Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder.

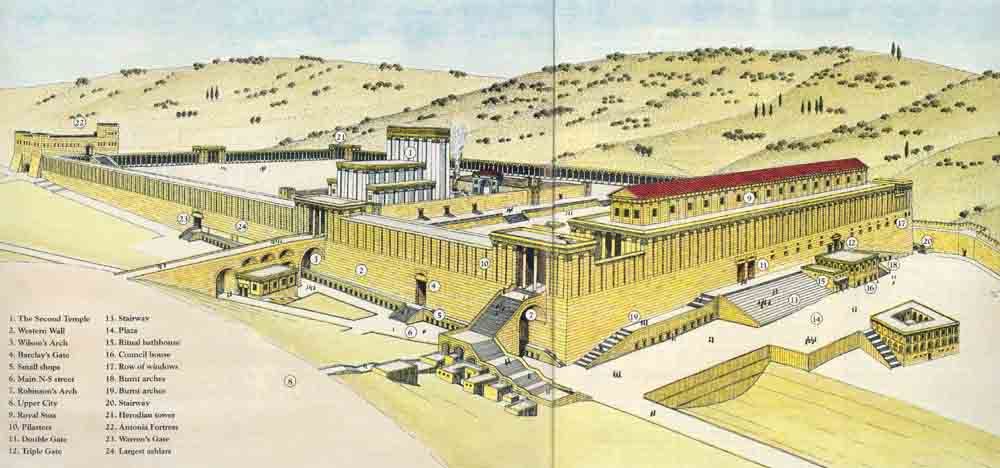

One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size.

Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. Under Ottoman rule (1517–1918), Jewish prayer at the western wall was again permitted, but the Turkish sultans changed the entire character of the Temple Mount by Islamicizing it, so as to make it virtually unrecognizable.

With nothing to go on but literary sources (principally the first-century Jewish historian Josephus) and the bare outline of the retaining wall, it is no wonder that the imaginations of artists over the centuries reigned supreme as they sought to reconstruct the Temple Mount and its immediate environs.

A realistic reconstruction of the area around the Temple Mount became possible only when systematic excavation of the area south and west of it began in 1968, soon after the 1967 Six-Day War. Directed by Professor Benjamin Mazar, on behalf of the Israel Exploration Society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the excavation continued without a break until 1978.

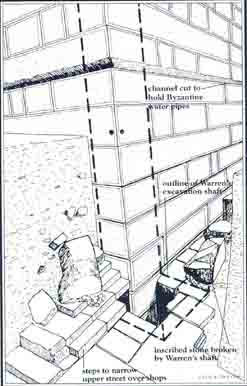

Also of considerable assistance in reconstructing this area are the records of the British explorer Sir Charles Warren, who investigated the Temple Mount environs during the 1860s on behalf of the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund. Warren and his companions dug numerous shafts down to bedrock, as well as horizontal underground tunnels off the shafts to trace long-buried walls and other structures. During the Mazar excavations, we rediscovered some of Warren’s tunnels, which amply demonstrated the daring and courage his digging methods required.

As Professor Mazar’s dig progressed, each wall and stone was surveyed, each architectural element examined. Gradually a complete plan of the multi-period site—from the eighth century B.C. in the Iron Age to the Turkish period—emerged. To reconstruct what the area was like in the time of Herod the Great, the Herodian elements were separated from the other periods. Then we re-examined the ancient sources and searched for parallels in other monumental Hellenistic buildings in an effort to arrive at an accurate reconstruction. A series of architects assisted the archaeologists, of whom Leen Ritmeyer, one of the authors of this article, was the latest.b

Of the Temple itself, we shall not speak.c The Moslem authorities, under whose jurisdiction the Temple Mount lies, do not permit archaeological investigation of the platform. Suffice it to quote Josephus’s observation, “To approaching strangers [the Temple] appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not overlaid with gold was of purest white” (L., The Jewish War 5.5.6).d

