“No actual remains of Solomonic Jerusalem have survived,” Dr. Kathleen Kenyon wrote shortly before her death in 1978.1 Most scholars would agree with famous British archaeologist even today.

I believe she is wrong. A major Solomonic monument is visible in Jerusalem today for all to see. Indeed, virtually every visitor to Jerusalem does see it, but, like the scholars, fails to recognize it for what it is.

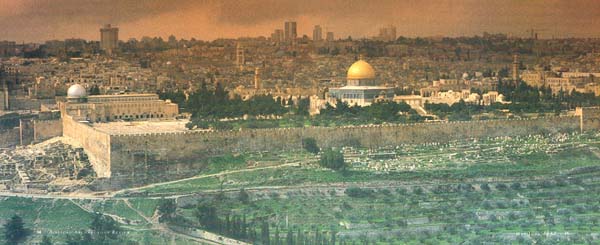

I believe part of the eastern wall of the Temple Mount is Solomonic construction.

All agree that in about 960 B.C. Solomon started to build his famous temple somewhere on the Temple Mount (see 1 Kings 5–7; 2 Chronicles 2–4), although there is considerable debate about just where it was located within this monumental enclosure.2 Nor is there any doubt that Solomon built a temple enclosure wall and filled it in to create a level surface or podium on which to build not only the Temple of Yahweh, but also his own palace.

In 587 B.C., the Babylonians led by Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Solomonic Temple.

When the exiled Judeans returned from Babylonia to Jerusalem in the late sixth century B.C., they rebuilt the destroyed temple (the Second Temple).

In the first century B.C., the Temple was substantially rebuilt by Herod the Great, so much so that scholars often refer to Herod’s Temple as the Third Temple, although in traditional theological Jewish terminology, he simply rebuilt the Second Temple. Herod’s temple was burned by the Romans when they destroyed Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

Although it was Solomon who first built the temple enclosure wall to create a podium on which to build the temple and his palace, much of the temple enclosure wall as it exists today is admittedly Herodian or later.a In many places, the distinctive Herodian masonry is easily recognizable. Even the oldest and lowest coursesb of part of the temple enclosure wall are Herodian, because Herod actually doubled the size of the old Solomonic Temple Mount. Herod did this by extending the Temple Mount area on the north, south and west. As a result, whatever may be left of the older, Solomonic temple enclosure walls on the north, south and west are now buried deeply within the Temple Mount.

But this is not true of the eastern temple enclosure wall. Herod could not extend the Temple Mount eastward because on the east Solomon had built it on the edge of a steep slope going down to the Kidron Valley. On the eastern side of the Temple Mount, Herod had to follow the line of the Solomonic wall, although he extended this wall southward and northward.

We know just how much Herod added at the southern end of the eastern Temple Mount enclosure wall. We know this because there is a famous “straight joint” in the eastern wall of the enclosure, 101 feet from the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount (see map). Normally, a masonry wall is built of interlocking masonry; the joints between stones alternate as one course is placed upon another. But near the end of the eastern enclosure wall, there is a straight vertical line of masonry. When Herod extended this eastern wall southward, he added 107 feet to the wall and thereby created a straight joint where the Herodian extension joined the existing wall; the bottoms of the Herodian courses join the courses to the north of the straight joint at the midpoint in their height.

This straight joint is easily visible today. It does not extend to the top of the eastern wall because later repairs replaced the masonry on both sides of the straight joint at the uppermost courses. But in the lowest ten courses, for a height of about 38 feet, the straight joint is plainly visible.

The oldest part of the eastern wall to the left (south) of the straight joint must be Herodian. The distinctive Herodian masonry in this southern extension confirms that the Herodian masonry has been preserved very nearly to the top of the wall.

