I first came upon the mountain in 1955, when I was conducting an archaeological survey in the Negev on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities. My specific interest was the virtually unknown rock art of the area—figures and signs engraved by ancient people on rocks. When I published Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Knopf, 1963), I devoted an entire chapter to this unusual rock art.a

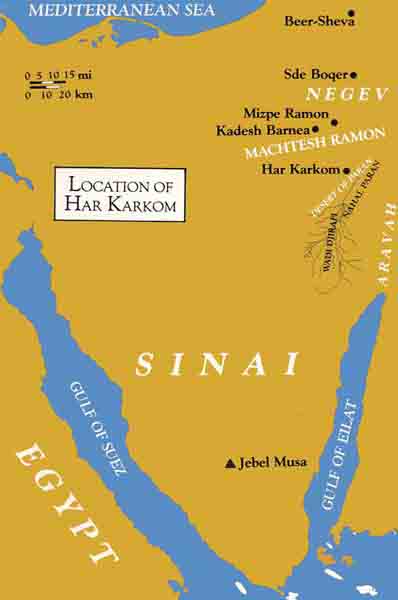

In 1955, I knew the mountain as Jebel Ideid. That is what the Bedouin called it. It was located in Israel just four miles from the border with Egypt, about 65 miles south of my field base at the young Kibbutz of Sde Boker, where David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, lived.

On this mountain I found the richest concentration of rock art in the Negev, located between the huge gorge known as the Machtesh Ramon and the Aravah Valley that extends from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Eilat.

While some of the styles and groups of rock engravings were similar to those I had found in the central Negev, others were quite different. Some assemblages, with which I was familiar, belonged to what is known today as Period III of rock art, the Chalcolithic Age (fourth millennium B.C.). These engravings included beautiful hunting scenes in which the hunters wore skin garments, used a bow and arrow, and were assisted by dogs. Other assemblages were also of a familiar character, showing a style known as Period IV-C, usually connected with the Nabataeans near the turn of the Common Era, and still others were inscriptions from Hellenistic and Roman times.

Between these two assemblages was another category of assemblage that was strange to me. It turned out to be a local version of the Period IV-A, from the Bronze Age (mainly from the third millennium B.C.). These assemblages depicted figures of worshippers standing before strange abstract symbols—for example, a figure of a praying man with upraised hands standing before a simple line. This theme was repeated several times.

From this same period, we also found some menhirs, or standing stone pillars. Menhir, an archaeological term, is the Breton word for standing stone; in the Bible such menhirs are known as masseboth (singular, massebah). Other discoveries included a peculiar stone structure with a courtyard and a rectangular platform facing east. Several tumuli (piles of stones that usually cover tombs) were also located on the mountain. One of these tumuli had a flat stone on top; beneath this stone was a large piece of a so-called “metallic-ware” jar that enabled us to date the tumulus to about 2000 B.C.

The mountain overlooked the Wadi Djirafi, in the area that Israeli geographical maps call the Desert of Paran. Hundreds of canyons wind through the hills of the desert. One can travel for miles without seeing a blade of grass. Ultimately, all the canyons, or wadis,b converge on the great wadi known as the Aravah, which extends south from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Eilat. It is a barren, powerful and essential land.

The view, as I stood on top of Jebel Ideid, was vast. To the south and to the east I felt as if I could almost hold in my hand the broken landscape going down to the Aravah and beyond to the distant hazy profile of the mountains of Moab and Edom on the other side of the great rift, in what is now Jordan. To the west the panorama encompassed the slopes and hills of central Sinai, crossed for thousands of years by caravans traveling between Arabia and the Mediterranean Sea on the spice route known as the Darb el-Aza. To the north I could see the mountains and valleys leading to the central Negev, and the watershed of the Machtesh Ramon.

Yet, with this immense landscape around me, I could see no sign of human life. The mountain on which I stood dominated an endless desert, an empty quarter of the world. The absolute silence was broken only by a sound like a prolonged explosion, as a mass of large boulders became detached from the wall of a precipice and fell into the valley.

The rock art on this mountain was strange to me for another reason. We knew of no other archaeological remains or rock art for miles around the mountain. Yet on the mountain itself and the areas leading up to it, the remains of human activity were all around. Why on this mountain? And what did all these indications of ancient human activity mean? I had no answers. Unfortunately, I was able to spend only one day on the mountain. But I knew that some day I would return.

