Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, many scholars considered the Fourth Gospel—the Gospel According to John—to be a mid-to-late-second-century composition inspired by Greek philosophy.

Today, 45 years later, a growing scholarly consensus finds John to be a first-century composition. More surprising still, it is perhaps the most Jewish of the Gospels. Elements that were once thought to be reflections of Greek philosophy were all there at the time in contemporaneous Palestine.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have been a, if not the, major force in this paradigmatic shift in the winds of Johannine scholarship.

The earlier view—that John was late and Greek—was first espoused over 125 years ago as the acids of biblical criticism cut through the cherished assumption that the Gospel of John was written by the apostle John, the son of Zebedee. F.C. Bauer, the founder of the Tübingen School, the first institution to develop and follow the historical critical method, claimed in 1847 that the Gospel of John was written around 170 C.E.a1 Professor A. Loisy, the distinguished 19th-century biblical expert in Paris, concluded that John was written sometime after 150 C.E. This dating was slowly but widely accepted by many leading experts. John was thus regarded not only as the latest of the canonical Gospels, but, because of this late date, unreliable historically. Clearly, as a second-century composition, it could not have been written by an eyewitness to Jesus’ life and teachings, let alone by an apostle. John’s Logos concept-that Jesus was the Word (John 1:1–18)—aligned him with the pre-Socratics, such as Heraclitus, or with the Stoics. He was a genius all right, but one who worked alone in his study, influenced by Greek philosophy. His Gospel was obviously the most Greek of the Gospels.

This view persisted even into the 1950s. Now almost all of this scholarship must be discarded.

Today many scholars conclude that the Gospel of John may contain some of the oldest sections of the Gospels, and that it is conceivable that some of these oldest sections may be related in some way to an apostle, perhaps John himself.2 Moreover, the Gospel of John is now widely and wisely judged to be the most Jewish of the Gospels.

Even before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, another manuscript discovery established that John’s Gospel could not be later than about 125 C.E. Papyrus 52, preserved in the John Rylands Library of the University of Manchester, was acquired by Bernard P. Grenfell in 1920. It consists of fragments from a codex (that is, a bound book) containing John 18:31–33 and 37–38. They most probably come from a book of the Gospel of John in final form; it did not come from a source utilized by the author of John. According to expert paleographers who have studied Papyrus 52, it dates to no later than 125 C.E. and may even be as early as 100 C.E.3 The Gospel of John, therefore, was already in final form by the end of the first century C.E.

Today, no scholar would date John after the first decade of the second century C.E.; most will agree that it dates from around 100 C.E. or perhaps a decade earlier. Hence, John is now perceived to be a late first-century composition in its present edited form.

With the shifting date of its composition also came a revised assessment of John’s historical reliability. In pan this has been the result of archaeological excavations. For example, in John 5:2 the author describes a monumental pool with “five porticoes” inside the Sheep Gate of Jerusalem where the sick came to be healed; the pool, we are told, is called Bethsaida. No other ancient writer—no author or editor of the Old Testament, the Pseudepigrapha, not even Josephus—mentions such a significant pool in Jerusalem. Moreover, no known ancient building was a pentagon, which was apparently what John was describing with five porticoes. It seemed that the author of John could not have been a Jew who knew Jerusalem.

Archaeologists, however, decided to dig precisely where the author of John claimed a pool was set aside for healing. Their excavations revealed an ancient pool with porticoes (open areas with large columns) and with shrines dedicated to the Greek god of healing, Asclepius. The pool had porticoes: one to the north, one to the east, one to the south, one to the west and one transecting the roughly rectangular structure (making it actually two pools).4 The building thus had five porticoes and was dedicated to healing. The author of John knew more about Jerusalem than we thought.

The famous Copper Scroll found in Qumran Cave 3 adds another dimension to this fascinating research. As readers of BR were recently informed,b the Copper Scroll describes 64 places where the Temple treasure was hidden to prevent its falling into the hands of the Romans when, in 70 C.E., they besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple. The Copper Scroll describes in frustrating detail some of the topography in and around Jerusalem. In one column it apparently refers to the Pool of Bethsaida mentioned by the author of John, although this reading is far from certain.5

But the major impact of the Dead Sea Scrolls on our understanding of the Gospel of John relates to John’s conceptual world and theology, especially the dualism that pervades it.

