One of the pivotal figures in the death of Jesus is the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate.1 He alone wielded the authority to execute by crucifixion. Yet Christian memories of Pilate are remarkably varied. The most striking example is the tradition of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church that considers Pilate a saint.

How can it be that the man who murdered Jesus came to be considered a saint by some of his followers?

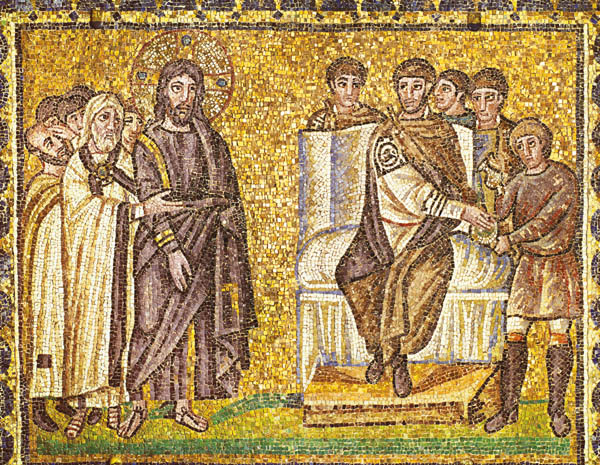

In the canonical Gospels, Pilate attempts to release Jesus but, ultimately, succumbs to pressure from Jesus’ accusers to execute him instead. Many scholars consider this depiction of Pilate’s hesitation a Christian invention to mitigate Pilate’s complicity in Jesus’ death because of the unseemly image of a Roman official executing the founder of the Christian faith.

Matthew alone presents the iconic depiction of Pilate washing his hands of the affair—a detail that is not repeated in any other gospel. The episode belongs to Matthew’s tendency to recolor his sources in an anti-Jewish montage. Can it be a coincidence that in the same scene we hear the malediction by the Jewish leaders—“His [Jesus’] blood be on us and on our children!” (Matthew 27:25)? According to Matthew, after Pilate washes his hands of responsibility, he instructs Jesus’ accusers, saying, “See to it yourselves” (Matthew 27:24). It is at this point that Matthew’s additional material ends, and he rejoins Mark’s description of Jesus being led away to be executed—not by his Jewish accusers, but by Pilate’s own soldiers (Matthew 27:27–31; Mark 15:16–20), while Luke specifies the Roman military culpability when presenting the crucifixion itself (Luke 23:36, Luke 23:47).

While Matthew may have exploited Pilate’s hesitation for his own purposes, it is less certain whether Pilate’s character on display is entirely a Christian creation. We face similar challenges in identifying the historical Pilate in the reports of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus and the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria. How do we sort through these conflicting presentations of a figure who played such an important role in both Jewish and Christian history?

Archaeology can help. Discoveries made in Israel during the past 60 years contribute material evidence to the episodes involving Pilate presented by Josephus, Philo and the New Testament. Although this new evidence does not answer all our questions, it provides important information that can measure the individual author’s use of historical sources.

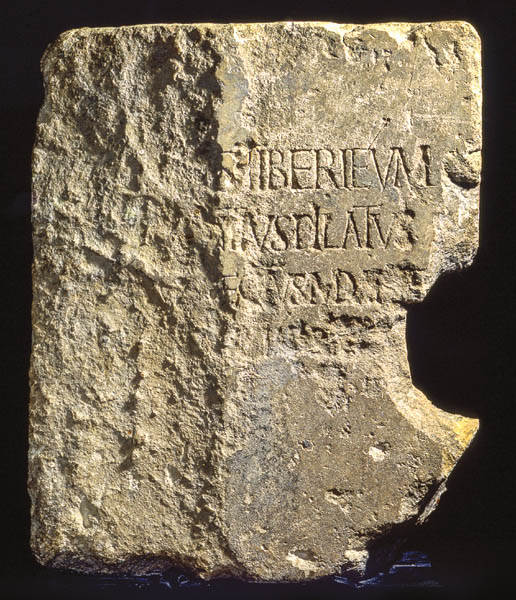

The most frequently cited historical contribution by archaeology concerns Pilate’s title and responsibilities in the Roman province of Judea. A Latin inscription found at Caesarea Maritima that mentions Pilate’s name provides physical evidence of his presence in Judea during the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius. In Latin, the damaged inscription reads (restored parts in brackets):2

[Dis Augusti]s Tiberiéum

[—Po]ntius Pilatus

[ praef]ectus Iuda[ea]e

[fecit, d]é[dicavit]

This roughly translates as “[Po]ntius Pilate, [pref]ect of Jud[e]a, [made and d]e[dicated] Tiberieum to the [divine August]us.” When archaeologists found this inscription, which was carved into a limestone block, it had been reused as a step in the theater at Caesarea, but originally it would have served as a dedicatory plaque for another structure—the “Tiberieum” mentioned in the inscription. In all likelihood, Pilate was dedicating the Tiberieum to Emperor Tiberius.

