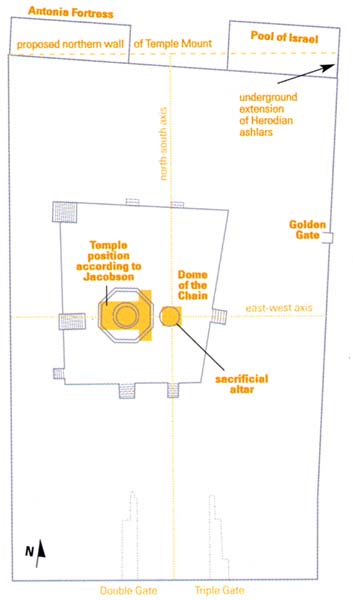

David Jacobson’s theory regarding the shape of Herod’s Temple Mount and the placement of the Temple within it draws heavily on Roman architectural practice. The Romans were particularly fond of symmetrical structures, as Jacobson rightly points out. But he fails to note that this heavy tilt towards symmetry usually occurred when a structure was first being planned. Could Herod have imposed a symmetrical design on his expanded Temple Mount, which was built on the site of Solomon’s Temple? He would have had to take existing features into account. We must also ask why, if the Jewish Temple complex was indeed planned as a newly built Greek or Roman temple, there are so many flaws in the design (see plan). Why are the walls of the Temple Mount not parallel to each other? Why does Jacobson’s “north-south axis” not divide the northern or southern walls into two identical halves? Why is the Antonia Fortress not parallel with Jacobson’s “proposed northern wall of the Temple Mount”?

These flaws show that the Jerusalem sanctuary was not built as a straightforward Roman building. No, Herod’s Temple Mount was rather an asymmetrical complex, made as large as physically possible.

According to Jacobson, “Nothing can be said about the location of Solomon’s Temple (often called the First Temple) based on existing features” (emphasis added) (part one). Jacobson is either unaware of my research on Solomon’s Temple, as he does not mention it, or ignores it because it contradicts his own theory. I have shown the existing archaeological evidence not only for Herod’s Temple Mount, but also for the Hasmonean extension, the original square Temple Mount of Hezekiah and the location of Solomon’s Temple and the Ark of the Covenant.a The research is ongoing, and I hope soon to publish in BAR the results of a photogrammetric survey of es-Sakhra (the rocky summit of Mount Moriah, enshrined within the Dome of the Rock) that both confirms and throws fuller light on my earlier discoveries.

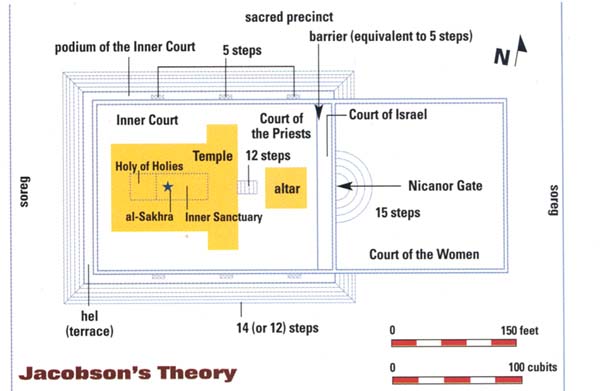

The starting point of my research was the discovery of archaeological evidence for the 500-cubit-square Temple Mount.1 However, Jacobson writes, “According to ancient descriptions of Herod’s Temple, the sacred inner precinct (with the altar at its center) was between 400 and 500 cubits square” (part two, p. 56). There is no ancient source which says that the altar stood in the center of a square, and nowhere does it say that the dimensions were “between 400 and 500 cubits.” The Mishnah (the earliest rabbinic codification of the law, from about 200 A.D.) clearly states that the Temple Mount was 500 by 500 cubits, nothing more and nothing less (Middot 2.1). Of course, Josephus mentions a stadium, but his measurements are not always reliable, as they apparently are only rough estimates. For example, Josephus writes that the altar of the Temple measured 50 cubits square,2 but Mishnah tractate Middot 3.1 says that it was 32 cubits square. Josephus is clearly wrong, as there was no room for such a large altar.3 My research has shown unequivocally that the measurements in Middot are correct. Middot 2.1 also says that the spaces around the Temple court were unequal, which directly contradicts Jacobson’s symmetrical layout. According to Middot, the southern court was largest, with the other courts diminishing in size going counterclockwise.

Josephus makes clear that Herod was not free to do what he liked, but was under the constraints of Biblical injunctions and Jewish tradition. For example, the fact that the lintel of the portico was made of five wooden beams, a very un-Roman-like construction, indicates that one cannot treat the Temple Mount as merely another Roman or Greek sanctuary.

