Recollections from 40 Years Ago: More Scrolls Lie Buried

051

With so much public attention lately focused on the Dead Sea Scrolls, the question is frequently asked, with increasing insistence: Are there more scrolls—either undiscovered in the caves or in the hands of the Bedouin or of those who acquired them from the Bedouin? This article will suggest that the answer is yes on both counts.

My story begins exactly 40 years ago—in 1953—when I, an Israeli kibbutznik imbued with a love of my people’s past, joined an archaeological team led by the late Yohanan Aharoni to explore some caves in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea.

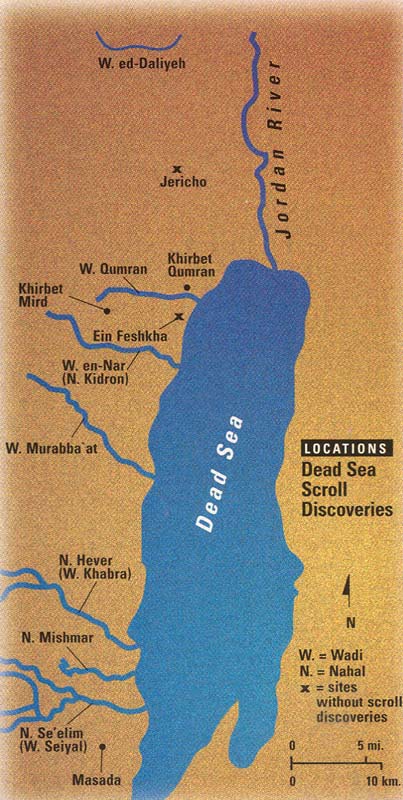

In 1947 Ta‘amireh Bedouin had discovered the first of the now-famous Dead Sea Scroll caves in the vicinity of the Wadi Qumran. Once the Bedouin realized the financial rewards that could be realized from scroll materials, many of them turned from shepherding to cave exploring. In 1951 the Bedouin again hit paydirt, so to speak. They found more scrolls and other documents, albeit all fragmentary, in the Wadi Murabba‘at, the wadi, or canyon, just south of the Wadi Qumran.

Both the Wadi Qumran and the Wadi Murabba‘at were in territory then controlled by Jordan (now referred to as the West Bank). The Israeli border lay barely five miles south of the Wadi Murabba‘at. This border, however, was no barrier to the Bedouin; they would regularly cross it with ease. In the summer of 1952, additional scrolls came on the antiquities market that supposedly had come from an “unknown source,” but it was widely rumored that they came from caves within Israel. The Israel Department of Antiquities (now the Israel Antiquities Authority) quickly organized a survey of the area just south of the border, in the Judean desert, led by Aharoni, then an inspector for the department and later one of Israel’s most distinguished archaeologists.

I was a member of this team. From November 25 to December 16, 1953, we surveyed, among others, the Nahal Hever (nahal is the Hebrew for the Arabic wadi), from where these fragmentary texts from an “unknown source” had been rumored to have come.

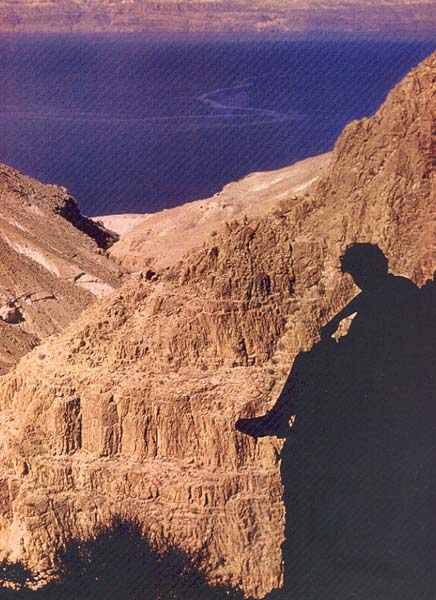

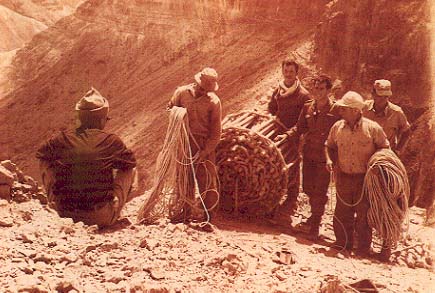

In this area the cliffs rise about 1,500 feet above the Dead Sea, cut only by the wadis where the caves are located. The only way to reach these nearly inaccessible caves in the wadi walls is—and, especially at that time, was—from above. But even from above the task was very difficult. There were no roads on the cliffs. To get to the caves, we often had to let ourselves down and up on ropes and rope ladders. Fortunately, we had assistance from the Israeli army. Equipment and food was brought in by hand or by mule.

