022

024

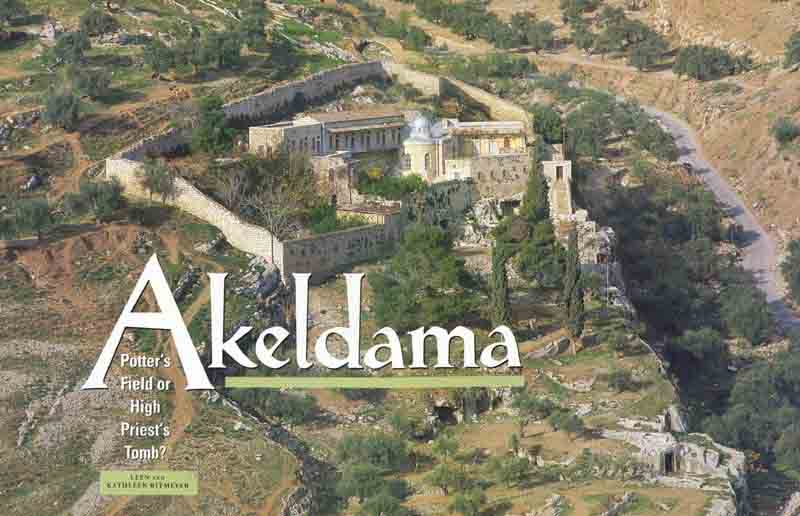

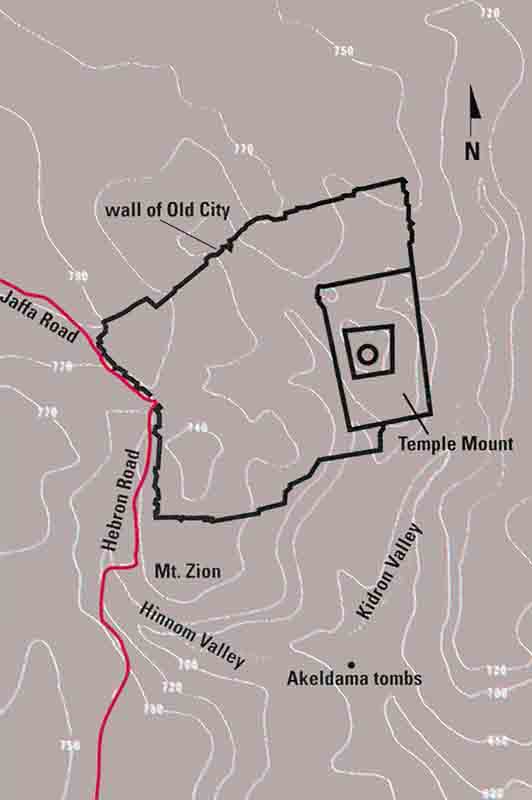

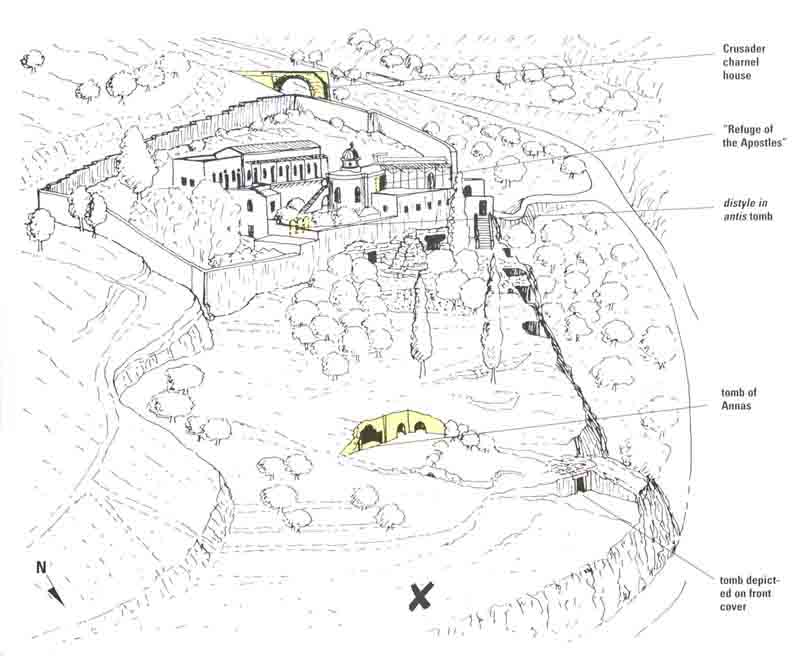

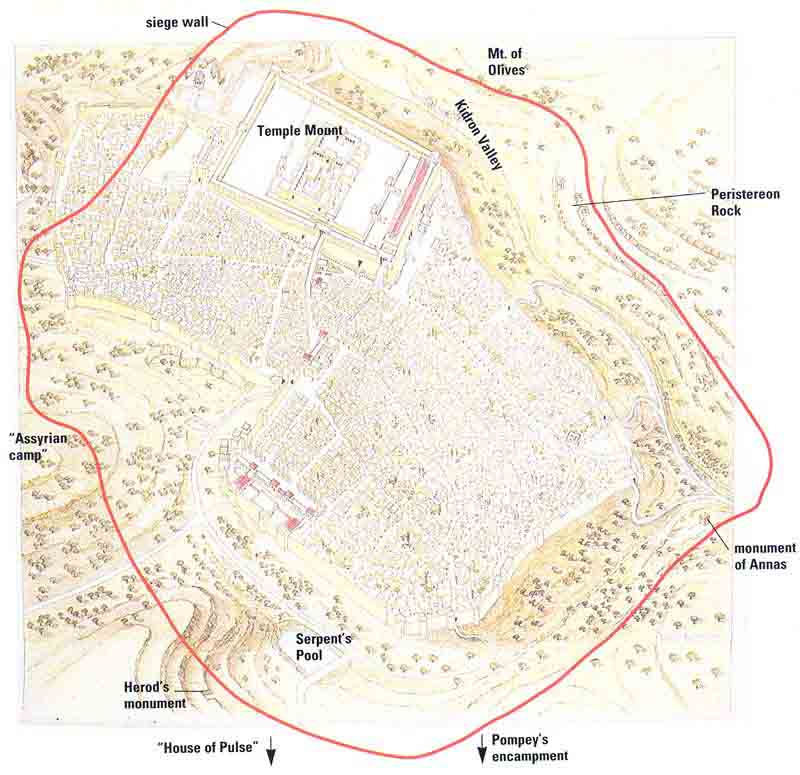

About a half mile south of the Old City of Jerusalem—at the southeast end of the Hinnom Valley, near where it joins the Kidron Valley east of the city—is one of the most impressive, important, yet largely unknown archaeological sites in the Holy Land.

Oddly, the site is not even listed in the recently published, authoritative, four-volume New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land.a Nor, so far as we can tell, is it mentioned in the 106-page encyclopedia entry on Jerusalem. Yet the area contains about 80 burial caves, most of which date to the time of Jesus, what archaeologists and other scholars refer to as the Herodian period (37 B.C.–70 A.D.). Some of these tombs are in magnificent condition, still standing to their full height.

To those who are aware of it, it is known as Akeldama, the Field of Blood, referred to both in the Gospel of Matthew and in the Acts of the Apostles.

Like many traditional attributions, however, this one too is almost surely wrong, although long-standing. Strangely, the attribution was given to an elegant tomb complex that includes the likely burial place of the family of the high priest Annas, who served in the early years of the first century A.D. Moreover, the remains that have survived two millennia can teach us a great deal about the Temple Mount, just to the north, in the days when Jesus walked on those stones.

The confusion in identification seems to have arisen from the fact that there are too many notable sites for too restricted an area. Mark Twain states the problem succinctly in his exuberant travel classic The Innocents Abroad. Describing his descent into the Hinnom Valley, Twain wrote:

“Then the guide began to give name and history to every bank and boulder we came to: ‘This was the Field of Blood; these cuttings in the rocks were shrines and temples of Moloch; here they sacrificed children; yonder is the Zion Gate; the Tyropean valley; the hill of Ophel; here is the junction of the Valley of Jehoshaphat—on your right is the Well of Job. … ’”

His plaint would meet with the heartfelt agreement of many a first-time visitor to Jerusalem:

“We are surfeited with sights. … The sights are too many. They swarm about you at every step; no single foot of ground in all Jerusalem or within its neighborhood seems to be without a stirring and important history of its own. It is a very relief to steal a walk of a hundred yards without a guide along to talk unceasingly about every stone you step upon and drag you back ages and ages to the day when it achieved celebrity.”1