This inscription clarifies the position Pilate held—correcting an error found in the writings of both Greek and Latin authors. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote at the beginning of the second century C.E., “Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilatus” (Annals 15:44). However, the Caesarea inscription indicates that Pilate was a Roman prefect, not a procurator. In the Roman Empire—at least initially—a prefect was an official with military responsibilities, whereas a procurator had primarily financial ones. This is a minor historical detail, but it demonstrates how archaeology helps us to present Pilate’s role correctly. Further, in Egypt and the Roman East, there were no procurators before Claudius’s reign (41–54 C.E.).

Until recently, Pilate’s coinage was generally understood to exemplify nothing but his callous disregard for those he ruled. Other governors in Roman Judea were careful not to incorporate decorations on their coins that would offend the local Jewish population.3 They adopted images that were current also in Jewish decorations. Not so with Pilate. His coins have the distinction of being the only ones minted by a Roman governor in Judea with images that borrowed recognizable instruments from the imperial cult, such as the lituus (curved wand) or the simpulum (ladle).

Philo and Josephus report three accounts of conflict between Pilate and the Jewish population over religious matters: the episodes of (1) the military standards, (2) the shields and (3) the aqueduct. Scholars are divided as to whether Pilate’s missteps were born out of ignorance or malice toward the Jews or devotion to the imperial cult and intent to assimilate Judea into the Roman Empire.

The episode of the standards is presented in both Josephus’s Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews, and they do not differ markedly in detail:

Now Pilate, the procurator of Judea, when he brought his army from Caesarea and removed it to the winter quarters4 in Jerusalem, took a bold step in subversion of the Jewish practices, by introducing into the city the busts of the emperor that were attached to the military standards, for our law forbids the making of images. It is for this reason that the previous procurators, when they entered the city, used standards that had no such ornaments. Pilate was the first to bring the images into Jerusalem and set them up, doing it without the knowledge of the people, for he entered at night. But when the people discovered it, they went in a throng to Caesarea and for many days entreated him to take away the images. He refused to yield, since to do so would be an outrage to the emperor; however, since they did not cease entreating him, on the sixth day he secretly armed and placed his troops in position while he himself came to the speaker’s stand. This had been constructed in the stadium, which provided concealment for the army that lay in wait. When the Jews again engaged in supplication, at a pre-arranged signal he surrounded them with his soldiers and threatened to punish them at once with death, if they did not put an end to their tumult and return to their own places. But they, casting themselves prostrate and baring their throats, declared that they had gladly welcomed death rather than make bold to transgress the wise provisions of the laws. Pilate, astonished at the strength of their devotion to the laws, straightway removed the images from Jerusalem and brought them back to Caesarea.

(Antiquities 18.55–59; cf. Jewish War 2.169–174)

Archaeology has yet to shed light on the setting of this protest. Previous excavations in Caesarea revealed the Herodian circus for chariot races and the Herodian theater, as well as the much larger and later circus built probably under Hadrian.a However, none of these structures can confidently be identified with the (Herodian) stadium for athletic contests, which might be the site referred to by Josephus in his above description of the violent protests that took place in Caesarea in response to the introduction into Jerusalem of Roman military standards with the image of the emperor.

According to Josephus, this event occurred at the beginning of Pilate’s governorship. Pilate was the fifth Roman prefect appointed in Judea, following Coponius (6–9 C.E.), Marcus Ambivulus (or Ambivius; 9–12), Annius Rufus (12–15) and Valerius Gratus. There is some question about the length of Gratus’s term. Josephus reports, “Gratus retired to Rome having stayed 11 years in Judea” (Antiquities 18.35). This is why most histories date the beginning of Pilate’s administration to 26. Recently, however, Josephus’s chronology has been questioned, and it has been suggested that Gratus, like his predecessors, served only three years and that Pilate followed him in 18/19.5

This revised timetable is buttressed by an observation regarding the role of the Jewish high priest. Josephus records four high priests deposed by Gratus in quick succession—within three years (Antiquities 18.34–35). If Pilate had been appointed soon thereafter, this might explain the apparent change in policy toward the length of term for high priests. The four priests Gratus removed were followed by Joseph Caiaphas, who served as high priest almost 20 years, ending his service in the same year that Pilate was deposed, in 36/37 (Antiquities 18.85—89). Both the length of Caiaphas’s tenure and his removal at the time of Pilate’s deposition suggests that their service may have been more closely aligned than is often recognized.

If Pilate’s tenure was longer (18–36), it might also explain the greater reporting Josephus gives to Pilate as compared to the other Roman governors. Further, it would be consistent with Emperor Tiberius’s preference to leave governors in place if possible (Antiquities 18.170; Tacitus, Annals 1.80; Suetonius, Tiberius 41).

