“What must I do to inherit eternal life?” the man of the law asks Jesus.

“What is written in the law? What do you read there?”

And he answered: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might; and your neighbor as yourself,” quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18.

And Jesus responds: “You have answered right; do this, and you will live.”

Quibbling, the lawyer replies: “Who is my neighbor?”

Then Jesus tells him the parable of the Good Samaritan. “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers who stripped him and beat him and departed leaving him half dead.” A priest passed by but did not stop. A Levite, the same. A passing Samaritan, however, had compassion on the man and “bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; then he set him on his own animal and brought him to an inn.”

And Jesus said to the lawyer, “Go and do likewise.”

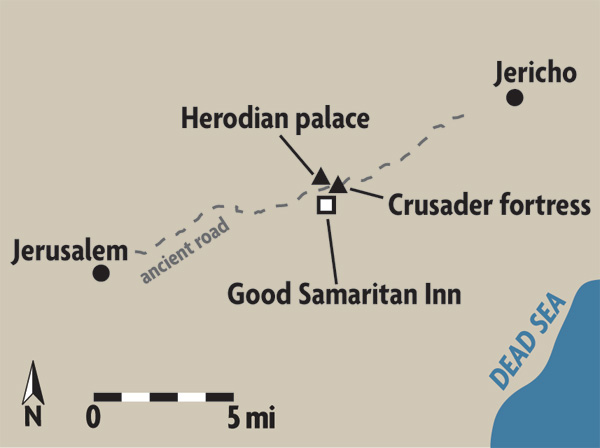

But where exactly was the inn? Luke 10:25–37 does not tell us. All we know is that it was probably on or near the Jerusalem-Jericho road.

No text until the fifth century provides us with an answer. In the late fourth century, the erudite Church Father Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin (known as the Vulgate, because Latin was a vulgar, or common, language at the time), traveled to sacred sites with Paula, a woman of a Roman senatorial family who had moved to the Holy Land and built a monastery in Bethlehem. In 404 C.E., in a letter to Paula’s daughter after Paula had died, Jerome located the Inn of the Good Samaritan:

She [Paula, traveling with Jerome] went directly down [from Jerusalem] to Jericho, recalling the Gospel account of the man who was wounded. The priest and the Levites cruelly passed him by, but the Samaritan [“the Guardian”] in his mercy took the man at the point of death, and set him on his beast, and carried him away to the inn, the church, and she considered the place called Adummim [“of blood”] because robbers make so many attacks there and so much blood is shed.1

In his Latin translation of Roman historian and Church Father Eusebius’s Onomasticon, Jerome says the site of Adummim can also be called “the Ascent of the Reds or the Blood-Stains, because of the blood that has been shed there by robbers. For it is at the border of the tribe of Judah with Benjamin, on the way down to Jericho from Aelia [Aelia Capitolina, as the Roman emperor Hadrian had renamed Jerusalem in the second century C.E.], where also there is a military post situated to help travelers. The Lord is also recorded as mentioning it as a cruel and blood-stained place in a parable of the man going down to Jericho from Jerusalem.”2

This is the first time the site of the inn referred to in Luke is identified. Here it is called a military post “to help travelers” and identified with the Biblical site of Ma‘ale Adummim (Joshua 15:7, 18:17), the ascent or height of Adummim. One etymology of the name Adummim is that the wadi or dry stream bed that marks the border between Judah and Benjamin features reddish (adamdam in Hebrew) rocks on both sides. But Ma‘ale Adummim was also apparently a place plagued with robbers where much blood was shed even in the time of Joshua; hence the reference in the etymology of Adummim as blood (dam means “blood” in Hebrew). With good reason, Jerome reports a military post there. As noted above, Jerome also refers to a church (more on this later) as well as an inn at the site.

The site Jerome refers to is located at the midpoint of the main road from Jerusalem to Jericho, a total distance of 16 miles. For thousands of years this route connected Jerusalem with the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea. In the First Temple Period (c. 1000–586 B.C.E.) it was known as the ‘Arava route (Deuteronomy 2:8; 2 Samuel 2:29, 4:7; 2 Kings 25:4; Jeremiah 39:4, 52:7). Herod the Great, as well as the Judean kings of the Hasmonean line before him, built palaces in Jericho,a at which time the Jerusalem-Jericho route assumed even greater importance. Traffic reached its peak, however, from Christian pilgrimage that continued throughout the Byzantine period as well as during the Crusader period. Pilgrims would come from Galilee down the Jordan Valley and from Jericho up to Jerusalem.