In the Gospel accounts, Judas, one of the twelve disciples, goes to the chief priests and asks them what they will pay him if he identifies Jesus for them. They give him 30 pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14–16; Mark 14:10–11; Luke 22:3–6). Not long afterward, Judas fulfills his part of the bargain in Gethsemane, where he identifies Jesus with a kiss (Matthew 26:49; Mark 14:45; Luke 22:48). Jesus is immediately arrested.

According to an episode that appears only in Matthew, after Jesus is delivered to Pilate, Judas repents. He decides to return the blood money he has 025received. He brings the 30 pieces of silver back to the priests at the Temple. They refuse to take the money, however, whereupon Judas throws the 30 pieces of silver on the floor, departs and hangs himself. Since it is blood money, the priests do not put it in the Temple treasury, but use it to buy a field where strangers can be buried. It had been a potter’s field, where pottery had been manufactured. But now it is called the “Field of Blood”—Akeldama—a name that, according to the text, has survived “to this day”:

“When Judas, his betrayer, saw that Jesus was condemned, he repented and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders. He said, ‘I have sinned by betraying innocent blood.’ But they said, ‘What is that to us? See to it yourself.’ Throwing the pieces of silver in the temple, he departed; and he went and hanged himself. But the chief priests, taking the pieces of silver, said, ‘It is not lawful to put them into the treasury, since they are blood money.’ After conferring together, they used them to buy the potter’s field as a place to bury strangers [or foreigners]. For this reason that field has been called the Field of Blood to this day.” (Matthew 27:3–9).

In the Book of Acts, the apostle Peter recounts the story after Jesus has been crucified and the disciples gather in Jerusalem, where they are joined by many of the “brethren”:

“Now this man [Judas] acquired a field with the reward of his wickedness; and falling headlong, he burst open in the middle and all his bowels gushed out. This became known to all the residents of Jerusalem, so that the field was called in their language Akeldama, that is, Field of Blood” (Acts 1:18–19).

As we do not believe that Scripture contradicts itself, we understand this passage to mean that the priests used the money of Judas to acquire the field. Judas had hanged himself out of remorse (either in this field or elsewhere). Part of the structure on which he was hanging (perhaps the branch of a tree) must have broken, resulting in his falling headlong and his insides spilling out.

Akeldama, sometimes spelled Aceldama, 026Hekeldama, Hakeldama and variations thereof, is a corruption of the Hebrew aker dam, which literally means Field of Blood.

