053

The combined expression “Jewish Christian,” made up of two seemingly contradictory concepts, must strike readers not specially trained in theology or religious history as an oxymoron. For how can someone simultaneously be a follower of both Moses and Jesus? Yet at the beginning of the Christian movement, in the first hundred years of the post-Jesus era, encounters with Jewish Christians (also called Judeo-Christians) distinguishable from gentile Christians were a daily occurrence both in the Holy Land and in the diaspora.

During his days of preaching, Jesus of Nazareth addressed only Jews, “the lost sheep of Israel” (Matthew 10:5; 15:24). His disciples were expressly instructed not to approach gentiles or Samaritans (Matthew 10:5). On the few occasions that Jesus ventured beyond the boundaries of his homeland, he never proclaimed his gospel to pagans, nor did his disciples do so during his lifetime. The mission of the 11 apostles to “all the nations” (Matthew 28:19) is a “post-Resurrection” idea. It appears to be of Pauline inspiration and is nowhere else found in the Gospels (apart from the spurious longer ending of Mark [Mark 16:15], which is missing from all the older manuscriptsa). Jesus’ own perspective was exclusively Jewish; he was concerned only with Jews.

We learn from the Acts of the Apostles that the primitive community of Jesus followers consisted 054 of 120 Jewish people, including the 11 apostles and the mother and brothers of Jesus (Acts 1:14–15). This is incidentally the last reference to Mary in the New Testament, although there are further allusions to the male siblings of Jesus in Acts and in Paul’s letters. James, “the brother of the Lord,” as Paul refers to him, is presented as the leader of the Jerusalem church (Acts 15:19; Galatians 1:19). According to another Pauline passage, the married brothers of Jesus also acted as missionaries of the gospel (1 Corinthians 9:5).

On the feast of Pentecost that followed the crucifixion, Peter and the rest of the apostles were metamorphosed under the influence of the divine Spirit from a group of gutless fugitives into born-again champions of faith in Jesus, the risen Messiah. Their charismatic proclamation to the Jerusalem crowds instantaneously increased the original nucleus of 120 Jesus followers by 3,000 new Jewish converts. All the converts were asked to do was to believe in Peter’s teaching about Jesus and to be baptized in his name.

The individual members of the Jerusalem Jesus party did not call themselves by any specific name, but their religious movement was known as “the Way” (Acts 9:2, 19:9, 24:14), short for “the Way of God.” Only at a later date, after the establishment of a community in Antioch in northern Syria, do we encounter in Acts 11:26 the specific designation Christianoi (“Christians” or Messianists), applied to the members of that particular church.

How did the original Judeo-Christians of Jerusalem compare to their Jewish neighbors? In some essential ways they did not differ from them at all. The Judeo-Christians considered themselves Jews, and their outward behavior and dietary customs were Jewish. In fact, they faithfully observed all the rules and regulations of the Mosaic Law. In particular, the apostles and their followers continued to frequent the religious center of Judaism, the Temple of Jerusalem, for private and public worship; it was there that they performed charismatic healings (Acts 3:1–10; 5:12, 20, 25, 42). According to Acts, the entire Jesus party assembled for prayer in the sanctuary every day (Acts 2:46). Even Paul, the chief opponent of the obligatory performance of Jewish customs in his churches, turned out to be a Temple-goer on his occasional visits to Jerusalem. He once fell into a trance in the course of his prayer in the House of God (Acts 22:17) and on a later occasion he underwent the prescribed purification rituals before commissioning the priests to offer sacrifice on his behalf (Acts 21:24–26).

In addition to their attachment to the Law of Moses, including worship in the Temple, the religious practice of the first Jewish Christians also included the “breaking of the bread” (Acts 2:46). This breaking of the bread was not a purely symbolic cultic act but a real meal. It had the double purpose of feeding the participants and symbolically uniting them with one another as well as 055 with their Master Jesus, and with God. The frequency of the rite is not immediately specified, but the initial impression is that it took place daily, not unlike the sacred dinner of the fully initiated Essenes described by the Jewish writers Philo and Josephus and by the Community Rule of the Dead Sea Scrolls. “And day by day, attending the Temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous heart” (Acts 2:46). On the other hand, according to Acts 20:7, Paul in Troas broke the bread on the first day of the week, and the Didache, the earliest Christian treatise (late first century C.E.), also orders that the bread should be broken and thanksgiving (Eucharist) performed each Sunday (Didache 14.1).