In the 1970s, as head of the Italian archaeological expedition to the Near East by the Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, I decided to take the opportunity to visit Jebel Ideid again to study its archaeological remains more thoroughly and perhaps to answer some of the questions that had intrigued me nearly 20 years earlier. Strangely enough, however, I could not locate the mountain. Several attempts failed. The few Bedouin who had lived in the area whom I had known 20 years before had since moved on; there was no one left to indicate the route. New and more detailed geographical maps of the area had been made by the Israelis, but the name of this mountain, like many others, had changed. The new names no longer corresponded to those given to me by my Bedouin guides in the 1950s. And after 20 years, although I remembered the impact that the place had had on me, the landscape, the very atmosphere, and the rock art I had photographed and published, I could not recall details of the paths leading to the mountain. My staff and I tried repeatedly to find Jebel Ideid, but failed. It seemed simply to have disappeared.

Then, in 1980, 25 years after my previous visit, quite by accident, it was suddenly relocated.

Since then I have returned to the site many times—we have conducted 12 expeditions in the past five yearsc—but certainly nothing will ever equal the thrill of our rediscovery of the site in 1980. The only easy access to the mountain was through a large valley to the west; which can be reached only through a mountain pass that was very difficult to find until a trail had been clearly defined.

There is now a jeep trail to the site, and during our field season we have direct communications with Mizpe Ramon, the nearest permanent settlement some 62 miles away. On the new Israeli maps, the site is called Har Karkom, Mount Saffron in English. Henceforth we will refer to it as Har Karkom.

Strangely enough, despite the extreme elusiveness of the mountain, Har Karkom dominates the land around it, known as the Desert of Paran, and is, in fact, visible from a great distance. It can be seen from over 47 miles away, from the mountains of Edom in Jordan. Vertically, Har Karkom has a rectangular outline that imposes itself on the horizon and makes it an obvious point of reference for travelers crossing the desert even today, as it must have done for travelers in the past. Had we noticed this when we first found the mountain in 1955, we would have been spared a great deal of effort in relocating it.

For the most part, the trail to the western valley is relatively easy, although there is one difficult pass that must be negotiated with effort and care. Then the ground becomes extremely rough and uneven and cracked by erosion for a few miles.

The mountain itself consists of a limestone plateau (I shall refer to this plateau frequently) with outcrops of flint. It is quite large, measuring over 2.5 miles from north to south, and averaging 1.2 miles from east to west. Its maximum height is 2,795 feet above sea level, and it is almost completely surrounded by steep precipices.

On the plateau are two hills that rise 230 feet above the plateau. From the west they appear like the breasts of a large woman. Depressions and small valleys cover the rest of the plateau and descend toward the ravines to the west and southwest.

Har Karkom can be approached most easily from the west, because the precipices on the other sides are in most places too sheer to climb. On the west side, there are, in fact, two well-worn paths with some surprising features. One was partially cut by man at one point to facilitate the climb. Along the way are small caves that reveal distinct evidence of human presence and use.

The other path is even more surprising: On either side of it, for about one mile, are small rocks decorated with engravings. Many of them portray scenes of adoration—figures in the conventional praying position with upraised arms, before hermetic signs—signs clear only to those who have the key to understand them. In each of at least four cases, the praying figure stands before a vertical line. The scene appears to depict the worship of an abstract, unrepresentable deity.

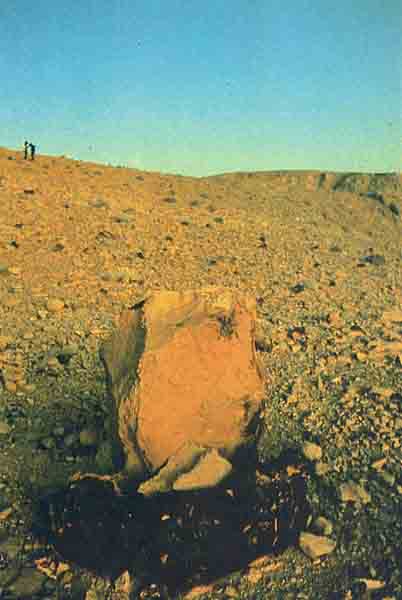

Along this path are also several orthostats, or menhirs, oblong standing stones intentionally set in vertical positions. Placed midway along the path, are a menhir and two smaller stones, at its base, engraved with figures. This grouping recalls a religious practice mentioned in the Bible: “And this stone which I have set for a pillar (massebah), shall be God’s house” (Genesis 28:22).

