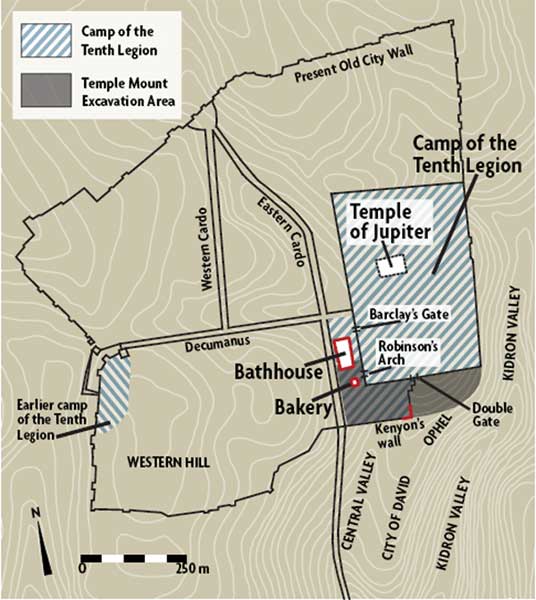

After the Romans destroyed the Temple and burned Jerusalem in 70 C.E., the Xth Legion (Fretensis) of the Roman army camped on the southwestern hill of the city, in the area known today as the Citadel, by Jaffa Gate.1 This was not, however, enough to stifle the resurgence of Jewish nationalism. In 132 C.E. what is known as the Second Jewish Revolt (the so-called Bar-Kochba Revolt) erupted, only to be suppressed, like the First Jewish Revolt, by the Roman army, this time led by the Emperor Hadrian. But it took him three years and many men. At its end, Hadrian ordered the city razed. Jews were forbidden to enter the city except once a year to mourn the destruction of their temple. In the report of his victory to the Roman Senate, however, Hadrian omitted the customary salutation: “I and the army are well.”

On the old Jewish city of Jerusalem, Hadrian erected a new Roman city that he named Aelia Capitolina. Aelia was his own name—Publius Aelia Hadrianus. Capitolina refers to the three Capitoline gods—Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. Hadrian also changed the name of the country from Judaea to Palaestina in an effort to eradicate any connection with the Jews.

Whether the beginning of the construction of Aelia Capitolina was a cause of the Jewish revolt or, instead, it was established only after the revolt was suppressed, is a question on which scholars disagree. It is my contention here that, in connection with the building of the Roman city, Hadrian moved the camp of the Xth Legion from the southwestern hill of Jerusalem to the Temple Mount itself, which could no longer be left abandoned considering its strategic importance. Only by asserting control of the focal point of Jerusalem could Hadrian be assured of long-term control of the city.

My evidence comes principally from the excavations of my grandfather, Benjamin Mazar, between 1968 and 1978 at the foot of the southern and western walls of the Temple Mount. Professor Mazar died in 1995 without completing his final report, and I have been charged by an academic committee with completing it.2

Of course, the best archaeological evidence for my contention regarding the encampment of the Xth Legion would likely be found on the Temple Mount. It is not possible, however, to conduct archaeological excavations there because of objections by the Waqf, the Muslim religious trust that controls the area. Moreover, the Xth Legion’s structures on the Temple Mount have surely been destroyed during the considerable building that has taken place over the generations. Nevertheless, traces would be distinguishable in the archaeological strata that have since accumulated, much like the buildings uncovered in Benjamin Mazar’s excavations south and southwest of the Temple Mount.

Many indications of the presence of Roman soldiers—and more specifically of the Xth Legion—were found in these excavations. For example, over 190 Aelia Capitolina coins were uncovered. In contrast, on the southwestern hill where the Xth Legion was billeted after the First Jewish Revolt, only six such coins were excavated. This rather clearly indicates that the legion had moved by the time Aelia Capitolina was established and that the Roman soldiers were active in the area at the foot of the Temple Mount.3

Another find that contributes to this view is an outstanding bronze figurine of a soldier from an auxiliary force of the Roman army. In addition, a number of gemstones bear depictions common in this military context—Mars, the god of war; an eagle, symbol of the Xth Legion; and an armed horseman, probably connected with the Roman army’s auxiliary forces. These gemstones were likely owned by Roman soldiers.4 The many game dice from the Roman period found in the excavations were probably used by the soldiers as well.

