On Tuesday morning, June 7, 1099, the knights of the First Crusade caught their first glimpse of Jerusalem—from a height near the campsite where they had spent the night. The Crusaders called the hill Mons Gaudii—Mount Joy, or Montjoie in Norman French. The Holy City had finally come into view only after a long, grueling and bloody three-year military campaign.

It was from here that pilgrims for centuries thereafter would dismount, display their crosses and walk to Jerusalem.

A 12th-century pilgrim named Theodoric describes the scene at Nebi Samwil, just a few miles from the Holy City:

[There] stands a small church where the pilgrims have their first view of this city and, moved with great joy, display their crosses. They take off their shoes, humbly trying to seek the person who for them was pleased to come to this place as a poor and humble man.1

Another pilgrim, the Russian abbot Daniel, describes the emotion:

All dismount from their horses and place little crosses there and bow to the [Church of the] Resurrection on the road to town. And no one can hold back tears at the sight of that desired and the holy places where Christ our God suffered his passion for the sake of us sinners. And all go on foot in great joy towards the city of Jerusalem.2

Today the site is called Nebi Samwil (the “Prophet Samuel” in Arabic). The identification of the site in Biblical times has been the subject of scholarly debate for some time.3

As early as 1835, the great American explorer Edward Robinson, who successfully located so many Biblical sites, identified Nebi Samwil as Biblical Mizpah. In the early 1930s, the prominent American archaeologist William Foxwell Albright also identified Nebi Samwil with Biblical Mizpah, where, according to the Bible, Samuel presented Saul to the people as the first king of Israel (1 Samuel 10:17–24).4

This was called into question, however, when Tell en-Nasbeh, a mound about 8 miles northwest of Jerusalem, was excavated in the 1920s and 1930s and the excavation hit remains from the Biblical period. This, plus the similarity in the modern and ancient name (Mizpah/Nasbeh) seemed to make the case for Tell en-Nasbeh as Mizpah. Indeed, the excavators pronounced it to be Biblical Mizpah and almost everyone accepted this identification.

Albright did not change his view, however, even after the excavations at Tell en-Nasbeh.5 He continued to maintain that Nebi Samwil was Biblical Mizpah. Following our renewed excavations conducted at the Nebi Samwil site, we, too, faced the question: Was Nebi Samwil or Tell en-Nasbeh the site of Biblical Mizpah?

In fact, not a single bit of evidence unequivocally proves Tell en-Nasbeh’s identification as Mizpah. The archaeological finds from Tell en-Nasbeh could suit the identification of any other Iron Age site; and the seeming phonetic similarity between Mizpah and Tell en-Nasbeh is linguistically baseless. The case for Tell en-Nasbeh as Mizpah is founded on a subjective interpretation of the Biblical sources and their adaptation to the archaeological finds, not on any certain identification.

I believe Albright was right: Nebi Samwil is Mizpah.

Mizpah is one of the Benjaminite cities listed in Joshua 18:25–26: Gibeon, Ramah, Beeroth, Mizpah, Chepirah and Mozah. If there is any geographic order in this list, Mizpah cannot be at the northern end of Benjamin, where Tell en-Nasbeh is situated, but in the middle of Benjamin. The Biblical description of Benjamin’s northern border does not mention Mizpah (Joshua 18:12–13).

In the Bible, Mizpah was an important religious site in the period before Israelite religious observance was centralized at the Temple in Jerusalem. There was an altar at Mizpah, and the tribes came there to take an oath (Judges 21:1–7).

Mizpah also figures prominently in the conflict between the Israelites and the Philistines. In the days before there was a king in Israel, Samuel assembled “all Israel” at Mizpah. There they fasted and confessed their sins. Samuel sacrificed a suckling lamb as a burnt offering, confirming the existence of an altar at the site and the important religious character of the place. The people also engaged in some kind of water-lustration ceremony. And “Samuel cried out to the Lord on behalf of Israel.” And “the Lord thundered mightily against the Philistines that day” (1 Samuel 7:5–11).

When Samuel rode circuit as a judge, one of the places he stopped was Mizpah (1 Samuel 7:16). Thus, from its earliest history, Mizpah was associated with Samuel.