For example, in John 12:35 Jesus says:

The light is with you for a little longer. Walk while you have the light, lest the darkness overwritten take you; he who walks in the darkness does not know where he goes. [Italics highlight terms also found in the Dead Sea Scroll known as the Rule of the Community].

Here we clearly see the dualism of light and darkness. In the very next verse Jesus exhorts his listeners to become Sons of Light: “Believe in the light, that you may become Sons of Light.”

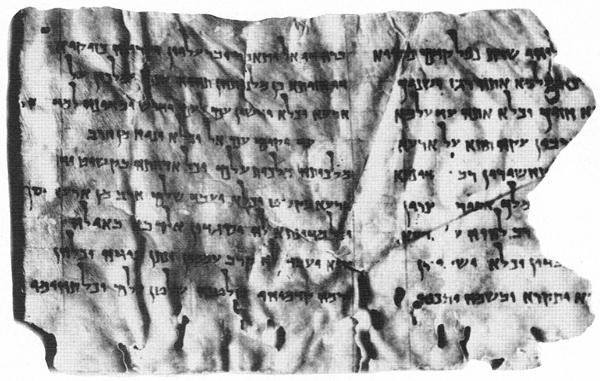

This same dualism is found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially in the text known as the Rule of the Community (1QS). This manuscript even refers to the Sons of Light:

“The Master [maskil] shall instruct and teach all the Sons of Light …” (Rule of the Community 1QS 3.13).

Jesus preaches that the people can be “Sons of Light.” In the Rule of the Community, the Master teaches how to behave as “Sons of Light.” As in John, the Rule of the Community contrasts the light and the darkness in this striking eschatological passage:

He has created the human for the dominion of the world, designing for him two spirits in which to walk until the appointed time for his visitation, namely, the spirits of truth and deceit. In a spring of light emanate the nature of truth and from a well of darkness emerge the nature of deceit. In the hand of the Prince of Lights (is) the dominion of all the Sons of Righteousness, in the ways of light they walk. But in the hand of the Angel of Darkness (is) the dominion of the Sons of Deceit, and in the ways of darkness they walk” (Rule of the Community, 1QS 3.17–21).

The dualism in John cannot be traced back to Platonic idealism, as once thought. Nor is the dualism in John paralleled in Greek, Roman or Egyptian thought. Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, it was assumed it could not be found in Judaism, either. What scholars could not find within Judaism, however has now turned up clearly and boldly in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In the passages from the Rule of the Community already quoted we find a cosmic dualism characterized by two powerful forces (both are angels). This dualism is expressed in terms of a light-darkness paradigm, with humans the center of the struggle and divided into two lots: the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness.

The quoted passage from the Rule of the Community was so important in the Qumran community that it was among the texts that initiates were required to memorize. (The initiates spent two years learning the community’s rules, were examined in them and came from a culture in which memorization of large portions of scripture was characteristic of the learned male.)

The same contrast we find in the Rule of the Community between light and darkness, corresponding to good and evil, is also found, for example, in the text known as the War Scroll (1QM) which depicts a final eschatological battle between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness.

In one of the most famous passages in John’s Gospel, we find not only this same dualism, but also the proclamation (kerygma) that Jesus is God’s only Son:

For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that all who believe in him should not perish but have eternal life. For God sent the son into the world, not to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him. He who believes in him is not condemned; he who does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than the light, because their deeds were evil. For all who do evil hate the light, and do not come to the light, lest his deeds should be exposed. But he who does the truth comes to the light, that it may be clearly seen that his deeds have been accomplished through God6 (John 3:16–21) [The italicized terms, most likely inherited from the Qumran sect.]

Of course no Qumranite would agree that Jesus was the Son of God, but much of the symbolism is the same. The spirit of the Fourth Gospel is definitely Christian and peculiarly Johannine, but the mentality was inherited. The source, or at least one of the major sources, is clearly Qumran terminology and symbolism.

The passage from John refers not only to “the Son,” but also to ‘the Son of God.” Not long ago, we would have said that these terms were not to be found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. But fragmentary scrolls recently made available now reveal a different picture. Of course the Qumran community knew from Psalm 2 about the concept of being God’s son, but this was not a messianic use of the concept (Psalm 2 says: “[The Lord] said to me: ‘You are my son; today I have begotten you. Ask of me and I will make the nations your heritage …’”).