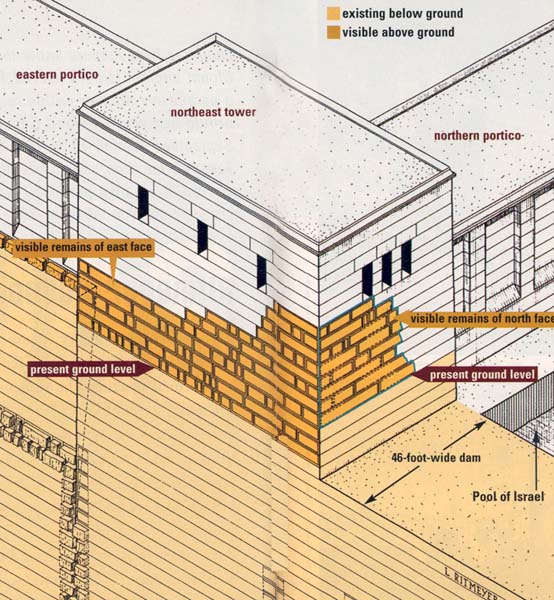

Let us now look at some of the archaeological details of the Temple Mount, starting with the northern wall, which Jacobson wants to move further to the north in order to accommodate his symmetrical design. Is this possible? Certainly not—though few realize it, the Herodian northeastern corner and part of the northern wall still stand along the present-day Temple Mount!

In fact, all four corners of the Herodian Temple Mount have survived the Roman destruction to a considerable height. This is because the corners were made of very large stones, some of them 40 feet long! Even the Romans were unable to shift these giant blocks. The northeast corner of the Herodian Temple Mount is no exception.4 It is still visible at the northeastern corner of the Temple Mount as it appears today.

This tower and the stretch of wall between it and the Golden Gate are the least understood part of the Temple Mount, not only by Jacobson. Very little has been written about it, and several scholars have followed Claude Conder5 in identifying this section as post-Herodian.6 In fact, large parts of Herod’s corner tower and its eastern and northern faces are in situ (see drawing at right). The typical Herodian margins and bosses are clearly visible on most of these huge stones, which are, on average, nearly 4 feet high, the same size as all the Herodian stones in the other retaining walls of the Temple Mount. The eastern face of this tower is easily seen. I wrote about this northern part of the eastern wall and illustrated the remains in a previous BAR article.b The eastern face of this tower has a typical header-and-stretcher construction at both its corners. The Herodian northeast corner today stands above ground to a height of 11 courses and below ground for another 19, for a combined height of 30 (!) Herodian courses.

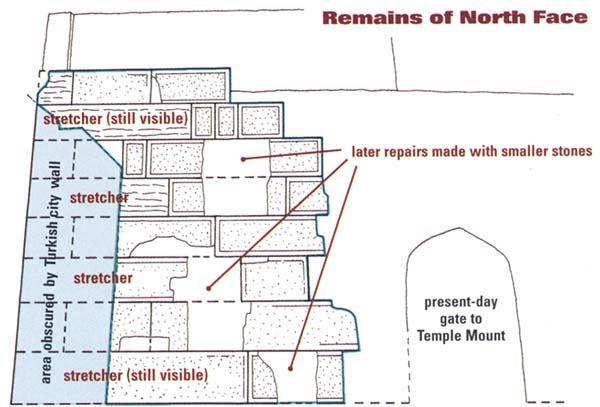

I believe that part of the northern face also still exists.

This face, which is part of the Herodian northern wall of the Temple Mount, is little known and hardly visible because of trees recently planted in front of it. The 16th-century Turkish city wall also abuts this corner and partially obscures it (as shown in the drawing). The northern face can be seen in a photograph that I took many years ago, before the trees were planted. Many of the damaged faces of the Herodian ashlars have been repaired with much smaller stones, leaving a patchwork that an untrained eye can hardly recognize as the northern facade of the Temple Mount.

If you look at the drawing of the same area, you will see that two large stretcher stones (placed with their long sides visible) are still in place, one at the bottom of the large masonry and the other at the second course from the top. In between these two long stones, there are two others in the alternating courses (on the left in the drawing, near the Turkish city wall) that must also be long stretcher stones. Since the joints between the courses of the northern face of this tower line up with those of the eastern face, it is clear that these large stones are part of a typical Herodian header-and-stretcher corner construction. This corner also forms a 90 degree angle and is in line with the southern front of the Antonia Fortress. We have here a very clearly defined straight course for the northern wall of the Temple Mount. How is it then possible to suggest that the northern wall was somewhere else?