In the internecine war between Judah and Israel after the breakup of the United Kingdom, King Asa of Judah fortified several sites, including Mizpah (1Kings 1Ki; 2 Chronicles 16:6).6

When, hundreds of years later, the Judean exiles returned from Babylon, Mizpah continued to be inhabited. People from Mizpah helped rebuild the wall of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 3:7). Mizpah even had a mayor or governor, who participated in the rebuilding work (Nehemiah 3:19).

Jeffrey R. Zorn, in his BAR article on Tell en-Nasbeh, opts for that site as Mizpah, but he recognizes that Nebi Samwil was once a contender for Mizpah.a He quickly eliminates it, however: “If a site is to be identified as Mizpah, it must have remains from Iron Age I [the period of the Judges, 1200–1000 B.C.E.]. By this test, Nebi Samwil, the only alternative to Tell en-Nasbeh, fails.”

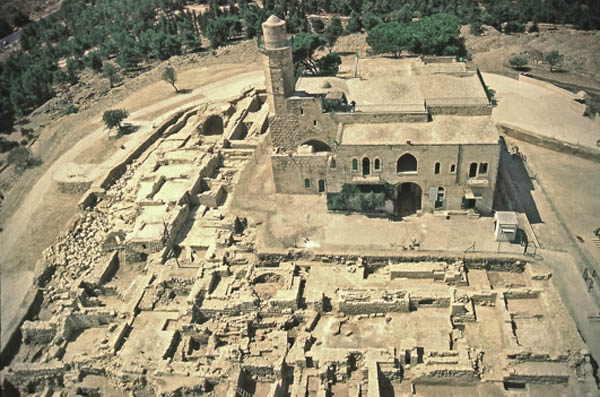

Zorn based his conclusion regarding the occupation of Nebi Samwil on a survey of the site, although noting that a recent excavation had not yet been published. I directed that excavation of Nebi Samwil from 1992 until 2003.7 I am happy to report the results to BAR readers.

It’s always dangerous to draw a conclusion on the basis of what was not found, especially if it was not found in a survey of a site. But that’s what Zorn did in BAR. There is still a lot that we have not found, but there is a lot that we have found.

In our excavations, we did not find any remains from the time of the Judges, the period archaeologists call Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), but this should not be surprising: Nothing from this period has been found at most sites with a Biblical identification in the Land of Benjamin. We did, however, uncover numerous finds from the First Temple period (1000–586 B.C.E.). Interestingly enough, we found not a single structure or even a standing wall from this period. On this basis, it might be tempting to conclude that the site was unoccupied at this time. But in the fill inside dwellings of the Hellenistic residential quarter, we found pottery easily identifiable as coming from the First Temple period, including the well-known l’melech (“belonging to the king”) seal impressions on jar handles from the late eighth century B.C.E. In addition, some of the foundations of walls from the Hellenistic residences may go back to the First Temple period. All this suggests caution in concluding that the site was not occupied until later.

Nebi Samwil sits on a high hill 3,000 feet above sea level. This, too, favors the identification of Nebi Samwil as Mizpah. Two perennial springs flow on the north and east—the Spring of Samuel and the Spring of Hannah (Samuel’s mother). Winding around the hill are terraces on which verdant fruit trees, vineyards and olive trees flourish. Even more important, the hilltop has a commanding view over key ancient highways (the main road from the coastal plain to Jerusalem and the north-south road from western Samaria to Jerusalem). In addition, it provides a unique observation point in all four directions. This may well have had something to do with its ancient name—Mizpah means “lookout.”

Other geographical considerations suggest that Nebi Samwil is to be identified with Mizpah. Mizpah and Gibeon are frequently mentioned together in the Bible, a fact that alludes to their geographical proximity. For example, the people of Gibeon and Mizpah aided in the rebuilding of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 3:7). Nebi Samwil and Gibeon (modern el-Jib) are only about a mile apart. It is nearly 3 miles, however, from Tell en-Nasbeh to Gibeon.