Our most important find was the remains of two previously unknown Roman military camps, both on the cliffs above the caves. One was north and the other south of the Nahal Hever; both were used by the Romans when they laid siege to Jews hiding in the caves. Both of these Roman camps overlooked the canyon and both were above caves that later proved to be extremely rich in finds. The Roman camps dated to the time of the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 C.E.a). The camp on the south overlooked the cave later known as the Cave of Horrors, because it contained dozens of skeletons—men, 052women and children, apparently Jewish refugees who had been cut off by the Romans from the camp they had built above the caves.

The camp on the north overlooked what later became known as the Cave of Letters. Because for ten years I had been a fisherman, I was assigned the task of securing the rope ladder we dropped down, for example, in the Cave of Horror, from above in order to reach the cave. It took me two days just to tie and aim the ladder; the ladder being over 300 feet long, I knew it had to be secure. In order to reach the Cave of Letters, someone had to descend almost 50 feet by foot along a dangerous path and then climb up the face of a wall from a small ledge, pulling a 60-foot rope ladder after him. In this way we were able to enter one of the two openings of a huge cave containing three different chambers.

The first thing we noticed was obvious: The Bedouin had been there before us. The telltale signs of recent illegal digging were evident throughout the cave—including empty cigarette packs manufactured in Jordan. We retrieved what ancient remains we could, fragments that were apparently regarded as worthless by the Bedouin—mostly broken pottery, some small pieces of cloth and mats and three lids, one made of clay, one of wood and the third made of stone. This third lid had the Hebrew letter shin, which stands for Shaddai (Almighty), one of the Hebrew names of God. Unfortunately, this was not enough for Aharoni to decide whether the cave had been occupied during the two most likely periods—during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.) or the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, the so-called Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–135 C.E.).

Alas, sometimes Aharoni had no mazel (luck).

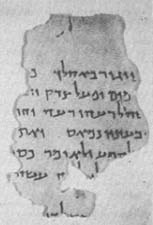

Six years later, several additional documents appeared on the antiquities market, again from an “unknown source.” This time the rumor was that they had come from a wadi even farther south (Nahal Se’elim in Hebrew, Wadi Sieyal in Arabic)—deeper into Israel—even though they were offered for sale in Jordan. Again the Bedouin were ignoring the border, but with greater daring. The response was another Israeli archaeological expedition. It was divided into four teams, each of which explored adjacent wadis, descending into the caves from the cliffs above. Aharoni led one team, and his rival Yigael Yadin led another (the other two teams were led by Pesach Bar-Adon and Nahman Avigad). Aharoni chose the area that included the northern side of the Nahal Se’elim, where the most recent finds were said to have come from and where he found some fragmentary documents. Yadin was left with the area that included the northern side of the Nahal Hever. Nothing much was expected there because the area had already been explored seven years earlier by the Aharoni team of which I had been a member. However, during two campaigns—one in March and April 1960 and a second in March 1961—Yadin’s team made some extraordinary discoveries in this cave: a fragment from the Book of Psalms, a fragment from the Book of Numbers, a cache of documents now known as the Babata archive,b glass, mats, metal vessels, some ancient keys with which they locked their homes when fleeing from the Romans, and, most exciting, the Bar-Kokhba letters (letters from the files of Bar-Kokhba’s military command, including some from and to Bar-Kokhba himself). Because of the Babata archive and 053the Bar-Kokhba letters, the cave has become known as the Cave of Letters.

Some of the documents in the Babata archive bore internal dates to the second century C.E., the time of the Second Jewish Revolt and the years immediately prior to that. The Bar-Kokhba letters were obviously from the same period. A Bar-Kokhba-period coin was minted in the same time period.

