“Something shiny caught my eye,” Dan Rodriguez recalls, reliving his moment of discovery. In June 1989, the 34-year-old Rodriguez—a pastor from Santurce, Puerto Rico—was walking down the steep path from the top of Herodium. He had just accompanied a group of Spanish-speaking students on an archaeological study-tour to this palace-fortress of Herod the Great, who ruled Judea from 37 to 4 B.C.a

Herodium, still dramatically intact today, was built by Herod in the Judean desert, nine miles south of Jerusalem, as a refuge from his political enemies and as the place where he wished to be buried. From a distance it appears to be a truncated, cone-shaped mountain. Recessed within the mountain’s flat top is Herod’s palace, with its Roman baths, elegant courtyard, synagogue and traces of painted frescoes on the walls. Earth piled up by Herod against the outer walls and towers of the palace-fortress created the distinctive smooth slopes of the mountain, so easily recognized on the southern horizon when viewed from Jerusalem.

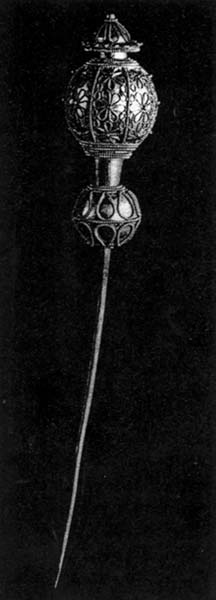

Rodriguez, who served as a translator for the tour group (the guide spoke in English), saw the glinting object protruding slightly from an earthen wall beside the road, about 200 yards below the guardhouse/ticket counter. “I didn’t pay much attention to it at first,” Rodriguez says, “because so often in digs it’s a pop top or a tack.” He was puzzled, however, about why the object was in the wall, 5 feet above the ground. Spurred by curiosity, he began picking at it with his finger. Then he pulled the object out of the wall and “realized it wasn’t a tack or pop top.” Carefully wiping the dirt off of it, he was surprised to find a tiny treasure. The object was gold! Measuring only 1.5 inches long, it consisted of a long wire, hooked on one end, with a bulbous, elaborately decorated ornament attached to the opposite end of the wire.

Rodriguez knew he had made an extraordinary find, but the excitement of the discovery was tinged with a little chagrin at having disturbed an artifact of some possible importance. “I wish I could have followed the correct archaeological procedure,” Rodriguez says, noting that he was not looking for artifacts and that the discovery was accidental.

Rodriguez carried the artifact to the waiting bus, where he showed it to Dr. Roy Blizzard, the leader of the study-tour. Blizzard examined the delicate object with astonishment and identified it as an earring. Later they took it to one of Blizzard’s friends, archaeologist Amihai Mazar of Hebrew University.

When Mazar saw it, Rodriguez recalls, he looked at it for a long, long time and then said, “This is a really nice piece.” He thought that it might be from the late Hellenistic or Herodian period (c. second or first century B.C.). Mazar suggested and arranged a meeting with Yael Israeli, then curator of archaeology at the Israel Museum. At the meeting, Israeli said the earring is significant because of where it was found and that the Israel Museum would like to acquire it. Rodriguez happily donated the earring because—as he explains—he is “against visitors taking artifacts out of the country of origin.”

Rodriguez later received a letter of thanks from Ruth Peled, chief curator for the Israel Antiquities Authority, as well as two books on archaeology in appreciation for turning in the earring. In the letter, Peled said, “The earring is attributed to the Hellenistic period.”

When Ami Mazar suggested to BAR that we publish an article on this discovery, he lamented that he knew of no specialist in Roman jewelry in Israel, but that he and his colleagues judged, “the earring is made in a tradition of gold jewelry work well known in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. It can easily be dated to the Second Temple period.” He also wondered, “Was it an item in the jewelry box of one of King Herod’s court ladies? Who can tell?”

One clue to the earring’s origin lies in the earthen wall where it was found. This wall stands at the foot of, and probably derives its earth from, the dumps left by Father Virgilio Corbo’s excavation, carried out from 1962 to 1965. These dumps consist of earth and stones thrown from inside the palace on the summit of Herodium. Thus, it is indeed conceivable that the earring may have once adorned a lady in Herod’s court.

In an attempt to better identify the earring, BAR solicited comments on the photo from an expert in Hellenistic jewelry, Dr. Stella G. Miller of the University of Cincinnati’s Department of Classics. She cautioned that judgments based on a photo instead of an examination of the object itself are not entirely reliable, and therefore her comments are tentative until she can handle the piece. Dr. Miller said:

“It doesn’t look like any standard sort of earring known to me. The bent wire, from what I can see of it, and the collar (the part between the wire and the ornament with the loops) are perfectly normal on a very common type of Hellenistic earring. But the collar typically ends in an animal head of some sort (a lion, bull, lynx, etc.) or, more rarely, in the head of a woman. I’ve never seen the rather floral type of ornament that we see here. This ornament is somewhat reminiscent of much earlier elements—floral-rosettes used on pin heads and earrings—but those have a quite different form. Possibly a repair that combined disparate elements was made to this earring in antiquity.”

This is not the first exciting find made by a tourist, nor is it likely to be the last. Long-time BAR readers may remember the case of the cuneiform tablet inscribed with the name of Hazor, which was found at Hazor in 1962 by Jesse Salsberg, a discovery that allows us to hope that a great archive may one day be found at Hazor.b That case exhibits a curious similarity to the present one in that Salsberg, like Rodriguez, accidentally found the inscribed clay fragment along a road he was descending while departing from the site. Fortunately the similarity ends there, as Rodriguez had no difficulty in locating someone willing to look at his find and donated the artifact under amicable circumstances to a grateful museum.

By contrast, Salsberg made his find in an era when there was comparatively little public awareness or concern regarding the removal of antiquities, and so he regarded the find as merely a curious souvenir. Only five years later did Salsberg suspect that the tablet might be important and attempt to find some expert who would look at it, a search that took three more years. Once the tablet was identified, someone alerted the Israel Department of Antiquities, which demanded the tablet’s return. Threatened with prosecution for possession of stolen property, Salsberg turned the tablet over to the Department of Antiquities in 1975.

Another significant find by a tourist, also at Hazor, was made in 1973 by six-year-old Elizabeth Shanks, daughter of BAR’s editor.c While searching with her family for potsherds lying loose on the surface, she found a pottery handle incised with a Syro-Hittite deity, dated to about 1400 B.C. The famous archaeologist Yigael Yadin, who had excavated Hazor, called the artifact “unusual and important” because it showed Hittite cultural penetration as far south as Hazor. Yadin also observed that young Shanks “spotted this handle at a place over which I and my fellow archaeologists walked many times without seeing it.” Yadin traded a Late Bronze II juglet for Elizabeth’s unique handle.

As these incidents show, even the casual tourist can make a contribution to archaeology simply by keeping alert. Whenever possible, however, the discoverer should leave the artifact undisturbed and notify the authorities. The thrill of discovery should exceed the vanity of possession for any true lover of archaeology.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Ehud Netzer, “Searching for Herod’s Tomb,” BAR 09:03.

See Hershel Shanks, “On the Surface,” BAR 08:02.