Hebron Still Jewish in Second Temple Times

032

033

Hebron is mentioned nearly a hundred times in the Hebrew Bible.

One of the most impressive surviving ancient buildings in the Holy Land lies over the Cave of the Patriarchs (also called the Machpelah Cave). Resembling the now-destroyed Jerusalem Temple, this structure was built by King Herod the Great in Hebron over the traditional burial cave of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah (but not Rachel).

Yet a modern archaeological investigation in Hebron was not conducted until the mid-1960s. Neither then nor since has a comprehensive excavation been undertaken at the site.

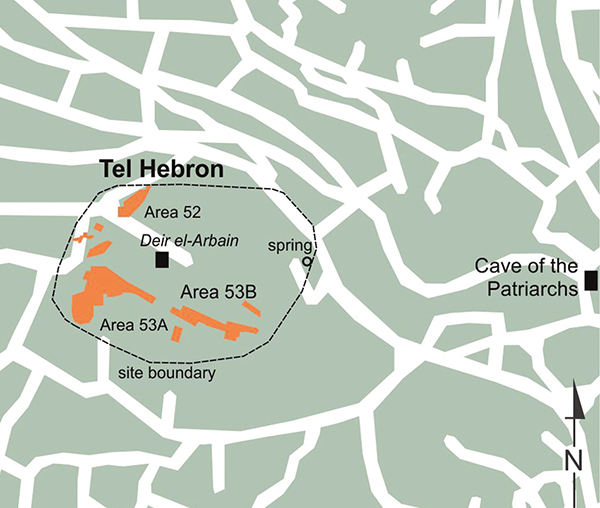

The Biblical town of Hebron is located on the less impressive and seldom visited tell nearby, Tel Hebron. The Second Temple period town was not excavated until 2014. Directed by Emanuel Eisenberg and myself, our expedition revealed evidence of a Jewish domestic and industrial quarter.1

Tel Hebron lies about 3,000 feet above sea level on a mountain spur overlooking the modern city of Hebron, some 20 miles south of Jerusalem. On 034its summit is an ancient structure known as Deir el-Arbain (the Monastery of the Forty), which is identified as the tomb of Ruth and Jesse, the great-grandmother and father of King David, according to Jewish tradition.

Hebron was—and still is—the major town or capital of the Judean hill country south of Jerusalem. The name Hebron (derived from the Hebrew ḥvr, meaning “friend”) is not mentioned in external texts and is known only from the Bible, where it is also called Kiriat-Arba or Mamre. Hebron appears as the family burial ground of the patriarchs and matriarchs (Genesis 23:1–20; Genesis 25:9–10; Genesis 35:27–29; Genesis 49:29–33), as an ancient and well-fortified city when the Israelites sent spies to Canaan (Numbers 13:22) and as King David’s first capital (2 Samuel 2:11), among other references in the Hebrew Bible. The archaeological evidence shows that the site was occupied and well fortified during part of the Bronze (c. 2500–2200 B.C.E. and 1750–1550 B.C.E.) and Iron Ages (ca. 1000–586 B.C.E.), but these periods are not the focus of this article. Our recent excavations have shed light on Hebron during the Second Temple period (mostly from 200 B.C.E. to 135 C.E.).

Hebron was probably destroyed by the Babylonians around 586 B.C.E. (the date of the destruction of the First Temple, which marks the end of the First Temple period). From about 500 years after the Babylonian destruction, we find remains of a well-built first-century B.C.E. town at Tel Hebron, which was still a major religious, economic and political center of Judah.

At this time, Hebron and its surroundings were considered to be part of Idumea. After the capture of Judah by the Babylonians, Idumea (Biblical Edom) expanded from southern Transjordan to the west and just north of Hebron—encroaching on the former territory of Judah.

According to Josephus, Simeon Bar-Giora, the Jewish rebel leader, conquered Hebron during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, but the Roman general Vespasian—who later became emperor—recaptured it and burnt it to the ground (Jewish War 4.529, 547).

