How Mute Stones Speak: Interpreting What We Dig Up

Footnotes

See Dan Gill, “How They Met,” BAR 20:04; Terence Kleven, “Up The Water Spout,” BAR 20:04; and Simon Parker, “Siloam Inscription Memorializes Engineering Achievement,” BAR 20:04.

See Hershel Shanks, “Yigael Yadin 1917–1984,” BAR 10:05.

The reference to “settlement archaeology” with a small “s” should be distinguished from the archaeology of the Israelite Settlement.

See Fredric R. Brandfon, “Archaeology and the Biblical Text,” BAR 14:01.

Endnotes

See Lewis R. Binford, In Pursuit of the Past (London: Thames and Hudson, 1983), especially pp. 19–26.

For brief summaries of the main tenets of the New Archaeology, see: Bruce G. Trigger, A History of Archaeological Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); Gordon R. Willey and Jeremy A. Sabloff, A History of American Archaeology (San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1974), pp. 183–208; Lawrence E. Toombs, “A Perspective on the New Archaeology,” in Leo G. Perdue, Lawrence E. Toombs and Gary L. Johnson, eds., Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation, Essays in Memory of D. Glen Rose (Atlanta: John Knox, 1987), pp. 41–52.

The “post-processual” or “contextual” archaeology is best represented by the works of Ian Hodder: Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991); Symbols in Action: Ethnoarchaeological Studies of Material Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); The Present Past: An Introduction to Anthropology for Archaeologists (London: Batsford, 1982). See also the volumes edited by Hodder: Symbolic and Structural Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); The Archaeology of Contextual Meaning (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); Archaeology as Long-Term History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

The most radical statements are by Michael Shanks and Christopher Tilley, Re-Constructing Archaeology, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 1992); Social Theory and Archaeology (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987). For critical discussions of these works see, for example, Kris Kristiansen, “The Black and the Red: Shanks and Tilley’s Programme for a Radical Archaeology,” Antiquity 62 (1988), pp. 473–482; Richard A. Watson, “Ozymandias, King of Kings: Postprocessual Radical Archaeology as Critique,” American Antiquity 55 (1990), pp. 673–689.

Julian Thomas and Christopher Tilley, “TAG and ‘Post-modernism’: A Reply to John Bintliff,” Antiquity 66 (1992), pp. 106–114.

William G. Dever, “Archaeological Method in Israel: A Continuing Revolution,” Biblical Archaeologist 43 (1980), p. 41.

This introduction to the intricate subject of interpretation in Biblical archaeology is indebted to the pioneer discussions of Neil Silberman, William G. Dever, Roger Moorey, Talia Shay and others who have laid the foundations of this new critical field of inquiry.

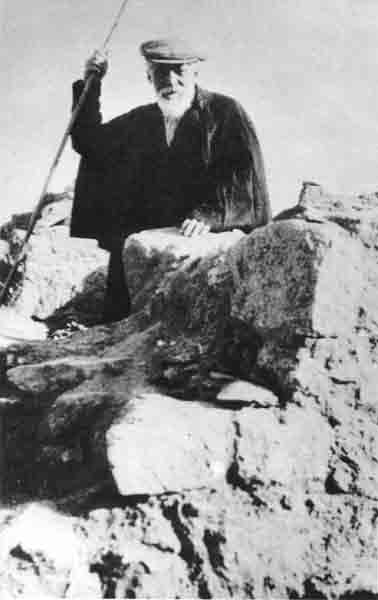

For the role played by these celebrated archaeologists in the history of Palestinian archaeology, see, for example, Joseph A. Callaway, “Sir Flinders Petrie: Father of Palestinian Archaeology,” BAR 06:06; Valerie M. Fargo, “BA Portrait: Sir Flinders Petrie,” Biblical Archaeologist 47 (1984), pp. 220–222; Margaret S. Drower, Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology (London: Gollancz, 1985); G. Ernest Wright, “Archaeological Method in Palestine—an American Interpretation,” Eretz-Israel 9 (1969), pp. 120*–133*.