This winding path that leads towards the plateau resembles a kind of prehistoric Via Crucis, with stopping stations at which people carved the rocks with praying figures, erected masseboth, and perhaps performed other rites of worship as well.

At the foot of the mountain, where the two paths begin, is the western valley. Here our expedition set up its camp. Close by are vestiges of ancient walls and stone foundations, representing the encampments of peoples who stayed in this area ages ago. Above the valley rises the sphinx-like silhouette of the mountain, which our expedition climbed daily during our periods of field work.

This mountain and its surroundings have revealed to date over 400 archaeological sites, although it is situated in the middle of a wasteland that has otherwise provided us with very few archaeological remains during our quite thorough surveys of the surrounding area.

The exceptionally large number of archaeological finds associated with the mountain, the types of rock art and monuments, indicate that Har Karkom must have been a sacred mountain in ancient times, a place of worship of very great importance.

The wealth of rock art is extraordinary. On several clusters of rocky outcrops, we counted hundreds of engraved figures. All told, there are well over 35,000 engraved figures on Har Karkom. It is thus the major concentration of rock art known to us in the entire Negev.

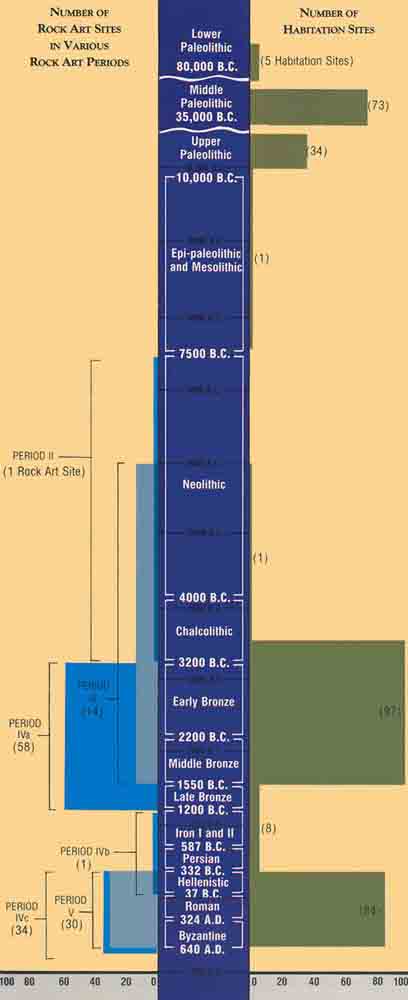

The figures are executed in styles and techniques already well-known elsewhere in the Middle East. As a result of our research, we have developed a chronology of rock art in the Negev and Sinai based on stylistic characteristics. A preliminary analysis of 138 rock art sites in the area of Har Karkom discovered up to June 1984 is summarized in the chart.

From the information on the distribution of rock art styles at Har Karkom, we can roughly trace the history of human activity at the site, even though there is considerable overlap in the periods assigned to each category.

The practice of engraving rocks started in this area in the Neolithic period, but it became widespread in the late Chalcolithic period (fourth millennium B.C.). The greatest creative activity is in style IV-A (58 sites), which dates to what archaeologists call the Early Bronze Age and Middle Bronze Age I (roughly the third millennium B.C.). Several thousand figures belong to this period.

Then there is nothing until the Hellenistic period. This gap—during the period of style IV-B—is extremely significant. It is a gap of roughly 1,600 years.

The same pattern is repeated when we focus on the archaeological remains instead of on rock art. Here again, the chart summarizes the evidence.

Although the Paleolithic period (80,000 to 10,000 B.C.) is not represented by any rock art, we did find a large number of virtually intact Paleolithic sites right on the surface of the plateau.

The remains of Paleolithic foundations of huts actually delineated the plan of the encampments. These huts are primarily oval-shaped. The inhabitants had cleared the huts of stones, and placed them around the outer perimeter of the encampment, no doubt to hold down the animal skins or other perishable material used as roofs for the structures. Within the encampment, we found flint-cutting workshops, with flint nuclei and flakes lying in situ, just as they had been left tens of thousands of years ago. The flint is of excellent quality; the large number of flint workshops suggests that it was this raw material that attracted Paleolithic people to the mountain. A single encampment, about 35 by 40 meters in size, consisting of eight huts, gives an idea of the amount of flint worked here. Within an area of 108 square feet on the edge of the settlement, we collected over 110 pounds of fine, elegant flint implements.