This area was identified as Akeldama as early as the third and fourth centuries. The earliest chroniclers—Eusebius, who visited the land in 335 A.D., among whose writings was a life of the Emperor Constantine, and Jerome, 400 A.D., the author of an onomasticon (a list of proper names, which sought to locate sites hallowed by Scripture)—both identify this place with confidence as the Field of Blood referred to in the New Testament. In 570 A.D., the pilgrim Antoninus made the same identification.

Arculf the “holy bishop” of Gaul, who visited Jerusalem in about 680 A.D. and who, after his shipwreck off the coast of Scotland, recounted the story of his travels to the monks who looked after him, was also in no doubt that this was indeed Akeldama. At least since this time, pilgrims who died in the Holy Land have been buried here. Arculf described the small field shown to him as Akeldama as covered with heaps of stones, where the bodies of some pilgrims were buried with care, while those of others were left to rot.

During the Byzantine period (fourth to seventh centuries), Christian monks and hermits lived here. The Universal Geography of Edrisi (Climate, III.5), written during this period, records in describing the area: “Near this are a number of houses excavated in the rock, inhabited by pious hermits.” Some of their wall paintings can still be seen in the so-called “Refuge of the Apostles.” Greek inscriptions on the outside of the many rock-cut tombs in the area also attest to their use in the Byzantine period.

The Crusaders too were certain this was Akeldama, the Field of Blood. In the 12th century, they built here a large underground vaulted structure they called Chaudemar—a corruption of Champ de Mar, the Field of Blood—that served as a charnel house, where the bones of deceased knights and pilgrims who died in the hospital of the Knights of St. John were placed to mix with the hallowed soil of Jerusalem. (Soil from the site was often taken by the shipload to consecrate cemeteries in Europe.) According to one legend, bodies lowered into this charnel house would decompose within 24 hours.

This half-ruined vaulted building still stands near the monastery that is now the principal structure on the site. The lower part of the Crusader vaulted building is rock-hewn and necessitated cutting through some of the tombs in the area.

In 1143, the Crusader Church of St. Mary was built inside one of the ancient burial caves and given to the Hospitallers of St. John. The courtyard of this church also incorporated some of the rock-cut tombs, one of which was known as the Refuge of the Apostles, which we shall describe later.

The Greek Orthodox Monastery visible today was built over this earlier church site in 1874. It is named after Onuphrius, an Egyptian anchorite famous for the length of his beard.

Because, according to Matthew, Akeldama had been a potter’s field and because the field was to be used for the burial of (presumably poor) strangers, the name Potter’s Field has become a common term for a burial ground for paupers, unknown persons and criminals. The term even appears in lowercase letters in standard dictionaries. Yet the site we are describing is a complex of tombs elaborately decorated in the style of the Herodian period.

Is it possible that a burial place with such elegant tombs would have been used for strangers?

Some who support the identification of the site as the New Testament’s Field of Blood say that this is indeed an appropriate place, because of the morbid associations attached to the Hinnom Valley, at the end 028of which Akeldama is located. The Hinnom Valley curves in an easterly direction south of Mt. Zion toward its junction with the Kidron Valley. In the book of Joshua, the Hinnom Valley is referred to both as the Valley of Ben-Hinnom—the son of Hinnom—and as the Valley of Hinnom; it marks the boundary between the territory of Benjamin in the north and Judah in the south (Joshua 15:8). The etymology of Hinnom is uncertain. Perhaps it referred to the Jebusite proprietor of the area, or some pagan deity, or it may have described a local geographical feature.

The Hinnom Valley became infamous during the First Temple period as a place where children were offered as burnt sacrifices to the pagan god Moloch. Jeremiah’s prophecy roundly denounces this practice:

“They have built the high places of Tophet, which is in the valley of Ben-Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters in the fire; which I commanded them not, neither came it into my heart. Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that it shall no more be called Tophet, not the valley of Ben-Hinnom, but the valley of slaughter; for they shall bury in Tophet, till there be no place” (Jeremiah 7:31, 32).

Thus the prophet foretells of a time at the end of days when the valley would become a place of punishment. This idea seems to have been carried over into the New Testament. Witness the words of Jesus:

“Fear not them who kill the body but are not able to kill the soul. Rather fear him who is able to destroy both soul and body in Gehenna” (Matthew 10:28).

Gehenna is an Aramaic word now found in English dictionaries. It is a contraction of the Hebrew gei hinnom, the Valley of Hinnom, and means hell or any other place of continuing misery.2 Is it possible that this part of the Hinnom Valley was identified as Akeldama, the Field of Blood, due to these evil associations?

Another effort to make the connection between this site and the Field of Blood examines Akeldama’s possible previous use as a potter’s field, a place where pottery was made.

In ancient times, pottery workshops were generally located in a specific area outside the city. According to the Talmud, because of the smoke they created, potteries were forbidden within the city of Jerusalem.3 So it is possible this was once a potter’s field, although there were no renowned clay deposits in the southeast end of the Hinnom Valley.