I believe archaeology can now answer questions about the nature of Hebron and its surroundings during the Second Temple period and beyond (after 70 C.E.). Previous excavations hardly reported any significant remains from this period—even though the site clearly was occupied, according to pottery and other finds. Our recent 2014 excavation unearthed a large area with remains of a well-planned urban quarter with both domestic and industrial structures, located on the southwestern edge of the tell outside the ancient fortifications.

Four occupation phases were defined here from the Second Temple period: the time (1) of the late Hasmoneans (c. 100–37 B.C.E.), (2) of Herod the Great (37–4 B.C.E.), (3) of Herod’s sons until the First Jewish Revolt (4 B.C.E.–69 C.E.), and (4) between the two Jewish revolts (70–132 C.E.). This urban quarter was probably built during the Hasmonean period (late second–first centuries B.C.E.) after the Maccabean conquest. A thick massive wall segment—possibly belonging to a tower—which was only partly excavated, may indicate that the town was fortified by a wall built on top of the city’s earlier Iron Age wall.

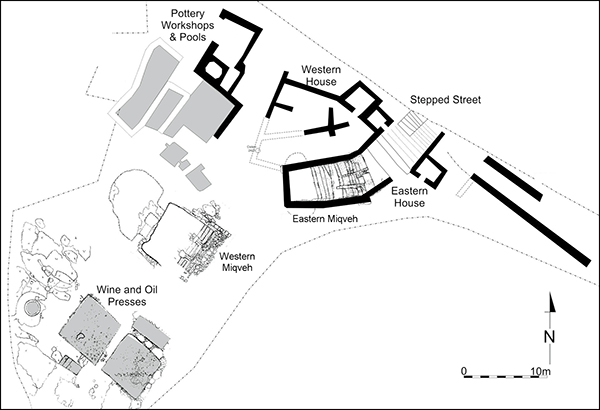

The domestic and industrial quarter included a wide paved stepped street that connected it to the upper tell, which was the center of the settlement (not excavated). Domestic houses were excavated on both sides of the street. The best-preserved architectural phase belongs to the period dating to Herod’s sons until the destruction during the First Jewish Revolt. One of the houses contained at least three rooms; underneath one of these floors, a complete jar was buried. Although the jar was found empty, originally it may have served as a safe for valuables 035or documents.

The second house, built west of the stepped street, had four or more rooms, one of which was the kitchen. Measuring 8 by 8 feet, it was a cellar-like room with three steps descending down to it. The kitchen was destroyed by heavy fire, which incidentally preserved a rich assemblage of complete pottery vessels and other finds. The vessels include a set of cooking pots, a stand, serving bowls of various sizes and a jug filled with burnt olives. The ground floor room above the cellar kitchen was not preserved, yet in the kitchen a collection of large nails coming from the wooden ceiling was found, as well as several storage jars coming from the room above. Near the door a curved iron key was found; apparently the key was still in the door when the house was burned during Vespasian’s attack in 69 C.E.

Near this house was an industrial area, well separated from the domestic zone. It included a pottery workshop, two winepresses and an open-air olive oil press.

The workshop included an oval kiln and a poorly preserved structure to the north that served as the potter’s workshop, where vessels were made. To the 036south a series of well-plastered pools were adjacent to the workshop. Constructed as large shallow pools, leading by channels into smaller, deeper pools, they were used to levigate and soak the potter’s clay. In this way, the coarser particles were soaked in the shallow pools, while the finer clay could be collected from the last deep pool (6 ft deep), which had two sets of narrow stairs going down to it. Some 50 yards to the west, an area with pottery slag (vitrified clay and vessels) and many pieces of pottery was found, which probably also belonged to this large industrial workshop. Considering that Hebron was a well-known pottery production center in ancient times, this find is not surprising.

On the southwestern edge of the excavation area, two large winepresses were discovered; they had two identical plastered square treading vats, measuring 20 by 20 feet. Into the nearby rock platforms, small cylindrical pits and channels were carved, and the area was used as an olive oil press. The oil would flow in the plastered channels.