See Neil A. Silberman, “Petrie and the Founding Fathers,” in Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990, Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), pp. 545–554. The following discussion is based on this most revealing essay.

R.A.S. Macalister, A History of Civilization in Palestine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1921), p. 31.

See Seymour Gitin, “Stratigraphy and Its Application to Chronology and Terminology,” in Biblical Archaeology Today, Proceedings of the International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, April 1984 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1985), pp. 100–101.

For Sellin’s work in Palestine, as well as for the Babel und Bibel controversy, see Silberman, Petrie and the Founding Fathers, pp. 548–549; P.R.S. Moorey, A Century of Biblical Archaeology (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1991), pp. 33, 44–47.

Israel Museum Journal 1987, p. 21. To his list of such erroneous interpretations one may add Duncan Mackenzie’s identification of ma

William G. Dever, “Syro-Palestinian Archaeology and Biblical Archaeology,” in D.A. Knight and G.M. Tucker, eds., The Hebrew Bible and its Modern Interpreters (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985), pp. 31–74. See also his Recent Archaeological Discoveries and Biblical Research (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1990), pp. 12–31.

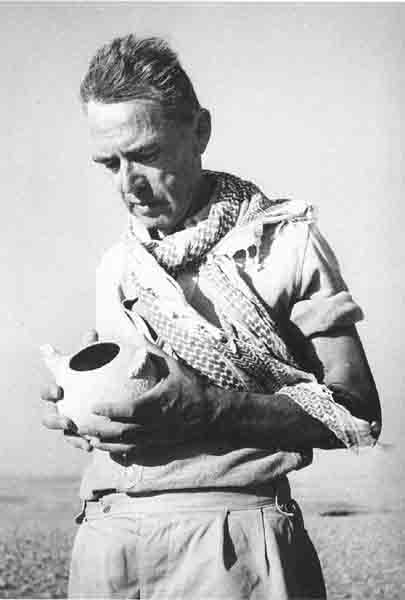

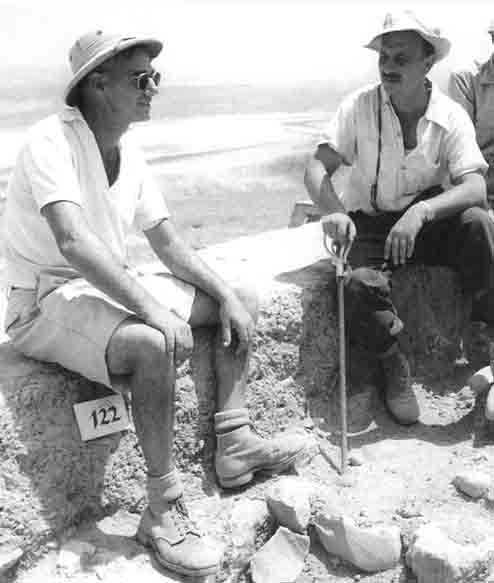

For Albright’s biography and appraisals of his scholarly work, see Leona G. Running and David N. Freedman, William Foxwell Albright. A Twentieth Century Genius (New York: Morgan, 1975); Gus W. Van Beek, ed., The Scholarship of William Foxwell Albright. An Appraisal (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989). Especially relevant to the present discussion are the critical articles by Jack M. Sasson, Neil A. Silberman, William G. Dever and Burke O. Long in Biblical Archaeologist 56 (1993).

H.J. Franken, “The Problem of Identification in Biblical Archaeology,” Palestine Exploration Fund 1976, p. 7.

Nelson Glueck, The Other Side of the Jordan (Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1970), Chapter 5. For a critique of Glueck’s interpretations, see James A. Sauer, “Transjordan in the Bronze and Iron Ages: A Critique of Glueck’s Synthesis,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR) 263 (1986), pp. 1–26.