Some who believe this site was a potter’s field point to a dip in the patch of ground next to the Crusader’s 029charnel house as an indication that clay was removed from the site. This dip was formed, however, as a result of extensive quarrying, carried out centuries before the Second Temple period, not by the removal of clay, as a visit to the site will confirm.4

Perhaps the strongest support for the identification of this site as the Field of Blood comes from imaginary, often dramatic, descriptions of what occurred there, like this one:

“Out [Judas] rushed from the Temple, out of Jerusalem, into solitude. Whither shall it be? Down into the horrible solitude of the Valley of Hinnom, the Tophetb of old, with its ghastly memories, the Gehenna of the future, with its ghostly associations. But it was not solitude, for it seemed now peopled with figures, faces, sounds. Across the valley, and up the steep sides of the mountain! We are now on the potter’s field … somewhat to the west above where 031the Kidron and Hinnom valleys merge. It is cold, soft clayey soil, where the footsteps slip, or are held in clammy bonds. Here jagged rocks rise perpendicularly: Perhaps there was some gnarled, bent, stunted tree. Up there he climbed to the top of that rock. Now slowly and deliberately he unwound the long girdle that held his garment. It was the girdle in which he had carried those thirty pieces of silver. He was now quite calm and collected. With that girdle he will hang himself on that tree close by, and when he has fastened it, he will throw himself off from that jagged rock.”5

The most damaging fact—one that makes it implausible to connect this site with the Field of Blood—is that here are some of the most splendid Herodian tombs ever discovered. It is not a Field of Blood, but a field of elegant and elegantly decorated burial caves. One of them probably belonged to the high priest Annas, who held office from 6–15 A.D. Is it likely that a cemetery for strangers would displace a Jewish cemetery for wealthy and priestly families? Would a prime piece of real estate so close to the city be purchased for burying strangers?

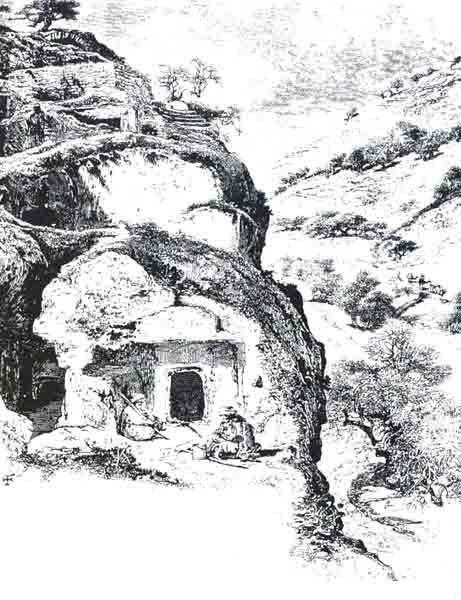

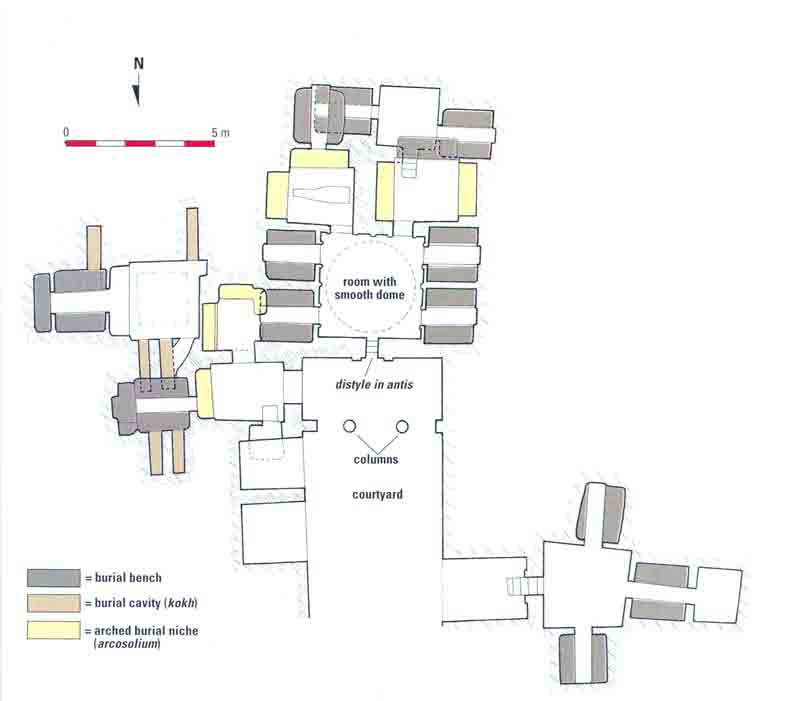

Two of the most important tombs are now incorporated into the Monastery of St. Onuphrius. One is in the chapel of the monastery and is known as the “Refuge [or Retreat] of the Apostles.” According to tradition, the disciples themselves hid here following the capture of Jesus at Gethsemane (Matthew 26:56; Mark 14:50). The cave has been altered somewhat to accommodate the chapel. But both the back and the side rooms of the chapel/tomb have loculi (kokhim in Hebrew; singular kokh) in the walls: that is, horizontal holes about 2 feet wide, 2.5 feet high and 6 feet long, in which bodies were laid. These kokhim are typical of Second Temple-period tombs.