But what about the masonry to the right (north) of the straight joint? I believe the exposed wall north of the straight joint was built by King Solomon in the tenth century B.C.c

Scholars have defended three principal views regarding the date of the masonry to the right of the straight joint: (1) It dates to the Hellenistic (332–63 B.C.) and, more particularly, the Hasmonean period (164–31 B.C.); (2) It dates to the Persian period (538–333 B.C.); and (3) The position which at the moment I alone defend, it dates to the Solomonic period (tenth century B.C.).

In assessing the validity of the various arguments, one must consider not only the likelihood that the temple enclosure wall at this point was destroyed at a particular time in history, but also that it was rebuilt at another particular time.

In short, if the enclosure wall is not Solomonic, the Solomonic wall that once existed here must have been destroyed. And it also must have been rebuilt—not an easy task.

Most scholars agree that King Solomon originally built the eastern temple enclosure wall more or less on the present line of the eastern wall of the Temple Mount. Solomon’s temple enclosure wall terminated at the straight joint, which marks the southeastern angle or corner of Solomon’s Temple Mount. Kathleen Kenyon herself suggested that excavation to the right of the straight joint down to bedrock “might reveal at the base Solomonic masonry.”3

If the exposed masonry to the right of the straight joint is not Solomonic, this part of the enclosure wall must have been destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 B.C. when they captured and burned Jerusalem.

How likely is it that the Babylonians, led by Nebuchadnezzar, destroyed the eastern retaining wall of the temple enclosure? We shall look at the Biblical references first, but these unfortunately provide only minimal assistance simply because they don’t give enough details about the magnitude of the destruction. According to 2 Kings 25:9–10 (substantially repeated in Jeremiah 52:13–14):

“He [Nebuchadnezzar] burned the House of the Lord, the king’s palace, and all the houses of Jerusalem; he burned down the house of every notable person. The entire Chaldean force that was with the chief of the guard tore down the walls of Jerusalem on every side.”

There is no indication, however, that Nebuchadnezzar tore down the retaining wall of the temple platform. To have done so would have required enormous effort and gained him little, if anything.

It is worth remembering that Nebuchadnezzar did not have at his disposal the destructive capability of a modern army. Instead of modern-day weapons, Nebuchadnezzar had to rely on battering rams, tunnels dug under walls to undermine them, and fire. None of this would have been very effective on the eastern wall of the Temple Mount, which was built on top of a steep slope leading down to the Kidron Valley. A battering ram could not climb the steep slope outside the eastern temple enclosure wall. Fire would not destroy the stones. As Louis-Hugues Vincent and A. M. Steve have written:4

“Don’t suppose that the Babylonians razed to their foundations the walls of the Holy City. Without doubt they employed their battering rams and their undermining walls to make multiple breaches; the crenellations [on the top of the walls] had been carefully demolished and all the gates burned, in order to leave gaping the dismantled openings; but for a more or less considerable length of time afterwards, particularly in the spots judged to be of secondary importance, the old rampart was able to again play a role and required only small repairs to become useful.”

If this was true of the freestanding walls of the city, how much more true was it of the temple enclosure wall that served as a retaining wall for the podium?

There was no military reason for Nebuchadnezzar to attempt to destroy the temple enclosure wall. His attack, as is almost always the case when Jerusalem is attacked, came from the north. The east, with its steep slope up the Kidron Valley, is the least likely place for an attack. Its defenses are largely irrelevant, compared to its natural defenses.

Moreover, as I have noted, the eastern temple enclosure wall was in its lower part—and that is the part we are talking about—a retaining wall as well as a defense wall. Nebuchadnezzar may well have destroyed the freestanding wall that surrounded Solomon’s Temple and palace, built around the edge of the platform or podium, but the wall of the platform itself is another matter. Had Nebuchadnezzar pulled down the eastern enclosure wall, the huge temple platform would have collapsed. Even Herod the Great, the most impressive builder of all time in the Holy Land, when he rebuilt the Second Temple and doubled the size of the Temple Mount, nevertheless incorporated the existing eastern wall of the temple enclosure. He did not rebuild it.