The Jerusalem Jewish Christians also practiced religious communism. “No one said that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had everything in common” (Acts 4:32). They were not formally obliged to divest themselves of their property and goods, as was the case with the Essenes at Qumran, but strong moral pressure was imposed; not to do so would have been judged improper.

So prior to the admission of gentile candidates, the affiliates of the Jesus party appeared to ordinary people in Jerusalem as representatives of a Jewish movement or sect. They were comparable to the Essenes in number and they exhibited similar customs such as the daily solemn meal and subsistence from a common kitty. Indeed, the followers of Jesus were referred to in the late 50s of the first century as the “sect [hairesis] of the Nazarenes” (Acts 24:5, 14). In later patristic literature the Judeo-Christians were designated as the Ebionites or “the Poor.” The church historian Eusebius (260–339 C.E.) reports that up to the Bar-Kokhba war (the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome [132–135 C.E.]) all of the 13 bishops of Jerusalem, starting with James, the brother of Jesus, came from the “circumcision” (Ecclesiastical History 4.3,5).

Acts identifies the demographic watershed regarding the composition of the Jesus movement. It began around 40 C.E. with the admission into the church of the family of the Roman centurion Cornelius in Caesarea (Acts 10). Later came the gentile members of the mixed Jewish-Greek church in Antioch (Acts 11:19–24; Galatians 2:11–14), as well as the many pagan converts of Paul in Syria, Asia Minor and Greece. With them the Jewish monopoly in the new movement came to an end. Jewish and gentile Christianity was born.

Let us look more closely at these events.

In the Cornelius episode (Acts 10) the Pentecost-like ecstasy of the Roman centurion and his entourage persuaded the astonished Peter to baptize them without further ado. This, however, seems to have been an exceptional event; no further conversion of a gentile is recorded in the Holy Land anywhere in the New Testament.

It was in the Syrian city of Antioch in the late 40s C.E. that the once-novel became frequent. Emigré members of the Jerusalem church were joined there by gentiles evangelized and baptized by Judeo-Christians originating from Cyprus and Cyrene (in North Africa). The mother church in Jerusalem dispatched Barnabas to run the new mixed community, and Barnabas hurried to Tarsus in Cilicia to persuade his friend Saul/Paul, already a believer in Christ, to join him in looking after the new church. The Jewish and the gentile Christians of Antioch coexisted happily and ate together. When visiting the community, Peter willingly participated in their common meals. However, when some extra-zealous representatives of the Jerusalem church headed by James the brother of Jesus arrived in Antioch, their disapproving attitude compelled all the Jewish Christians, including even Peter and Barnabas, but with the notable exception of Paul, to discontinue their table fellowship 056 with the brethren of Greek stock (Acts 11:2). As a result, union, fraternity and harmony in the new mixed church disappeared. The outraged Paul confronted Peter and publicly called him a hypocrite (Galatians 2:11–14), creating the first major row in Christendom.

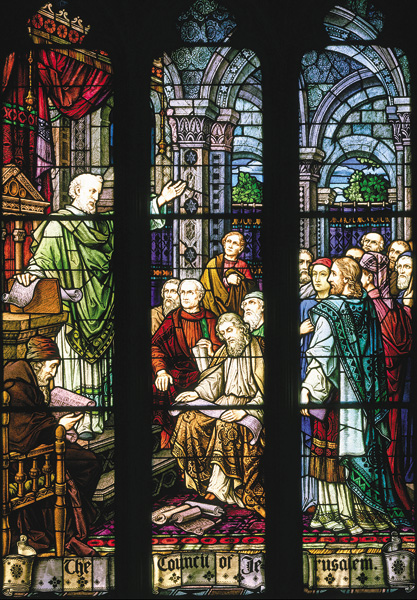

After Paul’s first successful missionary journey to Asia Minor, the entry of pagans into the Jesus fellowship became a particularly acute issue. A council of the apostles, attended by Paul and Barnabas, was convened in Jerusalem, at which James the brother of the Lord and head of the mother community overruled the demands of the extremist members of his congregation and proposed a compromise solution (Acts 15:19–21): Gentiles wishing to join the church would be exempted from the full rigor of the Law of Moses, including circumcision, 057 and would merely be required to abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from the consumption of blood, from eating non-ritually slaughtered meat, and from certain sex acts judged particularly odious by Jews.