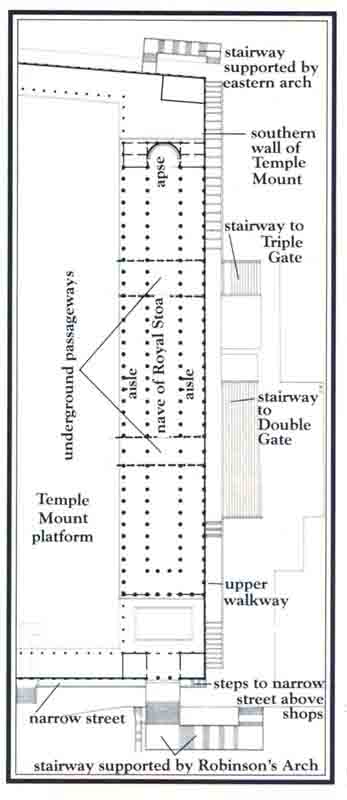

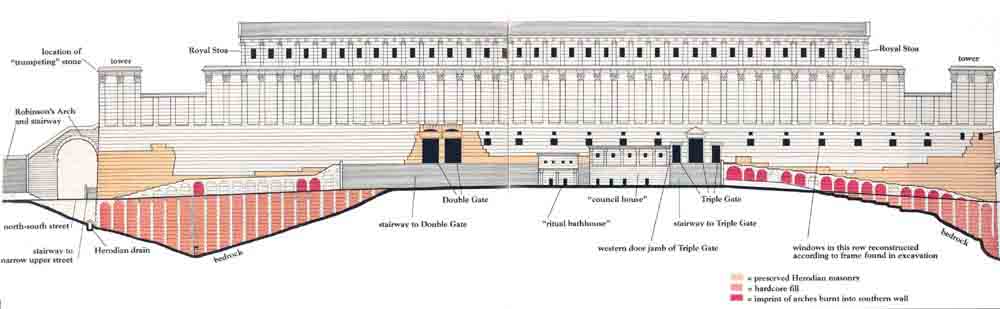

Our reconstruction concentrates on the wall of the Temple Mount, the means of access to the Temple Mount, the gates in the walls and the adjoining streets and buildings. In short, we will make a circuit around the Temple Mount and trace the remains that tell the tale of Herod’s greatness.

Let us begin at the western wall (2).e. It was this fragment of masonry that became the focus for the longing of dispersed Jews throughout the centuries. Then it was known as the Wailing Wall; now it is called the Western Wall or simply ha-Kotel, the Wall. Today it is again a center of worship, and also a site of national celebration. Contrary to common understanding, this wall is not a remnant of the Solomonic Temple Mount.

In order to build his Temple to the Israelite God Yahweh, Solomon needed to construct a level platform on the highest hill of Jerusalem. To accomplish this, Solomon built a retaining wall to support the earthen fill of the platform, the Temple Mount. Herod doubled the area of this platform by building a new wall on three sides—west, south and north—and by extending the fourth wall (the eastern wall) north and south to meet the new southern and northern walls. Today’s western wall is a section of the massive retaining wall Herod built to support the Temple Mount.

In enlarging the Temple Mount, Herod not only doubled the original area of the Temple podium, he also wrought a complete change in the topography of the area. The Tyropoeon Valley, which bordered the Temple Mount on the west, was filled in, as was a small valley to the north of the Old Temple Mount. In the south, the upper slope of the Kidron Valley was filled in, leaving only the line of the eastern wall unchanged.

Josephus described Herod’s retaining wall as “the most prodigious work that was ever heard of by man” (W., Antiquities of the Jews 15.11.3).

An idea of the size of Herod’s Temple Mount can be conveyed by stating that it would take approximately five football fields to fill its area from north to south and three football fields from west to east. Its exact dimensions are shown in the drawing, below; note that it is not exactly rectangular.

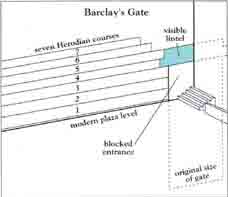

At the present time, only seven courses of Herodian ashlars are visible above the prayer plaza in front of the western wall. Below the plaza level are 19 additional courses of Herodian ashlars. This means that bedrock lies a staggering 68 feet below the plaza. (The shafts dug by Warren adjacent to the wall show us how many courses lie below the surface. These shafts can still be seen north of the prayer area. They are well lit; coins thrown by tourists reflect from the bottom.)

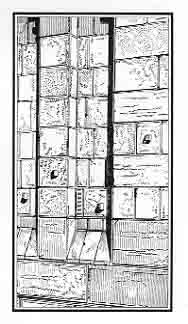

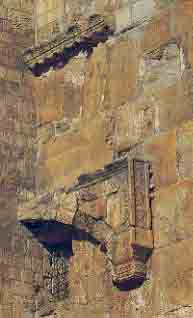

It is not difficult to distinguish Herodian ashlars from those of later periods above them. Herodian masonry has a fine finish, a flat, slightly raised center boss and typical flat margins around the edges. The stones were cut with such precision that no mortar was needed to fit them together perfectly. Some of these ashlars are as much as 35 feet long and weigh up to 70 tons.