It is interesting that although Jerusalem has been captured and destroyed numerous times in the last 2,500 years, none of its conquerors has succeeded in destroying the Temple Mount enclosure to a level lower than the surface of the podium inside. Nebuchadnezzar was no exception.d

Perhaps the most telling argument as to why Nebuchadnezzar did not destroy the temple enclosure wall is that if it had been destroyed, the returning exiles would never have been able to build the Second Temple. As I previously noted, had Nebuchadnezzar pulled down the eastern enclosure wall, the huge temple platform would have collapsed.

In general, the Biblical passages dealing with the construction of the Second Temple emphasize its mediocrity in comparison to the earlier Temple built by King Solomon.

More specifically, in 538 B.C., Cyrus, king of Persia and heir to the Babylonian empire, published a decree allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem and to rebuild their temple. The Book of Ezrae identifies the individual who led the first returning exiles back to Jerusalem armed with Cyrus’s decree as one Sheshbazzar (Ezra 1:8, 11, 5:14), who is described as the leader, or governor, of Judah.f According to Ezra 5:16, Sheshbazzar laid the “foundations” of the Temple after his arrival in Jerusalem. Nothing is said of the enclosure wall and there is no reason to suppose that it was rebuilt by Sheshbazzar.

Whatever Sheshbazzar accomplished, it was apparently so insignificant that it received not even a passing mention in the other books of the Bible—Haggaig and Zechariahh—that relate the story of the rebuilding of the Temple. Twenty years after the return from the Exile, the prophets Haggai and Zechariah were still exhorting the people to show some initiative and get to work on the Temple, which still lay in ruins (Haggai 1:4, 9, 2:1–9; Zechariah 1:16, 6:12–13, 8:9). It is therefore unlikely that Sheshbazzar did anything more than clear away some of the debris;5 he certainly could not have been responsible for a major reconstruction of the Temple Mount enclosure wall.

Zechariah gives credit to Zerubbabel for laying the foundation of the Temple (Zechariah 4:8–10; see also 8:9). Zerubbabel started work in 520 B.C. The Second Temple was completed and ready for dedication by 515 B.C. It would have been impossible for Zerubbabel to have embanked a temple platform, built the eastern retaining wall to support that platform, and constructed the Temple, all in five years. The only way Zerubbabel could have completed the Second Temple in so short a time span would be if he was able to rely on a substantial amount of existing groundwork, including the temple platform and its eastern retaining wall.

Consider that to embank the platform, to build the enclosure wall and to erect the Temple and palace, Solomon, even at the height of the Jewish state’s prosperity, was forced to corvée 150,000 to 200,000 men starting in about 960 B.C.; and the work still wasn’t completed at Solomon’s death, in 931 B.C., 30 years later. Is it reasonable to suppose that upon their return from exile a few impoverished refugees were able to accomplish in just a few years what Solomon during the Golden Age of Judah—when money was as plentiful as rocks, according to the Bible (1 Kings 10:27)—couldn’t finish in 30 years?

The more likely conclusion is that the returning exiles simply built the new Temple upon the existing foundations, on the old temple platform, which Nebuchadnezzar had not bothered to destroy.i

None of the scholars who in recent years have argued for a later date for this wall north of the straight joint have confronted this obvious historical data, perhaps because they are not professional historians. But this evidence must be considered by anyone who argues for a later date for this wall.

Let us turn now to the archaeological evidence.

The straight joint was first noticed by the British surveyor and engineer Charles Warren in 1870. At the time he observed it, only two courses (H and I on Warren’s plan) were exposed to the right of the straight joint. In addition, Warren explored three more courses (W, X and Y) underground. In 1965, the Jordanian Department of Antiquities excavated eight additional courses of this wall to the right of the straight joint. Now ten courses are exposed. As you will recall, Kathleen Kenyon suggested that at the base of this wall we might find Solomonic masonry. But the condition of the presently exposed wall above ground suggests that this is the same masonry we will find at the base. There is no indication that this part of the wall is a repair. At the level of courses H to Q (exposed since 1965) and at the level of courses W and X on Warren’s plan, all the courses to the right of the straight joint join the courses to the left of the straight joint at the midpoint in their height. Moreover, the ashlars to the right of the straight joint are remarkably uniform in height.6 That so many more courses exposed in 1965 are identical to the five courses observed by Warren indicates that all of this part of the wall, down to bedrock, was built at one time as part of the same wall.