The archaeological evidence indicates that from the ninth to the fifth millennium B.C. there was very little activity on the mountain. Only one site yielded evidence of the presence of people during this period.

Toward the end of the Chalcolithic period (latter part of fourth millennium B.C.) and especially during the Early Bronze Age (third millennium B.C.), there is archaeological evidence of considerable activity at the mountain. On the plateau itself we found numerous remains of funerary and religious structures, as well as groups of tumuli and circles of boulders, which often enclosed standing stones (menhirs, or masseboth). Sometimes the rocks were engraved with decorations and figures. We excavated one of these tumuli and found a bundle of human long bones, a clear sign of secondary burial. The only object buried with these remains was a perforated shell-disk pendant.

We also discovered three larger stone structures from the Early Bronze Age. Each of these rather curious structures has a round courtyard in front of it. On one side of each courtyard is an altar-like platform. Two of these structures were found at the foot of the mountain in the western valley. The third is located in the center of the plateau, where it commands a beautiful view of the entire surrounding area. On the eastern side of each of these stone structures we found a number of masseboth. Masseboth were also found in front of and beside the altar-like platforms. On the far side of each courtyard was a small room, probably the only part of the structure that might have been covered by a roof. Rock engravings and funerary tumuli surround the structures. The nature of these buildings and their setting seem to indicate that they were small temples.

In the valley at the foot of the mountain, where the two trails to the top begin, we found traces of at least ten major encampments from the same period. We also noted several small lateral settlements, as well as one much larger central one (Site No. 50) that contained the remains of more than 50 groups of structures. Other camping sites were found along the wadi for some 4.5 miles northwest of the mountain. Apparently, a considerable number of people once lived at the foot of the mountain. On the mountain itself there are numerous Bronze Age sites of worship, and new camping sites are situated in the valleys at its base.

It is significant that these extensive remains are located in a desert area where, at least today, there is no trace of any oasis.

The artifacts from the sites of this period include both pottery and stone implements. Worked flint implements are characteristic of the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Ages; among those we found were blunt back-blades; several types of scrapers, including fan scrapers; notched implements and various kinds of pointed blades. We also found many re-tooled and reused flint implements that were originally made in the Paleolithic period but were re-worked in the late Chalcolithic period or in the Bronze Age. In fact, one of the recurring characteristics of these assemblages is the reuse of older implements. The lighter patina where the flint was retouched reveals the secondary use.

The majority of the pottery consists of minuscule sherds that have been dated mainly by Israeli archaeologists, led by Rudolph Cohen, the District Archaeologist for the Negev. Cohen’s team of experts dates the pottery to the Early Bronze Age II (2900–2600 B.C.) and the Middle Bronze Age I (2200–2000 B.C.). For both assemblages, the most common shape of pot is a hole-mouth jar with a flat base.

The dwelling structures seem to be characteristic of seminomadic, semipermanent populations. The houses had been reused more than once over the years. At several sites, pottery defined as belonging to the Early Bronze Age was found in the very same courtyards and rooms as pottery from the Middle Bronze Age I. Although pottery experts propose precise dates for these finds, one cannot exclude the possibility that in this area there was a direct cultural continuity between the Early Bronze II and Middle Bronze I period, as suggested by Cohen in this magazine two years ago.d

Further research might allow us to distinguish different phases within this culture. For the moment, we must refer to the material remains of these people at this time—including the entire assemblage of Early Bronze and Middle Bronze I artifacts—by the very general term BAC (Bronze Age Complex).

This complex undoubtedly reflects a tribal way of life, of communities living in marginal or peripheral areas. The organization of the sites indicates that these semi-nomadic, or semi-sedentary, people consisted of tribes organized in large family groups over a long period of time. The Chalcolithic flints suggest that this tradition goes back to the fourth millennium B.C. Most of it, however, can safely be attributed to the third millennium B.C.

The populations that lived in marginal areas like this must have been able to maintain their own traditions, almost completely uninfluenced by the agricultural and military upheavals that occurred in the fertile areas of Syria-Palestine. At present, this is just a working hypothesis, but it seems to fit the evidence.

