann included: J.P. Oleson, University of Victoria, British Columbia; J. Adams, University of Southampton; B. Foley, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; D. Piechota, Object and Textile Conservation, Arlington, Massachusetts; C. Giangrande, Institute of Archaeology at University College, London.

Anna Marguerite McCann and John P. Oleson will publish the material on the 1997 Skerki expedition in a forthcoming volume of the Journal of Roman Archaeology.

See McCann, “The Riace Bronzes: Gelon and Hieron of Syracuse?” in From the Parts to the Whole: I. Acta of the 13th International Bronze Conference, held at Cambridge, Massachusetts, from May 28 to June 1, 1996; see also C.C. Mattusch, A. Brauer and S.E. Knudsen, eds., Journal of Roman Archaeology supplemental series no. 39 (2000), pp. 97–105.