Glueck, The Other Side, Chapter 4; Gary D. Pratico, “Nelson Glueck’s 1938–1940 Excavations at Tell el-Kheleifeh: A Reappraisal,” BASOR 259 (1985), pp. 1–32; “Where is Ezion-Geber? A Reappraisal of the Site Archaeologist Nelson Glueck Identified as King Solomon’s Red Sea Port,” BAR 12:05.

William F. Albright and James L. Kelso, The Excavation of Bethel (1934–1990), Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 39 (1968); and see William G. Dever’s critical review of the excavation report: “Archaeological Methods and Results: A Review of Two Recent Publications,” Orientalia 40 (1971), pp. 462–471.

On archaeology and the Patriarchs see William G. Dever, “The Patriarchal Traditions. Palestine in the Second Millennium B.C.E.: The Archaeological Picture,” in John H. Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller, eds., Israelite and Judean History (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1977), pp. 70–120, and the bibliography there. On archaeology and Israelite religion, see Dever, Recent Archaeological Discoveries, pp. 24–25 and Chapter 4; “The Contribution of Archaeology to the Study of Canaanite and Israelite Religion,” in Patrick D. Miller, Paul Hanson and S. Dean McBride, eds., Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988), pp. 209–247; John S. Holladay, “Religion in Israel and Judah under the Monarchy: An Explicitly Archaeological Approach,” Ancient Israelite Religion, pp. 249–299.

For the Wheeler-Kenyon method of excavation, see Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Archaeology from the Earth (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1956); Kathleen M. Kenyon, Beginning in Archaeology, 2nd ed. (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1971). For an appraisal of this method and of Kenyon’s role in Palestinian archaeology, see Peter R.S. Moorey, “Kathleen Kenyon and Palestinian Archaeology,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (1979), pp. 3–10; A Century of Biblical Archaeology, pp. 94–99, 122–126; Gabriel Barkay, “The Excavation Methods of Kathleen Kenyon,” Archaeologia 3 (1992), pp. 41–58 (Hebrew). For a comprehensive discussion of formation processes, see Michael B. Schiffer, Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987).

The normative model of culture is discussed in many of the essays collected in Lewis R. Binford, An Archaeological Perspective (New York: Seminar Press, 1972). See also Collin Renfrew, “Space, Time and Polity,” Approaches to Social Archaeology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1984), pp. 33–39. One of the best expositions of this model in the archaeology of Palestine is Kenyon’s textbook Archaeology of the Holy Land, 4th ed. (London: Ernest Benn, 1979).

See David Ussishkin, “Was the ‘Solomonic’ City Gate at Megiddo Built by King Solomon?” BASOR 239 (1980), pp. 1–18 and the bibliography there; John D. Currid, “Puzzling Public Buildings,” BAR 18:01, pp. 52–61.

Kathleen M. Kenyon, Amorites and Canaanites, The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy (London: Oxford University Press, 1966).

See Ofer Bar-Yosef and Amihai Mazar, “Israeli Archaeology,” World Archaeology 13 (1982), pp. 310–325; Ephraim Stern, “The Bible and Israeli Archaeology” in Perdue, Toombs and Johnson, Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation, pp. 31–40; Neil A. Silberman, Between Past and Present: Archaeology, Ideology, and Nationalism in the Modern Near East (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1988); Talia Shay, “Israeli Archaeology—Ideology and Practice,” Antiquity 63 (1989), pp. 768–772; William G. Dever, “Archaeology in Israel Today: A Summation and Critique,” in Seymour Gitin and William G. Dever, eds., Recent Excavations in Israel: Studies in Iron Age Archaeology, Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 49 (1989), pp. 143–152; Aharon Kempinski, “The Impact of Archaeology on Israeli Society and Culture,” Ariel 100–101 (1994), pp. 179–190 (Hebrew); see also the essays cited in the following note.

See

William G. Dever, “The Impact of the ‘New Archaeology’ on Syro-Palestinian Archaeology,” BASOR 242 (1981), pp. 15–29; “Archaeology, Syro-Palestinian and Biblical,” The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 1 (New York: Doubleday, 1992), pp. 354–367.

