Jerusalem was under siege.

The Babylonian army, led by King Nebuchadnezzar, was at the city gates. The prophet Jeremiah proclaimed to the citizens of Jerusalem that it was futile to resist because YHWH had raised up the Babylonian king to judge Judah. Jerusalem, Jeremiah warned, should surrender.

Jeremiah’s words were extremely unpopular with the Hebrew officials defending Jerusalem. “Let that man be put to death,” they told the Judahite king Zedekiah, “for he [Jeremiah] disheartens the soldiers, and all the people who are left in this city, by speaking such things to them. That man is not seeking the welfare of the people, but their harm!” (Jeremiah 38:4).

King Zedekiah acquiesced: “He is in your hands; the king cannot oppose you in anything!”

“So they took Jeremiah,” the Bible continues, “and put him down in the pit of Malchiah, the king’s son, which was in the prison compound; they let Jeremiah down by ropes. There was no water in the pit, only mud, and Jeremiah sunk into the mud” (Jeremiah 38:6).

The king’s men left Jeremiah to die. The entire nation had apparently rejected Jeremiah and his message: No one from Judah interceded for him. If not for the intervention of an obscure biblical figure, a black foreigner called Ebedmelech the Cushite, Jeremiah probably would not have lived to see his prophecies come true.

Ebedmelech, whose Hebrew name means “servant of the king,” interceded on Jeremiah’s behalf, securing permission from King Zedekiah to rescue the prophet from the muddy cistern. Ebedmelech pleaded, “O lord king, these men have acted wickedly in all they did to the prophet Jeremiah; they have put him down in the pit to die there of hunger” (Jeremiah 38:9). The king instructed Ebedmelech the Cushite: “Take with you thirty men from here, and pull the prophet Jeremiah up from the pit before he dies” (Jeremiah 38:10); and he did.

In recent years, the field of Hebrew Bible Studies has been flooded with monographs, articles and books dealing with women in the Bible. It seems that every female character has been analyzed and reanalyzed dozens of times.a This productive study of “marginalized” figures has challenged those of us who tend to plod along traditional lines to look at the text from a different perspective.

Surprisingly, this interest in marginalized figures has not carried over to other peoples, particularly blacks. Numerous black figures come and go across the pages of Scripture, yet they have inspired little discussion among Bible scholars.

Ebedmelech is such a figure. Although the Bible’s description of Ebedmelech is limited, by examining the historical accounts of the Cushites we can begin to understand who Ebedmelech was, what he was doing in Jerusalem during the siege and why he alone came to Jeremiah’s rescue.

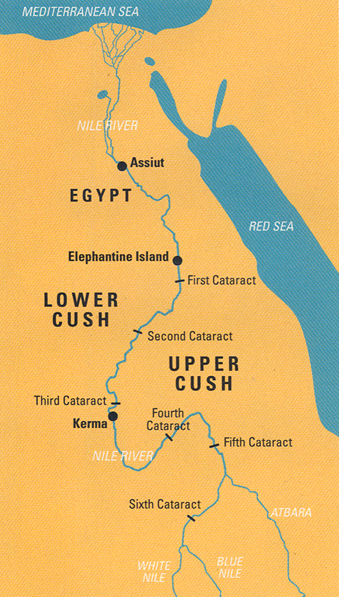

The nation of Cush stretched along the Nile south of Egypt, upstream from the cataracts. Historians refer to this region by various terms—Nubia, Ta-sety, Wawat, Cush, Meroe, Ethiopia. But the ethnicity of the region was clearly black African (the evidence from Egyptian art is overwhelming1), and although the names of the region varied, the political and ethnic identity of the area remained steady from 2500 B.C.E. to 400 C.E.2