Yadin carefully noted the findspot of the small fragment from the Book of Psalms—“near the passage from hall A to hall B.” His surmise was that the fragment had fallen from a possibly intact scroll that the Bedouin had removed from the cave. “We may assume that it actually belonged to a scroll found by the Bedouins and was torn off when they crawled out,” he wrote.1 This scroll has never turned up. One wonders if it is still out there in the hands of some antiquities dealer or, perhaps, an “investor.” That is why I said at the beginning of this article that there may well be other scrolls in the hands of the Bedouin or those who obtained them from the Bedouin.

In Yadin’s second campaign to the Cave of Letters (in 1961), he had found the fragment from the Book of Numbers—in the entranceway of one of the two openings to the cave.2 In addition, Yadin found some papyrus fragments from other documents. Again Yadin surmised that “The Bedouin who ransacked the cave had evidently left by this opening, dropping these fragments on their way out.” “We may assume,” he concluded, “as in the case of the fragment of Psalms found in the first season, that larger pieces of this scroll are now in Jordan.”3 Like the Psalms scroll however, the scroll of the Book of Numbers has not yet appeared—if it was ever retrieved by the Bedouin.

But we can do nothing about that. The more insistent, if no less tantalizing, question is whether there is a lower stratum in the Cave of Letters. In the exposed areas of the cave, it is clear that the Bedouin had already rummaged around and presumably extracted whatever may have been there. If there was anything left, Aharoni and Yadin would have found it.

There are certain areas in the cave, however, where neither Yadin, Aharoni nor the Bedouin could have reached. In the three chambers of the cave are huge piles of boulders that had fallen from the roof of the cave; Yadin correctly assumed that these collapses had occurred, “in the main, before the time of Bar-Kokhba.”4 The roof of the cave in chamber B (which is be of particular interest) is approximately 30 feet above the floor. The pile of boulders that fell from the roof in chamber B is nearly 20 feet high. You can imagine what a pile of stones it is! Even Yadin, in 1962, conceded that “We could not move the enormous blocks of fallen rock”5—even with the use of hydraulic hammers. They simply “examined all the cracks and cavities and also removed the small and medium-sized stones.”6 The investigation was thus limited to what was accessible.

Eight years earlier, Aharoni’s team had tried to move a few of the boulders at the edge of the pile, but we were successful in only a few cases—the boulders were simply too large. Moreover, the entire pile of boulders was covered by bat dung. Every time we moved a boulder, we stirred up a cloud of acrid dust that made it almost impossible to breathe.

But I was young and slim and lithe in those days, and strong in the bargain. I offered to try to shift some of the boulders and wriggle in among the gaps. I climbed up about halfway on the west side of the pile in chamber B7 and shifted a few of the boulders. Then I began to descend snakelike in among the gaps, with my arms thrust forward, shining a powerful flashlight ahead of me.

When I had penetrated down to about the length of my body, I glimpsed by the light of the flashlight, pinned under the boulders, a human skeleton lying on its side with its arms and legs asprawl. The skeleton was clothed in a white robe. Around the waist was a rope belt, knotted in front.

The discovery of this skeleton made a powerful impression on me that remains vivid to this day. Of course I could not see the entire skeleton, only those parts that were visible under the glare of my flashlight through the gaps in the boulders.

I immediately reported the discovery to Aharoni, 054who rushed back into the chamber with me, carrying a few padded cardboard boxes. I again wriggled down among the boulders and, raising my voice, I described to Aharoni what I was able to see: the skeleton, the posture, the clothing. He instructed me to remove whatever I could. I strained, painfully squeezing between the boulders, gasping for breath. Finally I managed to reach the middle part of the skeleton. I pulled away the rope belt and part of the robe. Once I reached them, they were easy to pull out; apparently the underside of the robe and the belt beneath the skeleton had rotted and disintegrated. I was unable to get any of the bones, however.

When I emerged from the maze of boulders covered with centuries-old dust and bat dung, I presented Aharoni with the piece of the robe and the belt. It was a moving moment for me. I remember the thought that flashed through my mind after discussing the find with Aharoni. Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian tells how the Essenes would give an initiate “a girdle and a white garment.” I pictured my “Essene” slowly walking about dressed in the white robe and rope belt I handed to Aharoni. “He will perpetually be a lover of truth… [and will never] endeavor to outshine his subjects, either in his garments or any 055other finery,” wrote Josephus.8

Aharoni placed the robe and belt in one of the cardboard boxes. Today no one knows where they are. My effort to find them in the stores of the Antiquities Authority proved fruitless. It may be that they never reached Jerusalem; I recall that one of the boxes containing finds, which was carried to our base camp at Ein Gedi by the IDF soldiers who were helping us, did not get there and was either lost, stolen or forgotten on the way.