It is perhaps significant that this mountain must have been an extremely important source of prime-quality flint in Paleolithic times. It appears to have become a holy place at the very end of the Stone Age, at a time when the use of flint as the material of primary daily use was drawing to a close. However, flint continued to be used extensively in the Early Bronze Age, and the quantity of very large and refined tools hints at its ritual use.

It appears, therefore, that Har Karkom was intensely occupied during the Paleolithic Age by hunting clans that collected and worked fine-quality flint in the area. The area was virtually abandoned in the Neolithic period; we found only one site from this period. Then, beginning in the late Chalcolithic or the Early Bronze Age, there was a period of intense occupation, reflected in the numerous religious and burial sites on the mountain and the dwelling encampments at its base. This period lasted for about a thousand years. During this time, the mountain was a place of worship, of pilgrimages, of religious rites and of funerary activities. After the Middle Bronze I period the site was again virtually abandoned—for the entire second millennium and for most of the first millennium—until the Nabataeans occupied the region.

Five years of archaeological investigation in this area produced an immense documentation on the way of life, the social structure, the economy, the habits and the beliefs of desert people in the course of these millennia.

It was clear from the very beginning of our survey that Har Karkom was a very important cult center in the third millennium B.C., a kind of prehistoric Mecca where large groups of people came and built their camps at the foothills and then climbed the plateau to worship. Menhirs, stone circles, tumuli, altar-like structures, peculiar round platforms with “altars” on top of them, were all clear indications of religious activities. Add to this the enormous amount of religious rock art and the remains of three small temples, and there can be no doubt that Har Karkom presents a unique aggregation of evidence of religious activity during the Bronze Age Complex. We know of no other site like it in the entire Negev and Sinai.

Har Karkom remained a great center of worship for at least a millennium before it was abandoned around 2000 B.C.

Although Har Karkom’s religious character was quite evident, I made no connection between that mountain and Mt. Sinai for several years. As an archaeologist, not a Biblical scholar, I never questioned that the Exodus had occurred in about the 13th century B.C. and that this was a firmly established fact. I had learned this date at school, from my textbooks, and had no reason to think otherwise. There was no evidence of any human occupation at Har Karkom in the 13th century B.C. or for centuries before or after. Indeed, the usual date for the Exodus occurred right in the middle of a long archaeological gap at Har Karkom.

Another factor that at first excluded any consideration of a relationship between Har Karkom and the Exodus was the location of the site, far from any previously proposed itinerary of the Exodus. Some scholars viewed the wanderings of the children of Israel in the desert as random movement from one well to another. Others saw it as consisting of an itinerary from Egypt south to the traditional Mt. Sinai located in the southern part of the peninsula, and from there to Ain Kudeirat, which is believed to be Kadesh-Barnea. Still others suggested the possibility that the Exodus itinerary described sites along the Mediterranean coast of northern Sinai. There were several other hypotheses, but none had considered our area.

Nevertheless, we thought it possible that such an important cult site on the edge of the Holy Land would be referred to in the Bible, if we could only figure out by what name. As archaeologists, however, this was not our primary concern.

I did, however, consult several colleagues who were Biblical scholars. I always received the same answer: The finds at Har Karkom were too early to have a Biblical connection. One of the greatest living Biblical scholars twitted me for exaggerating the significance of Har Karkom. The whole Sinai peninsula and the Negev were probably full of holy mountains, he told me, so we should not be bothered trying to identify Har Karkom in the Bible. To this I reacted very strongly; there was something wrong in this approach. I knew Sinai and the Negev very well. I had worked there for 30 years. I had never seen another mountain with such a tremendous amount of evidence of worship and of tribal gatherings as Har Karkom. It was hard for me to believe that such a site would not be mentioned in the Bible.

On the last day of our 1982 campaign—December 20 to be exact—I was climbing down the mountain as the sun was descending in the western sky Every stone was etched in sharp shadows. Suddenly, I saw the silhouette of a strange sequence of standing stones beside one of the archaeological sites near our camp. Although I had visited this particular site several times before, I had never noticed it in this light. The members of our expedition were packing and I made a short detour to examine more closely this structure at the edge of Site No. 52, one of the Bronze Age camp sites at the foot of the mountain. There was a group of 12 pillars or standing stones fixed vertically into the ground. Next to this group of masseboth were the remains of a structure that could not have been a dwelling place—it contained a platform and a courtyard. The surface finds did not indicate that it included any roofed rooms. This group of 12 pillars and the platform nearby vaguely reminded me of a passage in the Bible. I went on to our camp and took out a Bible and found the passage: “And Moses … rose up early in the morning, and builded an altar under the hill, and 12 pillars, according to the 12 tribes of Israel” (Exodus 24:4). Twelve is a recurring number in the Bible; it is, nevertheless, surprising that 12 pillars and a nearby structure were found “under [at the foot of] the hill [or mountain], at the edge of the camp site.”