I believe that the Xth Legion’s camp at this time included both the Temple Mount and the area at the foot of its southwestern corner. The latter area would have been contained within a wall adjoining the Temple Mount enclosure walls, and in this way the entire camp—both on the Temple Mount and the area below it—would have fortified a single cohesive unit. This wall would have been especially important because there was no city wall of Aelia Capitolina.

A portion of this Xth Legion enclosure wall below the Temple Mount can perhaps still be located. About 600 feet south of the southeast corner of the Temple Mount, a wall descends south for about 300 feet, then turns 90 degrees to the west. In 1964 British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon excavated an area (her Area J) adjacent to the western side of this corner of the wall.5 She concluded that this wall was originally built during the period of Aelia Capitolina.6 In 1966 she excavated along the eastern side of the same corner (her Area SI),7 the results of which confirmed her dating of the wall. Although she misidentified it as a city wall of Aelia Capitolina, it is very likely a wall enclosing the Roman camp.8

The annexation of this area below the Temple Mount to the Xth Legion camp on the Temple Mount had the strategic advantage of preventing the detachment of the Temple Mount from its environs. The two sections of the camp—on top of the Temple Mount and at the foot of its southwestern corner—functioned as one unit. Direct passage between the two was probably through the Double Gate on the southern Temple Mount wall, Barclay’s Gate on the western wall and the massive breach (nearly 200 feet long) in the western third of the southern wall made when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

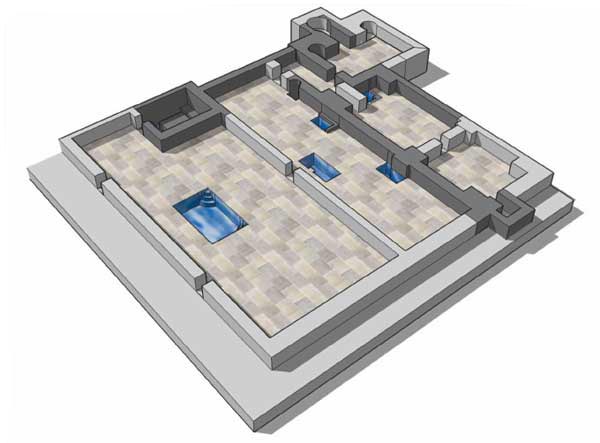

In the area below the Temple Mount, Benjamin Mazar found structures that are entirely consistent with this interpretation. Most impressive are the remains of a large Roman bathhouse that covers approximately 20,000 square feet. In places, the bathhouse walls survived to a height of over 6 feet; in other places only the underground elements remain. The original construction of the bathhouse rests on debris from the Roman destruction of 70 C.E. (the bathhouse must be later than the stratum below it), and it apparently continued in use until the Arab period in the seventh century C.E.

What is especially interesting—and telling—about the bathhouse is its plan: It is a “row type” of bathhouse. That is, the plan follows a programmed bathing course from the cold area to the tepid, then to the hot rooms and back.

Two elements of the bathhouse are of special interest: (1) the positioning of the three pools in the frigidarium (cold room) and (2) the sodatorium (sweat room), which is round within a square encasing wall and was located in a kind of extension of the building. The architecture of this bathhouse tells us about its date and context. Three pools in the frigidarium appear in Roman bathhouses no earlier than the second century C.E. The plan of the sodatorium and its location on the margins of the main part of the building are characteristic of urban bathhouses in Italy and Mediterranean provinces up to the end of the first century C.E. However, these characteristics continue to be found into the second century C.E. in military bathhouses (and in the distant northern provinces). In the heart of the Roman empire, change occurred more quickly than in the provinces of the Roman east. In short, the structure’s plan suggests it was a military bathhouse from the second century C.E.9