The implications of this robe and rope are of extreme importance. The position of the skeleton under the heavy boulders clearly indicates that this was no ordinary burial; the skeleton lay sprawled out, apparently crushed when the roof of the cave collapsed. All the other datable finds capable of distinguishing between the First and Second Revolts were found on top of the collapse, not from beneath it. In any event, this proves that there is something from an earlier period under the pile of boulders: There is definitely a lower stratum. The Bedouin knew this. They dug some tunnels under the piles of boulders; apparently they had discovered something and were looking for more. As Aharoni noted in his report, “We noticed that the Bedouin had dug several small, narrow tunnels and had crawled between the piles of stones; they were, however, unable to move them. There was no possibility of a proper archaeological excavation.”9

056

What finds lie beneath these huge piles of rocks can only be determined by removing them and then excavating. With the facilities available to us today, this can be done much more easily than 40 years ago. There is no doubt in my mind that it should be done!

I should add that Aharoni was fully aware of the importance of the stratum beneath the pile of boulders. In his published report, he noted that “all of the central chamber and most of the last one—where the bones were found—could not be properly explored and excavated owing to the heavy rock-falls covering the floor… The few days available to the expedition were not enough to thoroughly research this large cave and clear up the problem of dating and period of its occupation. A great deal of research work, including overcoming the technical difficulties involved in removing the piled-up boulders from the cave’s floor, still awaits the expedition over the next few years.”10

As we have noted, Yadin, too, was aware of the problem posed by the rockfalls.11 It is clear that we now have the time and the technical ability to remove these large piles of rocks and carefully excavate underneath them.

But the Cave of Letters is not the only cave that should be reexcavated. The reason relates to the cause of the roof collapse in the Cave of Letters. I consulted a geologist from the Israel Geological Institute who studies ancient earthquakes, Dr. J. Kurtz, who explained to me that, theoretically, there were three possible causes of the roof collapse in the Cave of Letters: (1) fatigue of the stone in the roof—areas with minor cracks finally broke loose—what geologists call progressive fissuring; (2) water cutting the roof area away; and (3) earthquake.

The first two would be local phenomena. The third, earthquake, would affect other caves as well. This is an area of relatively frequent earthquakes. The Jordan Valley, the Dead Sea (the lowest spot on earth) and the Arabah (the valley south of the Dead Sea) are all part of the Great Rift that extends through the Red Sea into Africa. It marks the edge of two tectonic plates that, in geological terms, rather frequently rub up against one another, causing earthquakes.c

According to Dr. Kurtz, 10 to 15 relatively strong earthquakes occurred in this region in the 300-year period from about 250 B.C.E. to 70 C.E., when most scholars date the Dead Sea Scrolls associated with the Wadi Qumran. One of these earthquakes is especially famous. We know precisely when it occurred—in the seventh year of Herod’s reign, according to Josephus.12 This places it in the year 31 B.C.E.

Archaeologists have used this earthquake in 31 B.C.E. to explain the destruction of an early settlement at Qumran and its temporary abandonment. They have also used it to explain the destruction of the Herodian palaces near Jericho, a few miles north of Qumran. It is tempting to attribute the collapse of the roof in the Cave of Letters to this same earthquake, but only renewed excavations can test this hypothesis. Only by examining the material under the huge rock pile would we be able to answer this question with any confidence.

More intriguing still, archaeological reports are replete with references to other caves in this area whose roofs have collapsed. For example, in Pesach Bar-Adon’s report of his 1960 survey of caves in the Judean desert, he states: “We investigated tens of caves… several large and deep ones, their floors covered by large rock-falls.”13 In one cave Bar-Adon found two 057scroll fragments, one in Greek and the other in Hebrew. The Hebrew one, he says, “was found near a later rock-fall.” Bar-Adon then adds: “Perhaps the missing part of the complete scroll is yet pinned under these rocks.”14 I need only add that Bar-Adon also found pottery in these caves dating to the first century B.C.E. and earlier.

In a 1970 return to the same area, Bar-Adon reports that in a “large number of caves, the floors are covered with huge rocks.”15 In short, it appears that the ceiling collapses in the caves were a result of earthquakes, or perhaps one major earthquake, that buried artifacts and perhaps scrolls from the period before the Roman destruction of the Temple (70 C.E.).