North of the open prayer area, under overhead construction, is Wilson’s Arch (3), named after Charles Wilson, the British engineer who first discovered it in the mid-19th century. As it exists today it is probably not Herodian, but a later restoration, the first of a series of arches built to support a bridge that spanned the Tyropoeon Valley, linking the Temple Mount with the Upper City to the west. In Herodian times, an aqueduct also ran over this causeway, bringing water from “Solomon’s Pools” (not really Solomonic) near Bethlehem to the huge cisterns that lay beneath the Temple platform.

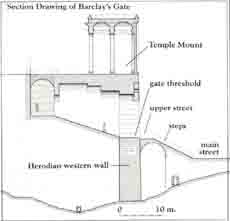

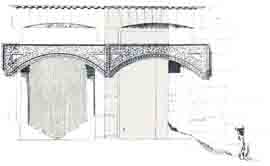

Moving south from Wilson’s Arch, we come to a gate in the western wall. Known today as Barclay’s Gate (4), after its discoverer—J. T. Barclay, a British architect who worked in Jerusalem a short time before Wilson and Warren—it has been almost completely preserved. The only section now visible, however, is the northern half of its massive lintel (almost 27 feet long and 7 feet high) and the top three stones of its northern doorpost. These form part of the western wall at the southern end of the area today reserved for women (by Orthodox Jewish law, men and women worship separately). The remainder of the gate is obscured by the earthen ramp leading up to the Moor’s Gate, which is the present-day access to the Temple Mount from this area.

We know the level of the original threshold of Barclay’s Gate from Warren’s records. Our excavation revealed the level of the Herodian street in front of the gate. There is a difference of about 13 feet between the level of the street and the level of the threshold of Barclay’s Gate. This difference rather baffled us until another bit of seemingly trivial information, recorded by the indefatigable Warren, provided the missing piece of the puzzle.

Warren tells us that while digging in the area, he saw the remains of a vaulted chamber protruding from below the threshold of Barclay’s Gate. Warren assumed that this must have been part of a lower viaduct that crossed the Tyropoeon Valley, but on a much smaller scale than the bridge supported by Wilson’s Arch. Additional clues from our excavation have led us to conclude that this vault supported a staircase that led up to Barclay’s Gate from the main Herodian street. At the southern corner of the western wall, we found a flight of six steps, 10 feet wide, leading north. Somewhat farther north (about 46 feet south of Barclay’s Gate), we found two walls built perpendicular to the western wall. A row of many similar walls, perpendicular to the southern wall, had been found earlier. These we assume to be the remains of commercial premises frequented by visitors to the Temple. If that is true, the two walls perpendicular to the western wall probably also formed part of a similar arrangement of small cells on this side (5). The flight of steps at the southern end of the western wall must therefore have led up to a narrow street that ran over the roofs of these shops. Finally, the vault observed by Warren must have carried a staircase that connected the lower street (the main street [6]) with this narrow upper street, giving access to Barclay’s Gate. Thus, the 13-foot difference between the level of the main Herodian street and the threshold of Barclay’s Gate was now explained.

The fact that the main Herodian street stopped short of the western wall by 10 feet strongly supports this reconstruction. The small shops adjacent to the western and southern walls formed part of the Upper and Lower Markets of the city, as described by Josephus. The main Herodian street ran from Damascus Gate in the north to the Siloam Pool in the south, through the Tyropoeon Valley; the shops adjacent to the western wall of the Temple Mount fronted on this street.