The bold statement by Jacobson that the Herodian stones in the northern face of the northeast tower must be in secondary use because stones from later periods are interspersed between them doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. My photograph clearly shows that in the lower four courses small stones have been used to repair only the damaged parts of the Herodian ashlars. The greater part of the Herodian ashlars still exists behind these repairs.

Jacobson, like some other scholars, argues that the absence of pilasters at this corner of the Temple Mount shows that it is post-Herodian. He is wrong on two counts. First, for aesthetic reasons, pilasters do not continue right up to the corner. Corners are often treated differently to give an impression of strength. This can be seen, for example, in the photograph of the Tomb of the Patriarchs (top). The corners have been treated to make them look like towers, just as in the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

Second, the northeast tower, together with the Antonia Fortress, had a defensive function, as attacks could be expected from the relatively flat land to the north. Pilasters would weaken a tower, because the wall between the pilasters is always very thin.

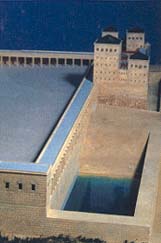

As Jacobson mentions, the eastern wall of the Temple Mount continues below ground beyond the northeast corner. However, although the Herodian ashlars continue without a break, their character changes: The width of the wall in this section is far greater than the usual 15 feet. Here the wall is 46 feet wide! The only explanation for this is that this part of the wall served as the eastern dam of the large water reservoir called the Pool of Israel. This pool, which was built as an integral part of the Herodian Temple Mount, was strategically placed just outside the northeastern corner of the Mount as a kind of moat in what is now known as St. Anne’s Valley, protecting the northern wall of the Temple Mount as well as providing an abundant water supply.

A rare photograph taken in 1894 shows the Pool of Israel before it was filled in with earth.7 The 19th-century British explorer Charles Warren investigated the bottom of the pool and found a plastered floor 75 feet below the level of the Temple courts. The pool is so deep that the bottom cannot be seen in the photograph. Four large windows are visible in the northern wall of the Temple Mount. The large stones below these windows belong to the southern wall of the Pool of Israel, which corresponds to the northern wall of Herod’s Temple Mount.8

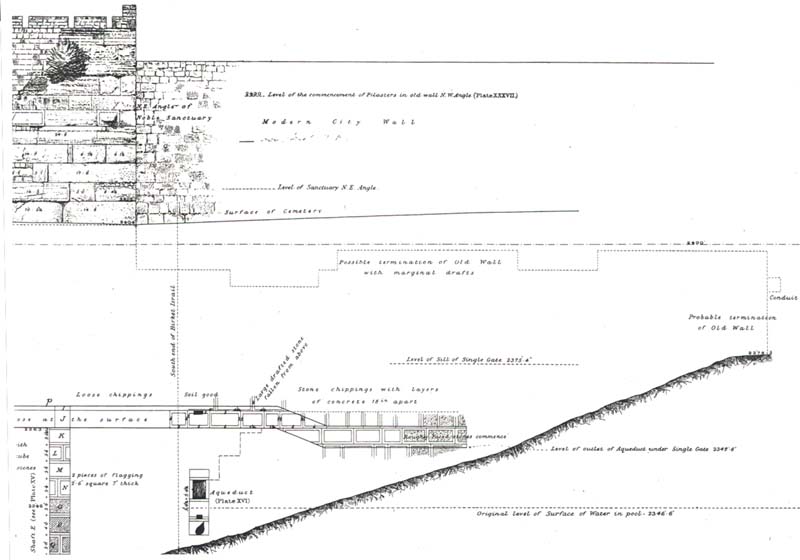

Jacobson states that his northern wall joins the eastern wall “close to the point where Warren found it ended underground. Warren labeled the vicinity of this spot on his drawing of the elevation of the east wall as the ‘possible termination of Old Wall with marginal drafts.’” I have an original copy of Warren’s drawing, and this spot (near the center of the drawing) is not at all where Jacobson indicates it on his plan (part one, p. 53). Examining the drawing, it is clear that at this point Warren is referring to the preserved top of this wall and not to its northern end, which is 125 feet north of the northeast corner of the present-day Temple Mount! It was at that point on his drawing (at far right) that Warren drew a vertical line from the preserved top of the wall down to bedrock and labeled it “probable termination of Old Wall.” Jacobson’s “northeast corner” is only half the true distance of the northern extension of the eastern wall indicated by Warren! This is misleading in the extreme. This northern extension goes beyond the northeastern corner of the Temple Mount to the northeastern corner of the Pool of Israel.