Even William G. Dever, once a proud and enthusiastic advocate of American-style “New Archaeology” in Palestine, admits now that “we also became enamoured of technical advances in archaeology for their own sake, and got bogged down in a morass of data often collected with no notion of what we were trying to learn,” in “Biblical Archaeology: Death and Rebirth,” in Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990, Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), p. 707.

For the towering figure of G. Ernest Wright, his theological approach to Biblical archaeology and the projects he initiated at the beginning of the 1970s in Israel, Jordan and Cyprus, see William G. Dever, “Biblical Theology and Biblical Archaeology: An Appreciation of G. Ernest Wright,” Harvard Theological Review 73 (1980), pp. 1–15; Recent Archaeological Discoveries, pp. 1–19; Philip J. King, “The Influence of G. Ernest Wright on the Archaeology of Palestine,” in Perdue, Toombs and Johnson, eds., Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation, pp. 15–29; and the articles in the 50th anniversary volume of Biblical Archaeologist, Biblical Archaeologist 50 (1987), pp. 5–21.

In a rare theoretical discussion, posthumously published (“The ‘New’ Archaeology,” Biblical Archaeologist 38 (1975), pp. 104–117), Wright delineated two necessities for future archaeological research in Palestine, clearly reflected in all the projects he initiated: (1) the embracing of the interdisciplinary approach; (2) better training and control in archaeological fieldwork prior to any theoretical discussion. His definitive dictum leaves no doubt that he saw in method and theory two distinctly separate realms: “Theorize all one wants, tightly controlled field method in extracting data from the ground is worth more than all pre-dig or post-dig theorizing put together…. The key to everything archaeological is the dirt work. Without sound control at this point, the theorists…who aspire to far too exalted a station to say anything about such trivial subjects as dirt methodology, are simply blowing hot air.”

See Binford, An Archaeological Perspective, pp. 129–130, 183. For a critical review of the implementation of the “New Archaeology” in Palestine, see my essay “The ‘New Archaeology’ and the Archaeology of Palestine,” Archaeologia 3 (1992), pp. 59–67 (Hebrew). One should note the hot debate about proper field methodology that raged at the beginning of the 1970s between American and Israeli Biblical archaeologists; see for example: Wright, Archaeological Method in Palestine; William G. Dever, “Two Approaches to Archaeological Method—the Architectural and the Stratigraphic,” Eretz-Israel 11 (1981), pp. 1*–8*; Yohanan Aharoni, “Remarks on the ‘Israeli’ Method of Excavation,” Eretz-Israel 11 (1981), pp. 48–53 (Hebrew). Evidently, the flagship of American “New Archaeology” in Palestine during the 1970s—the Gezer excavations—did not produce any innovative insights into the cultural systems of the ancient inhabitants of the site. Moreover, even the traditional “political history” of Gezer, reconstructed by the American excavators, became a perennial source of scholarly debate; compare, for example, two of William G. Dever’s articles written 20 years apart: “The Gezer Fortifications and the ‘High Place’: An Illustration of Stratigraphic Methods and Problems,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 1973, pp. 61–70, and “Further Evidence on the Date of the Outer Wall at Gezer,” BASOR 289 (1993), pp. 33–54.

