Raider of the Lost Mountain—An Israeli Archaeologist Looks at the Most Recent Attempt to Locate Mt. Sinai

046

In an article entitled “Has Mt. Sinai Been Found?” BAR 11:04, Italian archaeologist and author of the popular, though now out-dated Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Knopf, 1963), Emmanuel Anati argues that he has found Mt. Sinai, the Mountain of God, on a ridge in the western edge of the Negev Highlands, four miles from the Egyptian border. He has now expanded his argument in an oversize, colorful and expensive book called The Mountain of God (New York: Rizzoli, 1986).

Anati’s search for Mt. Sinai, as presented in The Mountain of the God, is an anachronistic vestige from the 19th century. The only difference is that Anati’s book is illustrated with beautiful color pictures. The academic community—archaeologists and Biblical scholars alike—will, you may be sure, ignore this new revelation. The problem, however, is that many lay people with a genuine interest in the Bible and Biblical archaeology will be vulnerable to this kind of material, especially because the author is relatively well known, his subject matter is magnetic and his presentation is beautiful.

To review a work like this is, in a way, a disgraceful task. But it is important to do—both to save the trampled honor of archaeology as a serious scientific discipline and to protect the innocent mind of the lay public from these kinds of theories.

The search for Mt. Sinai, the Mountain of God, was a popular quest in the 19th century, when travelers and explorers roamed the Sinai Peninsula looking for footsteps of the Children of Israel. However, decades of research, even by great scholars like Edward Palmer and Edward Robinson, made little, if any, progress. Finally, in about the 1920s, the question was laid to rest. The simple reason was that not a shred of evidence was found that cast any light on the Biblical Exodus narratives.

The present state of research on the Exodus can be summarized as follows:

The only source that provides any direct evidence concerning the Exodus and the desert wanderings of the Children of Israel is the Bible. There is not a single direct reference for these Biblically described events in the rich Egyptian material, although an abundance of documents from the 19th Egyptian dynasty do reflect the general conditions that prevailed in the eastern Nile Delta at the time most scholars would date the reality behind the Exodus narratives. Nor is there any real archaeological evidence concerning the Biblical narrative in Sinai or the Negev.

The Bible refers to numerous place-names—toponyms is the scholars’ word—on the route of the Exodus. Of all these toponyms mentioned in connection with the Israelites’ desert wanderings only two can be securely identified—Kadesh-Barnea (Ein el-Qudeirat in the eastern part of north Sinai) and Ezion-Geber (Tell el-Kheleifeh near present-day Eilat). A few other places—Pi-hahiroth, Baal-zephon and Migdol (see Exodus 14 and Numbers 33)—may be located in the northeastern corner of the ancient Nile Delta (present-day northwestern Sinai). However, of the other numerous toponyms, none can be located.

Three factors determine the identification of Biblical (or any other ancient) sites: (1) the geographical context of the Biblical reference, (2) the archaeological finds at the proposed site (that is, whether the proposed site was occupied in the particular period when it appears in the text), and (3) the possible preservation, in some form, of the ancient toponym in a later, even modern, name. None of these factors is present in the dozens of desert-stations on the Exodus route. From the Bible itself, there is absolutely no way to determine in what part of the southern deserts extending from the Negev to the southern tip of Sinai these sites are located. Nor do any archaeological finds in Sinai help to identify any of these sites. (Admittedly, one can claim that the Israelites were nomads and hence did not leave behind any remains.) Finally, we cannot rely on later or modern desert place-names to provide any help (as we do in settled areas) because there was no continuity of occupation in the desert. Thus, the proposed identification of Biblical Hazeroth, for example, with Ein 047Huderah, southwest of Eilat, is a mere desert mirage; dozens of sites in Sinai resemble this ancient toponym—Ein el-Ahdar, Wadi Ahdar, etc.

