I think we have found Modi’in—not for sure, but very probably.

Modi’in is famous as the home of the Maccabee family—Mattathias and his five sons, who led the Jewish revolt against Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid ruler of Judea, in the 160s B.C.E. When Antiochus desecrated the Temple and forbade circumcision and Sabbath observance, the Maccabees led a successful revolt. Their victory is still celebrated in the annual Jewish festival of Hanukkah.

The most imposing monument in their little town of Modi’in was the tomb of the Maccabees with its seven pyramids—two for the mother and father and one for each of their five sons.a The first-century Jewish historian Josephus describes the tomb as “a very large monument” of “polished white stone” that “soared to a great height” and could be seen “for a long way off.”1 But not a stone of this monument has yet been found.

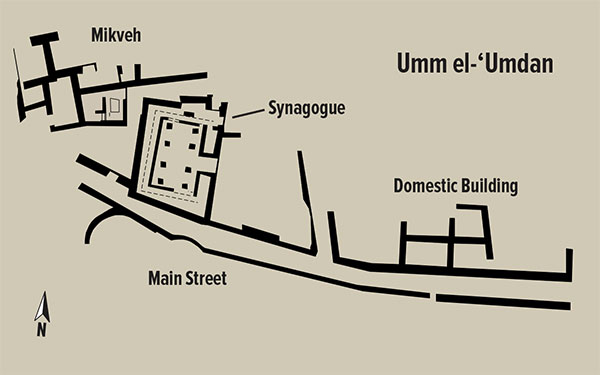

The site we identify as probably Modi’in has long been known as an archaeological ruin. In Arabic it is called Umm el-‘Umdan. It was surveyed and described by the great French scholar, archaeologist, explorer and diplomat Charles Clermont-Ganneau in 1873–1874.2 He mentions the remains of several ashlar buildings, one of which he identified as a church with columns, some complete and some fragmentary, that lent the Arabic name to the ruin, i.e., Umm el-‘Umdan, “Mother of the Columns.” The site was also investigated by a British survey, and the findings were published in 1883.3 But the British survey mentions no columns. By that time they were probably reused in other structures or looted.

When a modern road was planned near Umm el-‘Umdan, an excavation was required by Israeli law. The Israel Antiquities Authority undertakes such excavations, and the authors of this article were assigned to the task. Unfortunately, the head-director of the excavation and my colleague, Alexander Onn, died in August 2012 before the final report of the excavation had been published (it had been submitted and will be published in the IAA Reports Series). As the following article relies on our conclusions, I am honored to submit it on behalf of both of us.

Umm el-‘Umdan is located within the modern Israeli city of Modi’in, which lies about 20 miles northwest of Jerusalem, and was named to commemorate the ancient village of the Maccabees.

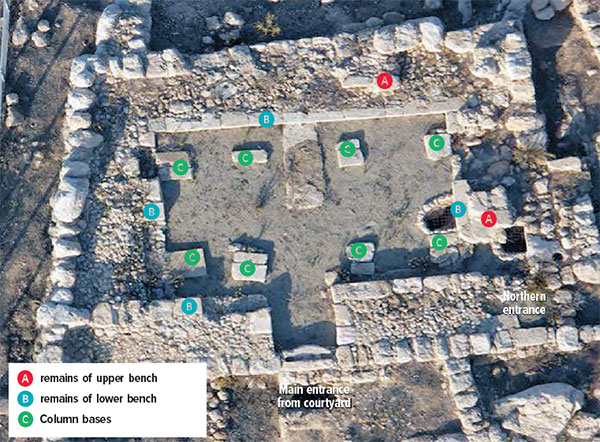

The first question is whether Umm el-‘Umdan can be identified as a Jewish village at the time of the Maccabean revolt. The site covers an area of a little more than 5 acres. The most prominent feature is a hitherto unknown synagogue dating to the time when the Second Temple still stood in Jerusalem—before the Roman destruction of 70 C.E. This synagogue was probably built during the reign of King Herod. With some alterations, during the first century C.E. it continued in use until the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, the so-called Bar-Kokhba Revolt, in 132–135 C.E. The main hall of the synagogue measured about 32 by almost 40 feet. The ceiling was supported by eight columns divided into two rows of four columns each. Only the stone-slab bases of the columns incorporated into the floor of the building have survived. We assume that circular-sectioned columns originally stood on these bases. With eight columns rather than the six of the other known synagogues from the Second Temple period (such as at Masada, Herodium, Gamla and Kiryat Sefer), the Umm el-‘Umdan synagogue is unique. Was it because of the lack of experience of the synagogue’s rural builders or because the columns supported an upper floor in this synagogue and were thought necessary to ensure the building’s stability, “just in case”?