In the second century B.C.E. at the beginning of the Jewish revolt against the Assyrian (Seleucid) overlord Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Jewish leader Judah Maccabeus renewed the ancient ceremony of assembling the people at Mizpah that began with Samuel: “They gathered together and went to Mizpah, opposite Jerusalem, because Israel formerly had a place of prayer in Mizpah” (1 Maccabees 3:46–47). In no way can Tell en-Nasbeh be said to be opposite Jerusalem. Nebi Samwil is less than 5 miles northwest of Jerusalem and offers a breathtaking view of the Holy City. By contrast, Tell en-Nasbeh is more than 8 miles north of Jerusalem, and there is no line of sight between the tell and Jerusalem.

When Judah Maccabeus rallied his troops at Mizpah, he was acting out of religious tradition and for reasons of military strategy. Antiochus’s troops were at Emmaus on their way to Jerusalem. Nebi Samwil is on the main road between Jerusalem and Emmaus (Nikopolis). Tell en-Nasbeh, on the other hand, would be of no military value in the defense of Jerusalem. There is no logic to rallying the Jewish troops at Tell en-Nasbeh, neither to attack Emmaus nor to defend the road to Jerusalem.

I have referred to the few finds we uncovered at Nebi Samwil from the First Temple period. The next archaeological time slot is known as the Persian period because the Persians, who succeeded the Babylonians as the world’s superpower in the sixth century B.C.E., allowed the Jews to return from exile to the Promised Land. Judah, now known as Yehud, became a Persian province. From the Persian period we found some jar handles stamped “Yehud” and a few silver coins.

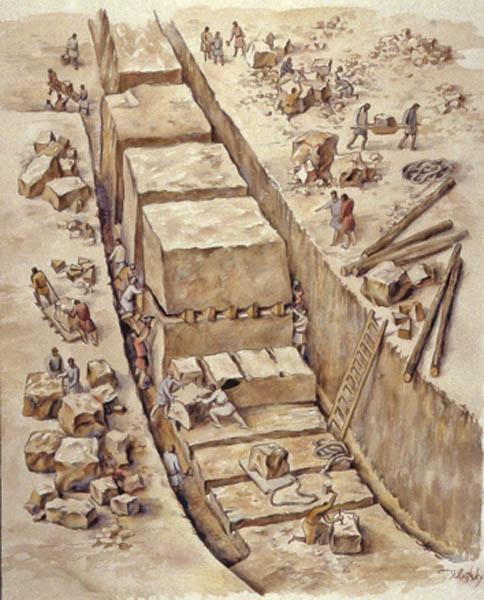

Why was so little found from these early periods? The site was subsequently used as a stone quarry for later construction atop the hill (much like Jerusalem). The Crusaders used these quarried blocks to build monumental structures on the site. As a result, even relatively late Hellenistic remains were almost totally destroyed. Indeed, the only remains of the Hellenistic period that we found—a residential quarter—were located on the fringe of the excavation area where the Crusader construction had not extended. The Hellenistic settlement must have been quite large, however. Based on the size of the building blocks, doorposts and lintels of the bottom story, the Hellenistic buildings clearly had at least a second story, if not more. One of the houses that survived in better shape than most had rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The walls were coated with high-quality plaster. We also uncovered nearly 200 feet of a Hellenistic street with a tiled drain underneath. Almost nothing, however, was discovered in the area of the Crusader construction.

The site was abandoned toward the end of the second century B.C.E. We aren’t sure why, but the political situation gives us a good idea. The Hellenistic city was constructed when the Seleucids ruled the country from their capital in Syria. I have already referred to the Maccabean revolt, which was ultimately successful (hence, the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah) and ended with the establishment of an independent Jewish state. The Maccabean sons who led the revolt were replaced in the mid-second century B.C.E. by the Hasmonean dynasty, which combined both the kingship and the high priesthood. Successive Hasmonean leaders expanded the borders of Judea through military conquests. With the expanded borders of the Hasmonean kingdom, the site of Nebi Samwil was no longer needed as a military fort to protect the Jerusalem approach, so the site was abandoned.