I asked some members of my team to go to Site No. 52 with me and, standing there, I read them the passage from the Bible. We had a long discussion, and two additional items of interest came up, one relating to a cleft in the rock on the top of the mountain and the other to the small temple on the plateau of the mountain.

The cleft on the top of the mountain forms a small rock shelter that bears a striking correspondence to the cleft in the rock on the top of Mt. Sinai described in Exodus 33:21–22: “And the Lord said, Behold, there is a place by me, and thou shalt stand upon a rock; And it shall come to pass, while my glory passeth by, that I will put thee in the cleft of the rock, and will cover thee with my hand while I pass by. … ” To find such a niche or cleft on the very summit of a mountain is geologically quite unusual. I know of only one other such cleft on the top of a mountain: the cave on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, which is the traditional Mount Moriah, another very important holy place of Biblical times. On Mount Moriah, according to the Bible, Abraham offered to sacrifice his only son Isaac. Today the Dome of the Rock stands on this site sanctified by tradition.

The second item of interest that was raised in our discussion was the small Bronze Age temple at the center of the plateau of the mountain. In the courtyard of the temple was an elevated platform oriented toward the east. Surrounding the little temple were various funerary tumuli and rock engravings, as well as numerous carvings of footprints; those carvings are now known to be connected with worship. The Bible seems to make clear that Moses saw an old temple on Mt. Sinai, which he later used as a model and prototype: “And look that they make them after their pattern, which was showed thee in the mount” (Exodus 25:40). And “Hollow with boards shalt thou make it [the altar]; as it was showed thee in the mount, so shall they make it” (Exodus 27:8). The only area of this little sanctuary that seems to have been roofed was a small room, about 10 by 13 feet, with stone walls that originally must have been about five feet high. The roof was probably made of animal skins or some other perishable material. As the Bible describes it: “And thou shalt make curtains of goats’ hair to be a covering upon the tabernacle; eleven curtains shalt thou make” (Exodus 26:7). And further on: “And thou shalt rear up the tabernacle according to the fashion thereof which was showed thee in the mount” (Exodus 26:30). Some Biblical scholars believe that Moses may have had a vision of a “celestial” temple while on the mountain. Could it be possible instead that an ancient temple stood on the mount that the Bible describes as Sinai?

Among the cult sites on the plateau of the mountain there are numerous funerary tumuli. They suggest a specific burial custom in which the bones of the dead were preserved and eventually brought to be buried on such hallowed ground as this mountaintop. The Bible describes a similar practice, when the Israelites fleeing from Egypt carried the bones of Joseph with them: “And Moses took the bones of Joseph with him: for he had straightly sworn the children of Israel, saying, ‘God will surely visit you; and ye shall carry up my bones away hence with you’” (Exodus 13:19). Archaeological finds have shown that secondary burial under tumuli was practiced by Early Bronze Age cultures; and the practice came to an end at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age.

The rock engravings so abundantly represented at Har Karkom provide another intriguing comparison. As mentioned already, much of the rock art at Har Karkom can be dated to the Bronze Age. Many of these engravings contain occult signs that are incomprehensible to us now, but that must have had a specific significance for the people who executed them. In some cases, these engravings include series of parallel lines, or points, often eight or ten, perhaps indicating points to remember or memorize. Today, one might say, “Tie ten knots in your handkerchief” In one case, we even found an engraving of a rectangular stone tablet with two ear-like shapes on top. Lines divided the tablet into ten squares.

The Bible is not explicit as to what was engraved on the tablets containing the Ten Commandments. We are told that the two stones were later preserved in the Temple at Jerusalem. But nowhere are we told whether they were engraved with a script, either ancient Semitic or Egyptian, or with symbols or with simple markings. Any script would probably have been unintelligible to the majority of the Israelites fleeing from Egyptian slavery. It is quite conceivable that the Tablets of the Law were actually slabs of rocks engraved with symbols or markings not unlike those found along the paths and on the plateau of Har Karkom.