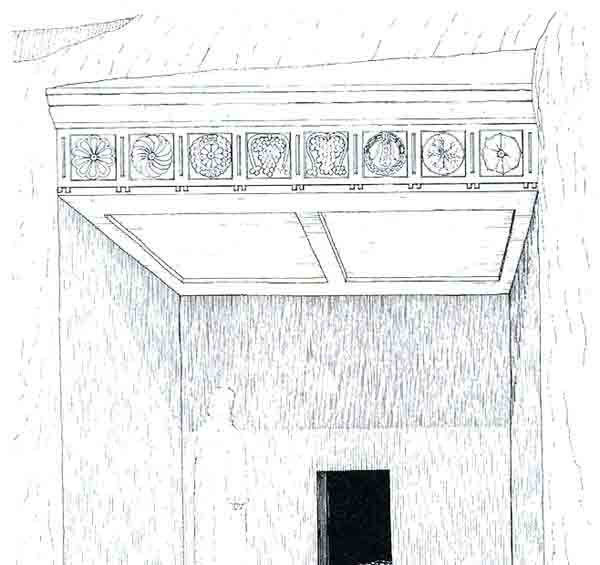

The tomb was entered through a portico or entrance chamber cut into what was originally the side of the rock. The outer side of this entrance chamber was entirely open. Such a portico is a common feature of the most elegant tombs of the period. Sometimes these porticoes have two or more columns that appear to support the rock ceiling on the open side. When a portico has these two columns, it is known as distyle in antis (“two-pillared porch”). The portico of the “Refuge of the Apostles” does not have these columns. Other tombs in the area, as we shall see, do.

This portico does have, however, one outstanding feature—a beautiful Roman Doric frieze over it. Only the most elaborate tombs of this period had decorated porticoes. This tomb must therefore have belonged to someone of immense wealth.

A Roman Doric frieze consists of a series of triglyphs (protruding vertical lines) with spaces between. In the “Refuge of the Apostles,” the engraver used diglyphs instead of the usual triglyphs, apparently because of lack of space. But this is not what distinguishes the “Refuge of the Apostles” from other elegant Jerusalem tombs.

033

The spaces between the triglyphs (or diglyphs) are known as metopes. In Jerusalem friezes, as elsewhere, the metopes are sometimes empty, and sometimes filled with relief carvings. In the famous tomb of Bene Hezir in the Kidron Valley, the metopes are blank. In the so-called Tomb of Absalom, adjacent to the tomb of Bene Hezir, the metopes are filled with circular discs. The metopes in the frieze of another famous Jerusalem tomb (known as the Cave of Um el-’Amed) are filled with identical rosettes. What fills the metopes in this frieze, however, makes it perhaps the most interesting of the Doric friezes among Jerusalem’s funerary monuments.

The eight metopes of the frieze from the Refuge of the Apostles have survived. The two central metopes have grape bunches. The other metopes are filled with rosettes of varying patterns. The interesting point is that the decorations in these metopes vary from one another, making it unique among all the elaborate Herodian tombs in Jerusalem.

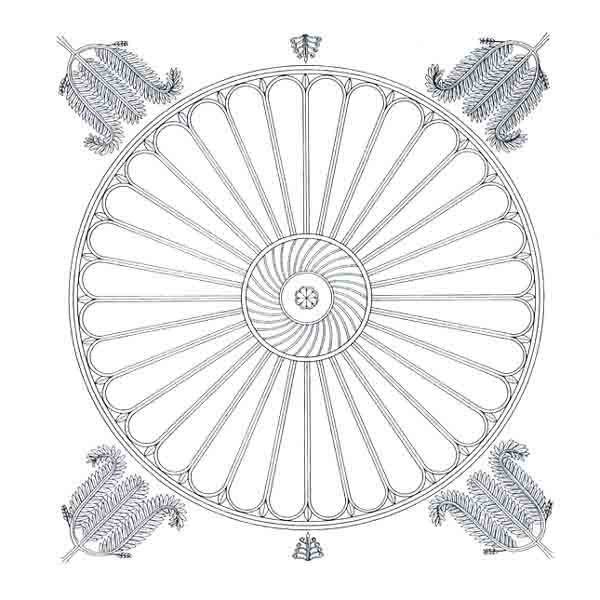

We emphasize this because we believe this same variation was repeated in the contemporaneous friezes of the Temple Mount. In the course of the excavations south of the Temple Mount, a few hundred meters away, fragments of numerous rosettes were found that may well have belonged to friezes on the Mount itself. These fragments differ from one another, however, in design, size and complexity. Some rosettes have separate leaves; others have complex concentric sets of leaves.

There is still more evidence behind the “Double Gate” on the southern wall of the Temple Mount, in underground passageways that once led up to the Herodian Temple Mount. Four original Herodian domes in this passageway, unfortunately not open to the public, have survived. Like the frieze in the Refuge of the Apostles, the in situ domes behind the Double Gate are decorated with bunches of grapes. (The frieze on the so-called “Tomb of the Kings”—actually the tomb of Queen Helena—north of Jerusalem, also has a bunch of grapes in the center.) In short, it appears that the designers of the tomb known as the Refuge of the Apostles were using the Temple Mount friezes as a model.