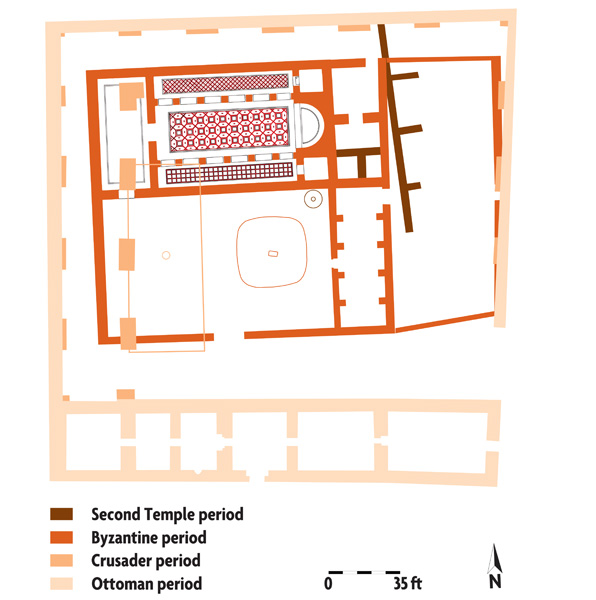

We have been working here since 1998. It was clear from the outset that this was no ordinary archaeological site; it is not an ancient settlement with stratigraphical levels defining the various time periods. On the contrary, the site had been only a way station for travelers—a khan (from the Arabic)—overlooking the Jerusalem-Jericho road below. It was a khan at the beginning and that’s what it has been into modern times.

The latest khan here was built by the Ottoman Sultan Ibrahim Pasha in the 19th century, and has undergone major changes over time. The building originally consisted of six halls, the easternmost one of which had been destroyed by the time we began our work at the site. We decided to reconstruct the destroyed hall, but with steel and glass instead of stone, for reasons that will become clearer later in this article.

In front of the entrance to the structure is a beautiful, even romantic, eucalyptus tree. Eucalyptus trees are not native to Israel. They were brought from Australia because they were very good for drying up swamps in several parts of the land. A eucalyptus tree was certainly not needed at the Inn of the Good Samaritan, however, where the rainfall averages only 4 inches a year and the land is hot, parched and dry. How this eucalyptus tree happened to get here remains a mystery. Even more of a mystery is how it survived. We have been giving it special care, however, and it is now thriving. Its seeds have even taken root in the soil and begun to sprout.

Northwest of the inn, on the other side of the modern road, Herod the Great built a palace with a bathhouse adorned with mosaics, stucco and frescoes. Unfortunately, the palace sustained severe damage from the construction of a later Crusader fortress.b On the hill northeast of the khan are the remains of another Crusader fortress known as the Tour Rouge, or Red Tower. A stone staircase led to the roof, which commanded a dramatic view of the road. The tower was surrounded by three lines of defense: an encompassing moat; a wall protecting the moat; and slightly pointed barrel vaults enclosing the southern and western sides of the fortress, where the walls were most easily accessible. It was built by the Templars to protect pilgrims and replaced an earlier Byzantine fortress built for the same purpose.3

Surprisingly, we found no archaeological remains from the First Temple period in our excavation near the inn. From the Second Temple period we unearthed numerous remains of walls from structures that were erected at the top of the ascent, many of them in caves dug in the soft limestone. In the Roman period, a military fortress (Castellum militium) was built at the site, and in the Byzantine period, a way station was established, with a large basilical church and accompanying service rooms and stables for wayfarers.

The scant remains of this Byzantine church where pilgrims prayed are immediately north of the inn. In 1934, the Byzantine church’s mosaic floor was uncovered. Since then, pilgrims have been taking tesserae of the mosaic as mementos. Gradually the mosaic floor was disappearing. Nearly 70 years later, little of the mosaic was left. However, we found some old photographs of it from the period of the British Mandate of Palestine that revealed what the mosaic looked like before it was vandalized. It was composed of familiar geometric designs.

At this point, we took a bold step. We decided that, instead of simply leaving the few remaining patches, we would reconstruct the entire floor. We also decided to follow the same methods, using the same features that were used in antiquity. We made a bed of stones in cement, using cement similar in composition to that of the Byzantine period. We poured bonding agents on the tesserae similar to that used in the original.

Creating the new tesserae proved to be a major hurdle. Just acquiring the right shades and colors of stone was complicated. Many hues of white stones and many shades of black, red and other colors were required. We searched throughout Israel to find suitable stones.