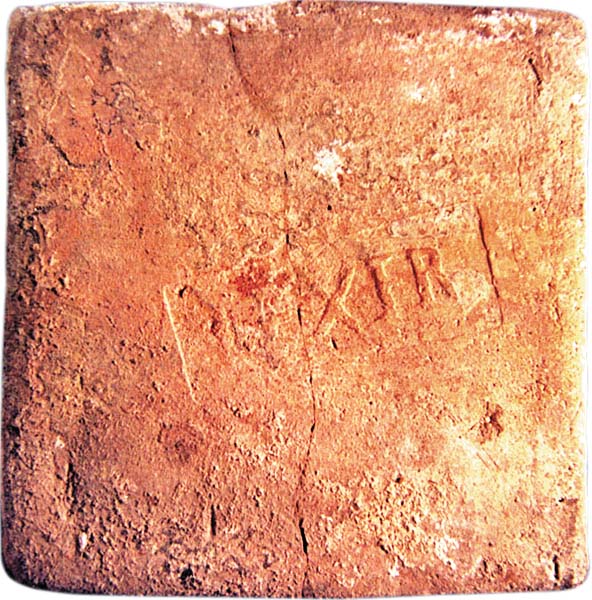

In the tepidaria (warm rooms) and caldaria (hot rooms) the little squares on the plan represent hypocaust pillars, brick supports for the raised floor that allowed hot steam to be funneled into these rooms. These, too, add evidence to the thesis of this article: Many of the bricks of the hypocaust floor are impressed with the Xth Legion stamp.

On the basis of all this evidence, I believe that the bathhouse was constructed in the second century C.E. as a military bathhouse for the Xth Legion and continued in use, with various alterations, to the end of the Byzantine period.

Another building located west of the Temple Mount at the extreme southern end was integrated into the remains of the destroyed vaults of the massive staircase structure that led over Robinson’s Arch to the entrance to the Royal Stoa on the Temple Mount of the Second Temple period. This building was a bakery. The bakery, which can also be dated to the period of Aelia Capitolina, contains several round ovens sunk into the floor. The ovens are paved with broken bricks, a number of which bear—again—the stamp of the Xth Legion. In one of the bakery rooms, a stamp with the Latin inscription PRIM (primus) was found, which was used as a stamp to indicate a product, in this case bread, of the highest quality.

The Xth Legion stamp impressions are of special interest because in many cases impressions from the first, second and third centuries can be distinguished from one another. Overall, more than 240 of these impressions were found in the excavation at the foot of the Temple Mount. Only very few are of the first or third century, and all of those found in the bathhouse and bakery are from the second century.10 In contrast, in the area of the Citadel on the southwestern hill, where the Xth Legion encamped before the establishment of Aelia Capitolina, only one such impression was found in situ. This provides further evidence for the argument that Roman construction on the southwestern hill should be associated with the first phase of the Xth Legion’s stay in Jerusalem (70–130 C.E.). Roman construction at the foot of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount enclosure should be associated with the second phase, when Aelia Capitolina had been founded and the camp moved to the Temple Mount and to the foot of its southwestern corner.

A number of Latin inscriptions found in the excavations also bear witness to Roman rule in this area. One inscription on a column is inscribed with the name of a Xth Legion commander, as well as that of the emperors Vespasian and Titus. An identical column with the same inscription was recently found in the excavations of the Israel Antiquities Authority led by Ronny Reich and Jacob Billig in the same area.11

Moving the camp of the Xth Legion from the southwestern hill to the Temple Mount and the area below its southwestern corner must have been a central feature of the redesign of Jerusalem as the Roman city of Aelia Capitolina. If this occurred just before the Second Jewish Revolt broke out, moving the Xth Legion’s camp was no doubt considered a necessary response to the rising presence of rebels under the leadership of Bar Kochba, who surely longed to recapture the Temple Mount.

If the move came after the Second Jewish Revolt was suppressed, it was necessary for the same reason: Ultimate control over the area of the Temple Mount was necessary in preventing the Jews from recapturing the city. The enclosed, fortified Temple Mount was of utmost strategic importance in controlling the entire city.

We might never know with any certainty about the structures built by the Romans on the Temple Mount itself. The Roman historian Dio Cassius (second–third centuries C.E.) tells us that Hadrian erected a temple to Jupiter where the Jewish Temple once stood.12 It would have been an inseparable part of the assemblage of buildings and institutions that served the soldiers of the Xth Legion within their camp. The temple was complemented by an equestrian statue of the emperor himself. The anonymous Pilgrim of Bordeaux, who visited Jerusalem in 333 C.E. and left us his famous Itineraria, reports seeing two equestrian statues of Hadrian on the Temple Mount. The second one, however, was that of Hadrian’s successor, Antoninus Pius. The Bordeaux Pilgrim got confused because a dedicatory inscription on the base of the Antoninus statue used his full name, which, as Hadrian’s adopted son, included the name Hadrian. Some modern scholars have made the same mistake.13 We know of this inscription because it survives in secondary use in the southern wall of the Temple Mount just above the Double Gate.

