Sister Wendy’s Top Twenty Biblical Paintings

015

To help us celebrate 20 years of BR, we asked the famous, beloved nun and art critic Sister Wendy to write about 20 of her favorite biblical (or Bible-inspired) paintings that have appeared in our pages over the years. Enjoy!—Eds.

Biblical scholars may raise a pitying eyebrow, but I love BR almost as much for its illustrations as for its texts. Few art magazines can equal the range and beauty of the reproductions that enrich our understanding of BR’s articles: The Word is communicated not only verbally but visually. In selecting my favorite images, it has been extremely difficult to narrow myself down to a sparse 20!

016

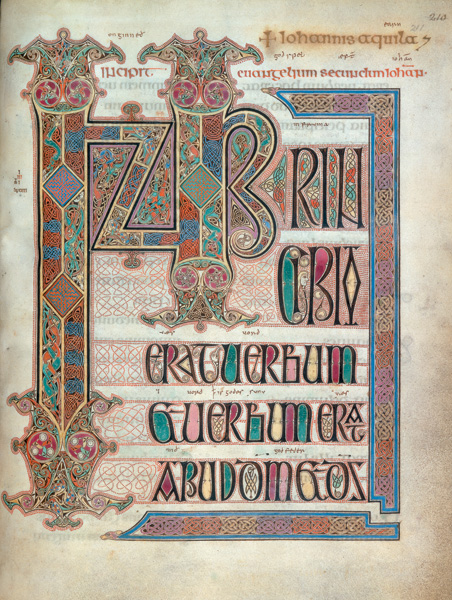

In Principio Erat Verbum (“In the beginning was the Word”)

c. 700, from the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, London)

This wonderful work of religious art, the opening page of the Gospel of John in the Lindisfarne Gospels, is not so much a biblical illustration as the Bible itself (even if only the New Testament) revealed as Word—Word so beautiful that all the resources of human genius must offer themselves to render it worthily. The unknown Northumbrian monk who produced this book has an amazing control of his reed pen, an awareness of color, a supreme sense of geometry and design; at every point, yet never with overcrowding, the eye is entranced by the subtlety of his intricacies. Living creatures hide amongst the patternings. We can make out birds, beasts (real and imagined), the human head. All are gloriously subsumed in an act of creative homage to the sacred Scriptures.

017

The Penitent St. Jerome

c. 1513–1515, by Lorenzo Lotto (National Museum of Art, Bucharest, Romania)

Although this work is not precisely a biblical illustration, it does illustrate with moving power the significance of the great biblical translator, St. Jerome. He seems to have been a man of uncertain temper, which may well and fittingly explain why he is so often portrayed, as here, in an attitude of repentance; but he was acclaimed as a saint and imagined as a cardinal, simply because of his burning zeal for the Bible. Lotto sees him as resting on his cardinal’s scarlet, one arm propped on his Bible and holding the crucifix, while with the other he prepares to chastise himself. He is in a singularly awkward position, alone and naked, stiff with tension. His love for the Word of God makes all this trivial to him. That same holy Word will transform the grumpy intellectual into a saint.

020

The Census at Bethlehem

1566, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (Musée d’Art Ancien, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels)

I particularly love this pre-Nativity painting by Brueghel. The artist shows us a busy Flemish village. It is bitterly cold. The dim red sun of winter is literally about to sink. Crowds of strangers have arrived for the census, while all around the usual activities move busily along—work and play in equal measures. Wholly unobserved, as would indeed have been true, a tired and visibly pregnant young woman holds herself erect on her donkey (a weary donkey plodding hopefully on) while her husband heads almost blindly towards the inn. It is always a surprise, suddenly seeing the holy family inconspicuous in the crowd, and realizing that God is always there, if only we are alert enough to see Him.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf

1634, by Nicholas Poussin (National Gallery, London)

Of all the artists, great and small, who have been inspired by the Scriptures, it seems to me that Poussin is the most naturally attuned to the sacred. His unique blend of intellectual rigor and pure poetry means that he can show us, as can none other, the drama of this scene and its tragedy. While Aaron (center right) lords it with hieratic power, completely subjugating the Israelites emotionally, the people glory in the newfound accessibility of their god—their possession, theirs to manipulate (the secret desire of human beings from the beginning). The true prophet, Moses (upper left), clambers stiffly down from the mountain where he has encountered the true God and received His demands, and in the darkness of dismay, shatters the stone of the Commandments. Only a few of these faithless revelers have as yet seen Moses: Poussin conveys a frightening sense of what is to come.