These rules were necessarily intended for gentile converts in the diaspora. In Jerusalem different conditions prevailed, for gentile Christians could not join their Judeo-Christian coreligionists in the Temple as non-Jews were prohibited under threat of instant death to set foot in the area of the holy precinct reserved for Jews.

The Jerusalem council of the apostles marked the beginning of the separate development of Jewish and gentile Christianity. They both agreed on some essentials and ardently expected the impending second coming of Christ, the resurrection of the dead and the inauguration of the Kingdom of God. Paul himself insisted that it would happen in his own lifetime (1 Thessalonians 4:15–17). In other respects, however, they saw things differently. The original Judeo-Christian baptism (a rite of purification) and the breaking of the bread (a solemn communal meal) were transformed in the gentile church under the influence of Paul. Baptism developed into a mystical participation in the death, burial and resurrection of Jesus. The communal meal became a sacramental reiteration of the Last Supper. The perceived differences soon led to animosity and to an increasing anti-Jewish animus in the gentile church.

Two of the oldest Christian writings offer a splendid insight into the divergences between the two branches of the Jesus followers. The Didache, or Doctrine of the Twelve Apostles, probably composed in Palestine or Syria, is our last major Jewish-Christian document preserved in full. The Epistle of Barnabas is one of the earliest expressions of gentile Christianity, filled with anti-Jewish strictures.

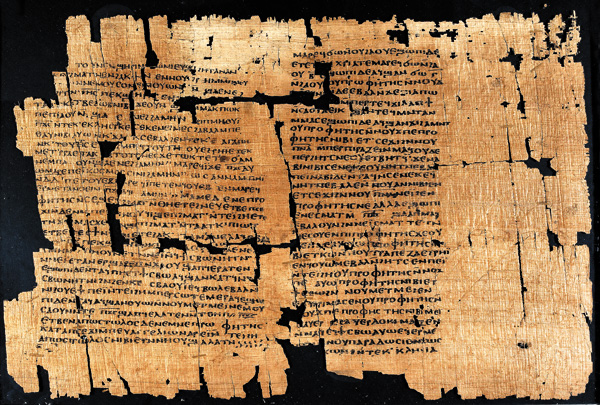

The Didache is generally assigned to the second half of the first century C.E., thus probably antedating some of the writings of the New Testament. Its religious program is essentially a summary of the Mosaic Law, the love of God and of the neighbor, to which is added the so-called “golden rule” in its negative Jewish form: “Whatever you do not want to happen to you, do not do to another” (Didache 1.2; cf. the positive Gospel version: “Whatever you wish that men would do to you, do so to them” [Matthew 7:12; Luke 6:31] ). The lifestyle recommended in the Didache is that of the primitive Jerusalem community described in Acts, including religious communism: “Share all things with your brother and do not say that anything is your own” (Didache 4.8). The Didache seems to recommend the observance of the entire Mosaic Law or at least as much of it as is possible (Didache 6.2).

Baptism is presented as an ablution, a purification rite; and a spray of water may be substituted for immersion if no pools or rivers are available. Communal prayer entailed the recitation of “Our Father” thrice daily. The thanksgiving meal (Eucharist) was celebrated on the Lord’s Day (Sunday) 058 (Didache 14:1). It was a real dinner as well as the symbol of spiritual food. No allusion is made in Pauline fashion to the Lord’s Supper.

Teaching authority in the Didache lay in the hands of itinerant prophets whom we know also from Acts 11:27–28. They were supplemented by bishops and deacons. However, these were not appointed by the successors of the apostles, as became the rule in the gentile churches, but democratically elected by the community.