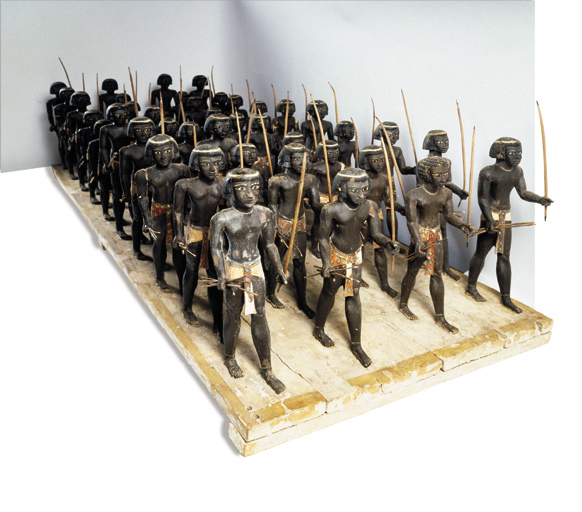

The Cushites appear frequently in the literature and art of the ancient Near East, where they had a reputation as soldiers. Because of Cush’s close proximity to Egypt, Cushites appear most frequently in Egyptian literature. The Egyptians often called the region Ta-sety, meaning “Land of the Bow,” probably a reference to the weapon most closely associated with Cush.3 Excavation of a tomb (c. 2500–2052 B.C.E.) in Kerma, the early Cushite capital, revealed a young archer lying on his side with his bow and bowstring in his hand.4 Also, models of 40 Cushite soldiers, all archers carrying bows, were discovered in the tomb of Mesehty at Assiut, in Egypt, from about the same period (c. 2040 B.C.E.).5 These Cushite archers have been described as the pharaoh’s elite bodyguards.6

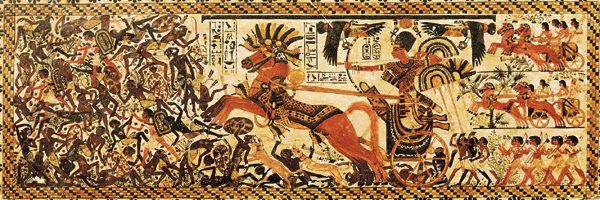

Cushite mercenaries served in the Egyptian army as early as Dynasty VI (c. 2400–2250 B.C.E.), when they participated in raids on the Asiatics.7 Throughout most of the second millennium B.C.E., Cush was under Egyptian control and Cushite soldiers were regularly incorporated into the Egyptian army. The Amarna Letters—a collection of Egyptian diplomatic correspondence from the 14th century B.C.E.—mention Cushite troops serving in Egyptian garrisons in Canaan.8

The Cushites, however, were not always complacent subjects. Although some joined their Egyptian neighbors in battle, others fought against them. Egyptian historical documents record dozens of campaigns into Cush. In addition, even when they were part of the Egyptian army, the Cushite auxiliaries occasionally acted independently. In the Amarna Letters, for example, the Egyptian prince stationed in Jerusalem, ‘Abdi-

According to the Bible, which includes 54 references to Cush and the Cushites, Cushite soldiers also served in the Israelite army. After Absalom’s revolt was defeated, Joab chose “a Cushite” to take the news of Absalom’s death to his father David (2 Samuel 18:19–33).10 This casual reference to a Cushite in David’s army seems to indicate that the presence of Cushite troops was not at all unusual.

Another biblical reference, however, describes a Cushite soldier fighting against Israel: Second Chronicles 14:9–15 recounts a battle between Zerah the Cushite and Judah during the reign of Asa (913–873 B.C.E.). Zerah attacked with a vast army (literally “a thousand thousands”), including 300 chariots. Asa called to YHWH for assistance: “Help us, O Lord our God, for we rely on You, and in your name we have come against this great multitude” (2 Chronicles 14:10).11 Zerah the Cushite was most likely a Cushite general from south of Egypt, either working directly for the pharaoh Osorkon I (924–889 B.C.E.) or invading under a treaty provision with him.