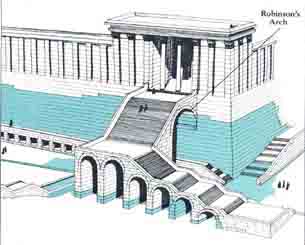

The next element we will examine is Robinson’s Arch (7), which protrudes from the western wall south of Barclay’s Gate. In fact, Robinson’s Arch is barely the spring of the arch, in contrast to Wilson’s Arch, which is complete. Robinson’s Arch is named after the American orientalist Edward Robinson, who in his travels in Palestine in the second third of the 19th century correctly identified dozens and dozens of Biblical sites. It was he who first identified this arch that bears his name. From its discovery until the time of our excavation, it was generally assumed that Robinson’s Arch was the first of a series of arches that supported another causeway spanning the Tyropoeon Valley in the same way as the bridge that began at Wilson’s Arch. At the beginning of our excavations, a hypothetical reconstruction based on this theory was indeed drawn up. However, when we found no other piers in addition to those that had supported Robinson’s Arch, and that had already been discovered by Warren, we turned in perplexity to Josephus. He described the gate to the Temple Mount that must have existed above Robinson’s Arch as follows:

“The last gate [in the western wall] led to the other city where the road descended down into the valley by means of a great number of steps and thence up again by the ascent” (W., Antiquities of the Jews 15.11.5).

According to Josephus, this gate led from the Temple Mount, not over the Tyropoeon Valley via a bridge to the Upper City (8) on the west, but rather to “the valley” below by means of “a great number of steps.” Access to the “other city,” the Upper City on the west, was obviously via steps leading up from the valley.

Excavations proved the accuracy of Josephus’s description. The archaeologists discovered a series of piers of arches of graduated height, ascending from south to north. The arches were equidistant. At the top is a turn eastward over Robinson’s Arch. On this basis a monumental stairway has been reconstructed, leading from the Royal Stoa (9) on the Temple Mount down to the street in the Tyropoeon Valley. From there one could ascend to the Upper City or south to the Lower City.

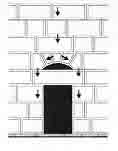

Beneath Robinson’s Arch, weights, coins, stone vessels and other evidence of commercial activity were found in four small cells. Above the lintel of the entrance to each of these shops was a relieving arch, designed to distribute the downward pressure of the superstructure.f

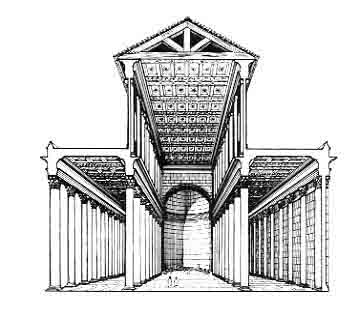

The stairway that ascended over Robinson’s Arch provided an impressive entrance to the Royal Stoa, which Herod built on the southern end of the Temple Mount. Josephus describes this royal portico in some detail (Jewish Antiquities 15.11.5). It was built in the shape of a basilica with four rows of 40 columns each. Each of the huge columns in this veritable forest of columns was 50 feet high. The thickness of each was such, Josephus tells us, “that it would take three men with outstretched arms touching one another to envelop it” (L., Jewish Antiquities 15.11.5). Fragments of columns found in the excavation validate Josephus’s description. Most of these fragments, however, had been reused in later Byzantine and Islamic buildings.

It was probably from this Royal Stoa that Jesus

“drove out all who sold and bought in the Temple, and he overturned the tables of the moneychangers and the seats of those who sold doves. He said to them, ‘It is written, “My house shall be called the house of prayer”; but you make it a den of thieves’” (Matthew 21:12–13; also compare Mark 11:15–17; Luke 19:45–46).

Lying on the main north-south street adjacent to the western wall, the excavators found massive amounts of rubble, testifying to the extensive destruction of the complex inflicted by the Roman general Titus in 70 A.D. Among the various architectural remains found in the rubble were steps from the original monumental stairway, archstones, columns, capitals, friezes and pilasters.

These pilasters are of special interest because they confirm the architectural style of the wall of the Temple Mount: flat in the lower part, with pilasters, or engaged pillars (10), in the upper part. These rectangular engaged pillars were set into the wall and topped with capitals.

A complete Herodian wall in this same style has survived intact in the structure surrounding the Tomb of the Patriarchs (Machpelah) in Hebron.g

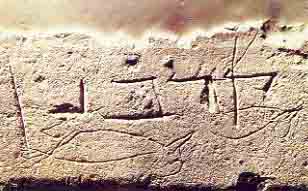

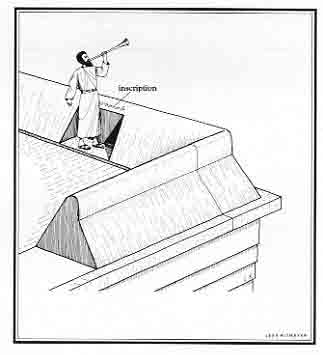

On the Herodian street near the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, the excavators found a large stone block with a Hebrew inscription carved on it. Unfortunately, the end of the inscription is not on this fragment. The piece containing the final letters of the inscription had broken off, leaving the inscription open to various interpretations. The surviving part of the inscription can be vocalized l’bet hatqia l’hak … , which may be translated “to the place of trumpeting l’hak– … ”