021

Othyoth (“Letters”)

1992, by Samuel Bak (The Pucker Gallery, Boston)

Bak was born in 1933 in Vilna, Lithuania, into a thriving community of over 80,000 Jews, of whom barely 200—Bak and his mother among them—survived the Holocaust. The greatness of his art springs from an ever-constant sense of human folly and human cruelty. Here he paints the stone tables of the Covenant, splitting from within under some unbearable constraint. The letters literally implode and vaporize, as God’s will for us is smashed out of its written form. This is not how the story is told in Exodus: Bak is painting a midrash, a commentary by the rabbis, that imagined the very letters of the words disappearing, to show the distress felt even by stone for human faithlessness. It is a desolate picture. We can only take comfort from seeing, with Bak, a stony world that yet contains enough slabs on which our gracious God may write His will again.

022

The Creation and the Fall

1445, by Giovanni di Paolo (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

How the world was created and how humankind fell and lost its natural happiness are mysteries so deep that the Bible can only speak of them in poetry. Di Paolo seems to me to rise to that poetry, not to its sublimity but to its truth. On the left we see God, His finger calling into being the various layers of our world. Seraphim surround Him. He floats down from the golden spacelessness that is eternity. On the right, Adam and Eve, sullenly and not by their own volition, are leaving Paradise. An angel with wings of fire pushes them gently over the flowers and grasses, under the gleaming Edenic trees, out into the sorrows that come with disobedience. The angel grieves for us, and the face of God shows a sorrowful disappointment.

David Playing the Harp Before Saul

1657, by Rembrandt van Rijn (Mauritshuis, the Hague, the Netherlands)

This is a detail of a much larger painting, where we can also see the moody Saul, perhaps already insane with jealousy of the young hero David (shown), who seems to be superseding him in popular esteem. David is aware of this. Rembrandt will not idealize him. Here is no handsome adolescent, but a plain-faced lad. Dark and sensitive, he tries to lose himself in his beloved music, to let the harp rescue him from what must have become an intolerable situation. Art can be a means of prayer, and music too—both listening and playing. David does both, reaching out silently to God while his fingers speak for him. This is the longing David of the Psalms, not the warrior, and Rembrandt, with his own longings, can paint him almost as a self-portrait.

025

The Temptation of Christ

early 16th century, by Joachim Patinir (Upton House, Bearsted Collection, Banbury, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom)

Jesus and temptation is an almost bewildering concept, and Patinir grasps its enigmatic strangeness. He is a painter of the bird’s-eye view, always gazing down from an impossible height. Here Jesus, too, is at an impossible height—“a very high mountain,” says Matthew (4:8)—and the devil, loathsome in a monk’s habit through which the fires of Hell are glowing, offers him the immensity of the world. Patinir does not paint much of its kingdoms, although there is the odd building here and there, but we clearly see its vastness and its beauty. Jesus is all rejection. He will indeed gain this forbidding world, but the somber hues of his robe suggest to us that it will be by dying.

Samson in Gaza

1912, by Lovis Corinth (Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin)

Lovis Corinth, who was born in 1858, was a German Impressionist until he was struck down by a severe stroke, just one year before he painted Samson, blinded and imprisoned. He so had to force his hands into motion that the feathery stroke of his earlier style was made impossible. Like Samson, Corinth felt like a man deprived of liberty, helpless and enraged. He painted this picture from the heart: It is an agonized image of vulnerability, of loss of freedom, of lonely pain. Samson’s body is still massive, just as Corinth still had his painterly skill, but neither the biblical judge nor the artist was free to use his powers. The hands, tautly outspread, the straining eyes, the blood that spells disaster: All are Corinth’s own, transferred to Samson and shared with us. Both men cry silently for redemption.

026

Esther Before Ahasuerus

c. 1500, by Filippino Lippi (Musée Condé, Chantilly, Paris)

The Book of Esther is one of the Bible’s great stories, almost a novel. Filippino Lippi sees primarily the story, rather than its mystical meaning. He knows, of course, that it is Esther’s fate to risk all to save her people, but there is little hint of it in this delightful procession of beauties. They have been summoned to fill a space in the royal harem, and the king’s favor falls upon the gracious figure of Esther (foreground, center), lovely and appealing in her scarlet robes. She gently bows to his will while the other ladies pass unnoticed. If we examine the picture, we could deduce that the distance between the king’s throne and the floor of the hall, its height, its semi-barred recession, all make it clear that Esther’s position, even as queen, is essentially inferior. The massive pillars of the establishment make it eminently clear that she would transgress these barriers at her peril, yet Filippino does not portray a heroine.