35The Archaeological Survey of Israel is systematically published as a series of survey ‘Maps’ (1:20,000) by the Israel Antiquities Authority. For the hill country surveys, see mainly Moshe Kochavi, ed., Judaea, Samaria, and the Golan. Archaeological Survey 1967–1968 (Jerusalem: Archaeological Survey of Israel, 1972) (Hebrew); Adam Zertal, The Israelite Settlement in the Hill Country of Manasseh (Haifa: Haifa University, 1988) (Hebrew); Israel Finkelstein, “The Land of Ephraim Survey 1980–1987: Preliminary Report,” Tel Aviv 15–16 (1988–1989), pp. 117–183; Israel Finkelstein and Yitzhak Magen, eds., Archaeological Survey of the Hill Country of Benjamin, (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1993); Avi Ofer, “‘All the Hill Country of Judah’: From a Settlement Fringe to a Prosperous Monarchy,” in Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Na’aman, eds., From Nomadism to Monarchy. Archaeological and Historical Aspects of Early Israel(Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1994), pp. 92–121. Also see there the articles by Rafael Frankel, pp. 18–34 and Zvi Gal, pp. 35–46, as well as Zvi Gal, The Lower Galilee during the Iron Age (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1992), for surveys of the Galilee. For analysis of settlement and demographic data, see, for example, Magen Broshi, “The Population of Western Palestine in the Roman-Byzantine Period,” BASOR 236 (1979), pp. 1–10; Magen Broshi and Ram Gophna, “The Settlement and Population of Palestine during the Early Bronze Age II–III,” BASOR 253 (1984), pp. 41–53; “Middle Bronze Age II Palestine: Its Settlements and Population,” BASOR 261 (1986), pp. 73–90; Rivka Gonen, “Urban Canaan in the Late Bronze Period,” BASOR 253 (1984), pp. 61–73; Shlomo Bunimovitz, The Land of Israel in the Late Bronze Age: A Case Study of Socio-Cultural Change in a Complex Society (Ph.D. Thesis, Tel Aviv University, 1989), Chapter 3; Magen Broshi and Israel Finkelstein, “The Population of Palestine in the Iron Age II,” BASOR 287 (1992), pp. 47–60; Ram Gophna and Juval Portugali, “Settlement and Demographic Processes in Israel’s Coastal Plain from the Chalcolithic to the Middle Bronze Age,” BASOR 269 (1988), pp. 11–28; Israel Finkelstein and Ram Gophna, “Settlement, Demographic, and Economic Patterns in the Highlands of Palestine in the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Periods and the Beginning of Urbanism,” BASOR 289 (1993), pp. 1–22.

See, for example: Mocawiyah Ibrahim, James A. Sauer and Khair Yassine, “The East Jordan Valley Survey,” Bulletin of the American School of Archaeology 222 (1975), pp. 41–66; Robert D. Ibach, Archaeological Survey of the Hesban Region, Hesban 5 (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press); J. Maxwell Miller, ed., Archaeological Survey of the Kerak Plateau (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1991); Lawrence T. Geraty and others, eds., Madaba Plains Project 1 (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1989); Larry G. Herr and others, eds., Madaba Plains Project 2 (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1991); B. Macdonald, The Southern Ghors and Northeast cArabah Archaeological Survey (Sheffield: J.R. Collis Publications, 1992); and many of the recent publications in the Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

For the “coming of age” of American Biblical archaeology and for evaluation of other recent changes in the perspectives of Palestinian Biblical archaeology, see Dever’s essays cited in endnotes 7, 18, 19, 31.

On archaeology, history and the Annales school, see, for example, the bibliography cited in notes 4–5 and Bruce G. Trigger, “History and Contemporary American Archaeology” in Carl C. Lamberg-Karlovsky and Philip L. Kohl, eds., Archaeological Thought in America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 19–34; John L. Bintliff, ed., The Annales School and Archaeology (Leicester University Press, 1991); A. Bernard Knapp, ed., Archaeology, Annales, and Ethnohistory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); Knapp, Society and Polity at Bronze Age Pella: An Annales Perspective(Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), Chapter 2.

It should be noted that a “Braudelian” paradigm has long been practiced in the study of Israelite Settlement in Canaan in the guise of Albrecht Alt’s Territorialgeschichte. See especially his seminal article, “The Settlement of the Israelite in Canaan,” in Essays in Old Testament History and Religion (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1966), pp. 135–169, originally published in 1925.