In the Dead Sea Scrolls we now find a messianic use of the concept. A fragment called 4Q246 refers to the “Son of God” and also to the “Son of the Most High.” According to Joseph Fitzmyer, these titles apply “to some human being in the apocalyptic setting of this Palestinian text of the last third of the first century B.C.”7

Obviously the author of John inherited the titles “the Son,” “the Son of God” and “son of the Most High” from Palestinian Judaism. Although this fragmentary text from Qumaran is not explicitly messianic—no messiah is mentioned in any preserved part of it—it does say that “all shall serve him” and this is reminiscent of another text recently made available and known as 4Q521. In that text we are told that the heavens and the earth shall obey (or serve) “his Messiah” (

The “Son of God” text from Qumran (4Q246) speaks of “all who believe” and “all who do evil,” reflecting two distinct poles of humanity. This is anthropological dualism; humanity is divided into two camps: those who believe versus those who do evil.

Other concepts are shared by the Qumran Community (

There are only two main antecedents to Johannine dualism: Qumran and Zurvanism. The latter was developed in ancient Persia by a group within Zoroastrianism. Zurvanism most likely influenced the Qumran sect, and it, in turn, influenced John.11

Returning to John 3:16–21, we are told that all “Sons of Light” will have eternal life, while all those who are not “Sons of Light” will perish. These thoughts are most likely influenced by Qumranic dualism developed at least two centuries earlier. Initiates at Qumran were taught that those who are not Sons of Light will receive “eternal perdition by the fury of God’s vengeful wrath, everlasting terror and endless shame, along with disgrace of annihilation in the fire of murky Hell” (Rule of the Community, 1QS 4.12–13). Similarly the author of John refers to “the wrath of God” (John 3:36), which is reminiscent of the Rule’s reference to “the fury of God’s vengeful wrath” (Rule of the Community, 1QS 4.12). The Qumranites, who regarded themselves as the Sons of Light will, by contrast, be rewarded, “with all everlasting blessings, endless joy in everlasting life, and a crown of glory along with a resplendent attire in eternal light” (Rule of the Community, 1QS 4.7–8). Both John and the Qumran text reflect a common belief in the final judgment at the messianic Endtime.

The fundamental dualism of Qumran theology is seen in the following paradigm of contrasting concepts that come from a single passage (so important that it had to be memorized) in columns 3 and 4 of the Rule of the Community (except for Sons of Darkness which comes from column 1):

| light | darkness |

| Sons of Light | Sons of Darkness [1QS 1.10] |

| Angel of Light | Angel of Darkness |

| Angel of Truth | Spirit of Deceit |

| Sons of Truth | Sons of Deceit |

| Sons of righteousness | Sons of Deceit |

| spring of light | well of darkness |

| walking in the ways of light | walking in the ways of darkness |

| truth | deceit |

| God loves | God hates |

| everlasting life | punishment, then extinction |

Almost all scholars agree that in some way John has been influenced by this dualism and its terminology. Not only in the Rule of the Community but also in John, darkness is contrasted to light, evil to truth, hate to love, and, finally, perishing to receiving eternal life. In fact both the Rule of the Community and John have the key features of the dualistic paradigm.

Nowhere in the ancient world do we find the dualism of light and darkness developed so thoroughly as in the Rule of the Community and the Gospel of John. In both, it is a cosmic and salvific dualism, subsumed under a belief in one and only one God and a conviction that evil and the demons will someday cease to exist. As Raymond Brown observed, “Not only the dualism but also its terminology is shared by John and Qumran.”12

The author of John also refers to the Spirit of Truth (John 14:17, 15:26, 16:13; compare with the variant in John 4:24), another technical term that appears in the Rule of the Community (3.18–19 and 4.21 and 4.23). The mysterious Johannine Paraclete, the Holy Spirit that used to be called the Holy Ghost, is strikingly similar to the Qumran concept of “the Spirit of Truth.” Again, Qumran influence on John seems likely.