The synagogue had a white chalk floor that was later slightly raised and coated with a thick layer of gray plaster. Stepped benches were built along the inner face of all four walls (except for the building’s main entrance). They usually survived only to the level of the lower bench (10 inches high and 10 inches wide), but in some places, remains of an upper second bench (10 inches high, unknown width) also survived. As the overall width of the structure of benches around the hall measures about 5.5 feet, we suggest reconstructing it as composed of two or three benches (i.e., a lower bench a foot wide and an upper bench 4.5 feet wide, or a lower bench a foot wide plus two upper benches each 2.3 feet wide).

A Jewish ritual bath, or mikveh, was exposed west of the synagogue. Steps built around a central pillar allowed the bathers to descend from the entrance level to the immersion pool. The bath consisted of two hewn rooms coated with gray hydraulic plaster that were separated by a passageway. The western room was covered with a vault, supported by the central pillar. Its rock-hewn floor consisted of two stepped levels. A hewn corridor with an arched ceiling led from the western room to the eastern room, which was at a lower level. Five steps descended to the bottom of this room.

The synagogue and associated mikveh seem clearly to identify Umm el-‘Umdan as a Jewish village in the late Second Temple period. But what about earlier—at the time of the Maccabean revolt? This synagogue and mikveh were constructed at least a century after the Maccabean revolt. Underneath the synagogue, however, we found the remains of a slightly smaller building that we also identify as a synagogue—from the Hasmonean period—constructed toward the end of the second or beginning of the first century B.C.E. The exterior northern, western and southern walls of this Hasmonean structure were built directly below the walls of the Herodian-period synagogue above and, like the later building, had benches (along only three walls, however, and not exactly parallel to the walls). The structure was enclosed with a courtyard on three sides, including where the mikveh would be built in a later period.

The floor of this synagogue was composed of small and medium-sized stone slabs, placed one next to the other. Two installations were incorporated into this floor along the hall’s central axis: The northern one was a square platform about 4 inches above the floor and a little over 3 feet on each side. The platform was paved with medium and large field stones whose upper faces were left coarse. The southern installation (of which we only found the outline of the robbery pit) was round, about 3 feet in diameter. These installations were presumably for the ritual reading of the Torah (the scroll of the Pentateuch). The entrance to the building faced east, toward Jerusalem.

The plan of the building and the quality of its construction attest to its use as a public building and identify it, like the later building, as a synagogue. Especially intriguing were fragments of red, white, yellow and green wall paintings that once decorated the walls of the building.4

Whether this building was here during the Maccabean revolt is not certain. If it wasn’t, the timing was very close. Beneath this structure, however, was still another structure that surely existed as early as the Maccabean revolt. It is securely dated to the Early Hellenistic period, during the reign of the Seleucids (the end of the third or beginning of the second century B.C.E.). Its plan differs slightly from the later buildings above it, but many of its walls continued to be used in the later buildings. It consisted of a rectangular hall nearly 23 feet long and 12 feet wide with a gray plastered floor. East of the building was an open courtyard. The role of this earliest Seleucid-period building is not known for certain.

Considering the fact that the Seleucid-period building lay beneath the two later synagogues and its walls determined the location and shape of the later buildings, we assume that it was a public building too. But we do not assume it was a synagogue. We know nothing about the nature of the settlement and its inhabitants in the late third–early second centuries B.C.E.