027

Queen Esther

15th century, by Andrea Castagno (Uffizi, Florence)

For Andrea Castagno, unlike Filippino Lippi above, to be a heroine is of Esther’s essence; to him the queen’s beauty is only incidental. He shows us a levelheaded woman of valor, with clear and dispassionate gaze, assessing what course needs to be taken if she is to save her people from destruction. Obedience to the king’s command imposes a role of inactivity. But Esther is the perfect model for the loyal opposition who can urge authority into questioning its own wisdom. She tucks her thumb in her sash with almost masculine jauntiness, lifts her fine head, and prepares to do or die. Her cloak may be brocade and her headscarf silk, a large jewel may gleam at her breast, but in all that matters, she is stripped for action, far more bare to her fate than any literal nakedness could make her.

The Agony in the Garden

late 18th century, by Francesco de Goya (The Louvre, Paris)

The Gospels insist we should understand that Jesus was “a man like us in all things, sin alone excepted” (Hebrews 4:15). The Agony in the Garden is the great proof of this, and in times of suffering, above all, we cling to this image of Jesus, approaching with great fear the first stages of his death. Goya, who lived at a time of terrible misery—to which he was temperamentally drawn—sees Jesus as almost evanescent with distress. He glimmers in the nighttime scene, alone on his rocky eminence except for the faint presence of the angel holding out a chalice, and a sleeping dog. This is the cup of death that Jesus dreads, but as it is the will of his loving Father, he stretches out his arms. This was not how Goya had seen people die—the upright savior, ravaged by fear, lights up the world with an image of pure love.

028

The Annunciation

c. 1450, by Filippo Lippi (National Gallery, London)

There are countless imaginings of the Annunciation, all different, all focused on two figures, Mary and the angel Gabriel. In some we see the Father leaning down from heaven and the Spirit like a dove speeding in beams of light. Filippo Lippi uses this imagery but in the most discreet manner. Only the hand of the Father is seen, unobtrusively, and the Spirit hovers quietly and indistinctly before an almost imperceptible slit in Mary’s gown. All our attention is drawn to the beautiful angel, youthful and self-contained, and the equally beautiful virgin, who has already said her fiat and is not self-contained but God-containing. She is lost in the wonder of her vocation, totally receptive. Even the hangings on her chair seem prepared to embrace the child whose unseen presence already fills the scene with light.

Noli Me Tangere

c. 1550, by Titian (National Gallery, London)

There are many paintings of the Crucifixion, few of the Resurrection. This central mystery of the Christian faith escapes our imagining. What did Jesus look like, having passed through death and emerging victorious? Since Mary Magdalene, here on her knees before Him, took him at first to be the gardener (and Jesus carries a simple sickle), it is obvious that He was not still clad in his shroud, as Titian depicts him. This is a hint not to take the event too literally but to see it as it is, holy poetry. Where Jesus stands, the world is springing into lovely flower; where the Magdalene kneels, all is still barren. Behind Jesus, sheep and tranquility; behind her, the solid signs of a fortified and material way of living. Although he tells her gently not to “hold” him, he has appeared in the garden solely for her joy. Titian shows a radiance slowly dawning as the Magdalene begins to understand that life is now eternally changed.

030

John on Patmos

early 15th century, from Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry by the Limbourg Brothers (Musée Condé, Chantilly, Paris)

St. John is often portrayed in illuminated manuscripts (as are the other evangelists) preparing to write his gospel. Here the greatest of illuminators, Jean, Paul and Herman Limbourg, show him struggling to write (as its presumed author) the Book of Revelation. His emblematic eagle holds his writing equipment, the isle of Patmos being too small even for a bookrest, and the saint gazes in a startled and prayerful awe at the mysterious visions that force themselves upon him. The Limbourgs show us a lonely world of night and water. The boat that has brought John to this solitary place withdraws to the fortified towers of common humankind. Abandoned, and content to be so, the visionary looks up to receive the weight of divine revelation.

