Jerusalem Couple Excavates Under Newly Built Home in Search of Their Roots

Residence to become museum to display finds

044

“Pouring into the alleys [of the Upper City], sword in hand, they massacred indiscriminately all whom they met, and burnt the houses with all who had taken refuge within. … running everyone through who fell in their way, they choked the alleys with corpses and deluged the whole city with blood, insomuch that many of the fires were extinguished by the gory stream.”a

Two thousand years later Theo Siebenberg stared in amazement at the perfectly formed skull that he knew must have belonged to a Jewish resident of the Upper City at the time of the bloodbath that climaxed the calamitous rebellion of the Jews against their Roman masters.

Siebenberg, who as a boy of 13 had fled Belgium with his family, one step ahead of the Nazi onslaught, suddenly found himself in tears.

“I had a feeling of looking at myself, as if his life and mine were one, directly and inevitably connected,” he remembers. At that moment, a worker reached to pick up the skull. “Don’t touch it!” Theo warned. But it was too late. The skull crumbled into ashes, fragments of history that had held together inexplicably for just such a moment.

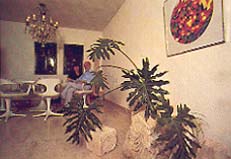

Theo Siebenberg is a cultivated and gentle man of 55 who lives with his wife Miriam in the same Upper City that was destroyed two millennia ago and is known now as the Jewish Quarter of the old walled city of Jerusalem. His splendid four-level stone residence rises to a roof-top garden that commands a majestic view of the Jerusalem landscape, encompassing the Kotel or Western Wall square, Mount Scopus and the Mount of Olives. Theo and Miriam Siebenberg live the good life. But Theo is a man obsessed. He is a digger. For ten years he has been digging—at a personal cost of $2 million—in the bowels of the earth beneath his home.

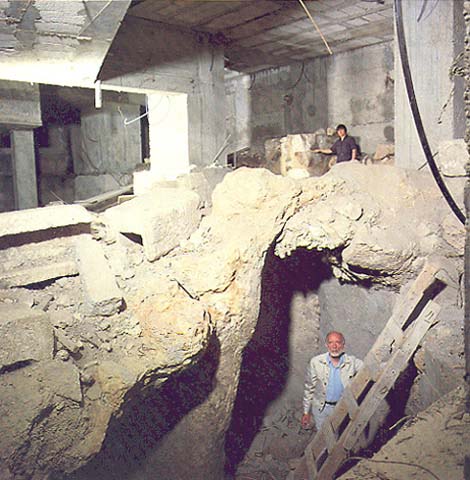

With the help of a privately-hired force of architects, engineers, contractors, laborers and against the advice of archaeological experts, Theo Siebenberg dug to find evidence of an earlier civilization under his feet. He dug to find a direct link with his Jewish past. And find it he did. He found the base wall of the home of his wealthy predecessor—2,000 years removed—whose mansion occupied this very site. He found artifacts—hundreds, he says, some of them on display in a showcase in his home—that confirmed the genteel lifestyle of that earlier, ill-starred family. He found ritual mikvah baths, indicating the family’s possible priestly connection. And, going even deeper—some 60 feet deep—he discovered burial chambers dating to the First Temple era at least 2,600 years old, complete with supporting walls covered with original plaster.

The Siebenberg excavation is not only a monument to determination and plain bull-headedness, but an engineering and structural marvel. The structural problems were enormous, given that the full weight of the Siebenberg home rested on the mound that was to be excavated. Modern techniques involved painstakingly installing huge slabs of concrete, massive steel anchors, and the use of a low Caterpillar from King Solomon’s Mines at Timna, in order to squeeze into tight spaces of the dig. It was slow, laborious work.

And now, based on his findings, and a desire to share them with the world, Theo is constructing an elaborate four-level museum under his home. Exhibits will evoke the style of life of the Second Temple family against a multi-media, audio-visual backdrop placing that lifestyle in broader historical context.

For awhile, Siebenberg’s odyssey seemed more Siebenberg’s Folly—and Theo a latter-day Quixote tilting at sandhills with a shovel. Besides the archaeologists’ skepticism, engineers and architects also told him it couldn’t be done—at least not without spending vast sums of money.

Why do it? And why stick to it for ten often discouraging years? The answers are obscured by the reticence of an essentially private man. But it seems clear that for Siebenberg the project represented the culmination of a restless search. Uprooted from pre-war Antwerp, he wandered from 046country to country for many years. Until he planted himself in the soil of old Jerusalem, Theo Siebenberg, one imagines, felt dispossessed. It was a natural step, then, to dig down, seeking deeper roots, seeking to reconnect with the wellspring.