The case for dating this part of the temple enclosure wall to the Persian period is based largely on archaeological argument. It has been made by the distinguished French archaeologist Maurice Dunand. In 1968, Dunand delivered a paper at the Sixth Congress of the International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament in which he contended that the masonry to the right of the straight joint must be dated to the Persian period (Sheshbazzar, 538–520 B.C.).7 Dunand based his argument primarily on the similarity of the masonry to Persian period masonry at the Phoenician sites of Byblos and Sidon in Lebanon. Moreover, the masonry to which Dunand compared the Jerusalem masonry at these Phoenician sites was found in the walls of podiums of Phoenician temples, just as in Jerusalem. Not only was the design of the ashlars the same, but the height of the courses at the base of the exposed part of the Jerusalem wall is 45 inches, precisely the same as the height of the courses in the Eshmun temple in Byblos.j

The Phoenician-style temple at Sidon dates to the end of the sixth century; the Byblos temple is a little later. Dunand concluded that the Achaemenidsk had constructed the temple podium walls in Byblos, Sidon and Jerusalem at roughly the same time and for the same purpose—to create a platform on which to build a temple.

The Persian ruler Cyrus had conquered Babylon in 539 B.C., putting an end to Babylonian hegemony over Judea. Although he thereby managed to neutralize one main threat to his rule, the Babylonians, Cyrus still had the Egyptians to contend with. To guard against Egyptian infiltration into the western edges of this empire (Syro-Palestine, traditionally an area coveted by the Egyptians), Cyrus and his successors tried to put both gods and men to work. According to Dunand, the Achaemenids relied not only on military fortifications to protect their fiefdom, they appealed as well to as many different gods as they could. This explains why they used their own resources to build a temple to the goddess of Byblos and a temple to Eshmun in Sidon and similarly in the case of the temple to Yahweh in Jerusalem. These gods would be enlisted in the fight against Egypt, and their followers would be so grateful to the Persians that they would give up any thought of revolting and siding with the Egyptians.

Dunand convinced several scholars of his position, including Kathleen Kenyon. In 1971, she wrote:8

“M. Maurice Dunand, well versed in the masonry of Phoenicia, expressed an opinion on visiting the site that the visible masonry north of the straight joint is Persian. This he very convincingly demonstrated to me in a visit to the great Temple of the Eshmun, near Sidon, dated to the late sixth–early fifth century B.C., and to the rather later structures of the Persian period at Byblos. It is thus very tempting to ascribe it to the work of Zerubbabel, who, when the first exiles returned to Jerusalem under the Persian aegis, restored the Temple, completing the restoration circa 515 B.C. (Ezra 6:15).”

Dunand is in some respects correct. He simply did not go far enough. He properly recognized the similarities between the Phoenician masonry at Byblos and Sidon, on the one hand, and the Phoenician influenced masonry at Jerusalem. He failed, however, to consider whether this Phoenician-style masonry could go back even further.

At this point, it behooves us to look more closely at the masonry to the right of the straight joint. The blocks of stone used in the bottom 11 courses to the right of the straight joint clearly differ from the Herodian masonry to the left of the joint. The Herodian blocks to the left of the straight joint have a flat, smooth, slightly raised surface in the middle (called a boss), surrounded on all four sides by flat, smooth, depressed borders about three to four inches wide (called marginal drafts or margins). By contrast, the center bosses on the ashlars to the right of the straight joint bulge; they’re rounded; they’re lumpy; they’re irregular; the rock of the bosses is unpolished; the bosses protrude much more than the bosses to the left of the straight joint; the margins to the right of the straight joint are not as precisely defined.