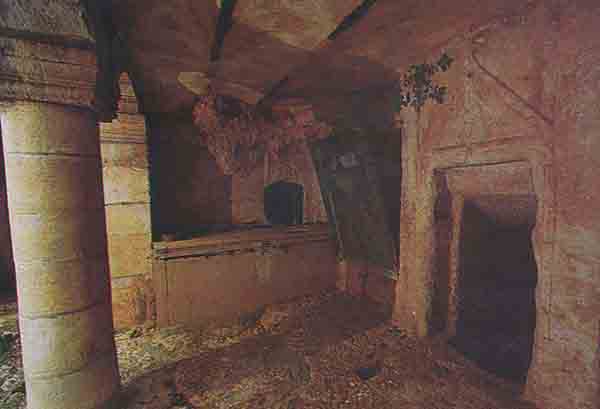

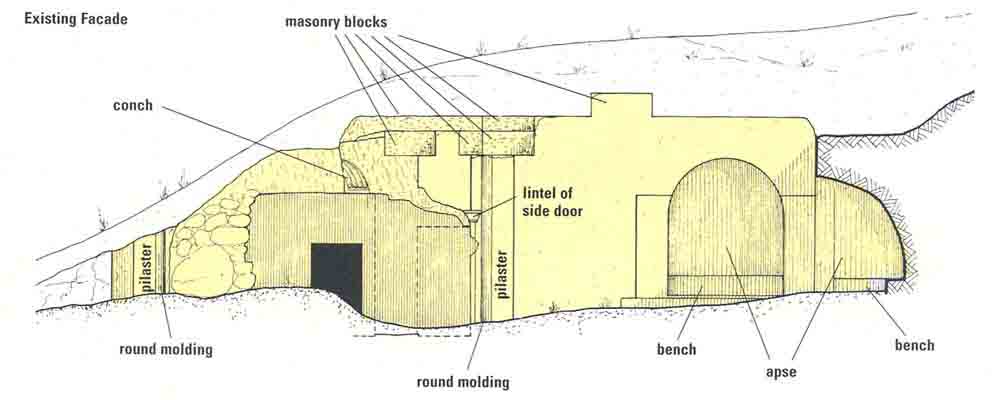

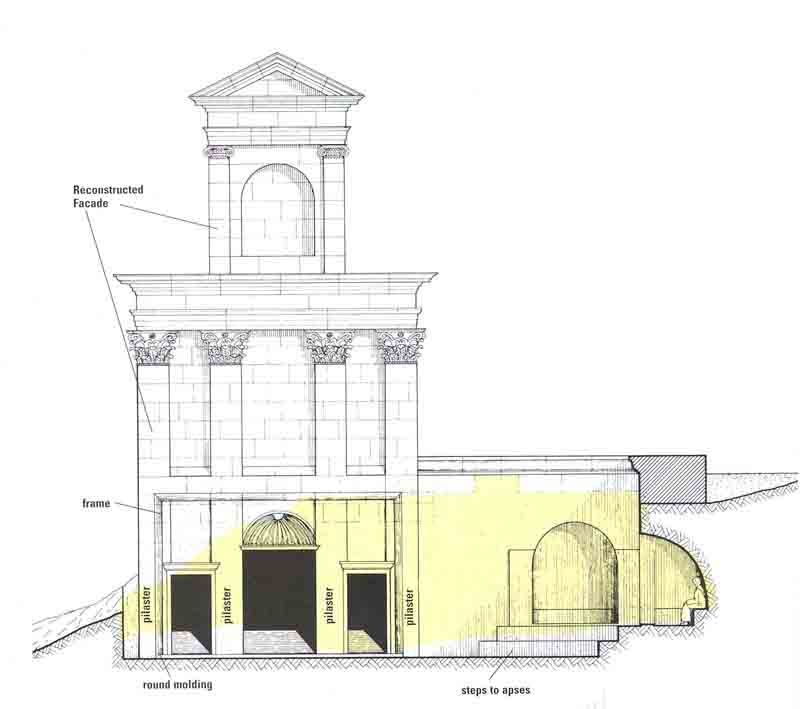

Another important tomb in Akeldama is located in the substructures of St. Onuphrius’s Monastery. It is reached by a flight of steps that descends from the modern-day courtyard of the monastery. This tomb also has a portico, but it differs from the portico in the Refuge of the Apostles in that here the portico is supported by two columns (distyle in antis). Like the typical distyle in antis, this portico has engaged half-columns attached to the side walls (forming pilasters 034instead of columns) in a row with the columns. Behind the portico is the main chamber of the tomb, with an undecorated or smooth dome ceiling. The entrance from the portico to this chamber is by an Attic doorc with a high pediment—leaving no question that this is a Second Temple-period tomb. Two other rooms lead from this main chamber. In these rooms, burial benches line the walls. In the First Temple period, bodies were laid out on stone burial benches instead of in kokhim. These benches indicate that the tomb originated in the First Temple period, but was adapted and re-used in the Second Temple period.

One of these side chambers with First-Temple period burial benches leads into an elaborate system of five tomb chambers with kokhim. In this way, too, the First Temple-period tomb was re-used and extended in the Second Temple period.

Although the two columns in the portico (creating the distyle in antis) have survived, three modern arches have been carved above the columns, apparently when 035the tomb was incorporated into the monastery. The slanted pilaster capital on the right (west) indicates that this portal once also had a triple-arched entrance. The original arches would most likely have been semi-circular.

A portico supported by two columns resembles a triple gate. At least two gates to the Temple Mount were of this design; both the gate over Robinson’s Arch and the gate over Wilson’s Arch have been reconstructed as distyle in antis,d although these gates had no arches. It is possible that other gates on the Temple Mount had arched triple gateways. Apparently this magnificent Second Temple tomb was also designed and decorated to reflect the architecture of the nearby Temple Mount, easily visible from the slopes of the Hinnom Valley.

The late Professor Nachman Avigad, with whom Leen had the privilege to work, once wrote that the ornamental architecture of Herod’s Temple represents “a blank chapter.”6 This is no longer so. A comparative study of the ornamentation of nearby tomb architecture can illuminate the architecture and design of the Temple Mount, as well. Such a comparative study can only be completed, however, after all the decorative elements from the Temple Mount excavations are published. Unfortunately, this may never happen. The Temple Mount excavations were conducted from 1968 to 1978 under the direction of Professor Benjamin Mazar of Hebrew University, with Meir Ben-Dov as field director. Only two preliminary reports have been published since then and no one is working on the publication of the Second Temple period remains.