031

The Suicide of Saul

1562, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

David’s rise demands the fall of Saul, yet there are biblical hints that Saul, too, had periods of true greatness. This astonishing picture shows him with his sons, coming to the rescue of the town of Jabesh-Gilead (background) and raising their siege, only to fall later on the slopes of Mt. Gilboa (foreground). At the bottom left, we see the men of the rescued town taking great risks to retrieve Saul’s body for burial. But what Brueghel so overwhelmingly conveys is the clash of armies, the weight and savagery of the forces bearing down on Israel, and how all this hideous ferocity is contained within a small cup in the world’s great surface. War is both terrible and ultimately unimportant.

033

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery

1917, by Max Beckmann (The Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, Missouri)

The horrors of the First World War were too much for Beckmann: He broke down and was invalided out of the army. During these traumatic months, as he struggled back to mental health (the war was far from over when he painted this scene from the Gospel of John), images of human cruelty and suffering haunted him. He has Jesus and the woman hemmed in by violence and hatred, sheer extrapolations into the gospel story, but it is noticeable that only the man removed from them, on the far side of the fence (the noncombatant who urges bloodshed) has his eyes open. Jesus and the woman have their eyes closed, and so does their most vicious tormentor, the sneering butcher whose hands form a square with those of the praying woman and the quiet, forgiving Lord. The ravaged face of this Lord Jesus is that of Beckmann himself, passionately seeking the role of reconciliation and healing.

Jonah and the Whale

1988, by Albert Herbert (England & Co. Gallery, London)

Albert Herbert taught in a prestigious London art school where most of his peers were painting abstracts. It was with dismay and reluctance that he discovered he was himself a naturally religious man whose personal desires expressed themselves spontaneously in biblical imagery. These works forced themselves into being. Always they are unique, Herbert’s own take on what may be a familiar scene. Here, though woman and bird—the peace of domestic life—await him on the shore, Jonah seems strangely reluctant to leave the safe haven of the whale’s belly. The biblical Book of Jonah has him swallowed up as part of the divine rebuke for his disobedience, but in that dark cavern Jonah has obviously been content. The demands of the normal world do not seem to appeal, and he stands there naked, uneasy, but upright. Soon he will take a header into those roiling waters and glumly bend his head to his vocation.

035

The Last Judgment

1445–1448, by Rogier van der Weyden (Hotel-Dieu, Beaune, France)

Van der Weyden painted this great altarpiece for a medieval hospital—a haven where, for the most part, people went to die. “After death, the judgment” (Hebrews 9:27). His intention was not to frighten but to console. Below the angel Michael, at the lower right, the damned scurry wretchedly to Hell, but no devils drive them there: They drag themselves and each other. Grace is offered, the artist implies, and we are free. Here, luminous and compassionate, Michael holds the scales. The souls rising from their graves are shown at either side, in prayer (left) and in astonished recognition (right). In the scales, two men, identical—they had the same chances—react differently, with one soberly thankful and the other overcome with horrified remorse. Around Michael, angels summon the dead to what should be a great moment of gratitude to God, but only if they ask his forgiveness while there is yet time.

Ruth in the Field of Boaz

c. 1637, by Nicholas Poussin (The Louvre, Paris)

When the supplicant Ruth (kneeling) encounters Boaz, the stage seems set for nothing more than a man-woman relationship. Only an artist of the most profound sensibility can visualize this scene in its spiritual dimension, and make us understand what it means. These are the ancestors of Christ that Poussin is painting, and from Ruth’s devotion and submission to her mother-in-law, and from Boaz’s kindness and desire to be a good Israelite, will flow consequences for the future. Poussin seems to show us this world of ours, its vastness, its beauty, its fertility. Men and women labor, but beyond them great buildings arise, rivers and seas lie under the dark evening clouds, mountains bar a view to the distance. Ruth kneels in the shadow of a spreading tree, amidst images of fruitfulness, and both she and Boaz make gestures of acceptance. They accept far more than they can consciously understand: an image of all human activity.

To help us celebrate 20 years of BR, we asked the famous, beloved nun and art critic Sister Wendy to write about 20 of her favorite biblical (or Bible-inspired) paintings that have appeared in our pages over the years. Enjoy!—Eds. Biblical scholars may raise a pitying eyebrow, but I love BR almost as much for its illustrations as for its texts. Few art magazines can equal the range and beauty of the reproductions that enrich our understanding of BR’s articles: The Word is communicated not only verbally but visually. In selecting my favorite images, it has been extremely difficult […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username