The relation between ethnoarchaeology and Palestinian archaeology has been discussed by Dever in Archaeology in Israel Today, p. 147, and in “Archaeology, Syro-Palestinian and Biblical,” p. 357. The growing integration of ethnohistory within the archaeology of Palestine can be seen, for example, in Israel Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988); “A Few Notes on Demographic Data from Recent Generations and Ethnoarchaeology,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (1980), pp. 47–52. A more active field-oriented ethnoarchaeology is practiced in Jordan as exemplified, for example, by Oystein Sakala La Bianca, Sedentarization and Nomadization: Food System Cycles at Hesban and Vicinity in Transjordan, Hesban 1 (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1990).

See, for example, Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement; “The Emergence of Israel in Canaan: Consensus, Mainstream and Dispute,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 2 (1991), pp. 47–59; Lawrence E. Stager, “Merneptah, Israel and Sea Peoples: New Light on an Old Relief,” Eretz-Israel 18 (1985), pp. 56*–64*; Volkmar Fritz, “Conquest or Settlement? The Early Iron Age in Palestine,” Biblical Archaeologist 50 (1987), pp. 84–100; Dever, Recent Archaeological Discoveries, Chapter 2; “Cultural Continuity, Ethnicity in the Archaeological Record, and the Question of Israelite Origins,” Eretz-Israel 24 (1993), pp. 22*–33*; and the collection of papers in Finkelstein and Na’aman, eds., From Nomadism to Monarchy; For a review of recent research, see Hershel Shanks, William G. Dever, Baruch Halpern and P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., The Rise of Ancient Israel (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1992), especially the papers by Shanks, pp. 1–23, and Dever, pp. 26–60.

See, respectively, the papers by Israel Finkelstein (“The Emergence of Israel: A Phase in the Cyclical History of Canaan in the Third and Second Millennia BCE”) and Shlomo Bunimovitz (“Socio-Political Transformations in the Central Hill Country in the Late Bronze-Iron I Transition”), both in Finkelstein and Na’aman, eds., From Nomadism to Monarchy, pp. 150–178; 179–202.

William G. Dever, “Biblical Archaeology: Death and Rebirth,” in Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990. Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), pp. 706–722, and the bibliography cited there in note 8; Recent Archaeological Discoveries, Chapter 1; and “Archaeology, Syro-Palestinian and Biblical.”

See, for example, Bunimovitz, The Land of Israel in the Late Bronze Age; “Socio-Political Transformations”; A. Bernard Knapp, “Independence and Imperialism: Politico-economic Structures in the Bronze Age Levant,” in Knapp, Archaeology, Annales, and Ethnohistory, pp. 83–98; Society and Polity at Bronze Age Pella, especially pp. 13–14, for the reemphasis of the younger generation of Annalists on mentalités—ideology and symbolism within the cultural context.

See, for example, the exemplary essays by Lawrence E. Stager, “The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” BASOR 260 (1985), pp. 1–35; “The Song of Deborah: Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not,” BAR 15:01.

Brian Hesse, “Pig Lovers and Pig Haters: Patterns of Palestinian Pork Production,” Journal of Ethnobiology 10 (1990), pp. 195–225; Assaf Yasur-Landau and Shlomo Bunimovitz, “The Philistine Kitchen—Foodways as Ethnic Demarcators,” in Eighteenth Archaeological Conference in Israel, Abstracts (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Israel Antiquities Authority, 1992) (Hebrew); Ann Killebrew, “Functional Analysis of Thirteenth and Twelfth Century B.C.E. Cooking Pots,” lecture in the ASOR/SBL Annual Meeting (San Francisco, 1992); Israel Finkelstein, “Pots and People Revisited: Ethnic Boundaries in the Iron Age I,” in N. Silberman and H. Marblestone, eds., The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past/Interpreting the Present (New York: New York University Press, forthcoming); Shlomo Bunimovitz, “Philistine and Israelite Pottery: A Comparative Approach to the Question of Pots and People,” lecture in the ASOR/SBL Annual Meeting (Chicago, 1994, forthcoming).