In the eighth century B.C.E., the Cushite kingdom became increasingly powerful. In 720 B.C.E. the Cushite king Piye (sometimes called Pi-ankhi) conquered Egypt and established the XXVth Dynasty, which ruled over Egypt for nearly 50 years. Moreover, Cush apparently established military and economic ties with the Assyrians, the other great Near Eastern superpower at this time. A group of Assyrian cuneiform texts, called the Horse Lists, describes the Assyrian cavalry horses as mesaya, meaning “from Mesu,” a region bordering Urartu that was famous for its cavalry; the Assyrian chariot horses, however, are called kusaya, or “from Cush.” Indeed, the Assyrian monarch Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 B.C.E.) opened a trade station in Egypt, evidently for the primary purpose of acquiring Cushite horses for his chariots.12 As horses became an increasingly critical component in war technology during the ninth and eighth centuries, chariot horses imported from Cush via Egypt became popular throughout the Levant.13

Individual Cushites are also often called Kusaya in the Wine Lists of Tiglath-Pileser III. One text records that a man called Kusaya delivered 20 bales of straw and 15 homers (about 10 bushels) of barley, presumably for horses. Kusaya and the other Cushite administrators mentioned in the Wine Lists may have served as equestrian experts, responsible for the Assyrian army’s horses. This practice continued into the reign of Ashurbanipal (668–627 B.C.E.).14

Assyrian art indicates that Cushite soldiers also lent their services to the enemies of Assyria. Reliefs on the palace walls at Khorsabad, belonging to the Assyrian ruler Sargon, depict foreign foot soldiers fighting against the Assyrian army during Sargon’s campaign against Palestine in 720 B.C.E. Pauline Albenda has noted that one of these soldiers, with “a beardless face, broad blunt nose, and small tight curls covering the head,” looks remarkably like the Cushites depicted in Egyptian art.15 Likewise, Assyrian reliefs from Nineveh portraying Sennacherib’s siege of the Judahite fortress at Lachish, south of Jerusalem, depict captured enemy soldiers that appear to be Cushites.16

By the seventh century B.C.E., Assyrian-Cushite relations had degenerated into open war. Tirhakah, a major military figure in Cushite and biblical history, reigned over Cush and Egypt from 690–664 B.C.E., during the XXVth Dynasty. According to 2 Kings 19:9 he marched out to fight against Sennacherib during the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem.

Sennacherib’s annals do not mention Tirhakah by name, as later Assyrian annals do, but they do mention this event. According to Sennacherib’s account, the Judahite king Hezekiah appealed to Egypt and Cush (both under Cushite rule) for help against the Assyrian siege, and the Cushite king responded by sending his army.17 Sennacherib apparently turned from his siege of Jerusalem to defeat this Egyptian-Cushite relief expedition and then returned to his siege, which proved unsuccessful. The Bible stresses that YHWH alone was responsible for the deliverance of Hezekiah and Jerusalem. For our purposes, however, it is significant to note that Judah was allied with a black king and a black nation against the Assyrians.

In 663 B.C.E. a family from Lower Egypt regained control of Egypt, with the aid of Greek and other mercenaries, and began strengthening Egypt’s southern frontier against the Cushites. Under Psammetichus, however, a large contingent of Egyptian troops defending the southern border defected to Cush, settling among the Cushites and intermarrying with them. Perhaps they were unhappy with the preference given to mercenary troops of other nationalities.18 Egypt then settled Jewish mercenary soldiers at the isle of Elephantineb on the Nile, as a frontier garrison against the Cushites.19 This settlement no doubt provided a point of contact between Jew and Cushite. Indeed, the name Cushi, “the Cushite,” is mentioned in the hoard of Aramaic papyri belonging to the ancient Jewish community on Elephantine.20