Moreover, we must not ignore the fact that the Biblical material was assembled centuries after the supposed events took place. Without denigrating the importance of the Exodus narratives for the faith of ancient Israel, we simply cannot treat these Biblical narratives as straightforward history. We must understand the historical and religious background against which these traditions crystallized at a later date, during the period of the Israelite monarchy, hundreds of years after the supposed events that the narratives describe could have taken place.

For all these reasons, the day when explorers rushed to the desert with the Bible in one hand and a spade in the other is long gone. In fact, the only “historical” tradition about Mt. Sinai dates from the Byzantine period, in the fourth to seventh centuries A.D., at a time when a host of holy places in southern Sinai and elsewhere were “identified.” At that time the location of Mt. Sinai crystallized near St. Catherine’s monastery. But this identification must be evaluated against the background of the events in the eastern provinces of the Roman world in the second to fourth centuries, as well as against the environmental aspects of the region.

Taking all these factors into consideration, it is not surprising that we know no more about the Exodus and the desert wanderings of the Israelites now than we did 150 years ago.

Until new archaeological materials are found, however—an extremely unlikely possibility—no serious archaeological research on the Exodus and the desert wanderings can be carried out.

It is therefore regrettable that once again we are witness to a romantic expedition exploring the southern wilderness, choosing a peak that has not previously been a candidate, and then trying to convince lay people that Mt. Sinai has been found. Unfortunately, some gullible members of the lay public are always ready to accept simple deus-ex-machina solutions, rather than undertaking the painful struggle required to deal with a complex problem that has no clear-cut answer.

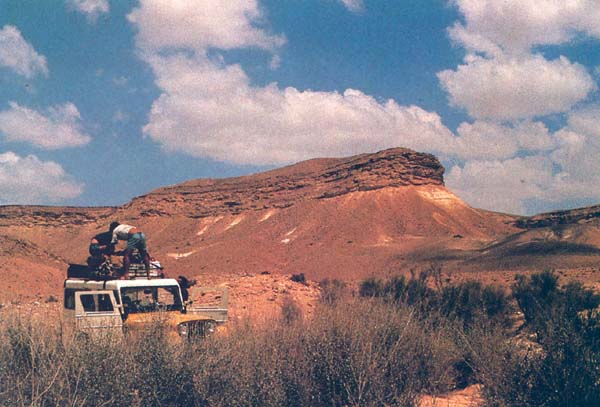

Anati’s candidate for the Mountain of God is Har Karkom, a flat ridge surrounded by cliffs on the southwestern edge of the Negev Highlands. His evidence is that on the ridge and around it are a large number of small sites dating to the third millennium B.C., as well as an impressive concentration of rock drawings. Anati interprets some of these sites as a 048temple and a sacred group of twelve stones, etc. He understands some of the rock drawings as depicting cultic scenes. He then attempts to fit the Biblical descriptions into this setting.

This is not really difficult to do. The Biblical material can be used almost anywhere in the south: in the Negev, near St. Catherine’s monastery in Sinai, in northern Sinai, in northwestern Sinai near the Gulf of Suez, etc.

Let us look at Anati’s archaeological “evidence” that supposedly supports his conclusion. (I do not intend to comment on his treatment of the Biblical material; Anati is, after all, an archaeologist, not a Biblical scholar. But there is another reason why it is unnecessary to comment on the way Anati handles the Biblical materials: Once we expose the false archaeological evidence, his whole theory collapses.)

At the outset, Anati must confront a “minor” chronological problem: The emergence of Israel in Canaan occurred in the 13th–12th centuries B.C. But Anati dates his sites around Har Karkom almost 1,500 years earlier than that. The date for the emergence of Israel in Canaan has been fixed by data accumulated from a host of excavations and surveys conducted throughout the country since the 1920s, and is now so well established that it cannot be successfully challenged. This date is also supported by the earliest extra-Biblical reference to Israel—in the famous Merneptah stele, a hieroglyphic inscription that dates to the year 1207 B.C.