Recent scholarship suggests that the second conflict story between Pilate and the Jewish population of Judea—Philo’s account of the gilded shields (On the Embassy to Gaius 299—305)—is likely a refashioned version of the episode of the military standards recorded by Josephus.6 The accounts do bear striking similarities, and the three points of substantive difference between the accounts of the standards and the shields are precisely at those points that serve Philo’s argument to dissuade Gaius Caligula from installing a golden statue of himself on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.7

The third conflict story concerned the prefect’s efforts to improve the aqueduct to Jerusalem. Josephus recounts:

On a later occasion he [Pilate] provoked a fresh uproar by expending upon the construction of an aqueduct the sacred treasure known as Corbanas; the water was brought from a distance of 400 furlongs. Indignant at this proceeding, the populace formed a ring round the tribunal of Pilate, then on a visit to Jerusalem, and besieged him with angry clamor. He, foreseeing the tumult, had interspersed among the crowd a troop of his soldiers, armed but disguised in civilian dress, with orders not to use their swords, but to beat any rioters with cudgels. He now from his tribunal gave the agreed signal. Large numbers of the Jews perished, some from the blows which they received, others trodden to death by their companions in the ensuing flight. Cowed by the fate of the victims, the multitude was reduced to silence.

(Jewish War 2.175–177; cf. Antiquities 18.60–62)

Once again archaeology has unearthed valuable information that provides added testimony to Josephus’s historical account. Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem identified the aqueduct in question with a branch of the Jerusalem aqueduct system that originated south of Bethlehem from the higher elevations of the ‘Arrub spring and fed into the so-called Solomon’s Pools, from where water flowed through Bethlehem to Jerusalem.8

An archaeological survey indicates that the ‘Arrub aqueduct dates from the Hellenistic period and continued in use during the time of the Hasmoneans, Herod the Great, Pontius Pilate and others. Pilate’s efforts focused on the beginning stages of the water system in an attempt to increase the water supply with an extension from ’Ein Keweiziba to Solomon’s Pools.

Although the direct distance between its start at ’Ein Kuweiziba and its destination at Solomon’s Pools is only about 6 miles, the aqueduct is actually 24 miles long. The reason for its many meandersis inherent in the steep topography of the area and in the minimal use of tunnels, bridges and pipes to shorten its course.

Similar to the episode of the standards, Josephus places his report of the protest over Pilate’s seizure of funds from the Temple treasury at the beginning of Pilate’s governorship. If this is correct, then these two missteps may have resulted from a miscalculation by the new governor and may be aberrations in what was otherwise a peaceful period.

Pilate was caught by surprise by the Jewish resistance to his introduction of military standards into Jerusalem, but he was prepared for their demonstration against his use of funds from the Temple treasury. This time he met them with a calculated, violent response. Both Pilate’s misuse of funds and his murderous action fit his reputation recorded by Philo: “a man of an inflexible, stubborn and cruel disposition,” known for “his venality, his violence, his thievery, his assaults, his abusive behavior, his frequent executions of untried prisoners and his endless savage ferocity” (On the Embassy to Gaius 301; 302). Each of these characteristics is on full display in the reports of first-century eyewitnesses. While modern scholars may still have questions about particular historical details in the different accounts, and they may even have doubts about the accuracy of the reports, what is striking is the consistent portrait of the historical Pontius Pilate that is presented in different accounts by different authors from different perspectives.

It is worth noting that in Josephus’s report, we have no hint of protests by the Jewish high priest Caiaphas or the Temple leadership as to the misappropriation of Temple funds. Nor does Josephus give us an explanation for the source of the indignation by the Jerusalem crowds. The project was a public work that directly benefited the operation of the Temple. In similar instances, Roman governors were often expected to finance the endeavors. However, Temple funds were also allowed for such projects.

It is possible that the Temple funds seized by Pilate were specifically designated for sacrificial offerings.9 If so, the protest of the people was not simply about the use of funds from the Temple, but about the offerings that had been collected through the Temple tax and were set aside for the sacrifices in the Temple. It is well known that Caiaphas and the other Sadducean priests were not in favor of the custom of the half-shekel Temple tax.10 So their silence toward the misappropriation of these funds for purposes other than what they were designated comes as no surprise. In this account, we witness once again the convergence of the interests of Pilate and Caiaphas.

Pilate’s downfall came as a result of his violent reaction to a suspected insurrection by the Samaritans (descendants of Israelites who survived the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom and intermarried with the foreigners settled in that area by the Assyrians) at Mt. Gerizim. Josephus reports that Roman troops confronted the Samaritan crowd with force, and Pilate had the principal Samaritan leaders executed (Antiquities 18.85–89). The Samaritans complained to Vitellius, the Roman legate in Syria. He relieved Pilate of his position and sent a certain Marcellus to take charge of Judea. Pilate was ordered to return to Rome and face charges before Tiberius. In the end, however, fortune smiled on Pilate because Tiberius died while he was en route. Nothing again is heard about the disgraced prefect.