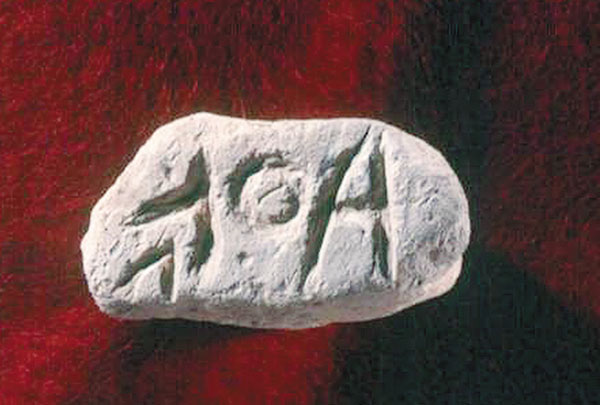

Much additional evidence, however, confirms that Umm el-‘Umdan was a Jewish village. Two stone seals, for example, were discovered near the ritual bath. One is a square seal ring engraved with a floral decoration of leaves and grapes. The other seal was made from a broken handle of a measuring cup and bears a four-letter inscription in the Aramaic language using square Jewish script. It was deciphered by the late Professor Joseph Naveh and reads

A network of winding and crisscrossing alleys that conforms to the topography of the village continued beyond the limits of the settlement and led to the agricultural fields beyond the inhabited area. Outside the settlement, we found many agricultural installations, such as winepresses, columbaria (dovecotes), terraces and dams, all attesting to the cultivation of the fields around the site.

Fragments of stone vessels also tend to confirm Umm el-‘Umdan’s identification as a Jewish village. Under Jewish law, stone vessels are immune from impurity. For this reason, stone vessels are very common at Jewish sites from the Second Temple period, from the time of Herod until the Bar-Kokhba revolt.

Another indication that Umm el-‘Umdan was a Jewish village is the almost complete lack of any luxurious or imported pottery. Only one imported Roman lamp was discovered. This is typical of Jewish sites around Jerusalem in the Hasmonean and Early Roman periods, such as at Herodium5 and Jericho.6

The burial complexes around Umm el-‘Umdan also indicate the site was a Jewish village. The tombs are bedrock-hewn and mostly have hewn forecourts in front of the burial caves. Two stages of burials were identified: primary burial in burial niches; and secondary burials, where the bones were gathered into ossuaries, or bone repositories—typical Jewish burials of the time. The fact that no burial complexes of this type were discovered inside the boundaries of the settlement reinforces the Jewish identity of the site’s residents: Jewish law dictates that their dead could not be buried within the limits of the settlement.7

Finally, coins found close to the synagogue from both the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.) and the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 C.E.) seem to confirm that Umm el-‘Umdan was a Jewish village. The coin from the First Jewish Revolt is inscribed “Year 2 of the Freedom of Zion.” The coin from the Second Jewish Revolt is inscribed “Year 2 of the Freedom of Israel.”

It thus seems clear that Umm el-‘Umdan was a Jewish village in ancient times. But was it Modi’in?

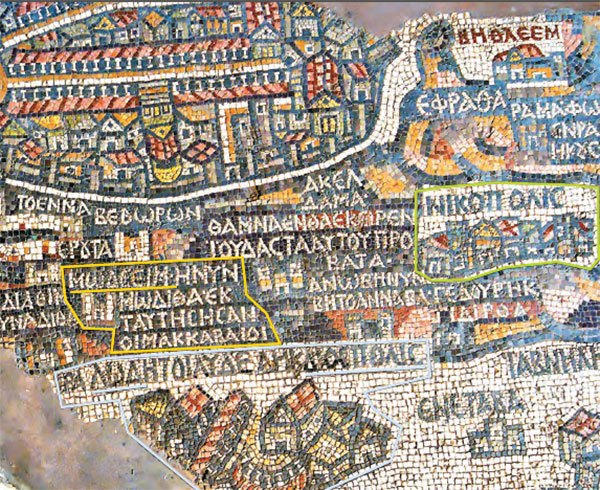

Hasmonean Modi’in is mentioned in ancient historical sources as a village (Josephus, Eusebius).8 On the Madaba Map, “Modi’in” is named in a drawing of a gate between two towers symbolizing a village.9 From the historical sources we know that the village was apparently founded before Mattathias moved there c. 170 B.C.E. Modi’in continued to exist in the Byzantine period, as indicated in the Onomasticon of Eusebius that was compiled at the beginning of the fourth century C.E. and on the Madaba Map, dated to the second half of the sixth century C.E. The village of Modi’in was probably abandoned before the Crusader period, because Crusader pilgrims in the 12th century identified the site of Modi’in elsewhere (next to Emmaus, in Tzuba, etc.).10