Because Anati dates his sites near Har Karkom to the third millennium B.C., he must conclude that the Sinai narratives in the Bible reflect a third millennium tradition. But he nowhere explains how this third millennium tradition survived until the first millennium B.C. in the memory of people in Jerusalem (where the material was compiled), without any continuity of activity at Har Karkom!

A word of caution should also be noted about the large number of sites Anati has supposedly found at Har Karkom. In arid zones, sites tend to spread over vast areas. How many sites there actually are depends on how you count them. I suspect that at Har Karkom there are no more than a few dozen real sites, plus a large number of rock drawings.

Moreover, the concentration of these sites near Har Karkom is by no means unique. Similar clusters of sites can be found in other parts of the Negev. Indeed, the density of sites per square mile is much higher in other areas of the Negev Highlands than at Har Karkom.

Anati fails to mention the fact that sites from the Early Bronze Age II (c. 2850–2650 B.C.) have been found throughout the southern deserts—from Arad in the north to southern Sinai in the south. Nor does he mention the fact that sites from the Intermediate Bronze Agea (c. 2350–2200 B.C.) are found all over the Negev Highlands. The sites near Har Karkom are 049therefore part of a broader archaeological-historical phenomenon. Anati refers to none of the important works published by Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Rudolph Cohen and William Dever that describe this phenomenon and the results of intensive research conducted in Sinai and the Negev in recent years. Nor does Anati refer to the extensive surveys and rescue excavations conducted in the Negev by the Israel Department of Antiquities and the Archaeological Survey of Israel since 1979. In short, Anati deals with the sites at Har Karkom as if they were the only sites in the whole area with evidence of human activity; he ignores the entire archaeological context of the Har Karkom phenomenon.

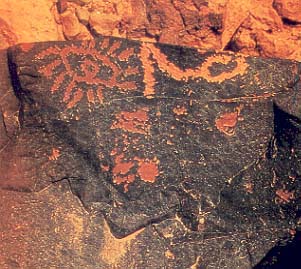

Next: In my view, it is extremely tricky, probably impossible, to date rock drawings accurately.b Most of the scenes depict daily life of the desert people—herding of flocks, hunting, etc. It is difficult, if not impossible, to compare such scenes to securely dated material. Dating by the patina is also baseless. The patina does not provide a reliable dating mechanism because the production of the patina depends on factors other than age, such as microclimate, etc. The most reasonable assumption is that these rock drawings were carved by local pastoral nomads over a long time, rather than in only one archaeological period.

Anati tells us that Har Karkom was occupied in some periods, separated by periods of “hiatus” when there was no occupation. This reflects an outmoded, naive view of the history of the occupation of the southern deserts. Sinai and the Negev are not like certain areas in Saudi Arabia or the Sahara, where the harsh environment either prevents human occupation or makes it extremely difficult. Ecological niches in the Negev Highlands and the high mountains of southern Sinai, as well as other parts of the region, readily permit human activity, based on pastoral nomadism, hunting and seasonal agriculture. Accordingly people lived here continuously, but unlike areas of settled occupation, they rarely left any archaeological remains. The exceptions are the few periods when the desert inhabitants built stone structures. The question of why they did so at certain times and not at others is beyond 050the scope of this article. But the point here is that there were no periods without human occupation and that the rock art at Har Karkom may represent human activity from periods without other archaeological remains.

The chronological term that Anati uses, BAC (Bronze Age Complex), to cover both Early Bronze Age and Intermediate Bronze Age sites is misleading: Early Bronze sites and Intermediate Bronze sites can be distinguished from one another in a scientific excavation and even in surveys in most cases, when done by trained archaeologists.