It is Dunand’s contribution to note that bosses and margins like these can be found before the Hellenistic period. There are still those who reject this position, as we shall see; the naysayers admit that there is earlier masonry with a boss like that on the masonry to the right of the straight joint, but not with margins on all four sides, they say.

My examination of numerous sites throughout Syria-Palestine has shown me examples of such masonry—with similar bosses and margins on all four sides—not only from Byblos and Sidon but from structures dating much earlier.

In her excavations in the City of David, the oldest inhabited part of Jerusalem, Kathleen Kenyon herself found an ashlar with a bulging, rounded boss and four margins. She herself dated it to pre-Exilic times (pre-587 B.C., when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and the Exile began).

At Tel Dan, Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran uncovered a large bamah, or high place, from the period of the Divided Kingdom (c. 931–721 B.C.). At that time, Dan was a northern rival of the sanctuary in Jerusalem. Some of the ashlars in the structure of the bamah (which the excavator attributes to King Ahab, 874–853 B.C.) are similar to the ashlars to the right of the straight joint in Jerusalem, with rounded bosses and margins on four sides.9

From an even earlier period, masonry like this was excavated at Megiddo, which the Bible itself tells us was one of the cities Solomon built (1 Kings 9:15).10

It is interesting that Phoenician influence can be traced at all of these sites. King Ahab, the builder of the bamah at Dan according to the excavator, was married to Jezebel, the Phoenician daughter of the king of Tyre and Sidon (see 1 Kings 16:31). The Phoenician influence on Solomon’s Temple is even more explicit in the Bible. The relations between Solomon and Hiram of Tyre were close and extensive. Hiram supplied the Cedars of Lebanon for Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 5:8), and he supplied Solomon with masons (1 Kings 5:18). Hiram also executed the metal work (1 Kings 7:13) and made some furnishings for the Temple (1 Kings 7:40). The layout and design of Solomon’s Temple were based on contemporaneous Phoenician models.

It is likely that Phoenician masons were also the foremen who supervised the construction of the bamah at Dan, in the time of Jezebel. Here the ashlars, although similar in design, are, as we would expect, smaller than those used at the royal center in Jerusalem. Jerusalem was plainly more important.l

Masonry in the Phoenician style, which we have seen at Jerusalem north of the straight joint, as well as at Byblos, Sidon, Dan and Megiddo, can be traced back as early as the 14th century B.C. at Ugarit, on the northern Syrian coast, which was under strong Phoenician influence. This style of masonry was found there by Professor Claude F. A. Schaeffer in his excavation of the Royal Palace of Ugarit.11

As is well known among archaeologists, it is extremely difficult to date masonry by its style. I agree. I have certainly not proven on the basis of these archaeological comparisons that the masonry north of the straight joint in Jerusalem is Solomonic. All that I have shown is that it could be. On the basis of the masonry alone, it could be from any period from the 14th century B.C. on. The important point is that an early attribution cannot be excluded by the style of masonry.

To date the wall north of the straight joint more precisely, we must turn to history, not archaeology. And history tells us that this wall was most likely constructed by King Solomon to support the podium on which he built the Temple of Yahweh and his own palace.

The principal recent attack on my position comes from Israeli archaeologist Yoram Tsafrir. Tsafrir contends that the masonry right of the straight joint is Hellenistic (more particularly Hasmonean: 164–37 B.C.).

Tsafrir has excavated a Hasmonean fort known as Sartaba or Alexandrium, overlooking the Jordan Valley. There he has found a wall that he claims closely resembles the wall to the right of the straight joint.12 But, as I have noted, it is notoriously difficult, all agree, to date a wall by masonry alone—and this is what Tsafrir does when he dates the Jerusalem wall by comparison with the wall at Sartaba. On the basis of the wall at Sartaba, the Jerusalem wall could be Hasmonean, but it could also be much earlier.