“I felt I owed a debt to those who fought here,” he says, seated in his comfortable living room surrounded by antiquities, Oriental rugs and his wife’s colorful abstract paintings. “That gave me the idea of bringing the house back to life. It’s almost as if I had to get even with Titus (the Roman general) who destroyed all this.”

Theo’s search for continuity stems from 1939, when he and his once-wealthy family became fugitives, hopskipping from Antwerp across Europe, narrowly escaping death.

“I was arrested. My father, my brother were arrested on different occasions. My father was remarkable. He went back into occupied territory to get one of my brothers out. He took us through France … we were on roads being strafed by machine guns. Planes were bombing us.”

They made it to America where Theo tried with difficulty to adjust. As soon as the war ended, he returned to Antwerp to find it remarkably the same physically but changed forever in many other ways. He vacillated between Europe and the United States. “I couldn’t make up my mind where I wanted to stay.”

Always attracted to Israel, he joined the Stern Group in Europe in 1946 and, at the age of 20, smuggled people across borders and bought arms for Israeli partisans.

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Theo visited Israel for the first time, the first of many trips over several years. During that period he became involved in international business that kept him going from country to country In 1963 he met his wife, Miriam, an outspoken, dynamic Israeli-born woman.

The couple lived in Haifa until the 1967 war, when old Jerusalem was captured from the Jordanians. The Siebenbergs felt drawn to the Old City, to the old Jewish Quarter. Theo chose a site and hired an architect (Yaakov Ya’ar, who is also designing the museum).

Bulldozers cleared the rubble that was left of the Jewish homes that had been destroyed during the 19-year Jordanian occupation. Then excavation began for the concrete piers that the architects and engineers said were necessary to support the new four-story house to be built on the site. Inspectors from the Department of Antiquities kept an eye on the work, which would be stopped if the area appeared promising for archaeological excavation.

When Antiquities Department inspectors check sites, “in two out of three cases something does turn up,” Theo says. “I was intrigued by this prospect and half hoped that construction would be stopped. I invited the inspectors back to the site more than they wanted to come. They examined it, dug some superficial trenches, but found nothing of scientific interest. They told the contractor he could go on.” In 1970, the construction was completed and the Siebenbergs moved into their new house.

In Israel, news of archaeological discoveries makes headlines. Shortly after they moved into their new home, the Siebenbergs found themselves in the middle of the headlines, so to speak, for Hebrew University archaeologist Nachman Avigad was uncovering dramatic evidence of the history of the area around the couple’s home. Avigad found large quantities of pottery, pieces of floor tiles made from Italian marble, hairpins of bronze and ivory, cooking utensils and vessels, weights, grinding stones, tables, and the remains of buildings, towers, cisterns, baths and even a famous Byzantine church.

Theo and Miriam read and watched. Perhaps, the Siebenbergs speculated, the experts who had declared their house site archaeologically barren were wrong. Perhaps the experts had overlooked something.

Theo applied to the Department of Antiquities for a permit to excavate beneath his house. Although the Department’s experts were convinced that Siebenberg’s search would be fruitless, his infectious enthusiasm carried the day and the permit was issued.

It was a quixotic undertaking, especially because of the enormous engineering difficulties in excavating beneath an already existing house. Avigad was excavating under rubble. The Siebenbergs would have to dig under a four-story house sitting on a hillside.

Siebenberg’s architect and engineer were no more encouraging than the experts at the Department of Antiquities. Preventing the collapse of the house would require expert digging, shoring and support-building.

“At first they even said it couldn’t be done, it’s too late. I should have told them before I built the house,” recalls Theo. “But eventually they devised a system of excavating one section at a time, laying concrete piers, anchoring the piers with steel piles and going on to the next section.”

It took a year-and-a-half to create the first section of the retaining wall. The landfill removed to create the excavation was taken out in individual bags by laborers and sifted one by one in search of artifacts. That sequence—meticulous excavation interrupted by the need to build supports to keep the house from falling in—was the arduous pattern that was to characterize the next eight years.

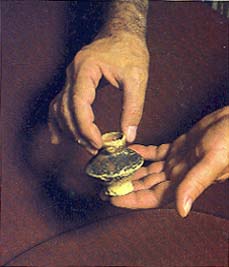

Toward the end of the second year, someone at last spotted the first find. It was a bronze key ring, of the kind worn in the Herodian era, that doubled as a key to a jewel box, not unlike the one found by Yigael Yadin in a cave near the Dead Sea.

048

Encouraged, the team pressed on under the single-minded supervision of Theo Siebenberg, who, by this time, had dropped everything to concentrate on his dig. The workers made other finds—a bronze bell, a rhyton, arrowheads, a half-burned gold pen and an ink well. They uncovered evidence of the Roman conflagration—a line of ash sealed into a stratum. They uncovered a ritual bath or mikveh which had been part of the house. And, some 30 feet down, the remnants of the base wall of the home that had stood there 2,000 years before.