Perhaps the most significant element of the Didache’s doctrine concerns its understanding of Jesus. This primitive Judeo-Christian writing contains none of the theological ideas of Paul about the redeeming Christ or of John’s divine Word or Logos. Jesus is never called the “Son of God.” Astonishingly, this expression is found only once in the Didache where it is the self-designation of the Antichrist, “the seducer of the world” (Didache 16.4). The only title assigned to Jesus in the Judeo-Christian Didache is the Greek term pais, which means either servant or child. However, as Jesus shares this designation in relation to God with King David (Didache 9.2; see also Acts 4:25), it is clear that it must be rendered as God’s “Servant.” If so, the Didache uses only the lowliest Christological qualification about Jesus.

In short, the Jesus of the Didache is essentially the great eschatological teacher, who is expected to reappear soon to gather together and transfer the dispersed members of his church to the Kingdom of God. The Pauline-Johannine ideas of atonement and redemption are nowhere visible in this earliest record of Judeo-Christian life. While handed down by Jewish teachers to Jewish listeners, the image of Jesus remained close to the earliest tradition underlying the Synoptic Gospels, and the Christian congregation of the Didache resembled the Jerusalem church portrayed in Acts.

The switch in the perception of Jesus from charismatic prophet to superhuman being coincided with a geographical and religious change, when the Christian preaching of the gospel moved from the Galilean-Judean Jewish culture to the pagan surroundings of the Greco-Roman world. At the same time, under the influence of Paul’s organizing genius, the church acquired a hierarchical structure governed by bishops with the assistance of presbyters and deacons. The disappearance of the Jewish input opened the way to a galloping “gentilization” and consequent de-judaization and anti-judaization of nascent Christianity, as may be detected from a glance at the Epistle of Barnabas, the earliest work of gentile Christianity.

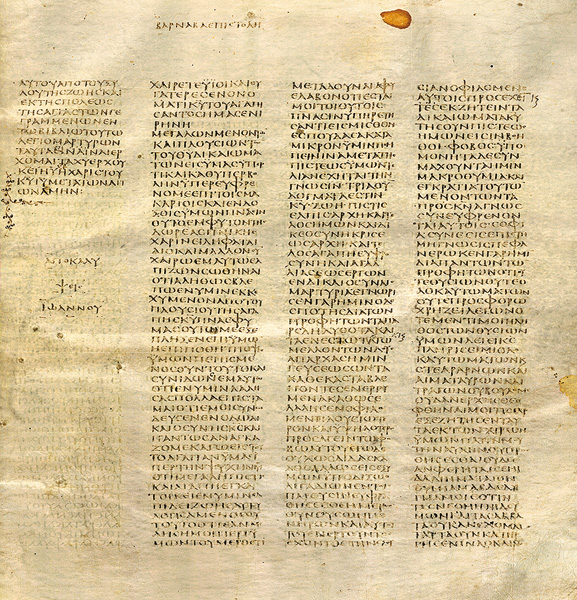

This letter—falsely attributed to Barnabas, the companion of Paul—is the work of a gentile-Christian author, probably from Alexandria. It was most likely written in the 120s C.E. and almost made its way into the sacred books. It is included in the oldest New Testament codex, the fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus but was finally declared non-canonical by the church. A reference to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem definitely dates it after 70 C.E., but the absence of any allusion to the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 C.E.) suggests that the epistle was written before c. 135. It is a hybrid work, in which moral instructions (Barnabas 18–21) based on a Jewish tractate on the way of light and the way of darkness, attested to also in the Didache 1–5, and ultimately in the first-century B.C.E. Community Rule among the Dead Sea Scrolls, is preceded by a lengthy anti-Jewish diatribe (Barnabas 1–17). The author depicts two quarreling parties designated simply as “we” and “they,” the first representing the Christians and the second the Jews, and the dispute is founded on the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint), which both factions consider their own property.