All this is not to say that the author of John was a Qumranite or that Qumran theology was Christian. The author of John was a Christian who took some earlier terms and concepts and reshaped them in terms of the contention that Jesus was none other than the promised Messiah to the Jews (see, for example, John 4:25–26). But, of all ancient writings that have survived, only in the Dead Sea Scrolls do we find a type of thought, a developed symbolic language and a dualistic paradigm with technical terms that are so close to the Gospel of John.13 In the words of Moody Smith: “That the Qumran scrolls attest a form of Judaism whose conceptuality and terminology tally in some respects quite closely with the Johannine is a commonly acknowledged fact.”14

The Johannine community had apparently been expelled from the synagogue.15 The term

That John’s Gospel and the Dead Sea Scrolls share certain concepts and terminology is clear. How this influence occurred is less clear. One possibility is that after the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 C.E. (having already destroyed the Qumran settlement in 68 C.E.) the surviving Essenes16 (including those who may have escaped from Qumran) joined a new group within Second Temple Judaism—the Palestinian Jesus Movement. If this occurred, the former Essenes would surely have influenced the members of the new group with their special insights.

Some scholars have suggested that the influx of former Essenes into the Christian community is what is referred to in Acts 6:7: “And the word of God increased; and the number of the disciples in Jerusalem multiplied greatly, and a great crowd of the priests followed in the faith.” The Essenes were of course a priestly group; indeed, they claimed that they, not the priests in Jerusalem, were of true priestly origins. In Acts, this influx of converts occurred before the destruction of the Temple, but Luke, the author of Acts, may have been mistaken chronologically and may have been thinking about the Essenes who joined the Jesus group after 70.

Further support for this contention comes from the fact that Acts refers to the Palestinian Jesus Movement as “the Way.” “Way” is a technical term (see Acts 9:2). Where did this technical term come from? It is not typical of the Old Testament, the Septuagint, the Apocrypha, the Pseudepigrapha, Philo, Josephus or the Jewish magical papyri. It is, in fact, the self-designation of the Qumran sect: “These are the roles of the Way (hdrk)” (the Rule of the Community, 1QS 9.21; cf. 1Q30 2; 1QDM 2.8; 1QS 9.19, 11.11; 1QSa 1.28; 11QT 54.17).

The most likely reconstruction of Christian origins is that members of the Jesus’ group were called “the Way” because of the Qumran sect (or the larger group of Essenes). Some or perhaps many Qumranites or Essenes may have joined the Jesus group by the time Luke wrote Acts.

The most reliable indication that Essenes, and those familiar with Qumran theology, were entering the Jesus group after the 60s is the paucity of parallels in works prior to that time, namely Paul’s letters,17 and—in contrast—the preponderance of parallels to Essene thought in works postdating the 60s and especially 70 C.E., namely Ephesians,18 Hebrews, Matthew,19 Revelation and, especially, John.20

Another route by which the thinking of the Qumran community may have entered or at least influenced the early Christian community is via John the Baptizerd —although this scenario is less likely. Even before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars had concluded that there had been a rift between the Johannine community and the followers of John the Baptizer.21 The first chapter of John’s Gospel contains a polemic against the Baptizer in which the author of John has the Baptizer state: “I am not the Christ;” the Baptizer, according to John’s Gospel, then denies that he is Elijah or “the prophet” (John 1:19–23). The Baptizer’s role is thus very considerably diminished. The author of John probably placed these remarks in the Baptizer’s mouth as a retort to those who believed that the Baptizer was the Christ, or at least Elijah, or the Prophet. The Baptizer’s function in John’s Gospel is reduced to making straight the way of the Lord as Isaiah prophesied (John 1:23) and to proclaiming that Jesus of Nazareth is “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world” (John 1:29). The Baptizer sees and declares that Jesus is “the Son of God” (John 1:34).

The connection between the Baptizer and the Qumran community was so close that a number of scholars have concluded that the Baptizer actually lived at Qumran before taking his message to a wider community.e While it is conceivable that the connection between John the Baptizer and Qumran accounts for the Qumranic influence on the Gospel of John,22 it is much more likely, however, that the influence from Qumran or the Essenes on the Johannine community involved process that continued throughout the period when the Gospel of John took definitive shape.23

The Johannine community seems to have been something like a “school,”24 similar to other schools in antiquity. One of the clearest indications of this is the evidence that the Gospel of John was revised from time to time and whole chapters—chapter 1 and 21 and probably chapters 15–17—were added. To illustrate the reasoning behind this conclusion: Chapter 14 ends with Jesus’ exhortation to his disciples “Rise, let us go from here.” Chapters 15 through 17 consist of long speeches by Jesus appealing for unity. Chapter 18 rather clearly picks up where chapter 14 left off: Chapter 18 begins, “When Jesus had spoken these words, he went forth with his disciples across the Kidron Valley ….” These words follow chapter 14 much better than they do chapters 15 through 17. Chapters 15 through 17 were probably added in a “second edition” of the Gospel.