There are other aspects in which Har Karkom evokes Biblical descriptions of the Sinai event. For example, consider this description of the Israelite encampment at the foot of Mt. Sinai: “In the third month, when the children of Israel were gone forth out of the land of Egypt, the same day came they into the wilderness of Sinai. For they were departed from Rephidim, and were come to the desert of Sinai, and had pitched in the wilderness; and there Israel camped before the mount. And Moses went up unto God, and the Lord called unto him out of the mountain … ” (Exodus 19:1–3). Apparently, the Israelites camped in the desert facing the holy mountain. According to this description, the climb up to the mountaintop from the encampment must have been easily negotiated. This seems to correspond well with the layout at Har Karkom.

The Book of Numbers lists the names of stations of the Exodus and describes how the Israelites “ … encamped at Rephidim, where there was no water for the people to drink. And they departed from Rephidim, and pitched in the wilderness of Sinai” (Numbers 33:1–3). This undoubtedly refers to the encampment at the foot of the holy mountain, because Kivrot-Hataava, the following station along the route, was reached after the stay at Horeb (another name the Bible uses for Mt. Sinai) (Numbers 11:34).

A peculiar fact arises from this brief description: Having found no water at Rephidim, where there must have been a well, Moses turned toward a place in the desert that he probably knew had a good water source. Thus, the Biblical text suggests that even though the encampment at the foot of Mt. Sinai was in the desert and not in an oasis, there was still plenty of water there for the people to drink.

The situation described in Numbers 11 may apply to other places as well, but it is interesting to note that Har Karkom fits the description perfectly. There is an important water hole on the plateau. In addition, in the western valley at the foot of the mountain, there are several water holes (gevim) located below the cliffs. The rock there is quite impermeable and only a little rain is needed for the precipices above to become actual waterfalls. Around these water holes are the remains of small artificial canals that must have been built to collect rainwater even more efficiently. When kept in good condition, these water holes must have contained much more water than they are able to hold today.

The remains of campsites extend along Nahal Karkom (Wadi Ideid) for about 4.5 miles up to Beer Karkom (Bir Ideid), a perennial well where even during the summer the water level is only about 39 feet below ground level. Numerous important sites from the Bronze Age were found in this area. No doubt this desert region was able to provide sufficient drinking water for travelers throughout the entire year; even in this respect, Har Karkom satisfies one of the basic requirements for the location of Mt. Sinai.

Once we began looking for parallels between the Biblical descriptions of Mt. Sinai and our discoveries at Har Karkom, there seemed to be no end. For many years we had neglected the Bible. Now we had to ask ourselves: What is the meaning of all these similarities? Are they just intriguing coincidences?

The principal obstacle to identifying Har Karkom with Mt. Sinai seemed to be the date.

If we accept the date scholars usually assign to the Exodus, then we must dismiss Har Karkom as a possible candidate for Mt. Sinai, because nothing has been found there indicating a human presence during the 13th century B.C. or anytime near this date. If Har Karkom was Mt. Sinai and if the Exodus did indeed occur at that time, we should have found at least some vestiges of the campsites of the Israelites and some evidence of cult activities on the mountain from that period. But our discoveries at Har Karkom belong to the third millennium B.C.

However, my own re-study of the archaeological materials, a re-examination prompted by our discoveries at Har Karkom, has led me to the conclusion that on this point the exegetes may be wrong.

For the last few years, I have studied the Bible very thoroughly. The Bible speaks of several peoples other than the Israelites who lived in the desert at the time of the Exodus and had contacts with the Israelites. The Amalekites, who populated the central Negev and the Kadesh-Barnea area, for example, tried to stop the Israelites from entering the Promised Land: “Then came Amalek, and fought with Israel in Rephidim” (Exodus 17:8). The Midianites were another people, related to the Hebrews through Moses, who had frequent contacts with the wandering tribes of Israel (see, for example, Exodus 18:5). If the Biblical accounts are indeed based on fact, some remains of desert peoples like the Amalekites and Midianites should have come to light during the numerous archaeological surveys and excavations carried out in this area, but precious little has been found. In all eastern Sinai and the southern Negev there are no traces whatever that might indicate a human presence during the 14th and 13th centuries B.C., except some Egyptian mines that are unrelated to the Exodus.