Barnabas aims to instruct his readers in “perfect knowledge” (gnosis) by revealing to them the true meaning of the essential Biblical notions of Covenant, Temple, sacrifice, circumcision, Sabbath and food laws. He insists that the Jews are mistaken in taking the institutions and precepts of the Old Testament in the literal sense; they are to be interpreted allegorically in conformity with 076 the exegesis in vogue in Alexandria. In fact, the laws of Moses have been spiritualized in the new law revealed by Jesus (Barnabas 2:5). Sacrifice should not amount to cultic slaughter but demand a broken heart, nor is forgiveness of sin obtained through the killing of animals but through the mystical sprinkling of the blood of Christ (Barnabas 5:1–6). The ideas of Paul, ignored by the author of the Didache, are in the forefront of Barnabas’s thought. According to him, those endowed with gnosis know that the grace of the true circumcision of the heart is dispensed not by the mutilation of the flesh but by means of the cross of Jesus (Barnabas 9:3–7).

For Barnabas and his gentile Christian followers, the covenant between God and the Jews was a sham; it was never ratified. When, bringing down the Law from Mt. Sinai, Moses saw that the Jews were engaged in the worship of the golden calf, he smashed into pieces the two stone tablets inscribed by God’s hand, and thus rendered the Jewish covenant null and void. It had to be replaced by the covenant sealed by the redemptive blood of “beloved Jesus” in the heart of the Christians (Barnabas 4:6–8, 14:1–7).

Barnabas’s portrait of Jesus is considerably more advanced than the Didache’s “Servant” of God. Barnabas calls Jesus “the Son” or “the Son of God” no fewer than a dozen times. This “Son of God” had existed since all eternity and was active before the creation of the world. It was to this preexistent Jesus that at the time of “the foundation of the world” God addressed the words, “Let us make man according to our image and likeness” (Barnabas 5:5, 6:12). The quasi-divine character of Jesus is implied when Barnabas explains that the Son of God took on a human body because without such a disguise no one would have been able to look at him and stay alive (Barnabas 5:9–10). The ultimate purpose of the descent of “the Lord of the entire world” among men was to enable himself to suffer “in order to destroy death and show that there is resurrection” (Barnabas 5:5–6). We are in, and perhaps slightly beyond, the Pauline-Johannine vision of 077 078 Christ and his work of salvation.

The parting of the ways between Jewish and gentile Christianity is manifest already at this stage, and the Epistle of Barnabas marks the start of the future doctrinal evolution of the church on exclusively gentile lines. Half a century after Barnabas, the bishop of Sardis, Melito, declared that the Jews are guilty of deicide: “God has been murdered … by the right hand of Israel” (Paschal Homily 96). Jewish Christianity makes no sense any longer.

The Didache is the last flowering of Judeo-Christianity. After Hadrian suppressed the Second Jewish Revolt in 135 C.E., the decline of Jewish Christianity began. Justin Martyr (executed in 165 C.E.) proudly notes that in his day non-Jews largely outnumbered the Jewish members of the church (First Apology).

Thereafter, Judeo-Christianity, the elder sister, adhering to the observance of the Mosaic precepts and combining them with a primitive type of faith in Jesus, progressively became a fringe phenomenon. Judeo-Christians progressively vanished, either rejoining the Jewish fold or being absorbed in the gentile church.

This article is adapted from Geza Vermes’s article “Jews, Christians and Judaeo-Christians” that appeared in the December 2011 issue of Standpoint, a political/cultural magazine published in London. Our thanks to editor Daniel Johnson.—Ed.

The combined expression “Jewish Christian,” made up of two seemingly contradictory concepts, must strike readers not specially trained in theology or religious history as an oxymoron. For how can someone simultaneously be a follower of both Moses and Jesus? Yet at the beginning of the Christian movement, in the first hundred years of the post-Jesus era, encounters with Jewish Christians (also called Judeo-Christians) distinguishable from gentile Christians were a daily occurrence both in the Holy Land and in the diaspora. During his days of preaching, Jesus of Nazareth addressed only Jews, “the lost sheep of Israel” (Matthew 10:5; 15:24). […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “How the New Testament Gospels Developed,” sidebar to Helmut Koester, “Was Morton Smith a Great Thespian and I a Complete Fool?” in “ ‘Secret Mark’: A Modern Forgery?” BAR 35:06.