Various possibilities have been suggested to complete l’hak—l’ha-kohn (for the priest), l’hekal (toward the temple); or l’hakriz (to herald [the Sabbath]).h Whatever the correct ending, it is clear that this inscription was a direction to the place where the priest stood to blow the trumpet to announce the commencement of the Sabbath and feast-days as mentioned in Josephus (The Jewish War 4.9.12). Most scholars have assumed that the direction was for the priest himself, to mark the place where he was to stand. Another possibility, however, is suggested by traces of fine white plaster found on parts of the stone. This indicates that the inscription itself may not have been visible after the stone was in place. The entire inscription may simply have been a mark inscribed in the quarry to indicate to the builders where to place the stone. The fact that the carving is not particularly beautifully executed would support this theory.

One thing is clear, however: the stone could have come only from the top of the southwest corner of the Temple Mount. Found lying on the Herodian street, underneath other stones that had fallen from the tower above, it could not have been transported here from any other place. The tower at the southwest corner of the Temple Mount stood at a height of approximately 50 feet above the level of the Temple court. The Romans would never have moved the stone from another part of the Temple precincts and then hoisted it up to the tower and dropped it on the pavement before destroying the tower. The fact that the inscription is incomplete gave rise to theories that the original location of the trumpeting stone was elsewhere.i Here is one instance where Warren’s excavation method—the digging of shafts and tunnels—detracted from, instead of supplemented, our understanding of the remains. Warren almost certainly cut off the remainder of the inscription on this stone while digging his shaft in darkness at the southwest corner of the Temple Mount. Happily, he was unaware of the controversy that would rage when the stone was uncovered some hundred years later.

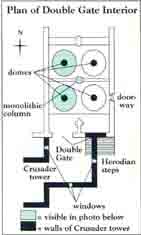

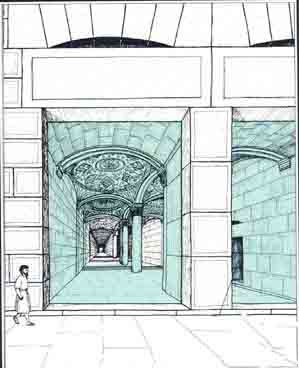

Let us turn now to the southern wall of the Temple Mount (drawing, above). Even before our excavations began, the locations of its two main features, the Huldah Gates (called after the prophetess of that name—see 2 Kings 22:14; 2 Chronicles 34:22), were known. The remains of these gates are visible in the wall we see today. They are now referred to as the Double Gate (11) and the Triple Gate (12). Few people are aware, however, that the Double Gate has been preserved in its entirety inside the Temple Mount. Its original lintel and relieving arch are still intact. On the outside, the western half and most of the eastern half of the Double Gate are concealed by a Crusader structure built against the southern wall of the Temple Mount in order to protect the Double Gate during the Crusader period. At that time, the southern wall of the Temple Mount served as the city wall, and the center of government itself was located on the Temple platform. The security of the Double Gate required the erection of a massive tower outside it to provide a zigzag entrance. Standing perpendicular to the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the wall that obscures most of the Double Gate on the outside was part of this Crusader tower.

Over the remaining part of the Double Gate still visible on the outside is a decorative applied arch that dates from the Moslem Omayyad period. Originally, however, there was no decoration, or even molding, on the outside.

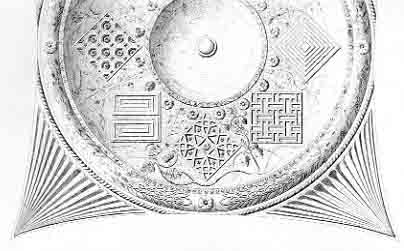

Inside the Double Gate, which gave access to the Temple court, two pairs of domes still delight the eye with their stone-carved decoration. Using floral and geometric motifs, the unique decoration is a fine example of how Herodian craftsmen adapted Roman decorative styles while still conforming to Jewish law, which forbade the representation of human or animal figures.