Anati’s interpretations of some of the finds (and in a few cases, these are not archaeological finds at all, but “innocent” natural phenomena) belong to the world of faith, rather than the world of archaeology: According to Anati, broken stone slabs represent the tradition of the stone tablets Moses received on Mt. Sinai. Sites around the Har Karkom ridge are interpreted as the encampments of the Israelites. Rock drawings depict “the serpent” and “the staff” in the tradition of the Bible. Other rock drawings, he says, depict standing stones and other “Biblical” scenes. The truth is that all this is in the eye of the beholder.

Anati also mistreats toponyms. Two examples will suffice. He identifies Biblical Hormah with Nessana, a Nabatean-Byzantine site with absolutely no earlier material. He uses names like Paran and Zin for areas near Har Karkorn without any discussion of the problem of their location.

To sum up, this book reflects not a trace of the elementary skills required by the scientific discipline of archaeology. Anati fails to distinguish between (1) finds, (2) the interpretation of these finds, and (3) a synthesis of the finds with the historical source (in this case the Bible).

Now let us turn from Anati’s heavenly theories to an earthly discussion; that is, to a rational explanation of the Har Karkom finds.

After eliminating the far-fetched interpretations and the misleading information, we are left with some real facts: Here is a ridge in the Negev with more human occupation sites than the immediately neighboring ridges. In addition, Har Karkom differs from the main parts of the Negev Highlands by having a much larger number of rock drawings than at other sites.

How can we explain this overall phenomenon?

The answer lies in the patterns of pastoral existence found in the Negev Highlands, as well as in certain parts of central and southern Sinai—a kind of pastoral existence still reflected in subsistence patterns of 20th-century Bedouin. The ecology of these environments requires short-distance, seasonal migrations. There is, in effect, a seasonal vertical movement, from the lower regions in winter to the higher ecological niches in summer. Higher elevations get more precipitation and hence provide more pasturage for flocks. In the winter the sheep/goat pastoral nomads would exploit the pastures in the lower areas, which sprout earlier because of their warmer temperatures. In the spring these pastoral nomads would move to the higher regions. In the western part of the Negev Highlands, the winter-pasture areas were to the west, in the plains of northwestern Sinai. In the summer the flocks were taken eastwards, to the ridges of Har Horesha, Har Harif, Har Loz, Har Ha-mecara, Har Saggi—and Har Karkom. This is the reason for the large concentration of sites along this line. Har Karkom had a special advantage nearby well (Be’er Karkom) that supplied water for the flocks. (This, by the way, explains why most of the sites Anati found are scattered west of Har Karkom). The water source of Ein Ha-mecara played a similar role further north. The explanation for the relatively large number of rock drawings at Har Karkom should also be sought in the pastoral/nomadic way of life: The fact that the ridge is surrounded by steep cliffs probably made it more attractive to the herders because they could control the flocks more easily. As they whiled away their time at this popular site, they made their drawings on the rock faces.

To return for a moment to the Mountain of God: The importance of the Biblical narrative lies in its moral code and in the role it played in Israel’s development and in the tradition of Western civilization. The Biblical account was never meant to be a guide to enthusiastic archaeological expeditions. Let us leave the Mountain of God to rest in peace. For those who cannot resist temptation, let Indiana Jones deliver the goods.

In an article entitled “Has Mt. Sinai Been Found?” BAR 11:04, Italian archaeologist and author of the popular, though now out-dated Palestine Before the Hebrews (New York: Knopf, 1963), Emmanuel Anati argues that he has found Mt. Sinai, the Mountain of God, on a ridge in the western edge of the Negev Highlands, four miles from the Egyptian border. He has now expanded his argument in an oversize, colorful and expensive book called The Mountain of God (New York: Rizzoli, 1986). Anati’s search for Mt. Sinai, as presented in The Mountain of the God, is an anachronistic vestige from […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

This archaeological period is also referred to by some archaeologists as Early Bronze IV and by others as Middle Bronze I. Unfortunately, the terminology has not yet been standardized.

See also the letter of Professor Albert Jamme of The Catholic University of America in Queries & Comments, BAR 11:06.