The theme of John 15–17 is Jesus’ appeal to God that his followers be one. The only document prior to John that stresses this theme, and even applies the term oneness (

In short, the Gospel of John was not written by a philosopher working alone. Written in the late first century—probably utilizing even earlier sources—John’s Gospel is the product of a group of authors, all of whom were probably Jews, who worked independently of the Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke.25 The Gospel of John took shape over more than a decade. Some members of the Johannine school may formerly have been Essenes, some of whom may even have once lived in the caves west of Qumran or on the marl terrace to the south.

While virtually all scholars agree that the author of John was influenced either directly or indirectly by the Dead Sea Scroll sect, there is no consensus on how this influence made its way into the Gospel that bears John’s name. After 30 years of thinking on this issue, I am convinced that the most probable scenario is this: Not all Qumranites died in the Roman attack on their abode in the wilderness in 68 C.E. Some were still alive when the Gospel of John was being written. Some of them, as is now widely acknowledged, no doubt became Christians.26

The most striking and impressive parallels between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the New Testament documents are in those compositions produced by the second generation of “Christians.” Hence, Essene Influence did not come most powerfully with Jesus or even with John the Baptizer, although the points of contact here are also impressive.27 The major influence probably came after 68 C.E., when the Romans destroyed the Qumran settlement.

The Dead Sea Scrolls help us understand how the Johannine community searched for its own identity in a world that had become increasingly hostile. The search for identity had been sought earlier by the followers of the Qumranites’ Righteous Teacher, who led a small band of priests from the Temple in Jerusalem to an abandoned ruin in the wilderness just west of the Dead Sea. Today many discover their own identity by reading the Scrolls, the Gospel of John, and often both. The Dead Sea Scrolls challenge us to think about the source of John’s vocabulary and perspective, and clarify the uniqueness of his gospel and John’s distinct Christology and theology.

This popular article is abbreviated from a larger study to be published in 1994.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Common Era (C.E.) and Before the Common Era (B.C.E.), used by this author, are the alternate designations corresponding to A.D. and B.C. often used in scholarly literature.

P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., “The Mysterious Copper Scroll,” BR 08:04.

See Michael O. Wise and James D. Tabor, “The Messiah at Qumran,” BAR 18:06.

See Otto Betz, “Was John the Baptist an Essene?” BR 06:06.

Endnotes

See the insightful discussion by M. Hengel, “Bishop Lightfoot and the Tübingen School on the Gospel of John and the Second Century,” Durham University Journal (January, 1992) [The Lightfoot Centenary Lectures, ed. J.D.G. Dunn], pp. 23–51, esp. p. 24.

K. Aland dates this papyrus to the beginning of the second century C.E. Aland, “Der Text des Johannesevangeliums im 2. Jahrhundert,” in Studien zum Text und zur Ethik des Neuen Testaments: Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Heinrich Greeven, ed. W. Schrage (BZNW 47; Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1986) pp. 1–10.

See J. Jeremias, The Rediscovery of Bethesda; John 5:2 (New Testament Archaeology Monograph 1; Louisville: Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1966).

J. T. Milik in 3Q15 11.12 reads byt ‘sdtyn and takes the second noun to be a dual, “Bet Esdatain;” the meaning could be “(in) the House of the Two Pools.” See Milik, “Le rouleau de cuivre provenant de la Grotte 3Q (3Q15),” in Les ‘Petites Grottes’ de Qumran, ed. M. Baillet, J. T. Milik, and R. de Vaux (Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 3; Oxford: Clarendon, 1962) pp. 214, 271.

Joseph A. Fitzmyer, A Wandering Aramean, (Society of Biblical Literature [SBL] 25; Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1979), p. 93.

See W. A. Meeks, “The Man from Heaven in Johannine Sectarianism,” Journal of Biblical Literature (1972), pp. 44–72, esp. pp. 70–71.

I use liminality in the sense defined by Victor Turner in Process, Performance, and Pilgrimage (New Delhi: Concept, 1979) esp. pp. 11–59. Also see Jonathan Z. Smith, “Birth Upside Down or Right Side Up?” History of Religions 9 (1969–1970), pp. 281–303, and his “A Place on Which to Stand: Symbols and Social Change,” Worship 44 (1970), pp. 457–474.