During the Persian period, King Cambyses (529–522 B.C.E.) conquered Egypt and prepared to invade Cush. The fifth-century B.C.E. Greek traveler and historian Herodotus provides a fascinating account of an envoy sent with gifts by the Persian king to the Cushite king to spy out the situation. The Cushite king rejected the gifts and defied Cambyses. He handed the Persian envoy a Cushite bow and stated that when Cambyses came back with an entire army strong enough to draw that bow, the Cushites might respect them. According to Herodotus, Cambyses then tried to invade Cush, but the expedition ended in total disaster.21 The Persians, however, did gain control of Egypt all the way up the Nile (that is, to the south) to Elephantine, which bordered on Cush. Once again, Herodotus tells us, the Cushites served as mercenaries. Clad in leopard and lion skins and armed with extremely long bows, Herodotus recounts, some Cushites served in the army of the Persian king Xerxes (485–465 B.C.E.).22

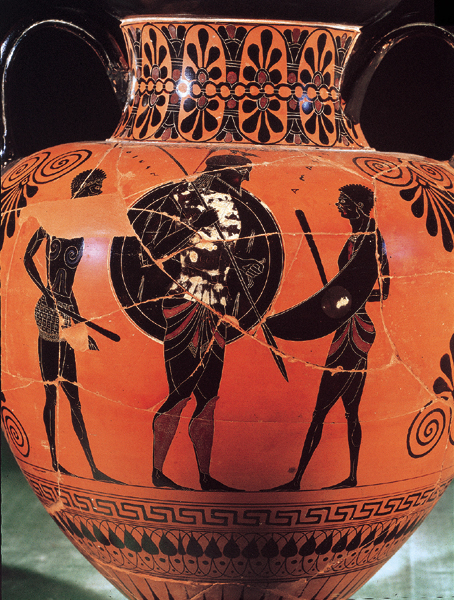

The Greeks, too, came to know Cushite soldiers, although the Greek writers referred to the region of Cush as “Ethiopia” (as do some modern English Bible translations). The black soldiers who appear numerous times in sixth- and fifth-century B.C.E. Greek art are probably Cushite mercenaries serving throughout the Greek world.23 Negroid stone figures found on Cyprus from the time of the Egyptian occupation (568–525 B.C.E.) may indicate that Cushite troops were also used in the Egyptian invasion and administration of Cyprus. The blacks depicted in a Minoan fresco suggest that Cushites may have come to Crete as auxiliaries as early as the mid-second millennium B.C.E.

Cushites also served in the army of the Carthaginian Hannibal in the late third century B.C.E. His famous war elephants probably came from Cush as well. War elephants are depicted on several Cushite reliefs, especially at Meroe, on the eastern bank of the Nile in Cush.24

Clearly, the Cushites were widely known throughout the ancient world as mercenaries, fighting for both sides in Egypt, Assyria, Israel, Persia and Greece.

With this historical background, let us return to Ebedmelech and the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, which lasted from about 588 to 586 B.C.E. The biblical text stresses Ebedmelech’s nationality, referring to him as “the Cushite” four times (Jeremiah 38:7, 10, 12, 39:16). To the inhabitants of Jerusalem, the term “Cushite” would have elicited images of black Africans. In Jeremiah 13:23 the prophet asks rhetorically, “Can the Cushite change his skin or the leopard his spots?” The point of Jeremiah’s question was that some things in life—such as the sinful behavior of Judah—had become as entrenched and unchangeable as skin color. For us, these words indicate that Cushites were so well known in Jeremiah’s Jerusalem that popular proverbs arose about their dark skin color.25 Perhaps Ebedmelech was part of a larger Cushite contingent stationed in Jerusalem. If so, their unique dress and skin color would probably have generated great interest on the part of the Jerusalemites.

It has been suggested that Ebedmelech may have received his Hebrew name, meaning “servant of the king,” because no one in Jerusalem could pronounce his Cushite name.26 The name does not mean that Ebedmelech was a servant or slave of Zedekiah, however. The title “servant of the king,” found on at least 11 seals and bullaec from ancient Judah, designated a high-ranking official or minister.27 The title implies submission to the ruler: Thus Moses, Joshua and David, the greatest leaders of Israel, are frequently called “servants” of YHWH.28 In Egyptian literature—and Cushite culture was integrally related to Egyptian culture—high government officials frequently refer to themselves as servants of the king or pharaoh.