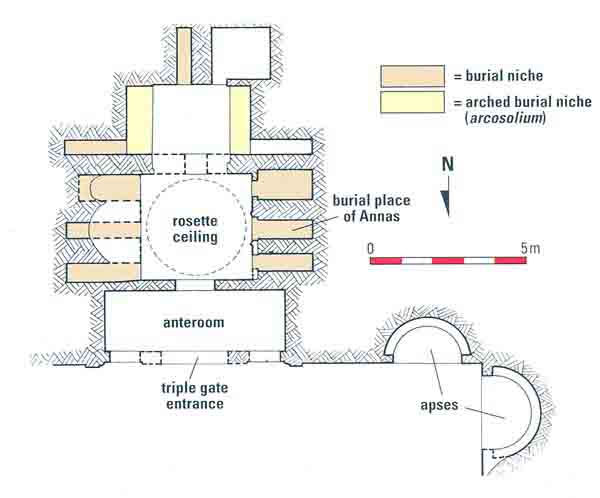

The Akeldama tomb with the most interesting and unusual decoration is located outside the monastery on a terrace below it. It originally had a triple-gated entrance that resembled the triple gate in the southern wall of the Temple Mount. Unfortunately, little is left of the entrance to this tomb, but enough remains to reconstruct its original appearance. A semi-hemispherical shell design sat over the middle of the three entrances to the portico of the tomb cave. Engaged half-pillars were at either end of the entrance facade.

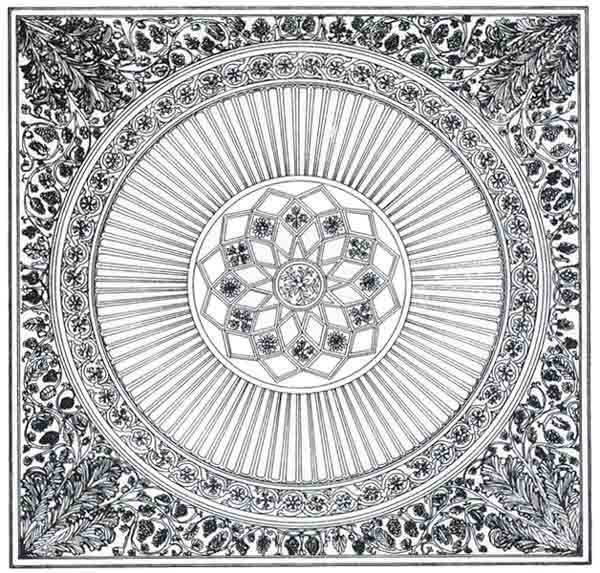

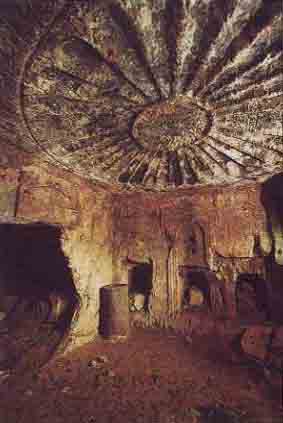

Inside the tomb, the principal chamber has an intact and magnificently decorated domed ceiling. The central feature of the dome is a deeply carved rosette of 32 petals, grouped around a whorl rosette of light petals 076that can still be faintly detected. Stylized acanthus leaves fill the four corners of the domed ceiling. The huge rosette on this domed ceiling and the decoration around it distinguishes this tomb from all other Second Temple tombs in Jerusalem. Indeed, none of the other tombs have such sculpted internal decoration. The only exception is a small rosette on the ceiling of the burial room of the so-called “Tomb of Absalom.”

In the underground passage behind the Double Gate leading up to the Temple Mount are four intact Herodian domes, as previously mentioned. One of these domes closely resembles the decorated dome of this tomb. Although the dome in the Double Gate passageway is even more elaborately decorated and still larger, the principal decoration is similar. It too features a multi-petalled rosette in the center of which is a small rosette. As in our Akeldama tomb, acanthus leaves fill the four corners of the dome. Apparently the decoration in the dome of this tomb was modeled on the decoration of a dome in the Double Gate passageway.

Grouped around this tomb are six other finely decorated tombs, some with Attic door frames and plain domed ceilings, although none of the tombs is as lavish as the one we have just described.

We believe the most lavishly decorated tomb, in the midst of the other six tombs, in imitation of the decoration on the nearby Temple Mount, was the tomb of the high priest Annas (6–15 A.D.) and his family. In his account of the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., the first-century Jewish historian Josephus describes the siege-wall the Roman commander Titus built around the entire city to prevent the Jews from escaping. In the course of his description of the part of the wall south of the city, Josephus tells us that one part of it “ascended over against the tomb [the Greek says monument] of Ananus [Annas] the high priest,”7 precisely at the site we know as Akeldama. If Annas’s tomb is here—and the site, according to Josephus’s description, was well known because Annas’s tomb was here—it would most likely be the most elaborate tomb in the tomb complex. The fact that the facade of this central or “Triple Gate” tomb continued upward in masonry would indicate that it once had an upper part, now destroyed. Possessed of such a superstructure, it would of course be much more prominent than the adjacent tombs, easily seen from afar and worthy of mention by Josephus as a landmark in his description of the siege-wall.