Some earlier reconstructions of the outside of this gate included additional decoration, such as a pediment (a triangular, roof-shaped decoration above the lintel of a doorway) or a frieze. However, by counting each of the Herodian courses and drawing up an accurate elevation of the whole southern wall, we were able to determine that the top of the relieving arch above the lintel of the Double Gate was level with the internal court. So there would have been no room for any additional decoration. Today’s courtyard level—2,420 feet above sea level—is the same as the Herodian court level. I (Leen) was able to confirm this in 1977 during repairs to the floor of the El Aqsa mosque, which lies above the Double Gate. At that time, just below the floor, I saw a circular keystone—the top of the dome of the Double Gate.

In Herodian times, access to the Double Gate from outside was chiefly by means of a broad stairway (13), founded on the natural bedrock of the Temple Mount slope. The stairway’s eastern end extends 105 feet east of the centerpost of the Double Gate. In our reconstruction, we have assumed that the stairway was built on the central axis of the Double Gate so that it therefore also extended 105 feet west of the Double Gate’s centerpost. Accordingly, the total width of the stairway is shown to be 210 feet—an impressive entranceway indeed! The 30 steps, which were laid alternately as steps and landings, were conducive to a slow, reverent ascent. This monumental stairway also provides a moving pictorial setting for an incident described in the Talmud,j in which we are told, “Rabban Gamaliel and the elders were standing at the top of the stairs at the Temple Mount” (Tosefta, Sanhedrin 2:2).

From the viewpoint of design and town-planning, it is evident that a wide plaza (14) must have existed south (in front) of the steps leading to the Double Gate. Paving stones in a small area, approximately 16 feet square, withstood the ravages of time to confirm the existence of this plaza. The rest of the paving slabs were taken by later builders who needed construction material. Approximately 100 feet south of the steps, the archaeologists found evidence of what was probably the foundation of the plaza. This suggests that the dimensions of the plaza were what we should expect them to have been. Its size was apparently comparable to similar plazas in the ancient world, at such places as Athens, Priene and Assos.

Between the Double Gate and the Triple Gate, our reconstruction drawing shows two buildings. The one to the west (15) was a bathhouse for ritual purification; many mikva‘ot (ritual baths) cut into the bedrock have been found there. The building to the east (16) was probably a council house, indicated by the many bedrock-cut Herodian chambers (rooms) found near the Triple Gate. This building may have been the first of the three courts of law located in the Temple precincts, as mentioned in the Mishnah:k “One [court] used to sit at the gate of the Temple Mount, one used to sit at the gate of the Temple Court and one used to sit in the Chamber of Hewn Stone” (Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 11:2).

If the Double Gate was for pilgrims to enter and exit, the Triple Gate was used by members of the priestly order to reach the storerooms where the wine, oil, flour and other items needed in connection with the Temple service were kept. From there, of course, they could also reach the Temple platform.

On either side of the Triple Gate, we have reconstructed a row of windows (17). Their existence has been supposed on the basis of a finding in the immediate area, a window frame with grooves for metal bars. Some provision for light and air was needed for the underground storeroom. This fact, combined with the window frame, is the basis for the windows we have reconstructed.

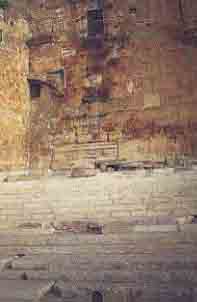

Excavations found the area near the southeast corner of the Temple Mount to be devoid of architectural remains, as it had served as a quarry for construction during later periods. Our workers cleared away the accumulated rubble from the wall, thereby exposing the original stones. One day, while surveying the bedrock foundations of Herodian rooms that adjoined the southern wall on the outside, east of the Triple Gate, we noticed something unusual. The imprint of arches burnt into the stones was clearly discernible on the Herodian wall. These arches descended in height toward the southeast corner of the Temple Mount. They were all that remained of small cells, probably shops (18), that lay below the stepped street that skirted the Temple Mount wall.

The tragedy of the Roman destruction comes vividly to life as we imagine the only possible scenario that would have left such an indelible imprint on the southern wall. The limestone ashlars used in the Herodian construction can be reduced to powder when exposed to very high temperatures. The Roman soldiers must have put brushwood inside the chambers and the blaze created when this was set alight would have caused the arches to collapse. The street that was carried by these arches also collapsed. Before the arches collapsed, the fire burnt into the back wall of the chambers, leaving the imprint of the arches as evocative testimony to the dreadful inferno. Josephus writes that, after having burnt the Temple, “The Romans, thinking it useless, now that the Temple was on fire, to spare the surrounding buildings, set them all alight, both the remnants of the porticoes and the gates … ” (L., The Jewish War 6.5.2).