Tsafrir claims that no earlier masonry had four margins. He claims that the earlier masonry with a bulging, rounded boss had fewer than four margins—usually two or three, with the boss extending out to the end of the ashlar on the side or sides without a margin. Sometimes this does occur, but sometimes it does not.13

Moreover, Tsafrir is forced to reject not only my dating of the wall north of the straight joint, but also that of Dunand (and Kenyon, who accepted the similarity of masonry style pointed out by Dunand). Dunand and Kenyon are acknowledged archaeological experts with years of field experience. Yet Tsafrir must argue that their masonry comparisons are also wrong.

According to Tsafrir, the Seleucids in the mid-second century B.C. built, in the area of the straight joint, their famous fortress known as the Akra. The wall north of the straight joint is, according to Tsafrir, part of the Akra. The location of the Akra is much debated. Tsafrir alone places it at the southeast corner of the Temple Mount. Without going into detail, I find this location most unlikely. This area is considerably below the summit of the hill to the north and would seem a poor place, from a military viewpoint, for a fortress. Even on an east-west axis, there is higher ground to the west that would be a much better location.

But even if the Akra was located here, that does not necessarily mean that this wall was rebuilt by the Seleucids as part of their fortress. There was no reason why the Seleucid builders could not have used the earlier wall already in place as part of their fortress. This would certainly have saved money.

Perhaps the most telling argument against the reconstruction of this wall by the Seleucids is the historical one. This wall is basically a retaining wall. It is easy to build the first time, for when it was originally built it was freestanding. After it was built, Solomon poured fill inside to create a level podium on which to build the Temple and his palace. At that point, it became a retaining wall. It would then be an enormous job to tear it down—or to rebuild it. Certainly such a task would be beyond the capability of the impoverished exiles who returned to build the Second Temple. Even Herod the Great, when he doubled the size of the Temple Mount, did not tear down and rebuild this wall. If he had tried, the fill behind the wall would have collapsed and could have been replaced only with the greatest difficulty. Who then does Tsafrir suggest performed such a thankless, useless task?

It is true that our literary sources—Josephus and 1 Maccabees—state that Judas Maccabee, the Hasmonean, reconstructed the defense wall that surrounded the Temple Mount.14 But this refers to the upper, freestanding part of the wall, not the lower part of the enclosure wall that served as a retaining wall. There is no indication that Judas Maccabee reconstructed the lower part of the wall that served as a retaining wall. Indeed, the implication is to the contrary, because if the lower part of the wall had previously been demolished, the podium itself would have collapsed to a considerable extent and there would have been no way to reconstruct the upper part of the wall—the part that was freestanding and that served a purely defensive purpose.

True, the lower part of the wall could have been repaired through the ages—precisely because no one would want to rebuild it from scratch. But, as I have noted, there is no sign of a repair or a rebuild in the ten courses exposed to the right of the straight joint. Indeed, when the Jordanian Department of Antiquities exposed the eight additional courses in 1965, these courses beautifully matched the already exposed two courses, suggesting that this is what the wall looks like all the way down to its foundation.

Tsafrir makes one final argument: On the masonry north of the straight joint can be seen traces of a combed chisel (shahouta). Also known as a dentate scraper, a scraper with teeth, this instrument was used to decorate masonry in ancient times, and it is used again now. It leaves a series of lines (impressed by the teeth of the comb) when it is drawn across the masonry. The question is whether the traces of these lines on the masonry north of the straight joint can be used to date it.

Tsafrir argues that the dentate scraper was not used before the Hellenistic period and therefore masonry with these comb marks on it cannot be earlier than the Hellenistic period. There are several reasons why this argument will not hold:

First, it is by no means clear that the dentate scraper was not used earlier. This matter was the subject of a heated debate between two Israeli archaeological giants, Yigael Yadin and Yohanan Aharoni, both now unfortunately deceased. Yadin argued that the dentate scraper was “typical of Hellenistic and Early-Roman stone-dressing.”15 Aharoni replied by producing numerous instances where the dentate scraper was in evidence on Iron Age (c. 1200–600 B.C.) masonry.16 That more examples have not survived is no doubt due to erosion.