According to Josephus, Annas’s five sons also served as high priest:

“It is said that the elder Ananus [Annas] was very fortunate. For he had five sons, all of whom, after he himself had previously enjoyed the office for a very long period, became high priests of God—a thing that had never happened to any other of our high priests.”8

If we are correct that the highly decorated tomb that, for want of a better name, we shall call the central or “Triple Gate” tomb, is that of Annas, the tombs around it may be those of his sons. Annas’s sons were later succeeded by Annas’s son-in-law, none other than Caiaphas, who served from 18 to 37 A.D. According to the Gospels, Caiaphas presided at the trial of Jesus (Matthew 26:57). His family tomb has recently been found nearby and is identified by an ossuary, or bone box, engraved with his name.e

A few meters west of the facade of this tomb are two apses at right angles carved in the rock that have benches running around the inside, obviously meant to be used for sitting. Perhaps visitors to the tomb rested here, or, alternatively, the benches may have been used by people guarding the tomb.

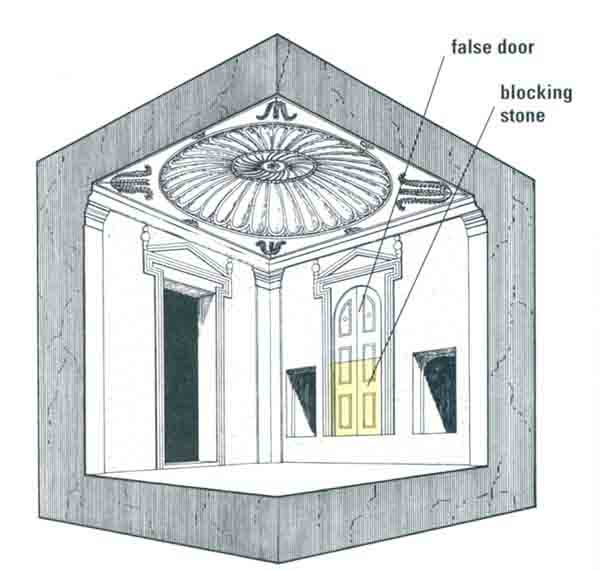

Inside the tomb, one loculus (kokh) stands out. It is between two other loculi on the western wall, to the right as we enter. Around and above this middle kokh is a beautifully carved Attic-style doorway with a pediment above it—a false door because it simply frames the loculus at the bottom of it. 078When a body was interred in the loculus, it would have been sealed with a blocking stone. This was probably the loculus in which the body of Annas was laid. (Incidentally, a small fragment of an Attic doorframe was excavated below Robinson’s Arch, additional evidence that the decorative elements of these tombs were copied from the Temple Mount.)

On the opposite wall of the main chamber of this tomb (to the left as we enter), are three more loculi. In a later period, an apse was carved into this wall—perhaps a chapel for a hermit or monk. This is a relatively small tomb with only two burial chambers and not more than nine kokhim. What it lacks in size, however, it makes up in splendor.

Whether or not this tomb once held the body of the high priest Annas, it seems hardly likely that this exquisitely decorated tomb complex, full of some of the choicest and most expensive burial sites in all Jerusalem, in close proximity to the city and the Temple Mount, would have been used as a burial plot for impoverished strangers.9 It is still called the Field of Blood—Akeldama—but this must now be regarded as a traditional, not an authentic, designation.

About a half mile south of the Old City of Jerusalem—at the southeast end of the Hinnom Valley, near where it joins the Kidron Valley east of the city—is one of the most impressive, important, yet largely unknown archaeological sites in the Holy Land. Oddly, the site is not even listed in the recently published, authoritative, four-volume New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land.a Nor, so far as we can tell, is it mentioned in the 106-page encyclopedia entry on Jerusalem. Yet the area contains about 80 burial caves, most of which date to the time […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Archaeological Encyclopedia for the ‘90s,” BAR 19:06.

An Attic door is bordered by a grooved, rectangular molding, and the lintel extends beyond the jamb. For a drawing, see Kathleen and Leen Ritmeyer’s “Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem,” BAR 15:06.

Kathleen and Leen Ritmeyer, “Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount,” BAR 15:06.

See Zvi Greenhut, “Burial Cave of the Caiaphas Family,” BAR 18:05. See also Ronny Reich, “Caiaphas Name Inscribed on Bone Boxes,” BAR 18:05.

Endnotes

The metaphor is said to have been derived from the fact that the valley was used as a dump for the city’s rubbish and, as a consequence, fires were continually burning there. We cannot find any reference in the Mishnah to support this assertion. However, that the association between the Valley of Hinnom and the underworld was not merely a Christian one is made clear from early Rabbinic writings from the early Christian era, such as: “The disciples of Balaam, the wicked, inherit Gehenna and go down to the pit of destruction, as it is written: ‘The shameless are for Gehenna and the shamefast for the garden of Eden’” (Mishnah, Avot 5:19, 20).

Charles Wilson in Notes on the Survey, and on some of the most remarkable localities and buildings in and about Jerusalem 1865 (facsimile edition, Jerusalem: Ariel, 1980), p. 68, mentions that quarrying was still taking place on the site.

Alfred Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1967), vol. 2, p. 575.

Claude R. Conder in Warren and Conder, Survey of Western Palestine, Jerusalem (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1884), p. 419, and The City of Jerusalem (London: Murray, 1909), pp. 23, 184, 325, as well as Gustaf Dalman, Sacred Sites and Ways (London: S.P.C.K., 1935), prefer to identify the “Refuge of the Apostles” tomb as that of Annas himself, but the central or “Triple Gate” tomb was clearly more impressive. Furthermore, the latter tomb shows clear indications that it originally had a superstructure, while the Refuge of the Apostles had an undecorated band of bedrock above its frieze, which would preclude it from ever having had a superstructure. It could thus never have been a monument.