In the western part of the southern wall (19), three similar arches were subsequently discovered burnt onto the wall. Two flights of three steps each, with a landing in between, still exist near the southwest corner. The continuation of this pattern of steps and landings along the southern wall from west to east reaches exactly to the top of the first visible burnt arch. From the third visible arch (which is, at its center, 282 feet east of the southwest corner), a sharp flight of steps has to be inserted to reach the level of the top of the stairway leading to the Double Gate.

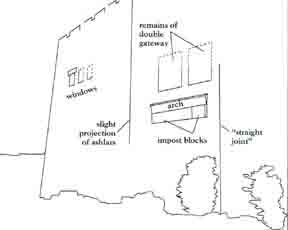

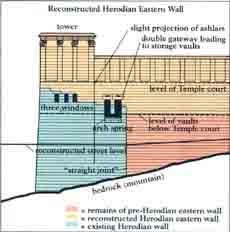

Now let us proceed to the eastern wall of the Temple Mount, which today has a Moslem cemetery in front of it. Some 130 feet of this ancient wall was exposed by a bulldozer prior to 1967. Despite the lack of scientific excavation on this side of the Temple Mount, many clues to its former appearance are preserved in the jigsaw of stones that make up the wall. Three Herodian windows, one with its lintel still in place, can be discerned in the Herodian tower just north of the southeast corner. This tower loomed high above the Kidron Valley and is sometimes identified as the “pinnacle of the Temple” referred to in Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness (Matthew 4:5; Luke 4:9).l Some 100 feet north of the corner (directly opposite Robinson’s Arch on the western wall) the beginning of an arch-spring can be seen. The springing arch was set on impost-blocks with large bosses (raised center portions) still visible. This arch apparently supported a stairway (20) that descended to the road that ran along the eastern wall. (In this, it paralleled the stairway over Robinson’s Arch on the other side of the Temple Mount.) At the top of the stairway, a double doorway, also partially preserved, led into storage vaults, erroneously called Solomon’s Stables. Although above street level, these vaults lay below the level of the Temple court. Perhaps wine, flour and incense for Temple rituals were stored here. The vaults were probably connected with the Triple Gate passageways, which led up to the Temple court and which were used by the priests.

At a point in the eastern wall, 106 feet north of the southeast corner, is a seam in the masonry—the famous “straight joint.” Obviously the part of the wall south of this seam was added to the earlier wall. The masonry on the two sides of this seam are quite distinct from one another. The southern extension is clearly Herodian and is remarkably well-preserved. The date of the wall north of the “straight joint” is still the subject of heated controversy.m

The location of the gate to the Temple court in the eastern wall is, as yet, undetermined. The only visible entranceway, the Golden Gate, dates from the Early Islamic period (seventh century). The arch of another gaten lies directly beneath the blocked entranceway of the Golden Gate, but the location of this lower gate precludes its being Herodian. This lower gate is flush with the Golden Gate that is visible today. The Golden Gate protrudes from the line of the wall, so the lower gate does also. But none of the other gates of the Herodian enclosure wall around the Temple Mount protruded from the wall as this one does. In fact, gates set flush in the wall are also the rule in the other Herodian sacred precincts, such as the ones at Damascus and Hebron.

At the northeast corner of the Temple Mount, the Herodian tower (21) still stands to a considerable height. One of the original shooting-holes of the tower is still visible today.

At the northwest corner of the Temple Mount stood the Antonia Fortress (22), built by Herod on the site of an earlier fortress and named after Mark Antony, the Roman commander. Josephus relates that the Antonia Fortress was built as a “guard to the Temple.” Manned by a Roman legion, the fortress had a tower on each of its four corners. The southeast tower was 70 cubits high (approximately 112 feet) “and so commanded a view of the whole area of the Temple” (L., The Jewish War 5.5.8). Josephus tells us that the Antonia Fortress was erected on a rock 50 cubits (approximately 80 feet) high and was situated on a great precipice. Archaeologists believe it was located on the rock scarp where the Omariya School now stands. Although not a trace of the fortress itself has been found, one of the large buttresses of the fortress was revealed in the tunneling conducted along the western wall by the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

This project has also brought to light the western wall’s remaining Herodian gate (23), previously discovered by Warren while tunneling under rigorous conditions. Since its original discovery by him, it has been known as Warren’s Gate. Immediately to the south of this gate, the largest stones (24) in the Temple Mount have been found. They are almost 11 ½ feet high. The largest of four especially impressive stones is 47 ½ feet long. It weighs approximately 400 tons.