On the Madaba Map the village of Modi’in is located next to Lydda,11 between the mountains on which Jerusalem is located and the foothills to the west (the Shephelah),12 which is about 15 miles from Jerusalem. The Babylonian Talmud also identifies Modi’in as almost 15 miles from Jerusalem.13

Umm el-‘Umdan conforms to this location. It is located in the northern part of the Judean Shephelah, near the geographical border between the foothills and the Judean hill country, at an elevation of 750–820 feet above sea level. Three imperial Roman roads marked with milestones pass near the ruin at distances of 1–3 miles.14 Umm el-‘Umdan is situated about 650 yards south of the local Roman road leading from Lod (Lydda) via Barfilia, Bet Likia and Bido toward Jerusalem.15 The distance from Umm el-‘Umdan to Jerusalem by way of the internal Roman road is about 18 miles.

Modi’in is recorded on the Madaba Map in the center of a triangular area, with Jerusalem to the east, Nicopolis (Emmaus) to the south and Lod-Diospolis to the west. It fits the location of Umm el-‘Umdan. It is surrounded (on the Madaba mosaic) by a chain of villages, most of which are identified with sites located around the site of Umm el-‘Umdan today.16

One final factor may identify the site as ancient Modi’in—its Arabic name Umm el-‘Umdan. Clermont-Ganneau understood the name to be literally a translation of the Arabic name, which means “Mother of the Columns.” We suggest another possible understanding of the name Umm el-‘Umdan: Note the similarity of the names ‘Umdan (

Admittedly, we have not found an inscrןiption at the site with its ancient identification. But we present our evidence here demonstrating that Umm el-‘Umdan is the likely home of the Maccabees—Modi’in.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Andrea Berlin and Geoffrey B. Waywell, “Monumental Tombs from Maussollos to the Maccabees,” BAR 33:03.

Endnotes

Josephus, Antiquities XIII.210–211, Ralph Marcus, ed. and trans., Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1976). Josephus probably copied from 1 Maccabees 13:25–30.

Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873–1874, vol. II (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1896), pp. 82–83.

Claude R. Conder and Horatio H. Kitchener, Survey of Western Palestine, vol. III, Judaea (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1883), p. 127, sheet XVII.

The wall paintings were examined and identified by Dr. Sylvia Rozenberg of the Israel Museum. They were dated to the Hasmonean-Herodian period in the first century B.C.E., prior to the year 15 B.C.E., based on their style. Similar paintings were exposed in Jericho, Jerusalem and elsewhere. See Sylvia Rozenberg, Enchanted Landscapes: Wall Paintings from the Roman Era (Ramat Gan: R. Sirkis, 1993), pp. 147–152.

A similar assemblage of pottery vessels was discovered at Herodion; see Rachel Bar-Nathan, “Pottery and Stone Vessels of the Herodian Period,” in Ehud Netzer, ed., Greater Herodium (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, 1981), pp. 54–70.

The pottery vessel assemblage found at Jericho was of local production. The absence of imported vessels is explained by a ban imposed by Jewish Law; see Rachel Bar-Nathan, “Summary and Conclusions,” in Ehud Netzer, ed., Hasmonean and Herodian Palaces at Jericho, Vol. III: The Pottery (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2002), pp. 196–199.

Regarding this ban, see Amos Kloner, The Necropolis of Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period, Ph.D. dissertation (Jerusalem: The Hebrew Univ. of Jerusalem, 1980), p. 150 [Hebrew].

Josephus, Antiquities XII.265–266, XII.268; Eusebius, “Modiin,” in Erich Klostermann, ed., Das Onomastikon der Biblischen Ortsnamen, GCS11 (Hildsheim, G. Olms, 1966), p. 132, 1.16; Yoram Tsafrir, Leah Di Segni and Judith Green, “Modiin,” Tabula Imperii Romanii: Iudaea, Palaestina (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), p. 188.

Michael Avi-Yonah, Madaba Map—Translation and Interpretation (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1953), p. 135 [Hebrew].