It is not surprising to see that Jacobson’s ideas about es-Sakhra also are not fully researched. He claims in his article (part two) that “the rock has been cut down by at least 5 feet,” without referring to my research, which has identified the imprint of the southern wall of the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple and the western and northern rock scarps as indicating the line of the corresponding walls. He makes no attempt at understanding this most evocative and telling of ancient remains.

Jacobson also makes statements that are only partially correct. In his article (part two), he says that “according to both the Mishnah and Josephus, three sets of steps led up to the level of the Temple.” He then says, “Both sources then agree that there were 5 steps from the hel to the Court of the Priests.” This is not true! Middot 2.6 refers to four steps (one of which was one cubit high, while the others were half a cubit high) at what Jacobson calls the “barrier,” which led up from the lower Court of Israel to the Court of the Priests (see Jacobson’s plan, below). These were located in the east and are not mentioned in connection with the hel, which, even according to Jacobson’s plan, is located on the south, west and north only. Middot does not mention the sets of five steps at the gates that Josephus refers to, while Josephus is silent about this “barrier.”

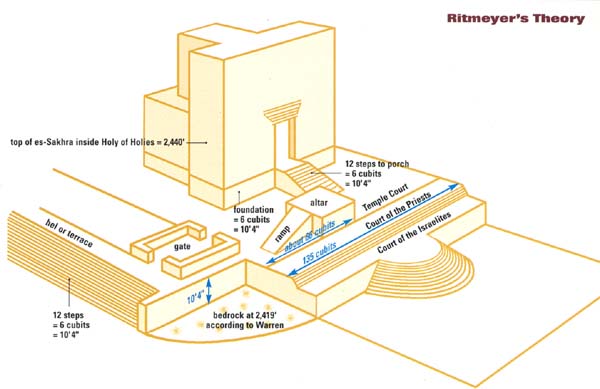

Jacobson’s calculation (part two) of 14+5+12=31 steps (14 steps up to the hel, 5 for the barrier and 12 steps to the Temple, each half a cubit high) for a total of 15.5 cubits (just over 26 feet) is quite wrong and cannot be used to say that 5 feet are missing from es-Sakhra. According to Middot, there were only two sets of 12 steps: one leading up to the hel (there may have been 14 at the western end, where the ground level is lower) and the other to the portico of the Temple, with a combined height of 12 cubits (half a cubit per step). This equals 20.6 feet. The difference between the ground and the top of es-Sakhra is exactly 21 feet (the top of es-Sakhra is 2,440 feet above sea level, and the ground at the foot of the lower steps is 2,419 feet above sea level). The difference of a few inches is accounted for by the statement in the Mishnah that es-Sakhra stood slightly higher than the floor of the Temple. Mishnah tractate Yoma 5.2 speaks of the Even ha-Shetiyah in the Holy of Holies, which “was higher than the ground by three fingerbreadths.” The term Even ha-Shetiyah simply means Foundation Stone, indicating that es-Sakhra was the foundation for the Holy of Holies. This is very strong proof for my analysis of es-Sakhra and shows that Jacobson is wrong when he claims that 5 feet are missing from the top of es-Sakhra.9

Turning now to the altar: As already mentioned, there is no historical source that says that the altar stood in the center of the Temple Mount. Nevertheless, that is where Jacobson puts it to fit in with his geometrical design of the Mount. He then places the Temple to the west of the altar, on the same east-west axis. Jacobson also believes that there is a relationship between the size of the altar and the Muslim Dome of the Chain, and also between the Dome of the Rock and the Temple: “Thus, we see the following pattern emerging, with the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain … reproducing the Temple and altar in size and respective locations” (part one). This pattern, however, does not agree with the detailed account of the Temple and altar locations according to Middot.

Middot 5.1, 2 states that the Temple court, that is, the space where the Temple building and the altar were located, was 187 cubits (322 feet, 98.18 meters) from east to west and 135 cubits (232.5 feet, 70.88 meters) from south to north. The south-to-north distance of 135 cubits was divided as follows:

| 1. The ramp | 30 cubits |

| 2. The base of the altar | 32 cubits |

| 3. The space between altar and rings | 8 cubits |

| 4. The area of the rings | 24 cubits |

| 5. The space between the rings and the tables | 4 cubits |

| 6. The space between the tables and the small pillars | 4 cubits |

| 7. The space to the north of the small pillars | 8 cubits |

| 8. The remainder (between the ramp, the wall and the place of the small pillars) | 25 cubits |

| Total | 135 cubits |

When one transfers these distances to a plan, it becomes clear that the Temple and the altar did not stand on the same axis. Instead, the altar stood to the south of the longitudinal Temple axis (see drawing, below). Jacobson should either shift the Temple to the north or the altar to the south, but that, of course, does not fit in with his geometry.