We have now made the full circuit round the Temple Mount wall. In our own way, we have followed the injunction of Psalm 48:

“Walk around Zion, circle it;

count its towers,

take note of its ramparts;

go through its citadels,

that you may recount it to a future age.”

(We wish especially to thank Professor Benjamin Mazar of the Hebrew University, who has always encouraged us and has allowed us to publish material from the Temple Mount excavations in this article.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

According to the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, Herod began to build the Temple in the 18th year of this reign (19 B.C.); the Temple itself took only 18 months to build and the cloisters were completed within eight years. However, a reference in the Gospel of John 2:20 (“It has taken 46 years to build this Temple”) suggests that the project continued for a much longer time.

The original architect on this excavation was Munya Dunayevsky, who had collaborated closely with Professor Mazar on many earlier excavations for over 30 years until his untimely death in 1969. Dunayevsky made a major contribution to the initial stratigraphical analysis of the site, and his drawing of the southwest corner of the Temple Mount shows the preliminary understanding of the superstructure of the western wall.

Following Dunayevsky’s death, the Irish architect Brian Lalor introduced the technique of three-dimensional reconstruction drawing to the dig. The basic concept of the reconstruction of the area around the Temple Mount is his. Lalor’s catalogue of architectural elements provided an overview of the composite style employed in Herodian architecture. It was he who first suggested that Robinson’s Arch supported, not a bridge, but a monumental stairway.

Following in Lalor’s footsteps came David Sheehan, another Irish architect, and Leen Ritmeyer, from Holland. David Sheehan worked out some of the problems of the street adjacent to the western wall, adding the shops for which evidence had been found and the flight of steps that led up over them alongside the western wall. Details of Leen Ritmeyer’s contribution are contained in this article.

For a detailed description of Herod’s Temple, according to Josephus and Mishnah Middot (a rabbinic source), see Joseph Patrich, “Reconstructing the Magnificent Temple Herod Built,” Bible Review, October 1988. (Drawings in this article by Leen Ritmeyer.)

The quotations from Josephus’s works come from the Loeb Classical Library edition (abbreviated “L.,” comprising The Jewish War, tr. H. St. J. Thackeray, and Jewish Antiquities, tr. Ralph Marcus and Allen Wikgren) or from The Works of Josephus, tr. William Whiston (abbreviated “W.”).

A relieving, or discharging, arch is an arch built into the wall above the lintel of a doorway. Without it, the pressure of the wall construction would break the lintel stone. The relieving arch diverts the pressure that comes from above through the arch stones to the side parts of the opening, as illustrated in the drawing. Arrows show diversion of pressure from above.

See Nancy Miller, “Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years,” BAR 11:03; and Dan Bahat, “Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?” BAR 12:03.

See Aaron Demsky, “When the Priests Trumpeted the Onset of the Sabbath,” BAR 12:06.

See Asher S. Kaufman, “Where Was the Trumpeting Inscription Located,” Queries & Comments, BAR 13:03.

The Talmud (tahl-MOOD) is a collection of Jewish laws and teachings comprising the Mishnah and the Gemara (a commentary on the Mishnah). There are two Talmuds. The Palestinian (or Jerusalem) Talmud was completed in the mid-fifth century A.D.; the Babylonian Talmud, completed in the mid-sixth century A.D., became authoritative.

The Mishnah is the collection of Jewish oral laws compiled and written down by Rabbi Judah the Prince in about 200 A.D.

The devil took Jesus up to the “pinnacle of the Temple” and told him to throw himself down in order to prove he was the Son of God. Jesus replied, “It is written, ‘You should not tempt the Lord your God.’”

For one view and a review of the arguments, see Ernest-Marie Laperrousaz, “King Solomon’s Wall Still Supports the Temple Mount,” BAR 13:03.

See James Fleming, “The Undiscovered Gate Beneath Jerusalem’s Golden Gate,” BAR 09:01.