For a discussion of this point, see the introduction in J. Charlesworth, ed., John and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Christian Origins Library; New York: Crossroad, 1991), and also see chapter five.

Raymond Brown, The Gospel According to John (Anchor Bible Series; Garden City, NY.: Doubleday, 1966) vol. 1, p. lxii.

Some of the Hermetic tractates and some of the gnostic codices are intermittently similar to John; but then the influence seems to be from John to them.

D. Moody Smith, Johannine Christianity (Columbia, S.C.: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1984), p. 26.

J. L. Martyn, History and Theology in the Fourth Gospel, rev. ed. (Nashville: Abingdon, 1979); R. E. Brown, The Community of the Beloved Disciple (New York: Paulist, 1979).

Despite the cries of a few authors, a consensus still exists among the best Qumran specialists that the Qumranites were Essenes. Lawrence Schiffman challenges the Essene origins of the Qumran group, (see his “The Significance of the Scrolls,” BR 06:05) but he has affirmed (at least to me on several times) that the Qumran group in the first century C.E. is to be identified as Essenes. After almost 30 years of teaching and publishing on the Qumran scrolls I have seen that the Qumran group was a sect (it deliberately removed itself, sociologically and theologically from other Jews) and that we think about Qumran Essenes, Jerusalem Essenes and other groups living on the outskirts of most of the cites, as Philo and Josephus reported.

See Jerome Murphy-O’Connor and James H. Charlesworth, eds., Paul and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Christian Origins Library; New York: Crossroad, 1992), and the pertinent chapters.

K. Stendahl rightly demonstrated that there is a School of Matthew and that the means of interpreting scripture is strikingly like that found in the Qumran commentaries (the Pesharim), see Stendahl, The School of St. Matthew and Its Use of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968). Also see K. Schubert, “The Sermon on the Mount and the Qumran Texts,” in The Scrolls and the New Testament, pp. 118–128; and W. D. Davies, The Setting of the Sermon on the Mount (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966) esp. pp. 208–256. Davies argues—and 1 fully concur—that the Sermon on the Mount “reveals an awareness of the [Dead Sea Scroll] Sect and perhaps a polemic against it.” (p. 235)

See the contributions by Brown, Price, Leaney, Jaubert, Charlesworth, Quispel and Brownlee in Charlesworth, ed., John and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

See W. Baldensperger, Der Prolog des vierten Evangeliums (published in 1898). Also see R. Bultmann, The Gospel of John, trans. G.R. Beasley-Murray (Oxford: Blackwell, 1971) pp. 84–97.

As one of the best commentators on John stated, “There are close contacts between John and Qumran on important points … that there were some associations must be seriously considered, however they were set up.” R. Schnackenburg, The Gospel According to St. John, trans. K. Smyth (New York: Crossroad, 1987), vol. 1, pp. 134–135.

R. A. Culpepper, The Johonnine School (SBL Dissertation Series 26; Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1975). See also G. Strecker, “Die Anfänge der Johanneishchen Schule,” New Testament Studies 32 (1986), pp. 31–47; and E. Ruckstuhl, “Zur Antithese Idiolekt—Soziolekt im johanneischen Schrifttum,” in Jesus im Horizont der Evangelien (Stuttgarter Biblische Aufsatzbande 3; Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Biblework, 1988), pp. 219–64.

Although the author of John may have known one of the Synoptics, especially Mark, he was not dependent on the Synoptics, as Gardner-Smith, Goodenough, Käsemann, Cullmann, Robinson, Smith and other gifted scholars have demonstrated in different ways. As P. Borgen pointed out, John seems to relate to the pre-Synopotic tradition that is evident, for example, in Paul. See P. Borgen, “John and the Synoptics,” in The Interrelations of the Gospels, ed. D. L. Dungan (Leuven: Leuven University Press and Uitgeverij Peeters, 1990), pp. 408–37. See now the major study by D. M. Smith, John Among the Gospels (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992).

It is conceivable that none of the Qumranites ever became Christians. That still leaves most of the Essenes to account for, and if Philo and Josephus can be trusted that means over 3,700 of the 4,000 Essenes living in ancient Palestine.