One of the finds from this period was a beautiful silver coin, a half-shekel of Tyre (dated 12–13 C.E.).2 These coins were the hard currency of the time, and a half-shekel (equivalent to two drachmas) was exactly the annual tax per Jewish male at the Jerusalem Temple (originally mentioned in relation to the Tabernacle,Exodus 30:13). The Temple tax is also mentioned several times in the New Testament—for instance in the incident with Jesus and Peter at Capernaum: “When they reached Capernaum, the collectors of the Temple tax came to Peter and said, ‘Does your teacher not pay the Temple tax?’” (Matthew 17:24). Later Jesus sends Peter to collect a shekel coin from the mouth of a fish to pay for both of their taxes. Perhaps the coin found at Hebron was prepared by a Jewish resident to pay for his Temple tax on his planned visit to Jerusalem.

But was this settlement at Hebron Jewish—rather than pagan or Edomite? If it was Jewish, we would expect to find a small mikveh, a Jewish ritual bathing place usually consisting of a small stepped pool. Jews immersed in such pools—often daily or when needed—to be cleansed of impurities. These were common in nearly all Second Temple period Jewish settlements in Judea.

Without a mikveh (plural, mikva’ot), we hesitated to label the site Jewish.

As often happens, near the last days of the excavation, the most surprising, interesting and important discovery of the season—and the answer to our dilemma—surfaced. We had excavated two large pools with the remnants of an arched ceiling and stairs leading to them. The bottom of the pools had not yet been reached, and the stairs were blocked by a transverse wall, which was puzzling. Suddenly we realized that the arched ceiling and transverse wall were actually later additions (from the late Roman period), and underneath these were two large stepped pools, which we were able to identify 037as mikva’ot.

The eastern mikveh was a rectangular pool (24 by 14.5 ft) carved in the natural rock with 14 wide and well-plastered steps leading to it, more than 10 feet deep. This mikveh was a major feature of the site since the stepped street leads directly to it from the center of the site.

The better-preserved western mikveh had six steps and was nearly square (21 by 18 ft and at least 9 ft deep). It was connected by two rectangular openings to a large closed underground space (about 21 by 21 ft) carved in the rock. Although this mikveh has not yet been excavated completely, and its floor has not been reached, it is likely that the steps reached all the way to the bottom of the closed space, as is true of similar mikva’ot in the Hebron area.3

One may ask why these pools are identified as Jewish ritual baths at all, rather than water reservoirs or simply water installations. Archaeologist Ronny Reich of the University of Haifa has shown that the majority of the stepped pools in Judea during the Second Temple period and later should be identified as mikva’ot since they match the description of mikva’ot in the Mishnaic texts.4 These pools could not have been simply water reservoirs because the stairs highly reduce the pools’ capacity and, moreover, make the drawing of water inconvenient. Further, they do not fit any other function (e.g., as winepress vats). There is no other explanation for the well-smoothed finishing of the plastered walls and stairs of the pool other than preventing bathers from getting hurt when descending to be immersed—in the nude and often in the dark.

The two mikva’ot from Tel Hebron are special in several aspects. First, they are much larger than the private mikva’ot at Jerusalem and other sites; these at Hebron were apparently public installations. Their capacity was at least 2,825 cubic feet (about 20,000 gallons) each or, when completely full, more than 6,500 cubic feet (about 50,000 gallons). The reason for such large pools could have been related to the number of pilgrims coming from the nearby Cave of the Patriarchs, to a local custom of communal ritual bathing, or to the need of having a large enough space filled with water in the winter so that the mikva’ot would be still usable in the end of the rather dry Hebron summer.

Another unusual feature of these Hebron mikva’ot was the division of the wide stairs into three paths by two low plastered partition walls. We know of occurrences of a single partition wall, creating two lanes, in mikva’ot in Jerusalem and near Hebron. This has usually been interpreted as a way to separate the impure ones descending to be immersed and the pure ones ascending from the water. However, a mikveh with three lanes is known only from one other place: Khirbet Qumran, the site on the northern shore of the Dead Sea often linked to the Jewish sect of the Essenes and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Yet this feature is attested in both of Hebron’s mikva’ot!