By contrast, the entire desert area traversed by the Israelites, as related in the Bible, has yielded abundant archaeological remains from what I call BAC, or the Bronze Age Complex—the period of the Early Bronze Age and Middle Bronze I, roughly the third millennium B.C.

Kadesh-Barnea must have been the main tribal center during the Exodus, yet it has no trace of a Late Bronze Age (and in particular of a 13th-century B.C.) occupation. On the other hand, significant and abundant remains from the BAC have been recovered there, materials that are quite similar to those we found at the foot of Har Karkom.

The first two cities conquered by Joshua—Jericho and Ai—did not exist in the Late Bronze Age. The archaeological excavations carried out there over several decades by various expeditions have shown that both have clear and dramatic evidence of destruction and burning during the period of the Bronze Age Complex. Such archaeological discoveries conform quite well to events described in the Bible.

Archaeological surveys carried on in Jordan by Nelson Glueck and others have shown, in the BAC period, colonization that fits the Biblical descriptions very well. Nothing of the sort is known in the Late Bronze Age.

We could continue with other examples. We could talk about the excellent parallels between descriptions in Exodus and in the Egyptian literature of the First Intermediate period, but we shall stop here. If the narration of Exodus has any relation to actual events, the archaeological evidence indicates that the Exodus could only have occurred in the period of the Bronze Age Complex, in the third millennium B.C. The traditional dating of the Exodus is simply wrong.

There is however, another possibility: some scholars question whether the Exodus ever occurred. For them, it is an aetiological story—created to provide Israel with a national history. I do not, myself, accept this. As the great archaeologist Yigael Yadin used to say, “What kind of people would invent for themselves a history of enslavement and escape from slavery?” If stories were to be made up, we would expect a people to invent for themselves a more distinguished history.

But even if the Sinai event is an aetiological story, it must have drawn on elements of actual events. Some real events must have inspired the dramatic story of the holy mountain. It would be hard to find a better candidate for this mountain than Har Karkom.

Har Karkom was a holy mountain, a mountain of religious pilgrimage for a thousand years and more. This is strictly factual—and incontestable. The remains at the sites strikingly recall the story of Mt. Sinai in the Bible. But, is Har Karkom Mt. Sinai? The answer to this question is not factual, but conjectural. To say that it is Mt. Sinai requires a radical re-dating of the Exodus, and many scholars will be loathe to do this. But even if, to some scholars’ minds, the date of the Exodus cannot be reconciled with the date of the archaeological remains on Har Karkom, the nagging question remains: Isn’t there some connection between the two, between the unique event described so dramatically in the Bible and this unique holy mountain—unlike any other in the entire Sinai and Negev? Especially in light of the striking correspondences I have described, it seems to me that there must be a connection.

Much work undoubtedly remains to be done. But surely it is worthwhile raising questions.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

I have since continued my study of rock art in this part of the world and have recently published a monograph entitled “The Rock Art of the Negev and Sinai,” which has appeared in Italian, French and German, but not yet in English.

A grant from the Fondazione C.A.B. of Brescia, Italy, supported our research in 1983–1984. Some private donors in the United States and in Europe have also contributed to our efforts. But, on the whole, fund-raising is one of the most depressing jobs for an archaeologist, and funds are never adequate. In Israel, the research is carried on within the framework of the Archaeological Survey of Israel, in collaboration with the Department of Antiquities and Museums of the Ministry of Education and Culture.

The participants in this research include: Emmanuel Anati, director; Ariela Fradkin Anati, secretary; Gigi Cottinelli, Tiziana Cittadini, Ivonne Riano and Gianbattista Cottinelli, architects; Olga Pirelli, conservator; Avraham Hay and Daniel Anati, photographers; Larryn Diamond, geologist; Paola Pirelli and Giovanna Davini, botanists; Nancy Wise, recorder; Lucia Bellaspiga, Ida Mailland and Laura Valmadre, assistants. In addition, several of the expeditions were assisted by volunteers from the Field School of Mizpe Ramon; Gideon Avni and other archaeologists and guides from the Israel Department of Antiquities also helped us. In Italy, the cartography was carried on by Stefano Farina and Alessandra Angeloni; the analysis of aerial photographs by Tamar Piperna, the computerization of data by Franca Angeli and Antonio Guereira. A special acknowledgement is due to Rudolph Cohen, regional archaeologist of the Southern Region, and to Avi Eitan, director of the Department of Antiquities, for their support.

See “The Mysterious MB I People,” BAR 09:04.