William of Tyre mentioned it was located next to Emmaus; see William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea I, VIII, c1, Emily A. Babcock and A.C. Krey, eds. and trans. (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1943), p. 339. Theoderich identified it in Bel-Mont, which is Zuba; see Theoderich’s Description of the Holy Places: Circa 1172 A.D., Aubrey Stewart, ed. (London: Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1897), p. 57. Fetellus noted that “Mount Modiin from where Mattathias, father of the Maccabees came, is located nine miles from Jerusalem, on the road that leads past Rimta, where one can see the two seas: the Mediterranean Sea and the Dead Sea,” and that “one can still see the gravestones of Mattathias, his four sons and two grandsons”; see: Melchior de Vogüé, Les églisesde la Terre Sainte (Paris: V. Didron, 1860), p. 429, and Description of Jerusalem and the Holy Land by Fetellus, James R. Macpherson, ed. (London: Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1897), p. 44.

In the Onomasticon of Eusebius it is mentioned that “Modiin is a village of Lod”; Eusebius, Das Onomastikon, p. 132.

Modi’in appears on the Madaba Map close to the border between the mountainous region depicted on a dark background and the area of the foothills, which is portrayed on a light-colored background.

For the imperial roads that connected Jerusalem to Jaffa, see: “Modiin,” in Mosche Fischer, Benjamin Isaac and Israel Roll, eds., Roman Roads in Judea, II: The Jaffa-Jerusalem Roads (Oxford: BAR International Series, 1996), pp. 67–85; and also Israel Roll, ‘The Roman Road Network in Eretz Israel,” Qadmoniot IX, vol. 34–35 (Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum, 1976), pp. 43, 46–47 [Hebrew]; Israel Roll, “Transportation Routes from Jaffa to Jerusalem in the Roman and Byzantine Periods,” in Ely Schiller, ed., Zev Vilnay’s Jubilee Volume, II (Jerusalem: Ariel Publishing House, 1987), pp. 120–128 [Hebrew]. Regarding the imperial road from Emmaus-Bet Horon, see Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judea, pp. 85–87; Israel Roll and Etan Ayalon, “Judea and Samaria: Roman Roads and Milestones,” in Ayala Sussmann and Inna Pommerantz, eds., Excavations and Surveys in Israel, 3, no. 7 (Jerusalem: Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, 1984), p. 61 [Hebrew]; and Hananya Hizmi, “A Milestone on the Emmaus—Bet Horon Road,” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 95 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1990), p. 76 [Hebrew].

This road was part of the internal road network, not marked by milestones, which was paved between the imperial roads. The road appears on the British survey map from the 19th century; see Conder and Kitchener, Survey of Western Palestine, vol. III, p. 73. The eastern mountainous part was identified in the British survey map as a “Roman road” and was referred to as “Ma’aleh Bet Likia” in A. Milstein and A. Tepper-Amit, “Ma’alot Benyamin to Jerusalem—a Military and Topographic Analysis,” in Ze’ev H. Erlich and Ya’acov Eshel, eds., Judea and Samaria Research Studies, vol. 2, no. 4 (Kedumim-Ariel: Research Institute, The College of Judea and Samaria, 1993), pp. 82–83 [Hebrew]. The western part of the road was identified on the British survey map as an “ancient road” and was dated to the Roman period based on its characteristics, manner of pavement and the sites located alongside it; see Conder and Kitchener, Survey of Western Palestine, vol. III, sheet XVII, and Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judea, p. 99. The scholars assumed that the entire length of this route was used during the Roman period and constituted an alternative to the two main imperial roads that passed north and south of Umm el-‘Umdan. This route served as a main artery between Jerusalem and the coastal plain in the Crusader period in the 12th and 13th centuries C.E. In the Ottoman period the route was renovated and was in use until it was replaced in the 19th century by the Ramla-Latrun road; see Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judea, pp. 85–87, 98–99.

‘Aditayim, which is now Hadita’, identified with Tel Hadid; Kfar Ruta, identified with Horbat Kfar Ruth; Bet Horon, which is Ma’aleh Bet Horon; and ‘Anab which is now ‘Anaba, identified with Anaba.

Some examples include: Khirbet a-Latatin, identified with To Anaton, which appears on the Madaba Map (at the ninth [mile from Jerusalem]). The sound of the ruin’s name preserves the ancient name, though the meaning of the Arabic name, Latatin, is “limekiln,” and these were indeed discovered at the site Diyukh. The sound of the latter ruin’s name preserves the ancient name Doq, but the meaning of the Arabic name is “roosters”; see Yoel Elitzur, Ancient Toponyms in the Land of Israel: Preservation and History (Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi Press, 2012), p. 435 [Hebrew].