I will conclude by considering the steps that appear in 19th-century photos and on Warren’s plans and the bedrock ridge photographed by Hershel Shanks (part two). These are very interesting. Without having seen them, I had already drawn the southern soreg line in exactly this position.10 The soreg, however, was a boundary wall and not a staircase. The steps mentioned by Josephus are the ones leading up to the hel, or terrace, and are not connected with the soreg. Jacobson may be right that this is part of a crepidoma, the stepped base of a Greek or Roman temple, but I suggest it may be that of the later, Roman temple built by Hadrian, as the historical sources regarding the Jewish Temple mention no steps at this location.

One cannot impose preconceived ideas based on single-phase buildings such as the Tomb of the Patriarchs on a multiphase site such as the Temple Mount. And as excavation on the Temple Mount is out of the question, one must rely on spadework of a different kind. There is no way to find the location of the Temple other than by determining the various stages of the Temple Mount’s development through analysis of the remains, both visible and camouflaged, illuminated by the written sources. In my 26 years of Temple Mount research, I have worked my way in from the Herodian outer frame to the 500-cubit-square Temple Mount, attested to by one of the most reliable Jewish sources, to the heart of the matter, the Temple itself. David Jacobson’s theory, on the other hand, rests on a frame created out of a misreading of Charles Warren’s plans and, alas, on flawed—not sacred—geometry.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Kathleen Ritmdeyer and Leen Ritmeyer, “Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount,” BAR 15:06; L. Ritmeyer, “Locating the Original Temple Mount,” BAR 18:02; “The Ark of the Covenant: Where It Stood in Solomon’s Temple,” BAR 22:01. All three articles have been published as a book: L. Ritmeyer and K. Ritmeyer, Secrets of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1998).

Leen Ritmeyer, “Locating the Original Temple Mount,” BAR 18:02, pp. 40–42.

Endnotes

Leen Ritmeyer, “The Architectural Development of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem” (Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. of Manchester, 1992).

See Ritmeyer, The Temple and the Rock (Harrogate, UK: Ritmeyer Archaeological Design, 1996), p. 51 note 45.

For reports on the excavations at the northeast angle, see Charles Warren and Claude R. Conder, Survey of Western Palestine, vol. 2, (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1884), pp. 126–147; Charles Wilson, “The Masonry of the Haram Wall,” in Palestine Exploration Fund, Quarterly Statement (1880), pp. 39–46; Wilson and Warren, Recovery of Jerusalem (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1871), pp. 159–188.

Frederick J. Hollis, The Archaeology of Herod’s Temple (London: Dent and Sons, 1934), pp. 50, 58; Joannes Simons, Jerusalem in the Old Testament (Leiden, 1952), pp. 417ff., 500, note 2.

Original photograph on glass plate by R. E. M. Bain, published in John H. Vincent, Early Footsteps of the Man of Galilee (New York: N.D. Thompson, 1894), p. 129.

At first it would appear that two different kinds of stones were used in this wall, separated by the line of vegetation. The stones above this line are rough and the ones below, at lower right of the picture, are smoother. Thick walls like this one, however, were built by placing two rows of stones with their faces outward and filling the space between with rubble and mortar. Only the face of the stones was dressed and never the back, because the back would not have been seen and the rougher surface provides a better grip for the mortar. The rough upper stones, then, are actually the back of the stones that face southward towards the Temple Mount. The vegetation grows in the core of the wall, and below that are the smoother stones that face the pool. The original plaster, which would have been attached to this wall, has not survived.

I could play devil’s advocate and suggest that from the east there were 15+4+12 steps, which still would make a difference of 16 cubits. Many researchers have fallen into this trap. Although this may be surprising at first, it is nevertheless in agreement with the writings of Josephus, where we read that the 15 steps in the Court of the Women were shallower than all the others (Jewish War 5.206). In contrast to the other steps of the Temple court, which had a height of half a cubit (Middot 2.3), Middot is silent about the height of the 15 steps. It states only that they are “corresponding to the fifteen Songs of Ascents in the Psalms, and upon them the Levites used to sing. They were not four-square, but rounded like the half of a round threshing-floor” (Middot 2.5).

Starting at the top, the 12 steps leading to the Temple porch are 6 cubits high and the barrier 2.5 cubits. This makes 8.5 cubits, or 16 feet 8 inches, leaving 6 feet 4 inches for the 15 semicircular steps, giving a height of just over 5 inches to a step, which is in harmony with the observations of Josephus. The height of these steps also comes close to that of the usual Herodian steps, many of which were found in Benjamin Mazar’s excavations.