A religious reason also accounts for the abandonment of the site at this point. If, as I believe, the site was ancient Mizpah, it was not only a fort to protect Jerusalem but also an important ancient religious site. At this point, however, the Hasmonean leaders had centralized religious observance in the Temple at Jerusalem. Indeed, that was the exclusive place where the Israelite God was to be addressed. The Hasmoneans destroyed all other sanctuaries, whether dedicated to the God of Israel or to pagan gods. Hasmonean rulers committed to Jerusalem would not want to take the chance that the ancient religious center at Mizpah would be revitalized and revived as a religious center. What better solution than to abandon the site, especially since, in an expanded kingdom, it was no longer needed for the defense of Jerusalem.

In the Byzantine period (fourth–seventh centuries C.E.), a Christian monastery was built on the site. In my view, the builders did not believe they were building their monastery over the tomb of Samuel. That tradition developed later. I believe the Byzantine monastery at Nebi Samwil was intended not as a memorial to the prophet’s tomb, but simply to honor him and his association with the site of Mizpah, of which there must have been some memory or tradition.

The reason I believe the builders of the monastery did not believe the cave below the monastery church was Samuel’s tomb is that Christian tradition had already identified his tomb as being located elsewhere. In the fourth century, the church father Eusebius had identified Samuel’s birthplace and the site of his tomb as Arimathea-Rantis (Biblical Ramah), near Lydda. In the early fifth century, Jerome reports that the Byzantine emperor Arcadius transferred Samuel’s bones to Chalcedon in Thrace.8 The monastery at Nebi Samwil was not built until after this—in the sixth century.

The Byzantines were undoubtedly familiar with these Christian writings and knew of the tradition concerning the transferal of Samuel’s bones to Thrace. They also were versed in the writings of Eusebius and knew that Nebi Samwil could not be identified as Ramah, Samuel’s birthplace and the site of his burial, according to the Bible. On1y the identification of Nebi Samwil with Mizpah and its tradition of sanctity connected with Samuel can account for the establishment of the monastery named after him.

The monastery continued to function even after the Arab conquest in the seventh century. In pottery kilns from the Umayyad period (seventh–eighth centuries C.E.), we recovered dozens of vessels stamped in Arabic Deir Samwil (“the Monastery of Samuel”). The Muslim geographer al-Muqaddasi (c. 985) mentions the monastery of St. Samue1.9 Interestingly, he uses the Hebrew version of the name, Shmu’el, and not the Greek form, Samwil. In the 13th century, Ya¯qu¯t also mentions Ma¯r S.amwi¯l (ma¯r in Syriac means “saint”).10 None of these references connect Nebi Samwil with the burial site of Samuel, but rather only to the monastery of Samuel.

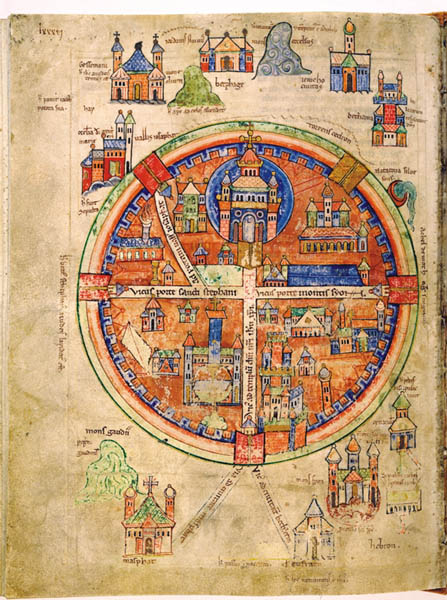

In a colorful 12th-century map of Jerusalem, several outlying sites are pictured and referred to, including Nebi Samwil. Denominated on the map as Mons Gaudii (Latin for “Mount of Joy” and Norman French “Montjoie”), it is portrayed simply as a mountain. Adjacent to it, its church is depicted and labeled “Masphat.” The road from there to Jerusalem is labeled Via ad civitatem Masphat, “the Way to the city of Masphat.” In short, Montjoie/Nebi Samwil and Masphat are one and the same. And Masphat is the Latin for Mizpah!11 This mapmaker surely thought Nebi Samwil was Mizpah. It is likely that in the 13th century, the site was also known as Masphat, that is, Mizpah.