But even if the dentate scraper was not used as early as Solomon’s time, this would not answer our question. Insofar as there are traces of the use of a dentate scraper north of the straight joint, there are similar traces south of the straight joint. It may well be that Herod the Great, at the time he enlarged the Temple Mount, redressed the earlier masonry. By applying a dentate scraper to the masonry on both sides of the straight joint, the new masonry he added south of the straight joint would more nearly match the old masonry north of the straight joint.

Thus, I conclude that the ten exposed courses of masonry at the base of the temple enclosure wall north of the straight joint were probably part of the wall constructed by King Solomon to create a podium on which to build the Temple of Yahweh and Solomon’s own royal palace. It is there in Jerusalem for all to see.

This article was translated and adapted from the French, and approved by the author.

For further details see E.-M. Laperrousaz: “Quelques résultats récents des fouilles archéologiques conduites a Jérusalem et aux alentours de la Ville Sainte,” Revue des Études juives (REJ) 129 (1970), fasc. 2–4 (April–December); “Quelques apercus sur les dernières découvertes archéologique faites à Jérusalem et aux alentours de la Ville Sainte, REJ 131 (1972), fasc. 3–4 July–December); “A-t-on dégagé l’angle sud-est du ‘Temple de Salomon’?” Syria 50 (1973), fasc. 3–4; “Remarques sur les pierres à bossage préhérodiennes de Palestine,” Syria 51 (1974), fasc. 1–2, “Angle sud-est du ‘Temple de Salomon’ ou vestiges de l’ ‘Acre des Séleucides’ Un faux problème,” Syria 52 (1975), fasc. 3–4; “Encore l’ ‘Acre des Séleucides’ et nouvelles remarques sur les pierres à bossage préhérodiennes de Palestine,” Syria 56 (1979), fasc. 1–2; “Après le ‘Temple de Salomon’ la Bamah de Tel Dan: I’utilisation de pierres à bossage phénicien dans la Palestine préexilique,” Syria 59 (1982), fasc. 34, “A propos des murs d’enceinte antiques de la Colline occidentale et du Temple de Jerusalem (bref bilan de dix Missions archéologique: 1970–1980),” REJ 141 (1982), fasc. 3–4 July–December).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Since Herod’s time, the temple enclosure wall has been repaired by successive conquerors—Arabs, Crusaders, Ottoman Turks, and most recently by Jordanians, who added, for instance, the highest courses of the famous Western or Wailing Wall where Jews have come for centuries to mourn the loss of their Temple.

Note how much of the Temple enclosure walls survived the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., despite the power and technology available to the Romans when they devastated the city. Why, then, should we suppose the Babylonians totally destroyed the eastern wall in 586 B.C.?

Ezra and Chronicles were likely written by the same author, and the Chronicler probably wrote around 350 B.C. (For discussion of the authorship of Ezra and Chronicles, see Menahem Haran, “Explaining the Identical Lines at the End of Chronicles and the Beginning of Ezra,” Bible Review, Fall 1986, and Hugh G. M. Williamson, “Did the Author of Chronicles Also Write the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah?” Bible Review, Spring 1987.)

In Ezra 3:10–12 we are also told that Sheshbazzar laid the Temple’s foundations. The historical accuracy of this material has been seriously questioned by Frank Michaeli in his Les Livres des Chroniques, d’Esdras et de Nehemie, Commentaire de l’Ancien Testament, No. 16 (Neuchatel and Paris, 1967) pp. 265, 268. But in any event, the passage refers to the foundations of the Temple, not the temple platform or podium. Sheshbazzar was perhaps the son of Jehoiachim (cf. 1 Chronicles 3:18), the penultimate king of Judah, who ruled from 598 to 597 B.C.

The prophecies of Haggai date to the early years of the reign of Darius I (the third Achaemenid), to about 520 B.C., 18 to 20 years after the edict of Cyrus II.