Initially, we even cut the tesserae by hand. This gave us an added appreciation of the skill and effort required to create a mosaic floor in antiquity. Realizing that we would need two million tesserae to complete the restoration, at one point we decided to purchase an electric stone saw.

The restoration of the Byzantine mosaic floor led us to another decision. We had acquired a dedicated, skilled team of workers who learned to restore the mosaic. Why not create a mosaic museum at the site? This would be the only one in the Holy Land. Inasmuch as the parable of the Good Samaritan was recorded by the emerging Christian community and mentions both Jews and Samaritans, we decided to incorporate this tripartite feature into the museum display: We would display mosaics from both Jewish and Samaritan synagogues and from Christian churches, as well as other artifacts.

The Samaritans, with roots in Judaism, were the first to separate from the mother faith. The Christians were next. The Samaritans trace their roots as a remnant of the northern kingdom of Israel. The Samaritans separated from the Israelites after the Assyrian destruction of Samaria in 722 B.C.E. In 586 B.C.E. the Babylonians destroyed Judah and exiled the Judahites. When the Persian monarch Cyrus the Great permitted the exiles in Babylonia to return to Zion in the sixth century B.C.E., two different “Judaisms” were created: the Samaritans in Samaria and the Judeans in what was now Judea. The Samaritans built their temple on Mt. Gerizim;c the Judeans on the site of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. The Samaritans remained close to Judaism, however (their Holy Scriptures consist of the Pentateuch with some variations), and their synagogues are similar to Jewish ones.4

Early Christianity also had its roots in Judaism. The Hebrew Bible was translated into the Greek Septuagint and retained as part of the Christian Holy Scriptures (the Old Testament). But Christian houses of worship are quite different from synagogues.

The mosaics on display in the museum come from Judea, Samaria and Gaza.5 Many had suffered serious damage in recent years. Removing them to our museum, where they were treated to preserve them, protected them in a way that could not be provided at their sites. Most of the mosaics on display from Christian churches had been uncovered in salvage excavations after the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement of 1995.

Oddly enough, it was the Jewish synagogue mosaics that were most difficult for us to obtain for the museum. Not that there were so few of them, but they were either already on display at other museums or were displayed in situ. To remedy this scarcity, we created replicas of three well-known synagogue mosaics. The Israel Museum’s reconstruction of the mosaic from the sixth-century Gaza synagogue featuring King David was recently described (and pictured) in BAR.d We made a replica for our museum. The others in our museum are the sixth-century Jericho synagogue mosaic inscribed shalom al Israel (“peace upon Israel”) and an inscription from the sixth-century Susiya synagogue, south of Hebron, which includes the same phrase.

The entire museum and its contents are the work of our small team, often venturing into unknown territory. The design of the museum evolved gradually. It was at this point that we decided to replace the missing hall of the inn with a glass and steel structure in which to display the mosaics.

We not only planned the museum and the display, but we even wrote the captions to the objects. None of us had been trained to plan museums, but the results pleasantly surprised us. We all learned as we progressed. The workers who had reconstructed the mosaic from the Byzantine church were especially valuable because their work on that mosaic taught them how to preserve and protect the other mosaics on display.

Thousands of tourists continue to visit our museum. It is user friendly, quiet and refined. The mosaics are displayed in two groups: one group is outside, in the open; the other is in the museum building. The site is infused with sanctity, humility and tranquility.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Suzanne F. Singer, “The Winter Palaces of Jericho,” BAR 03:02.

The palace was recently excavated by Yuval Peleg on behalf of the Staff Officer of Archaeology—Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria, Yitzhak Magen.

See Yitzhak Magen, “Bells, Pendants, Snakes & Stones—A Samaritan Temple to the Lord on Mt. Gerizim,” BAR 36:06.

See Strata: “King David Gets a Facelift,” BAR 37:01.

Endnotes

G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville et al., eds., The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea (Jerusalem: Carta, 2003), pp. 21–22.

Jerome, Onomasticon, 611; see also E. Klosterman, trans., Eusebius Werke: Das Onomastikon 119.4–6, 173.27 (Leipzig, 1904). The Tour Rouge was recently excavated by Yitzhak Magen, Yuval Peleg and Uzi Greenfeld of the Staff Officer of Archaeology—Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria.

For further reading on the Samaritans and on the Good Samaritan Inn, see Yitzhak Magen, The Samaritans and the Good Samaritan, JSP 7, (Jerusalem: IAA, 2008).