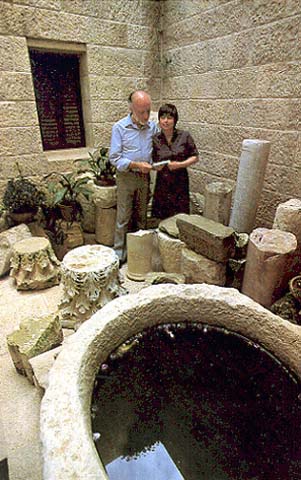

In an area just outside the Siebenbergs’ house line, they found a Byzantine water cistern. The cistern is itself four stories deep. It measures 25 by 38 feet. Most of the original pink plaster still lines the inside of the immense cistern. On one wall, just below the water line, are two Byzantine crosses, each enclosed in a circle. This cistern is almost too large to serve a single family. Perhaps at one stage there was a public building here.

Under the house, excavation had not yet reached bedrock. But before allowing Theo to go further, engineers argued for still more concrete supports. He relented, impatient at further delays. As they went further down, workers found tombs cut into the bedrock. The tombs were empty, but the discovery proved that at the time these tombs were carved, probably in the eighth century B.C., this area was still outside the city walls.

As the workers reached bedrock, another idea began to tease Theo Siebenberg. The engineers had insisted on maximum structural integrity. The space under the house was as sound and secure as a subway station. There were four levels of excavation, going down more than 60 feet. Why not use all that space. Why not create a museum?

Theo’s notion took shape with grandiose flourish. Architect Yaakov Ya’ar said, yes, it was feasible and immediately began to draw up the design. Siebenberg formed the Jerusalem Historical Institute, a public foundation whose board consists of prominent archaeologists and other leading citizens. The Institute would be both the vehicle for creation of the museum and the beneficiary of the Siebenberg findings and home after they died. (There are no children.)

Ya’ar’s design—bearing the very clear stamp of the ubiquitous sponsor—is a multi-level glass and stone complex linked by stairways and encompassing not only the underground space but also the adjacent Byzantine cistern, open to the sky.

“We’ll have the artifacts from the original mansion, plus audio-visuals,” says Theo, his calm manner only half concealing his excitement. “For example, we’ll have an original arrowhead, and with it a quotation from Josephus, and maybe some blow-up photographs depicting other findings elsewhere. I’ve put in 12,000 feet of electric conduits for audio-visual aids in five languages that people will be able to listen to with earphones. There will also be scale models of the area before the destruction and the major buildings that stood there—including the Temple Mount.”

“We’ll be using 350 of the original stones we’ve recovered to reconstruct a wall of the mansion. People will be able to walk through and actually get the feeling of what it was like to live in that house 2,000 years ago.”

These ideas are all emanating from this one diminutive man who, remarkably, possesses no technical background whatsoever for what he’s doing. Just vision and drive. And patience. The museum is ready to be built, but the city of Jerusalem is constructing a new drainage system and Theo must wait to plug his system into the larger one. Like most other bureaucratic efforts, this one is dragging. It may be a 049year and a half before the museum is a reality. Maybe more.

Meanwhile, Theo and Miriam must content themselves with reveries of what it will he like. One of the most pleasant musings involves a bronze bell uncovered near a Byzantine structure that was built with stones from the Hasmonean era. The bell dates to the Second Temple period and fascinates the Siebenbergs because it gives “the exact sound heard in this house so long ago.”

The bell prompted another idea for sharing finds with the public. The Byzantine cistern, now in effect a walled courtyard open to the sky, will be modified to become a music area, with circular stairs leading down to a platform. On the platform musicians will recreate the sounds of ancient music.

One can picture the Siebenbergs on a cool, starry Jerusalem night, sitting with the audience in their courtyard, listening to lyre, pipe and cymbal. Theo Siebenberg, eyes closed, perhaps remembering the days of his youth in Antwerp. But then the notes of ancient instruments catch on the breeze and fly across Jerusalem, across the stones of history.

“Pouring into the alleys [of the Upper City], sword in hand, they massacred indiscriminately all whom they met, and burnt the houses with all who had taken refuge within. … running everyone through who fell in their way, they choked the alleys with corpses and deluged the whole city with blood, insomuch that many of the fires were extinguished by the gory stream.”a Two thousand years later Theo Siebenberg stared in amazement at the perfectly formed skull that he knew must have belonged to a Jewish resident of the Upper City at the time of the bloodbath that climaxed […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username