Ebedmelech is also identified as a

In the Book of Jeremiah, the term

Ebedmelech’s bold public confrontation of Zedekiah, followed by Zedekiah’s compliance, indicates that he had considerable political clout. He may even have accused Zedekiah himself of wrongdoing.32 The most plausible explanation is that Ebedmelech was a high-ranking military officer—perhaps a leader of a contingent of royal bodyguards or Cushite soldiers. Cush at this time was closely bound, both culturally and militarily, to Egypt, and Egypt was the major military ally of Judah in Zedekiah’s rebellion against Babylonia. Ebedmelech may well have been a mercenary in the Egyptian army or, perhaps, the ranking representative of the Cushite-Egyptian army in Jerusalem, the equivalent of a modern-day military attaché. This would explain why he could easily obtain an audience with Zedekiah and why Zedekiah acquiesced so quickly: With Nebuchadnezzar’s powerful army at the gates of Jerusalem, Zedekiah could not risk offending the Egyptians and the Cushites, the only allies he had who could offer tangible military help.

It is significant that a foreigner acted to save the prophet of YHWH.33 While the entire nation of Judah was disobedient to YHWH, it was a black Cushite who confronted the king and delivered Jeremiah. The repetition of Ebedmelech’s Cushite nationality may be stressing the irony of his foreignness. Who could be more unlikely to deliver the prophet and to trust in YHWH than this black Cushite, this “Gentile of Gentiles?”

Jeremiah 39:15–18 adds an important postscript. In this passage, YHWH speaks to Jeremiah, promising him that Ebedmelech will survive even though Jerusalem will fall to the Babylonians. YHWH instructs Jeremiah: “Go and say to Ebedmelech the Cushite: ‘Thus said the Lord of Hosts, the God of Israel: I am going to fulfill My words concerning this city—for disaster, not for good—and they shall come true on that day in your presence. But I will save you [Ebedmelech] on that day—declares the Lord; you shall not be delivered into the hands of the men you dread. I will rescue you, and you shall not fall by the sword. You shall escape with your life, because you trusted Me—declares the Lord.’” When the entire Hebrew nation was being condemned because of disobedience and covenant violation, a black Cushite was delivered because of his faith—because he “trusted” in YHWH. YHWH did for Ebedmelech exactly what he would not do for Zedekiah—save him from the Babylonians. “Trust, as evidenced by Ebedmelech,” Hebrew Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann writes, “is a limit and alternative to Babylonian power and devastation.” Ebedmelech thus becomes the representative of an important remnant—the remnant of faith. The destruction of Jerusalem by YHWH is not “morally indifferent or undifferentiated.” Acts of faith and trust are salvific. Ebedmelech represents such action.34

Unlike Zedekiah and the Hebrew princes in Jerusalem who perished because they opposed Jeremiah and his message from YHWH, Ebedmelech was saved because he trusted in YHWH and defended Jeremiah. Ebedmelech, a foreign black soldier, represents the people of faith. For Christians, he foreshadows the future Gentile inclusion; an inclusion of both blacks and whites, based not on nationality or ethnicity, but on faith.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See, for example, the following BR articles: Tikva Frymer-Kensky, “Forgotten Heroines of the Exodus,” BR 13:06; Adrien Bledstein, “Was Eve Cursed? (Or Did a Woman Write Genesis?),” BR 09:01; Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “Prisca and Aquila—Traveling Tentmakers and Church Builders,” BR 08:06; Carey A. Moore, “Susanna—Sexual Harassment in Ancient Babylon,” BR 08:03; and Jane Schaberg, “How Mary Magdalene Became a Whore,” BR 08:05.

See Bezalel Porten, “Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine?” BAR 21:03.