It is only in the 15th century, in a work by the medieval Arab historian Mujar ed-Din, that we find the first mention of Nebi Samwil as the site of Samuel’s tomb.

The Crusaders almost completely destroyed the Byzantine monastery on the summit of the hill. Under Crusader walls, we found some white mosaic tesserae from the monastery building. In a well-preserved monastery pottery kiln from the Umayyad period, we discovered numerous handles from large jars with seal impressions stamped in Arabic, one reading Deir Samwil. Nearby was an elaborate winepress from the monastery with a mosaic treading floor connected to a hewn and plastered collecting vat.

In addition to pottery from the monastery, we also recovered an unusually large number of coins. The sequence begins in the early fourth century and continues uninterrupted down to the tenth century. A particularly large number of coins (more than 125) date to the fifth and sixth centuries. The sequence continues into the Umayyad period (seventh–eighth centuries) and the Abassid period (eighth–tenth centuries). The monastery was probably a major pilgrimage site in the Byzantine and Muslim periods. Among the coins were some from the kingdom of Axum in east Africa (modern Ethiopia), which gives an idea of the geographical range of the pilgrims. The large number of coins also suggests commercial activity at the monastery. Large cisterns, the wine-press and pottery kilns tend to support this suggestion.

Finally, at the onset of the Fatimid period in the tenth century C.E., the monastery was abandoned—at least so we presume based on the archaeological evidence.

The Crusaders then built a fortress here. Even when the Crusaders were militarily successful against the Muslim forces, they were limited by the fact that the Christians were few in number and were trying to rule over a vastly larger Muslim population. This great disparity in numbers forced the Crusaders to build an array of fortresses across the Holy Land from which they could impose their own feudal-style rule.

The strategic importance of Nebi Samwil was quickly recognized by the Crusader forces. As noted earlier, it was from here that they first caught site of Jerusalem. From here, signals could be sent to

Jerusalem, and posted guards could survey the roads that led west to the low hill country of the Shephelah and east to the Samaria hills.

The initial settlement of Nebi Samwil in the Crusader period was based purely upon strategic considerations. The Crusaders quickly built a mighty fortress here with a number of towers. A Crusader military order named Mons Gaudii (Mount of Joy) was established at Nebi Samwil.

The Crusader complex also included a large church (about 100 by 125 ft) with associated monastery. In 1157, the Mons Gaudii church is mentioned for the first time—in documents of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In another source, it is called the Church of St. Samuel.12

Outside the fortress, the Crusader complex included encampment areas, an inn for pilgrims, two stables and two extremely deep cisterns.

The fortress’s walls were unfortunately found in ruins, most likely destroyed by Salah ed-Din on his way to conquering Jerusalem.

Both the Crusader fortress and its church were built of the soft, yellowish limestone quarried on the hill, thus avoiding the need to transport stones over great distances.

In 1187, a short time before Salah ed-Din’s conquest of Jerusalem, the monastery of St. Samuel was pillaged by the Muslims. Its monks found refuge in the monastery of St. John in Acre.13 Nebi Samwil was then used as a rear base by the Muslim forces and later purposely destroyed, as were other Christian cities. The Muslims wanted to insure that if the Crusaders reconquered these sites, they would not be able to entrench themselves in existing buildings.

In the 12th century, a mosque was built on Nebi Samwil, integrating architectural elements of the Crusader church. The mosque, much smaller than the Crusader church, was built within the nave of the church.

In the basement of the mosque is the cave that is supposed to be the burial place of the prophet Samuel. As noted earlier, it is a late, unhistorical tradition. The cave lies about 10 feet below the pavement of the mosque’s upper hall. A wooden column in the center of the mosque marks the location of the supposed tombstone of the prophet beneath.

The cave itself measures about 36 by 15 feet. It includes a central vaulted hall and two additional small rooms. At the western end of the cave is a large cenotaph that traditionally denotes the tomb.