The reason for the double separation is not clear. Perhaps the aim was to separate visitors with varying degrees of impurity, or possibly it was related to Hebron’s status as a Levite and priests’ town. However, what may be more significant are the resemblances between the Second Temple period sites of Hebron and Qumran. The similarities include the mikva’ot with a double partition on the stairs, a detailed water channeling system,5 the location of the mikva’ot in proximity to pottery workshops and the appearance of a special jar type—the archive or “scroll” jar, which is rare elsewhere. Archive storage jars were found at Qumran and at the nearby caves containing the scrolls. At Hebron several locally made examples of “scroll” jars were found, including complete vessels buried under floors.

Our new archaeological finds clearly show that Hebron was a Jewish town during the entire Second Temple period—and possibly slightly later. Several coins from the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.) and one coin from the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–135 C.E.) were found in the western mikveh. Not only did the town have large ritual baths but also chalk stone vessels, which cannot become impure according to Jewish law and which are a common identifier for Jewish sites.

The lack or near absence of imported ceramic 039tableware or containers is also characteristic of ancient Jewish settlements—due to Jewish purity laws that viewed imported pottery as impure and imported wine as not kosher.6

At Tel Hebron dozens of amphorae (storage vessels with two handles and a high neck) were found in a pit dated to the time of King Herod the Great (first century B.C.E.), together with many fragments of large storage jars. This deposit may have come from clearing a public storehouse from King Herod’s days. (Containing high-quality wine, these amphorae, nicknamed Kos-like amphorae, resemble similar vessels produced on the Greek island of Kos during the Persian and Hellenistic periods.) During the Roman period, this type of amphora became widespread throughout the Mediterranean, with several production centers attested. But, according to petrography (a microscopic method sourcing the vessel’s clay according to the minerals found in it), at Hebron all of the amphorae from the pit, which resemble imports, were made locally! It seems likely that these vessels contained locally produced, kosher wine for Jews—apparently imitating 064fashionable imported wines of the day.

This area of Tel Hebron was last occupied during the Late Roman period (c. 200–400 C.E.). At this time, the two large mikva’ot were converted into square water reservoirs and covered by an arched roof. One of the winepresses was reused, and the treading vat was repaved with a white mosaic. Near the site’s fortification walls a small house containing a flour mill was excavated. During these centuries, the settlement at Hebron was much sparser and reflected a rural agricultural village. Two cist graves lined with flat stones were found on the western edges of the site. In one, a young woman was buried with a complete glass bottle and several long iron nails; maybe this woman was crucified, or possibly the nails came from the coffin.

During the Byzantine period (324–638 C.E.), the pilgrimage of both Jews and Christians to Hebron (i.e., to the Cave of the Patriarchs) is mentioned in the sixth-century Itinerarium Antonini Placentini by the anonymous Piacenza Pilgrim. These texts describe a basilica containing the tombs of the patriarchs and the religious ceremonies held by both Jews and Christians on opposite sides of a partition wall.

Later the town of Hebron is frequently mentioned in various Arab sources from the early Islamic period (638–1099 C.E.), the Crusader period (1099–1291 C.E., when it was the seat of the Latin bishop), the Mamluk period (1291–1517 C.E.) and the Ottoman period (1517–1917 C.E.). During this last period, the tell was nearly abandoned and gradually became an area of olive groves. The new city of Hebron moved to the vicinity of the Cave of the Patriarchs where the “old” city of Hebron is known today, and the story of Tel Hebron finally ends.

Mentioned nearly 100 times in the Hebrew Bible, Hebron was a significant Biblical city. Recent excavations have uncovered the town from the Second Temple period. Its population—we can now confidently say—was still Jewish at that time.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

The final report of the excavation includes contributions by Rachel Bar-Nathan (pottery), Yoav Farhi (coins and metals), Daniel Vainstub (Hebrew epigraphy) and Ram Bouchnik (animal bones), among others.

See Ronny Reich, Miqwa’ot (Jewish Ritual Baths) in the Second Temple, Mishnaic and Talmudic Periods (Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2013), pp. 185–188.