Papyrus scrolls were commonly tied with string, and a lump of clay was placed over the knot. The sender then pressed a seal—bearing his name, his title and sometimes his father’s name—into the clay (called a bulla once it was stamped), making the document official. See the following articles in Biblical Archaeology Review: André Lemaire, “Royal Signature: Name of Israel’s Last King Surfaces in a Private Collection,” BAR 21:06; Hershel Shanks, “Jeremiah’s Scribe and Confidant Speaks from a Hoard of Clay Bullae,” BAR 13:05 and “In Private Hands,” BAR 22:02.

Endnotes

See Ladislas Bugner, ed., The Image of the Black in Western Art, vol. 1, From the Pharaohs to the Fall of the Roman Empire (New York: William Morrow, 1976). Note especially Jean Vercoutter, “The Iconography of the Black in Ancient Egypt: From the Beginnings to the Twenty-fifth Dynasty”; Jean Leclant, “Kushites and Meroïtes: Iconography of the African Rulers in Ancient Upper Egypt”; and Frank M. Snowden, “Iconographic Evidence on the Black Populations in Greco-Roman Antiquity.”

J. Daniel Hays, “The Cushites: A Black Nation in Ancient History,” Bibliotheca Sacra 153 (July–September 1996), pp. 270–280.

John H. Taylor, Egypt and Nubia, British Museum (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1991), p. 5. It is also possible, however, that the name “Land of the Bow” refers to the shape of the land. The Nile River is relatively straight in its course through Egypt. In Cush, however, due to the cataracts, the Nile makes a dramatic 180 degree bend, resembling the shape of a bow.

Eugen Strouhal, Life of the Ancient Egyptians (Norman, Oklahoma: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992), p. 203.

John A. Wilson, The Culture of Ancient Egypt (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1951), pp. 136, 138.

James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), 3rd ed. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 488. The translated term for the troops is “Nubian,” but William F. Albright explains in ANET that these troops should be identified with Cush.

Joab was reluctant to give the job to Ahimaaz, an Israelite. Perhaps Joab was worried about David’s response to the death of his son and decided that it would be more appropriate for a foreigner to deliver the news than an Israelite. See Charles Convoy, “Absalom! Narrative and Language in 2 Samuel 13–20, ” Analecta Biblica 81 (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1978), p. 69. Convoy suggests that Joab chose the Cushite, not necessarily because he was black, but simply because he was a foreigner.

Because this episode is not recorded in 2 Kings, several scholars doubt its historicity. Ernst Axel Knauf, for example, argues that Zerah could not have been a ruler from Cush, although he cites no evidence for this. He adds that Zerah also could not have been an Egyptian because Egyptians do not have names starting with “z.” He suggests that the story may refer to a later skirmish with Bedouins, especially since the text mentions camels. See Knauf, s.v. “Zerah,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary (ABD) (New York: Doubleday, 1992), vol. 6, pp. 1080–1081.

Knauf overlooks the fact that Zerah is a Cushite not an Egyptian. The Cushitic language is still not clearly understood, and it is doubtful whether one could state that Cushite names cannot start with a “z” sound.

Pierre Montet states that this invasion was by a Cushite army, but probably done with the pharaoh’s permission, perhaps as part of a treaty. See Montet, Egypt and the Bible, trans. Leslie R. Keylak (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1968), p. 43. Jacob M. Myers and John Bright state that Zerah was either a Cushite mercenary in the Egyptian army or, perhaps, an Arab. Their evidence for the Arab possibility, Habbakuk 3:7 and Numbers 12:1, is questionable, however, in regard to establishing an Arab connection to the term “Cush.” See Myers, II Chronicles, The Anchor Bible Series (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1965), p. 85, and John Bright, A History of Israel, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1981), pp. 234–235. The term “Cush” in the Hebrew Bible consistently refers to the area south of Egypt. Habakkuk 3:7 mentions “Cushan” in parallel with Midian, but this one reference to an enigmatic place called “Cushan” hardly justifies the identification of “Cush” as Midian.