It seems more than a coincidence that when Vitellius visited Jerusalem, he found it necessary also to replace the high priest (Antiquities 18.95). Caiaphas had served for the entirety of Pilate’s tenure, and these two must have worked closely together. Pilate’s unpopularity with the local population—not just with the Samaritans but also with the Jews—may well have been similarly cast upon Caiaphas. Rabbinic accusations against the high priestly families in the first century C.E. come very close to the criticisms we hear about Pilate.11 Yet Vitellius’s actions in Jerusalem were only against Caiaphas and not the dynastic family of high priests that began with Caiaphas’s father-in-law, Annas. This is demonstrated by the fact that Vitellius replaced Caiaphas with his brother-in-law, Jonathan.

The removal of Caiaphas and Pilate in the same year suggests the two shared a very close association, not only in their arrival and departures from power, but also in their collaboration in governing Judea. Their close cooperation proved mutually beneficial with each holding the longest tenures for their respective offices in the first century.

As we have seen, archaeology increases our understanding of the complex figure of Pontius Pilate. Nothing in the physical settings of the historical accounts is inconsistent with the results of archaeological discoveries of the past 60 years—just the opposite.

We began with a question about the image of Pontius Pilate in the Gospels. While the New Testament sources should not be read as unvarnished history and are indeed in need of critical scrutiny, the historical Pilate that emerges from the pages of the extracanonical sources is not dissimilar to the person we meet in the Gospels. His weakness under public pressure and his penchant to overcompensate with a calculated and murderous reaction are eerily familiar. So, likewise, is the specter of his close collaboration with the Sadducean priests in Jerusalem—in particular the dynastic family that maintained control over the Temple longer than any other in the days of the Second Temple.

Josephus, Philo and the New Testament all portray a figure who felt no hesitation to do whatever was necessary to maintain Roman control in Judea. Yet the same calculated response witnessed in the tragic death of Jesus of Nazareth eventually proved to be Pilate’s undoing. Acting on false rumors, Pontius Pilate reacted violently against a gathering of Samaritans in the year 36, which resulted in his removal from office and his exodus from the pages of history.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Robert J. Bull, “Caesarea Maritima: The Search for Herod’s City,” BAR, 8:03; Barbara Burrell, Kathryn Gleason and Ehud Netzer, “Uncovering Herod’s Seaside Palace,” BAR, 19:03; Yosef Porath, “Vegas on the Med,” BAR, 30:05

Endnotes

Portions of this article will appear in a festschrift to honor James F. Strange. My purpose in both has been to demonstrate that historians need archaeologists and that archaeologists need historians.

See Shemuel Safrai and Menahem Stern, The Jewish People in the First Century, Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 1 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1974), p. 316. Other editions restore and interpret the inscription differently, but they all agree it reads “Pontius Pilate, prefect of Judea.”

Ya’akov Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins from the Persian Period to Bar-Kochba (Nyack, NY: Amphora Books, 2001), pp. 167—173.

This is likely the Antonia Fortress adjacent to the Temple precincts. See Ehud Netzer, The Palaces of the Hasmoneans and Herod the Great (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2001), pp. 123—125. Its close proximity to the sanctuary may have contributed to confusion in later periods in both Jewish and Christian memories. See Megillat Ta’anit 9: “On the third of Kislev the ensigns were removed from the [Temple] court.” Eusebius, quoting Philo, remarks that it was in the Temple that Pilate set up the standards at night (Proof of the Gospel 8.2.123).

Daniel R. Schwartz, “Josephus and Philo on Pontius Pilate,” in Lee I. Levine, ed., The Jerusalem Cathedra: Studies in History, Archaeology, Geography and Ethnography of the Land of Israel, vol. 3 (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Institute, 1983), pp. 182—217; Steve Mason, Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary,vol. 1B, Judean War 2 (Leiden: Brill, 2008), p. 139.

See Philo, On the Embassy to Gaius 203; Emil Schürer, Geza Vermes, Fergus Millar and Matthew Black, eds., The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1973), pp. 394—397.

Amihai Mazar, “The Aqueducts of Jerusalem,” in Yigael Yadin, ed., Jerusalem Revealed (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1975), pp. 79—80.

Louis H. Feldman, trans., Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Books XVIII—XIX, Loeb Classical Library 433 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1965), pp. 46—47.

The half-shekel Temple tax (Matthew 17:24—27) was a Pharisaic innovation on Exodus 30:12—16 that was opposed by the Sadducees (beginning of Megillat Ta’anit) and the Essenes (4Q159 f1ii.7).