Zechariah was a head of one of the priestly families that returned to Jerusalem with Zerubbabel (see Nehemiah 12:16). He prophesied from 520 to 518 B.C.

It is also worth observing that Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, ascribes the building of the eastern temple enclosure wall to Solomon or his direct, pre-Exilic descendants; The Jewish Wars (V, V, 1, 184–189), as well as Antiquities of the Jews (VIII, III, 9, secs. 95–98; XV, XI, 3, secs. 397–402; XX, IX, 7, sec. 221).

Dunand also noted some differences that he regarded as insignificant: The size of the ashlars differs somewhat in other dimensions and the stone is different.

The rulers of the Persian empire were known as Achaemenids after Achaemenes, an ancestor of Cyrus II.

Even Herod the Great, in his huge building projects in first-century B.C. Palestine, used widely differing sizes of ashlars. For example, at Samaria, in the western part of his defense wall, he used ashlars that are generally about one-half the size of the stones he used in Jerusalem; moreover, at Samaria the width of the margins and especially the thickness of the boss are relatively greater than at Jerusalem (cf. Laperrousaz, Syria 50 [1973], p. 388). So we should not conclude that because of differences in the size of ashlars or margins that the masonry is not contemporaneous.

Endnotes

Kathleen Kenyon, The Bible and Recent Archaeology (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), p. 52. See also Kenyon, Royal Cities of the Old Testament (Covent Garden: Berrie and Jenkins, 1971), p. 46: “Not a trace has survived of Solomon’s Jerusalem.”

Asher S. Kaufman, “Where the Ancient Temple of Jerusaiem Stood,” BAR 09:02.

Louis-Hugues Vincent and A. M. Steve, Jerusalem de l’Ancien Testament. … (Paris: J. Gabalda, 1954–56), First part, p. 241.

See André Parrot, Le Temple de Jerusalem, Cahiers d’archeologie biblique, no. 5; 1st ed. (1954), p. 52, 2nd ed. (1962), pp. 54–55. W. Stewart McCullough, The History and Literature of the Palestinian Jews from Cyrus to Herod (Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1975), p. 25.

Maurice Dunand, “Byblos, Sidon, Jérusalem. Monuments apparentés des temps achéménides,” in Congress Volume, Rome 1968, Vetus Testamentum Supplement 17 (Leiden: Brill, 1969), pp. 64–70.

About the masonry: of Megiddo, cf. Laperrousaz, Syria 50 (1973), figure on pp. 396–397; of Tel Dan, Syria 56 (1979), figures on pp 112, 122 and Syria 59 (1982), figure on p. 233.

See Claude F. A. Schaeffer, “Fouilles et decouvertes des XVIIe et XIXe campagnes, 1954–1955,” Ugantica IV. Mission de Ras Shamra, Vol. XV. Institut Francis d’Archaeologie de Beyrouth. Bibliotheque archeologique et historique, Vol. LXXIV (Paris, 1962), XIII, cf. p. 107.

Yoram Tsafrir, “The Desert Forts of Judea in Second Temple Times,” Qadmoniot Vol. VIII, Nos. 2–3 (30–31), 1975.

Yigael Yadin implicitly recognized that Iron Age masonry sometimes had four margins and explicitly noted that the number of marginal drafts was not the “essential” difference between Iron Age masonry and later masonry. Yadin, “A Note on the Stratigraphy of Arad,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ), 15 (1965), p. 80.

Cf. 1 Maccabees 4:36–38, 41–43, 47–53, 55–57, 60–61; Josephus Antiquities XII, VII, 6, secs. 317–319; XII, VII, 7, secs. 323–324 and 326, Jewish Wars I, I, 4, sec. 39.

On this basis, Yadin argued that the Israelite fortress that Aharoni excavated at Arad, and which he dated to the Iron Age, was in fact Hellenistic. Yadin, “A Note on the Stratigraphy of Arad,” IEJ 15 (1965).