Although more evidence will be required before any definite conclusions can be reached, a convincing body of archaeological and historical evidence already strengthens the suggestion that the Xth Legion camp was located on the Temple Mount and at the foot of its southwestern corner during the time when Jerusalem was a Roman city named Aelia Capitolina.

All uncredited photos are from the archives of the Temple Mount excavations, courtesy of Dr. Eilat Mazar.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

The material in this article will be published in full in Volume IV of the final report. The publication of the final report has been made possible by the Shelby White-Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications and the Beracha Foundation. The original manuscript on which this article is based was translated from Hebrew to English by Ben Gordon. Yiftah Shalev composed the isometric reconstruction of the bathhouse, with the assistance of Peretz Reuven. My thanks to all who have assisted and especially to Hershel Shanks for his support and continuing encouragement.

See D.T. Ariel, “A Survey of Coin Finds in Jerusalem (Until the End of the Byzantine Period),” Liber Annuus 32 (1982), pp. 273–301.

Orit Peleg, “Roman Engraved Gemstones for the Temple Mount Excavations,” in A. Faust and E. Baruch, eds., New Studies on Jerusalem, Proceedings of the Sixth Conference (Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan Univ., 2000), pp. 161–162. A thorough discussion by Orit Peleg on the gemstones will be included in the forthcoming final excavation report of the Roman period at the Temple Mount excavations.

Kathleen M. Kenyon, “Excavations in Jerusalem, 1964,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (PEQ) 97 (1965), p. 11.

Kenyon, Jerusalem: Excavating 3000 Years of History (U.K.: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1967), p. 189.

Kenyon, “Excavations in Jerusalem, 1966,” PEQ 99 (1967), pp. 69–70; Kenyon, “Excavations in Jerusalem, 1967,” PEQ 100 (1968), pp. 98–99.

On the eastern side of the corner, Kenyon uncovered a bedrock scarp hewn directly under and in alignment with the face of the wall, adding almost 20 feet to its height. At the foot of the scarp, she exposed a quarry on top of which were Byzantine buildings. Thus, Kenyon concluded that the original wall, reflected by the bedrock scarp, can be “sandwiched” chronologically between the southern Temple Mount enclosure wall of the Herodian period to which it adjoins and the Byzantine buildings alongside the bedrock face. In this way, she reasoned that the wall was originally the city wall of Aelia Capitolina (Kenyon, Jerusalem: Excavating 3000 Years of History, p. 90). I believe that the wall is not a city wall as posited by Kenyon, but was built with the founding of Aelia Capitolina in order to enclose the Xth Legion camp that was located at the foot of the southwestern corner of the enclosure.

Peretz Reuven, “The Bathhouse from the Temple Mount Excavations,” in Faust and Baruch, eds., New Studies on Jerusalem, p. 105 (Hebrew). A comparative study of the bathhouse plan has been carried out by Reuven and will appear in the forthcoming final excavation report of the Roman period at the Temple Mount excavations.

Noam Adler, “Stamped Tiles and Bricks of the Tenth Legion from the Temple Mount Excavations,” in Faust and Baruch, eds., New Studies on Jerusalem, pp. 120–124. A comprehensive study by Noam Adler on the Xth Legion stamp impressions from the Temple Mount excavations will appear in the forthcoming final excavation report of the Roman period at the excavations.

Ronny Reich and Jacob Billig, “Another Flavian Inscription Near the Temple Mount of Jerusalem,” ‘Atiqot 44 (2000), pp. 243–249.

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor questions the location of the temple to Jupiter at this site; he opts for the site of the later Church of the Holy Sepulchre as its location. See Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “Where Was the Capitol in Roman Jerusalem?” Bible Review, December 1997.

Gaalyah Cornfeld, The Mystery of the Temple Mount (Tel Aviv: Bazak, 1972), pp. 52–53. In his translation of the inscription, he omits the word “Antoninus”. See also Ronny Reich, Gideon Avni and Tamar Winter, The Jerusalem Archaeological Park (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1999), p. 35.