The argument that Zerah is an Arab (or Bedouin) is weak. The context includes Egyptians (Shishak in 2 Chronicles 12), which further cements the identification of Cush. The Bedouin or Arab argument is further weakened by the mention of chariots in 2 Chronicles 14:9 and 16:8. The army of Zerah did not come on camels like Arabs, but rather on chariots, like Egyptians. Nowhere in the Hebrew Bible are chariots associated with Arabs, Bedouins, Midianites, or any other Arabian peninsula people. Nomadic peoples did not construct chariots. See Mary Aiken Littauer and J.H. Crouwel, s.v. “Chariots,” in ABD, vol. 1, p. 891.

Stephanie Dalley, “Foreign Chariotry and Cavalry in the Armies of Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II,” Iraq 47 (1985), pp. 46–47.

Dalley, “Foreign Chariotry,” pp. 31, 43–44. The texts are published as nos. 99–118 in vol. 3 of the series Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud, ed. Dalley and J.N. Postgate.

Dalley, “Foreign Chariotry,” p. 46. Cushites appear in the various lists four times. See J.V. Kinnier Wilson, The Nimrud Wine Lists (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1972), p. 93. Pauline Albenda also argues that Cushites were living in Nimrud during the eighth century B.C.E. See Pauline Albenda, “Observations on Egyptians in Assyrian Art,” Bulletin of the Egyptian Seminar 4 (1982), p. 8.

Albenda, “Egyptians in Assyrian Art,” p. 8. See also J.E. Reade, (“Sargon’s Campaigns of 720, 716, and 715 B.C.: Evidence from the Sculptures,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35 [1976], p. 100), who writes, “The heads of the enemies in battle (K), at least one of those in siege (J), and possibly those in Gabbutunu, are negroid; both Botta and Flandin were positive about this, though Layard saw the slabs later and tentatively questioned their conclusion; we must accept the original excavators’ opinion, and therefore identify these enemies as Egyptians or Nubians.”

Pritchard, ANET, pp. 287–288. The term used for Cush is Meluhha. At this time in Assyrian history this term was used to refer to Cush. See A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, rev. ed. (Chicago: The Univ. of Chicago Press, 1977), pp. 64, 408.

R.H. Hall, “The Restoration of Egypt,” The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., vol. 3, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988), pp. 293–294.

Ronald J. Williams, “The Egyptians,” in Peoples of Old Testament Times, ed. D.J. Wiseman (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), pp. 95–96. See also the Letter of Aristeas 13; and Herodotus, History 2.161.

Bezalel Porten and Ada Yardeni, “Literature, Accounts, Lists” in Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, vol. 3 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1993), p. 280.

Herodotus, History 3.152–153. In an inscription the Cushite king Nastesenen speaks of defeating k-m-b-s-u-d-n. Hall (“Restoration of Egypt,” pp. 312–313), argues that this is a reference to Cambyses. George Reisner, however (Harvard African Studies 2, 1923), rejects this connection, maintaining that Nastesenen was much later than Cambyses. See G. Buchanan Gray, “The Foundation and Extension of the Persian Empire,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 4, pp. 20–21.

Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1970), plates 17–22.

Note also that Zephaniah, a contemporary of Jeremiah, mentions Cush or Cushite three times in his three short chapters. Ronald E. Clements, Jeremiah, Interpretation (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1988), pp. 86–87.

Robert Deutsch and Michael Heltzer, Forty New Ancient West Semitic Inscriptions (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1994), p. 41.

Although in the Masoretic text (the standard Hebrew text of the Bible) Ebedmelech says, “these men have done wrong,” in the Septuagint (a Greek translation from the Hebrew) he tells Zedekiah, “you have done wrong.” In the Book of Jeremiah, the Septuagint is arguably the superior text.

Gordon H. Johnson, s.v. “

J.A. Thompson cites instances where

Johannes Schneider, s.v. “

Ziony Zevit, citing Greenfield in support, argues that ebed in Jeremiah should be translated as “vassal.” Zevit notes an Ugaritic letter (UT 2062) from the king to an official named Yadan, who is referred to as ‘bd.mlk (ebedmelech). See Zevit, “The Use of