Originally two entrances via staircases led from ground level down to the cave. One was blocked for many years and only recently reopened. At that time, we were able to confirm that the cave was initially built in the Crusader period and was an integral part of the Crusader church. There is no hint of a structure here prior to the Crusader period. The cave must be the crypt of the Crusader church, originally intended for the burial of church dignitaries. As is usually the case, it was constructed underneath the church’s nave. With time, the tradition developed connecting it to Samuel’s tomb.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Endnotes

Libellus de Locis Sanctis, 44/41; J. Wilkinson, J. Hill and W.F. Ryan, trans., Jerusalem Pilgrimage 1099–1185 (London, 1988), p. 310.

Daniel the Abbot, Ch. VIII-IX; J. Wilkinson, et al., Jerusalem Pilgrimage 1099–1185, pp. 126–127.

Late Jewish sources identified the site with Ramah, Samuel’s home and burial place: “Samuel died, and all Israel gathered and made lament for him, and they buried him in Ramah, his home” (1 Samuel 25:1; 28:3). Samuel’s parents, Elkanah and Hannah, came from Ramathaim-zophim, in the Ephraim hill country (1 Samuel 1:1), but at some point Samuel went from his parent’s house to dwell in Ramah in Benjamin.

Some scholars have also identified Nebi Samwil with Beeroth, one of the Gibeonite cities (Joshua 9:17) and even with Gibeon, where Solomon offered sacrifices (1 Kings 3:4).

W.F. Albright, “The Site of Mizpah in Benjamin,” Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 3 (1923), pp. 110–121.

In my opinion, the narrative of this war indicates that Mizpah is to be identified with Nebi Samwil and not with Tell en-Nasbeh. King Baasha of Israel advanced against Judah and fortified Ramah (identified with er-Ram) to block the road to Jerusalem for anyone supporting Asa. Asa sent emissaries to Damascus to bribe King Ben-hadad of Aram and request that he break his alliance with Baasha. Ben-hadad agreed to this proposal and attacked Israel’s northern cities. Baasha lifted the siege and the fortification of Ramah in order to protect his northern cities. Asa then took the stones and timber of Ramah, and built two fortresses to defend the roads to Jerusalem—Geba of Benjamin, and Mizpah (1Kings 15:17–22; 2 Chronicles 16:1–6).

Geba of Benjamin is Gibeah of Saul, and is identified with Tell el-Ful. Tell en-Nasbeh is some 4 miles away from Tell el-Ful; there would be no military logic in the fortification of two cities on the same longitudinal road that were distant from one another, and that could be bypassed by the northern army. After the siege imposed by Baasha, Asa should have engaged in defensive measures and not in expanding his territory to Tell en-Nasbeh; defensive steps imply retrenchment, not expansion. This was especially so since the Israelite army could have outflanked the northern road and taken the western route to Jerusalem via Nebi Samwil. For military reasons, therefore, Asa preferred to fortify Mizpah (that is Nebi Samwil), which is a central, lofty site that controls the northwest road to Jerusalem. Nebi Samwil is very close to Tell el-Ful/Geba of Benjamin and is in line of sight with it; it is situated on the major road that leads from northwestern Samaria and the coastal plain, which is no less important for the defense of Jerusalem. Accordingly, Asa’s activity clearly indicates the superiority of the identification of Mizpah with Nebi Samwil, and not with Tell en-Nasbeh.

On behalf of the Staff Officer in the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria. During the first seasons, the dig was supervised by Michael Dadon and in more recent seasons by Benjamin Har-Even.

Against Vigilantius 5.343; trans. W. Fremantle, The Principal Works of St. Jerome (A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene fathers of the Christian Church 6, [Michigan, 1983]), p. 419.

Al Muqaddasi, 188. Translation of this passage can be found in Guy Le Strange, Description of Syria including Palestine by Mukaddasi (London: Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society Library 3, 1896), p. 89.

Ya¯qu¯t, IV.391. Translation of this passage can be found in Guy Le Strange, Palestine under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from 650 to 1500 A.D. (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1890), p. 433.

Y. Tsafrir, L. Di Segni and J. Green, Tabula Imperii Romani Judea/Palestina (Jerusalem, 1994), pp. 180–181.