Most of the 11 caves in the area of the Wadi Qumran that were found to contain inscriptional material were discovered by Bedouin, not by archaeologists. One of the few exceptions was Cave 3. The most intriguing find from Cave 3 is the famous Copper Scroll, the only scroll from antiquity that is inscribed on metal. Over 7.5 feet long, the Copper Scroll is a list of 64 hiding places of huge amounts of gold and silver. Many scholars believe it is a guide to where the Temple treasure was hidden to prevent its capture by the Romans.d Cave 3 was found by archaeologists instead of Bedouin because the mouth of the cave was blocked by large stones that had fallen from the roof, probably as a result of an earthquake. The Copper Scroll also mentions a second copy of directions to this buried treasure. Does it lie buried in some nearby cave under a pile of rocks that have collapsed from the roof? While some scholars believe the Copper Scroll is a roadmap to real buried treasure, others believe the inventory is entirely fictional—none of the locations has ever been discovered, despite numerous amateur efforts to do so. Perhaps this debate will never be settled. But the one way it could be settled is if one of the treasure spots were found with the treasure still intact. What more likely place than in an inaccessible cave, guarded by a rockfall from an ancient earthquake?

It is evident that the collapsed roof in the Cave of Letters makes a clean division between two occupational strata inside the cave, the first one underneath the fallen boulders, hiding, perhaps, the signs of an earlier Essene occupation. In my opinion, this may also be true of other caves in the Judean Desert whose roofs collapsed, perhaps in the same earthquake.

For all these reasons—practical and visionary—excavation under the boulders of roof collapses in these caves is mandatory. Today we have the equipment and the know-how to accomplish it. All we need is the will and the financial support. And there is no better place to start than the Cave of Letters, where, 40 years ago, I saw a skeleton clothed in a white robe and a rope belt pinned under the stones.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Yohanan Aharoni, who was a friend to everyone and to me.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Professor Avraham Ronen of Haifa University for his advice and help with the presentation of this article. I am also grateful to Dr. Beno Rothenberg (who took part in the expedition) for his help and encouragement, and to Dr. Bilha Nitzan. I also gratefully acknowledge the help of archaeologist Nurit Faig and Tamar Shik.

With so much public attention lately focused on the Dead Sea Scrolls, the question is frequently asked, with increasing insistence: Are there more scrolls—either undiscovered in the caves or in the hands of the Bedouin or of those who acquired them from the Bedouin? This article will suggest that the answer is yes on both counts. My story begins exactly 40 years ago—in 1953—when I, an Israeli kibbutznik imbued with a love of my people’s past, joined an archaeological team led by the late Yohanan Aharoni to explore some caves in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea. In […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

C.E. (Common Era) and B.C.E. (Before the Common Era), used by this author, are the alternate designations corresponding to A.D. and B.C. often used in scholarly literature.

Babata was a Jewish woman from a village on the shore of the Dead Sea who fled to the cave with her family’s legal documents during the Second Jewish Revolt. See Joseph A. Fitzmyer’s review of The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters: Greek Papyri, edited by Naphtali Lewis, in Books in Brief, BAR 16:03.

See Dan Gill’s review of Amos Nur’s video, “Earthquakes in the Holy Land,” Books in Brief, BAR 17:05.

See P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., “The Mysterious Copper Scroll Clues to Hidden Temple Treasure?” Bible Review, August 1992.

Endnotes

Yadin, “Expedition D—The cave of the Letters,” Israel Exploration Journal 12 (1962), pp. 227–229.

Yohanan Aharoni and Beno Rothenberg, In the Footsteps of Kings and Rebels (Ramat-Gan, Israel Massada 1960), pp. 130–132 (in Hebrew). In Aharoni’s report he indicates that it was found in Chamber c. Because of this discrepancy I have tried to consult the original handwritten diary that Aharoni kept of the expedition, but have not yet been able to do so. If Aharoni’s field notes state that the find was in chamber c, I will accept this correction.

Yigael Yadin, Finds from the Bar-Kokhba Period in The Cave of Letters (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963), p 17 (in Hebrew).

“Judean Desert-Caves Archaeology Survey in 1960,” Yediot (Bulietin of Israel Exploration Society) 25 A-B (1961) (in Hebrew).